The Inheritance (1970) is a black and white film, fundamentally composed of close-ups and guitar chords. By way of a farcical western, Ozualdo Candeias turns Hamlet into a parable, takes Shakespeare for his ambition to achieve a tragic universality that encompasses the level of his experimentalism, a counterpoint to his radical specificity. Hamlet is adapted as a narrative premise to the vernacular invention that runs through the creation of any image that is under the realm of its director.

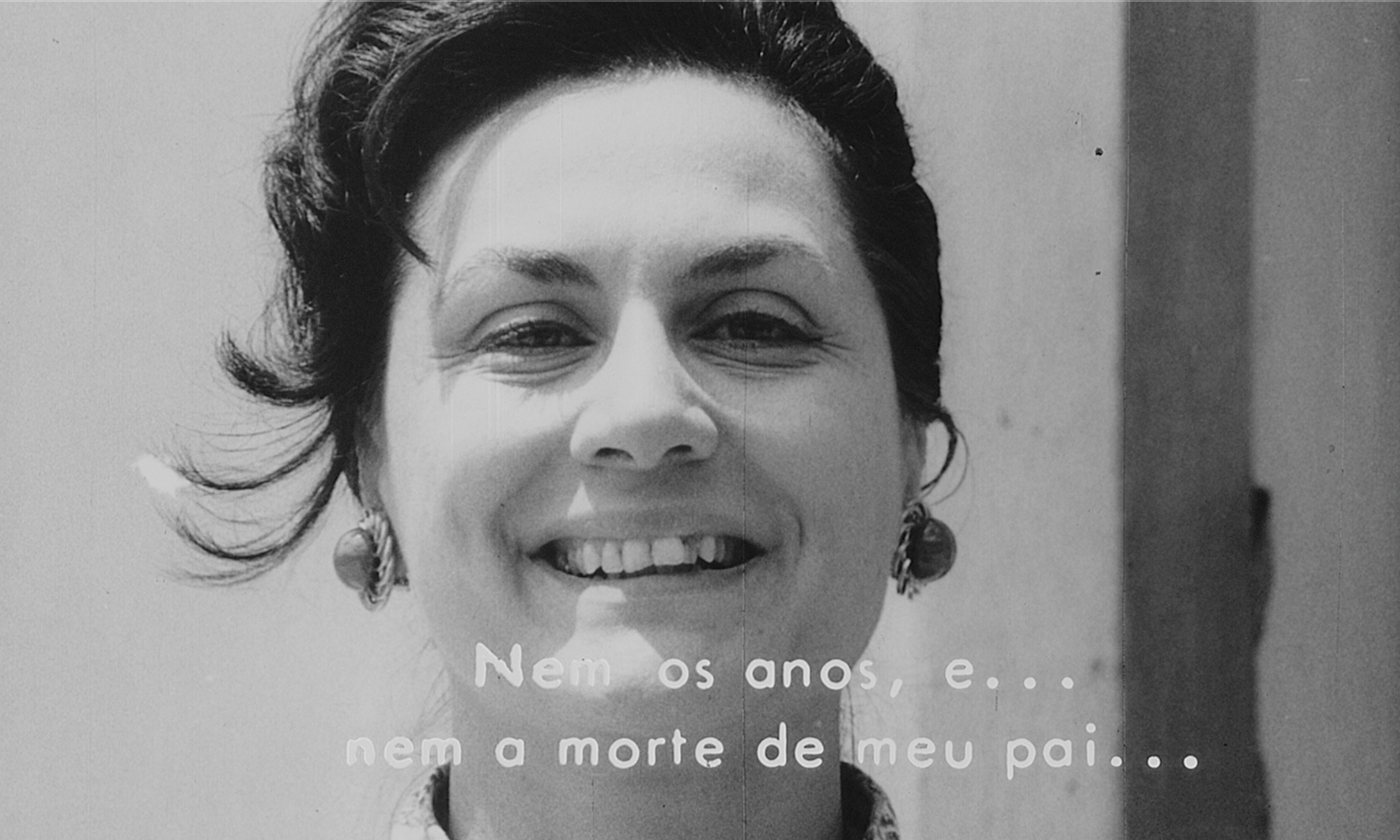

David Cardoso, a variably Shakespearean actor, is the Hamlet that takes up much of the screen time. Starring in a film with no recorded dialogue, with text that cuts through the images as part of their flow of movement, the dramaturgy of Cardoso's performance and that of his fellow actors is conceived exclusively as expression. This causes some important things to happen: First, there is a redoubling of the weight of each face that enters the frame. Second, the order of their expressions becomes an embodiment of the environment where the film is set, that is, it deepens the significance of the location in a gesture that goes beyond the geographical dispersion continuously proposed by Candeias throughout his career. Candeias' choice to film places never touched by the interest of previous filmmakers always ends up as a formal proposition, as a treatment of the location that seeks the camera as an engine of invention integrated to actors that enable the material influences of the land where it is filmed.\

In this, it is worth thinking how this countryside space reinvents itself, not by receiving the Shakespearean narrative that gives it a staged dramaticity, but by the position of a camera that accelerates it. Against the typical bucolicism, the animals, the farm, and the woods are intercut by a fleeting descent of the lens through its social configuration. The countryside is perceived as this isolated space where power is concentrated, where the landowner who kills his brother to marry his sister-in-law faces the insanity of his nephew in revolt, where the death drive establishes the boundaries between properties and radicalizes the passage of time.

The crossfire of these filmic movements finds a semantic settlement in the textual floor that at points levels the frame. One must realize that the function of the written word in The Inheritance is not to replace the recording of the dialogues. Most of the time the text on screen is rightly playing an ambiguous role between reality and the unconscious, since it is never accompanied by the movement of the actors' mouths. When the characters decide to open their mouths, they are accompanied by animal sounds, gun shots, or the notes of a guitar that hardly ever leave the frame. For the actors, the text runs on a contravening plane. If these words cannot be explained as being spoken, thought, or narrated, it becomes clear that the effect they impose is in a much more divergent sense than explanatory, like a shock of dematerialization that textual semantics offers to tactile images.

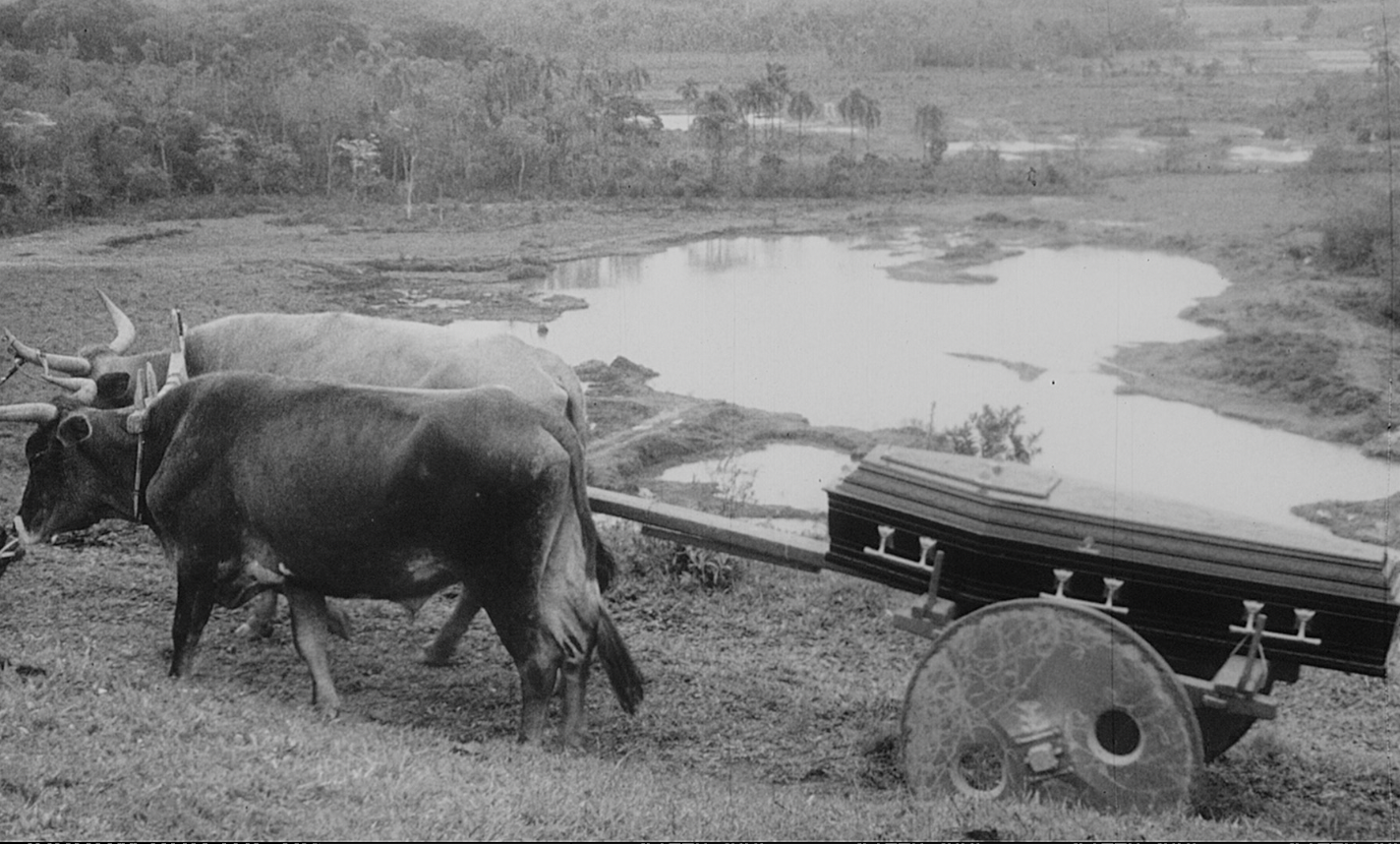

This on-screen text forces us to think about silent cinema, which is fair to a degree, but it seems to be more present in certain framing decisions than in the central experimentation with the text that replaces the voice. A prime example that can exemplify this relationship of Candeias' framing to old cinematic machinery: The opening of the film, an eerie moment in every sense, would not be out of place in any imaginative production of the early part of the century. The opening shot follows a wheel on the dirt floor, the next shot reveals a bullock cart, and then a cut reveals a coffin carried by the vehicle. The sound is not yet that of the guitar player, we are listening to a wailing sound that feels like something out of a Coffin Joe movie, and we follow the burial in continuous camera movements that force the light against the shadow and the pain on Barbara Fazio's face against the sound of her crying. It is an objective execution in sensations that is paradoxically excessive in the mystery of its origins, a feeling that is maintained throughout the film and that makes it seem to have emerged from a vacuum in historical time.

To treat Candeias' cinema in terms of the "primitive" belongs to an obsolete and insufficient critical approach; it is difficult for anyone to watch The Inheritance and not notice a high stage of filmic awareness that is more than just modern. However, since we are talking about a filmmaker who specializes in conceptual knots, his modern experimentalism also needs to be perceived as a receptive ground for the rediscovery of old discoveries, a rare suspension of referentials that doesn't see a great difference between periods of cinema, but which converts and manipulates itself as it inserts itself into particular ideas that are nothing but inventions.

Nonconformity tends to generate an interest in deformity, and the way Hamlet's skull is transformed into an ox skull must give some sign of the earthy path we are treading. The Inheritance is a film of overlapping insertions like any other by Candeias, where the camera infiltrating the terrain goes on to confront the transfusions it ends up committing in its trail of radicalizing the means of filmmaking, but it's also unique in that it maintains that nervous flow in a great sequence of intersecting faces, an approximation of individual expressions that manages to absorb the same weight as grandiose open shots. So if there is anything possible between silent cinema, classical dramaturgy, anthropology, the American Western, and the Italian Western, Candeias is on a cross-cutting journey through this cosmography.