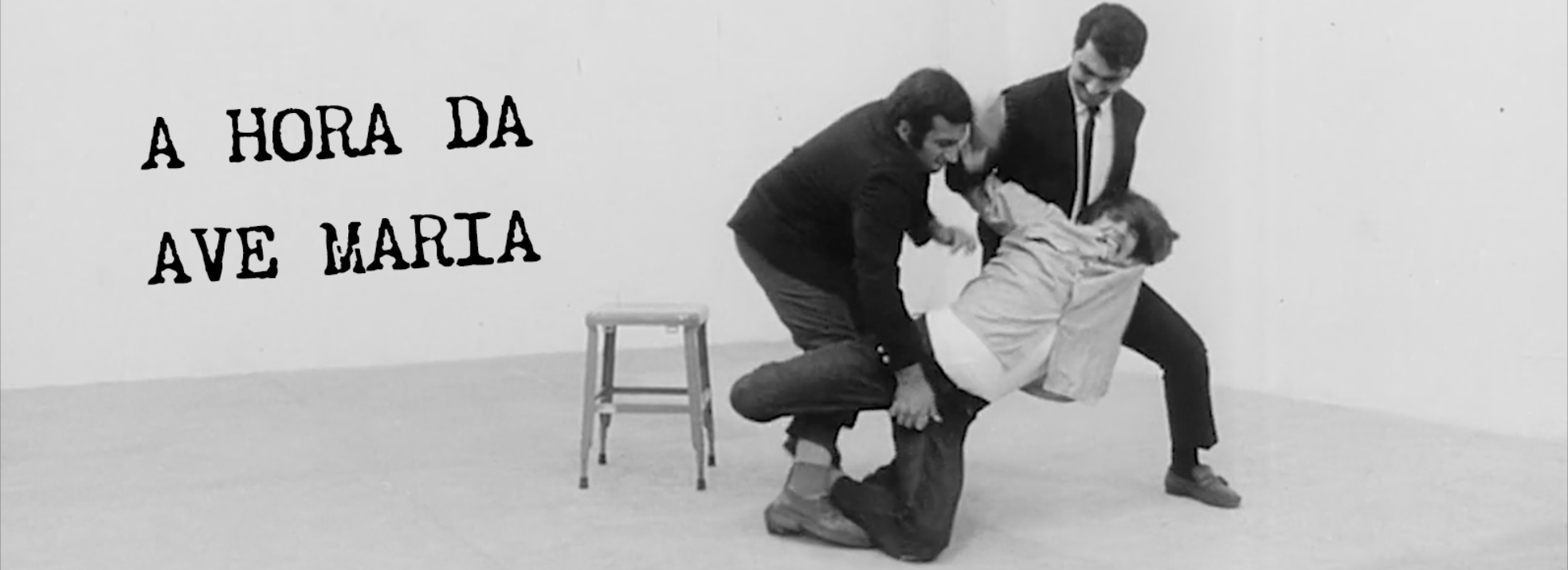

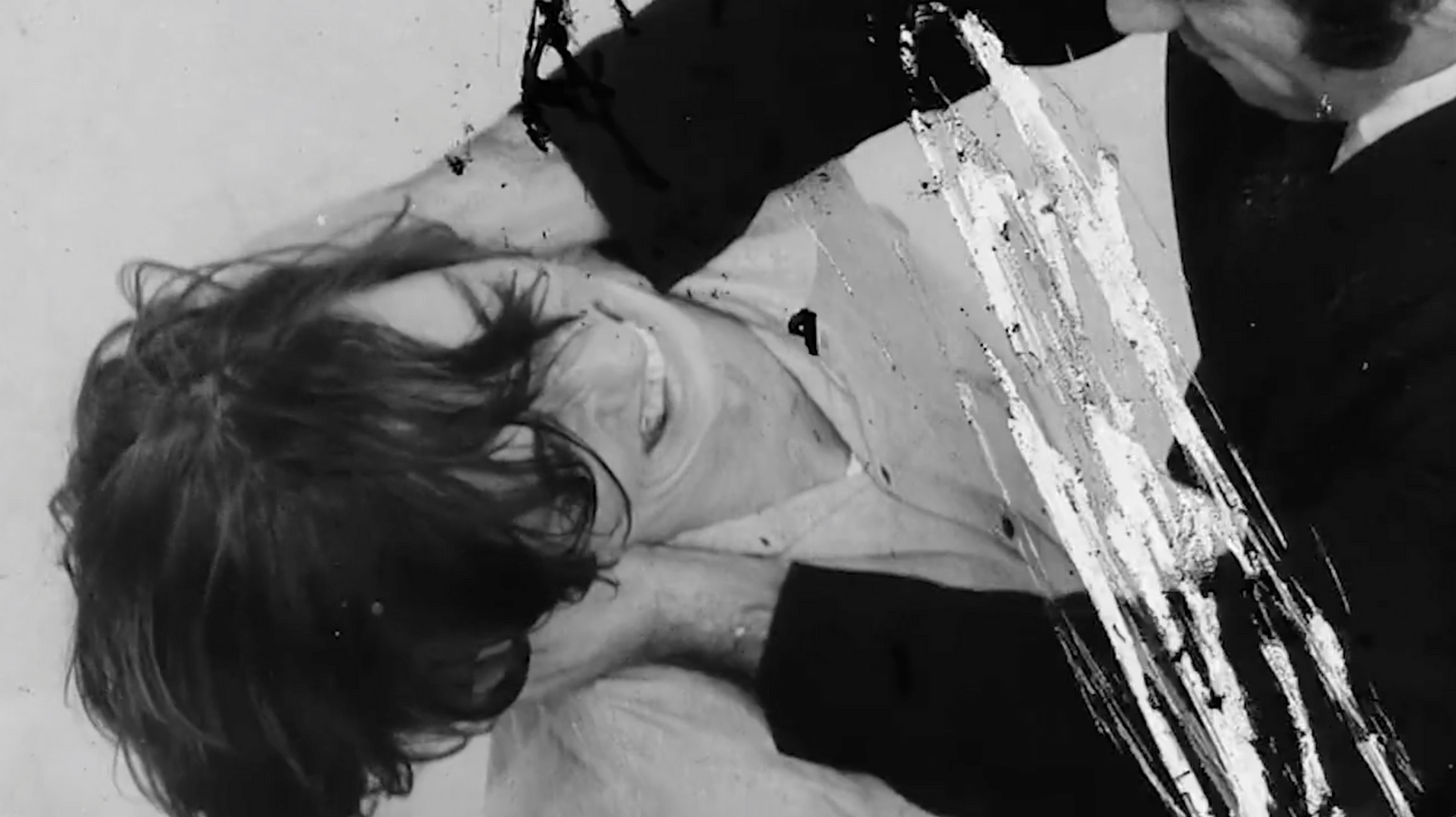

While speaking to a bureaucrat who interrogates him, Edson, played by Joel Barcellos, is surprised by the ringing of bells. He is in a bright, sparsely furnished room, and has been brought to this strange environment by unidentified agents. The bells in the distance only confuse him further. The woman in front of him explains with a mischievous smile that "Hail Mary time" has come. And the following sequence unfolds to the sound of "Ellens dritter Gesang", the musical piece by Franz Schubert popularly known as “Ave Maria”. What takes place on screen, however, brutally contrasts with the music: there is a violent sequence in which Edson is beaten, tortured by two of the agents who kidnapped him. The image of the film's protagonist being beaten is one of the most memorable when discussing it, and not by chance: a significant portion of the film’s ninety minutes is dedicated to showing Barcellos' character being subjected to various batteries of interrogation and torture.

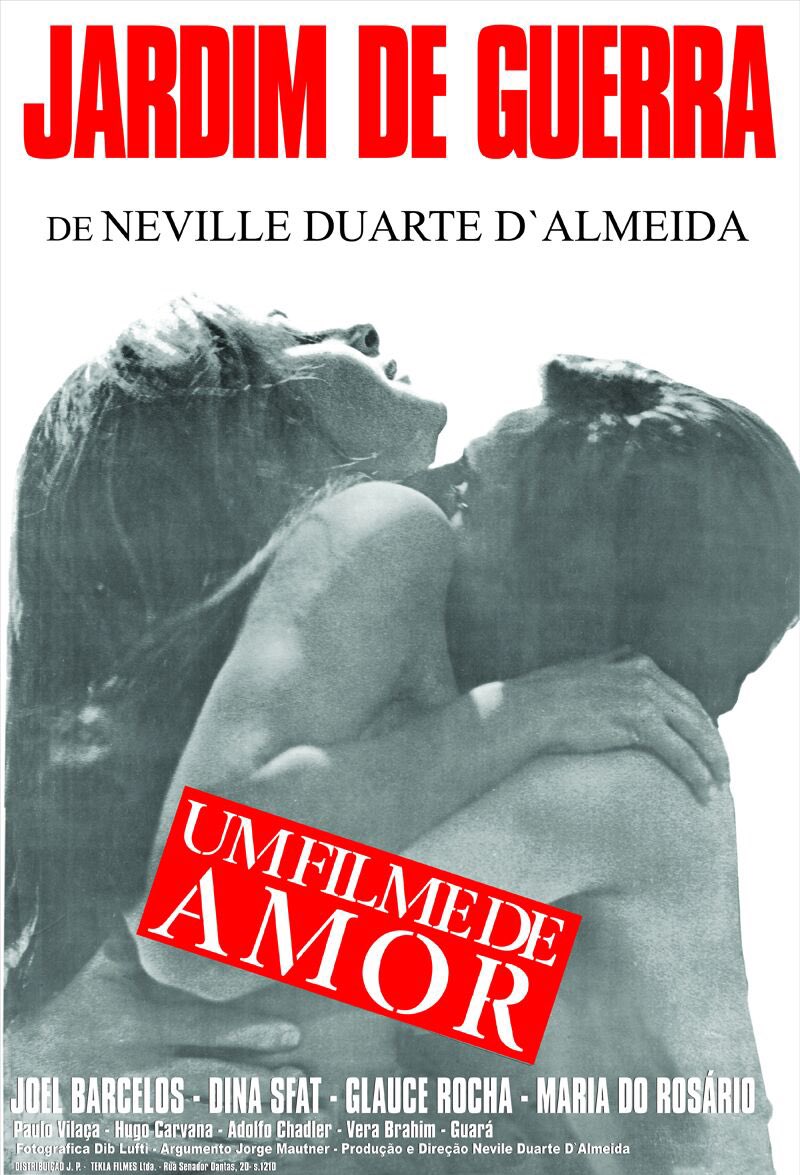

We are referring to Jardim de Guerra, the first feature film by Brazilian filmmaker Neville D'Almeida, filmed and released in 1968. Before that, the director had already made some filmic incursions, such as the short O Bem Aventurado, made for the JB-Mesbla festival in 1966. His first feature, however, is much more ambitious than his short. Originally from Belo Horizonte, capital of the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, D'Almeida had immigrated to the U.S. shortly before the civil-military coup that resulted in the dictatorship that would rule the country from 1964 to 1985. His goal was to study cinema in New York, but he realized that it would be a fruitless effort when he discovered that the professors in New York had an excessively American vision of cinema.

Working as a waiter and having dropped out of school, D'Almeida found an oasis in another Brazilian who was self-exiled in the same city: writer and musician Jorge Mautner. Together they wrote the screenstory and the screenplay for Jardim de Guerra. When Nelson Pereira dos Santos went to New York to shoot some sequences for his film Hunger for Love, D'Almeida helped him as assistant director, and went back to Brazil with him. Once back in Brazil, D'Almeida began the process of raising funds to film his first feature, which would be produced independently.

Jardim de Guerra is a difficult film to situate between Brazil’s film movements of the 60s. It definitely does not belong to Cinema Novo. D'Almeida had indeed seen the productions of directors such as Glauber Rocha and Carlos Diegues while still in New York. They greatly influenced him and motivated him to return to Brazil and make Brazilian cinema. But D'Almeida's film has other concerns, other discourses, other processes. Nor does it belong to the movement known as “Cinema of Invention” or “Cinema Marginal”; helmed by Rogério Sganzerla and Julio Bressane. When one speaks or writes about the early part of Neville D'Almeida's career, which comprises films that are more experimental in language and associated with the counterculture between the 1960s and 1970s, his name is commonly associated with the Cinema of Invention. This is fundamentally wrong; it is an obvious, but very widespread mistake, even among the press of the time. According to D'Almeida, he has always been disowned by Cinema Marginal. Who, then, is Neville D'Almeida? He is a contemporary of Cinema Novo and Cinema of Invention, but he doesn't fit into those labels. D’Almeida therefore lives outside any groups - even though Jardim de Guerra has, in its pulsating heart, all the spirit of the period in which it was shot.

Having covered the most important extrafilmic information, it is necessary, of course, to present some filmic context in order to write about Jardim de Guerra, because it is a feature film that has been little seen and little remembered for reasons to be discussed later. Its main character, Edson, is a young man. He lives in the city of Rio de Janeiro, which is where the film takes place. Actor Joel Barcellos looks about twenty-something in the role - which, by the way, won him a trophy for Best Actor at the Brasília Film Festival. The viewer is not given much information about his background, but it seems safe to assume, from what is presented, that he is a young man who grew up poor, or lower-middle class. And in the very first sequences of Jardim de Guerra, Edson is shown having his first interactions with a young filmmaker named Maria (played by Maria do Rosário). With a 16mm camera in hand, she films him in some jocular shots. They joke, film each other in the nonchalance of a newly graduated couple sharing a sublime moment. The two begin a sort of courtship (although Edson has sexual relations with other women, and the film does not relay whether this happens with her knowledge). After this courtship, Barcellos’ character starts to enter new social circles that weren’t accessible to him before.

To initially dwell more on narrative aspects than on imagery, aesthetics or language may seem a futile exercise. Nothing in the film, however, is there without purpose, because narratively, Jardim de Guerra wants to discuss the social issues which compose the cultural amalgamation around which it is built, and in how they are dealt with, visually.

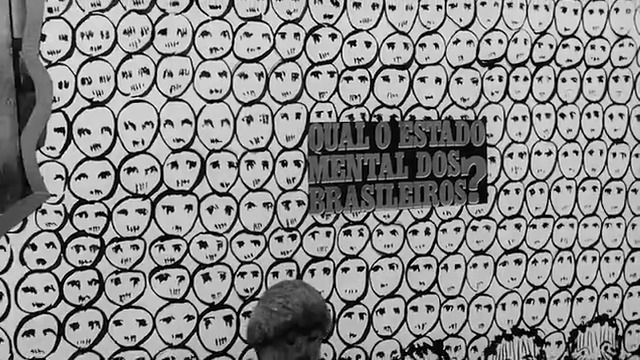

What matters at this point is that, from the moment he establishes his connection with Maria, Edson starts attending the parties of intellectual, university-linked leftists; those that were nicknamed "the festive left" by the acid humor of Brazilian chroniclers of the time, such as Paulo Francis and Nelson Rodrigues. Safe behind the walls of the rich apartments in the south zone of Rio de Janeiro, Edson suddenly finds himself up to his neck in ideas that were deemed "subversive" by the dictatorship ruling the country at the time. However, D'Almeida's perception is that a significant portion of the people in that sort of environment were more interested in the festive aspects of this type of social gathering than in the social agendas that supposedly brought the attendees together.

This perception is reflected in a sequence set in one of these parties: to the sound of a Nina Simone record, the exponents of the party interact with each other, drinks and cigarettes in hand; Edson tries to interact, even if initially in a timid way. Cut to a character played by legendary actor Antônio Pitanga, standing in front of a wall (and alone in the frame, although speaking to a would-be group of listeners offstage). Pitanga delivers an impassioned, powerful speech about the racial inequalities to which black people have been (and still are) historically subjected in Brazil and in the world, stressing that the black power movement is not something relative only to the USA, but a movement with a global scale.

Pitanga speaks for a few minutes, but the film soon cuts to the party carrying on as usual in a light, relaxed atmosphere - ironically, still under the music of Nina Simone - while the figure who had preached the revolution among the partygoers finds himself isolated, leaning against a wall, with an expression of desolation and weariness. His speech is eventually taken up, only for the action to return again to the party: no matter how much he speaks, his ideas have no effect on these people.

Anyone minimally familiar with the context of the racial struggles in the United States might find several ideals propagated by the character in his speech that are aligned with a vision closer to Malcolm X's thought than to Martin Luther King's - and curiously, Pitanga also plays an intellectual of Malcolm's ideals in Antunes Filho's Compasso de Espera (1973). It is not so important here where the discourse is ideologically inclined, but where it comes from. The black racial agenda has existed in Brazil since the moment when several groups coming from the African continent arrived in the country as enslaved prisoners to be sold. But in Pitanga's speech, what remains clear is the influence of foreign organized movements, from the USA, even if the character stresses the universality of these ideals. The fact is that all the intellectual charge, the weight of the message, all the guidelines inserted by D'Almeida and his co-scriptwriter Mautner in the film, form a kaleidoscope of everything that the two absorbed during the years they lived in New York, of everything that was simmering in the local political and artistic counterculture of that period, and that developed in parallel in Brazil, whether organically or through external influences.

In addition to talking about black power, Jardim de Guerra talks about the growing feminist movement, reflected here through a speech intoned by actress Dina Sfat. Among the other topics are the need for the preservation of the Amazon territory, recreational drug use, free love and sex, the rise of China as a world superpower, the history of leftist revolutions around the world, and above all, torture.

With the intention of getting money to finance a film for Maria, Edson goes to the house of a criminal (played by the brilliant Paulo Villaça, in a brief performance) and offers to perform a service for him. The following sequence shows Edson in a port area, with a suitcase in hand, ready to make a delivery. It is there that, when he thinks he has found the person to whom he should pass the suitcase, he is shepherded into a car. Edson is taken to an unknown environment, where moments later he hears the bells announcing Hail Mary time. The entire sequence of Edson's drive from the port area to the place where he will be beaten is conducted silently; D'Almeida and director of photography Dib Lutfi (cameraman of Glauber Rocha's Terra em Transe) follow Joel Barcellos from a safe distance, as if they were following an abduction in real time.

From then on, Edson spends a considerable portion of the film being interrogated and tortured, with brief pauses in between. Among his torturers, some recognizable faces: actors Hugo Carvana, Guará Rodrigues, Glauce Rocha, the aforementioned Dina Sfat, and even filmmaker Nelson Pereira dos Santos, who here participates in retribution for the help provided by D'Almeida in his film Fome de Amor. During our protagonist's first moments in captivity, the reason he was taken there is revealed: the suitcase he was carrying held a machine gun.

D'Almeida never makes it clear that the people who are subjecting the main character in the film to torture and interrogation are government officials. Nothing is said about the military, police, or DOPS. The ambiguity in all this is likely intentional; even the few films that openly discussed torture during the first years of the military dictatorship did not dare to link it directly to the government. If the director of Jardim de Guerra had done so, it is hard to know what might have happened to him.

Given such range of subversive agendas and the feature's dedication to portraying torture, the fate to which it was subjected was merciless. Right before its second commercial screening at the Brasília Film Festival, the most traditional event dedicated to Brazilian cinema, Jardim de Guerra was forbidden to be shown. The film was confiscated and submitted to the Federal Police Censorship of the military dictatorship.

This happened in November 1968, one month before the Institutional Act number 5, which made the military regime even bloodier and started the period that became known as "os anos de chumbo".1

The film was only properly censored in 1969. It was subjected to a series of cuts that aimed to gut it of all content considered ideologically dangerous. The censored copy only began to circulate in 1970, being considered by critics like Jairo Ferreira as truly unintelligible due to what had been subtracted from it.

More than fifty years later, Jardim de Guerra remains absent from the annals of the official historiography of Brazilian cinema - perhaps because it is not clearly affiliable to Cinema Novo or Cinema de Invenção, perhaps because it was censored so abruptly and deprived of a more significant impact on the country's cultural scene (despite its innovative imagery: it is one of the first Brazilian films to integrate posters and still photos to the elements of film language).

A single uncut 35mm copy of the feature survived, as it was rushed to Europe to open the first Directors' Fortnight in the history of the Cannes Film Festival, in 1969. In 2018, after spending decades in the archives of a German cinematheque, the complete version of Jardim de Guerra returned to Brazil, to be stored and preserved by the Cinematheque of the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro. And the rest, as they say, is history.

1. "the leaden years"