In 2007, I worked as a cataloguer at the Cinemateca Brasileira, Brazil's largest film archive. A major part of the job was analyzing materials that had recently been donated to the archive and it was not uncommon to run into large collections of 16mm films, still kept in Kodak and Ansco film boxes, complete with nicely handwritten notes displaying what they contained. Despite the quantity of home movies that arrived at the archive, prior to this moment I had rarely heard or read about Brazilian home movies and amateur films. After having the opportunity to view some of these films, I quickly became fascinated with them. It was surprising to me that they provided a chance to see life in Brazil in the 1920s and 1930s from a different point of view, meaning not only a glimpse into the lives of amateur filmmakers and their common aesthetics — trembling cameras, faces directly gazing into the camera, jump cuts and discontinuity — but also images of city life that were made from an unofficial perspective. Despite the fact that home movies of this period were produced by bourgeois families, they remain extremely valuable historical documents because they provide us with a closer look at elements that went beyond the middle class home, such as images of historical events, people enjoying leisure time and living within public spaces. In my young cataloguer’s mind, it was obvious that this topic needed further research.

My first encounter with home movies became the starting point of a long path of research that began with a project that focused on the collection of home movies that are deposited at Cinemateca Brasileira. Working on this collection resulted in my dissertation, "Filmes domésticos, uma abordagem a partir da Cinemateca Brasileira”, the research for which was undertaken at the Federal University of São Carlos. My goal in this project was to build further knowledge about this collection of home movies and to bring more visibility to what was an emerging field in Brazilian film historiography. My research focused on establishing the historical roots underlying the arrival of amateur film equipment in Brazil. Later, my aforementioned path of research led me towards learning about the amateur cinema clubs and festivals throughout the 1920s and 1950s that formed in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. As Brazilian home movies remain a field with numerous research possibilities, I am currently studying one of the most important film festivals of the 1960s, the "Festival de Cinema Amador JB/Mesbla" organized by the Jornal do Brasil newspaper, which screened the first short films of filmmakers such as Rogério Sganzerla, Andrea Tonacci, Neville D'Almeida, and many other important filmmakers, editors, producers, actresses and actors who were amongst its participants.

I begin with this personal note because more than ten years ago, home movies and amateur films were not a common topic of discussion among those working in the fields of audiovisual preservation and academia in Brazil. But since then, many “Home Movie Day” events have been organized in film archives and festivals across the country. As a field of research in Brazil, the history of domestic filmmaking once mainly relied on foreign references, but over the past few decades numerous dissertations and theses have been written about the national history of home movies. In this regard, I wish to highlight the recent publication of the book Cinema doméstico brasileiro (1920-1965) by researcher and professor Thaís Blank, a pioneer work within our field. Blank’s work focuses on a wide-ranging field of research that begins with examining the historical roots of home movies and its different genres, taking different collections deposited in Brazilian archives as primary sources. The book provides close investigation of films and contains thorough archival research. The author delineates the process of patrimonialization of domestic cinema and the increasing interest held by national and regional archives in preserving an area of film production (home and amateur movies) that allows different perspectives regarding film history and a deeper understanding of local and regional histories.

The last part of Blank's book is dedicated to the migration of raw material in home movies from their original state to their incorporation into documentary films. The archival fever that has overtaken contemporary cinema has also given a new centrality to home movies and amateur films, materials often used in weaving a personal and experimental cinema. Here I mention some Brazilian short and feature films derived from a much more extensive list that prominently utilize or incorporate home movies:

Supermemórias (Danilo Carvalho, 2013), an experimental film using Super 8mm film from the city of Fortaleza that has been screened in numerous film festivals and has received academic attention.

Extratos (Sinai Sganzerla, 2019), a short-film made with 16mm footage shot by Rogério Sganzerla and Helena Ignez (the director’s parents as well as the major figures of Brazilian underground experimental filmmaking in the late 60s and 70s) during their years in exile, as they escaped the Brazilian dictatorship installed in 1964.

Fartura (Yasmin Thayná, 2019), a collage film with photographs and home videos of Black families and their affective bonding through the sharing of food and common festivities.

Academic research and contemporary cinema has evidently played a pivotal role in the discovery of home movies as a valuable source for history and artistic creation. What also stands as one of the most important conquests of the field is the launch of LUPA - Laboratório Universitário de Preservação Audiovisual, a university film archive dedicated to film preservation education and collecting amateur films from the State of Rio de Janeiro. Part of the Department of Cinema and Video Studies of UFF - Universidade Federal Fluminense, one of the only films schools in the country with a mandatory course on film preservation integrated in the curriculum, LUPA began operating in 2017. Guided by the energy of coordinator Rafael de Luna Freire, film preservationist and professor of the same department, the initial LUPA project nurtured the desire to create a space where the work of researchers and film preservationists could walk hand in hand, shortening the gap between universities and film archives.

Another one of LUPA’s foremost prerogatives is to contribute to the preservation of those film materials that still receive little attention from film archives: amateur films and the wide array of orphan films from the state of Rio de Janeiro. As the concept indicates, orphan films are those which do not possess a clear status of authorship or legal right holdings. They can also be understood as film materials that don't belong in the traditional cinematic dispositif (a narrative feature screened in a movie theater), as they have different functionalities: educational, scientific, nostalgic, along with the myriad other forms of appreciation the moving image can assume. What I’ve learned from my experience with these kinds of materials is that, rather frequently, people are not aware of the historical research value they hold and are unsure where to take these artifacts when practical help in film conservation is needed. As the only film archive dedicated to this kind of production in Rio de Janeiro, LUPA soon received its first donation: The J. Nunes Collection. The J. Nunes Collection holds nine reels of 9.5mm film shot in the 1930s and 1940s. Digitized at the laboratory of Cinemateca Brasileira, these images are now available on LUPA's website.

The J. Nunes Collection gives us an interesting look at amateur film culture and how the production and consumption of moving images worked in the 1930s and 1940s. During this time period, amateur films were often produced by Pathé and many portrayed quotidian life in the streets. The images within the J. Nunes Collection provide insights into how leisure time was enjoyed by a middle-class family in Rio de Janeiro: bullfights, religious festivities, trips to the country and a day at the beach. Carnaval was definitely the favorite pastime of this particular family. The films dedicated to this national festivity also show different forms of capturing the extremely popular celebration, each one with a particular aesthetics.

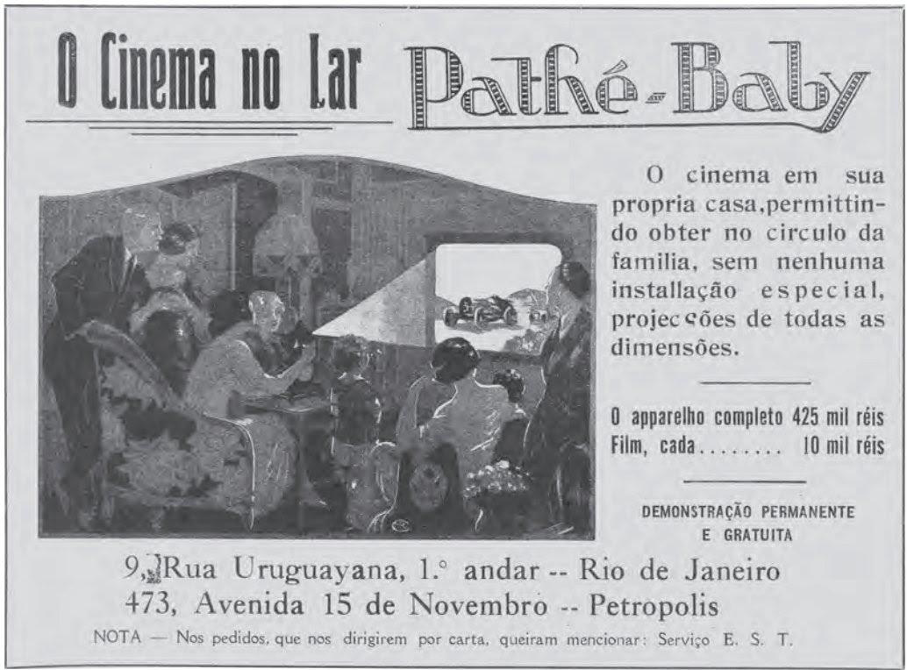

Pathé Baby apresenta: O Carnaval de 1933 was most likely made by hired professionals who sold images to Pathé or produced films exclusively in the 9.5mm format. The film is introduced with steady titles (“Pathé Baby presents”) and serves as news coverage of the parades and street festivities taking place on the Avenida Rio Branco. The corsos,1 with people parading in cars (at the time a very important indicator of social status), the "ranchos”2 and the "sociedades carnavalescas"3, which paraded with large, ornamented cars and gentlemen riding horses: all these can be seen in the six minute reel. These professional reels were sold by Pathé, the French giant that served as the main supplier in feeding a demand for cinematic home viewing in Brazil, while also offering film projectors and accessories. Pathé maintained a consumer market the company had inaugurated in 1912 with the 28mm Pathé-KOK system, known as "Cinematographe du Salon", or “cinema in the living room”. In 1913 this French system was already sold in Rio de Janeiro by Companhia Cinematographica Brasileira. In 1922, Pathé launched its most successful system for domestic cinema, the 9.5mm Pathé-Baby, and in September of 1923 the company established the Societé Franco-Bresilienne du Pathé-Baby, a branch for the Brazilian market. Two months later, the company was permitted by Brazilian authorities to start its commercial activities in Rio de Janeiro. Understanding that the history and preservation of film technology and equipment is a crucial aspect of film history, LUPA has acquired and organized a collection of film cameras and equipment, part of which have been made available to different exhibitions.

In O Carnaval de 1936 and Tourada, Festa da Igreja da Penha e Carnaval, images of carnaval are captured by amateur hands, noticeable through the shots in which the camera comes in close proximity to the dressed up “foliões".4 Even though some of the locations in these films are the same as those that were captured in the more professional cinematic productions of Rio, here we find a rarer depiction of these areas, with spontaneous street celebrations, followed by the adults and children of the Nunes family playing and singing while dressed up as Chinese dancers. The beauty and the energy of the crowded streets, the body movements, the joy of a group of children; this spontaneity gives the spectator a very intense feeling of the cultural and existential meaning of carnaval, a feeling of rare translation. Expressions of joy can also be found in the core images of Festa da Penha, a religious celebration in a traditional neighborhood of Zona Norte, and in the scenes of the bathers in Balneário da Urca. The film displays a day spent at the beach and views of the Urca Casino and the Sugar Loaf, both famous sites for tourists. In a different film, Amador J.Nunes saúda todos os amigos e presentes, amateur dexterity can be seen in nicely shot intertitles, as the film begins as a sort of reflexive home movie: a woman holds an amateur 16mm camera and points it directly at the main camera which is shooting. This reflexive gesture denotes the popular interest in cameras and in the act of filming itself, and we understand from the film that amateurism is about the sheer love of image making and the subjective cinematic experience.

The process of safekeeping these images and making them accessible are gestures of extreme importance towards building the perception that home movies and amateur films are vital materials to be studied and preserved. As a regional film archive, LUPA has amassed different collections in the past few years, including important personal archives such as documentation regarding Carlos Fonseca, film critic and producer with a long career in cultural management at institutions such as Instituto Nacional de Cinema (INC), as well as the materials of many other amateur filmmakers and collectors. These new collections have been revised and organized by students, and the documentation is made available through LUPA's website even while the cataloguing work is still in process, making LUPA an indispensable space for practice and experimentation with strategies for granting access to archival collections. Decentralizing preservation efforts is an urgent issue in Brazil and LUPA is an example of how we can observe that home movies and amateur films are important sources for local histories. The maturation of what was a new field of study ten years ago is a cause for celebration, as amateur and orphan films solidify their place as one of the central initiatives in contemporary film preservation.

1. A parade of cars, very common in Carnaval celebrations of the first decades of the 20th century.

2. A group of costumed Carnaval goers playing musical instruments, singing and celebrating in the streets.

3. Associations dedicated to promoting parades and competitions during Carnaval. Some researchers indicate that they were the inspiration for the Samba schools.

4. Foliões are people who participate in the Carnaval parties.