This is not a list of films that influenced the style or the making of my film Vassourinha: The Voice and The Void.

I just cannot create such a list, because when I went to make the film I was completely absorbed, or, possessed (as one could say, in the sense of the trance in black religions) by Vassourinha and his mystery. I found that I was operating in new and unprecedented territory, although I acknowledge there is a past tradition as a found footage filmmaker.

Born in São Paulo city, Vassourinha was an elusive sign, a forgotten personality of Brazilian music doomed to be a tiny footnote of history (at least, until the film was released). In my research and production process, made in collaboration with Bernardo Vorobow, Vassourinha appeared and disappeared, full of enigmas to be dis/covered.

Before and during the making of the film, I had no other films to lean on as references or inspiring sources. Instigated by Limite’s proposition, I would cite films that are in dialogue with “Vassourinha” in four aspects and axes that are groundbreaking yet essential for the film’s structure and concept, and to allow the film to develop its premises.

- Vassourinha recorded only 12 Samba songs, in six 78 rpm records released in 1941 and 1942, but since 1935 he was a star, singing with the famous Carmen Miranda and Francisco Alves. Therefore, I will mention films that deal with the Brazilian music genre of Samba as a treasure of national heritage and a reservoir of beauty for the nation.

- Vassourinha is my first film to work a motif that is foundational for my filmmaking: death and mortality. The final sequence in the cemetery (where Vassourinha is buried) proposes a sort of vengeance by means of Carnival and rapture. My film works upon “the poetics of rupture, the history of ruins”, as coined by Rubem R. M. de Barros in his master dissertation (and book - Poéticas de fragmentos: história, música popular e cinema de arquivo, 2014) about my film. So, I will also mention films that deal with death, ghosts, and reanimating the past.

- Vassourinha was edited by Cristina Amaral, its sound was edited by Eduardo Santos Mendes, and its end sequence was cinematographed by Carlos Reichenbach. Therefore, I will mention at the end of this list one film directed by Reichenbach, one of the most cinephilic and creative filmmakers of Brazil, which was edited by Cristina Amaral and whose sound was edited by Eduardo Santos Mendes too. The main character of this film is a black woman living and working in São Paulo.

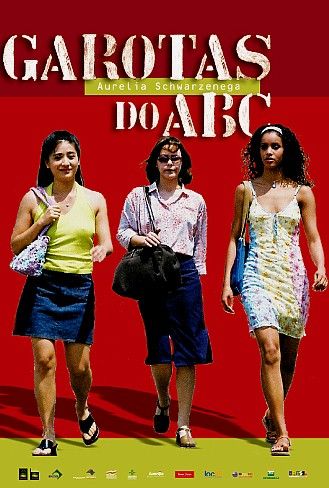

Garotas do ABC (2004, 35mm) by Carlos Reichenbach.

São Bernardo (a city of the São Paulo state) is a region of textile and metallurgical factories where a group of female workers live their daily routines of hard jobs, dreams and illusions. The main character is Aurélia, a beautiful and daring black woman, and a fan of actor Arnold Schwarzenegger who falls in love with a young muscular guy from a Neo-Nazi group that carries out crimes against northeasterners and blacks. Under a misleading label of social melodrama, the film depicts human relations in a complex and vibrant way.

Serras da Desordem (2006, 35mm) by Andrea Tonacci

A documentary essay and a powerful cosmopoetics about a world on its way to being lost. A search for a personal identity that is also a quest for that of a nation. The film reconstructs and reproduces the trajectory of Carapirú, an Awá-Guajá Indian, who saw his tribe invaded and massacred by landowners and loggers. A surviver himself (always under threat of death), Carapirú manages to escape and begins a long journey through hinterlands, cities and forests of different regions of the country, coping with all sorts of aggressions by white men tow

You Don’t Know Me (2014, digital video) by Katia Maciel

Kim Novak (from Hitchcock’s “Vertigo”, 1958), or, aka Madeleine / Judy (in her bipolarity fictional tensions and tenses), walks mysteriously through a song by Caetano Veloso (“You Don’t Know Me”, from his record Transa, 1972). A found footage poem that sets in motion the meaning / seaming of looks and acts, postures and gestures, muse and music. A sort of sortilege that confounds perspectives about identity, ghosting and pretending.

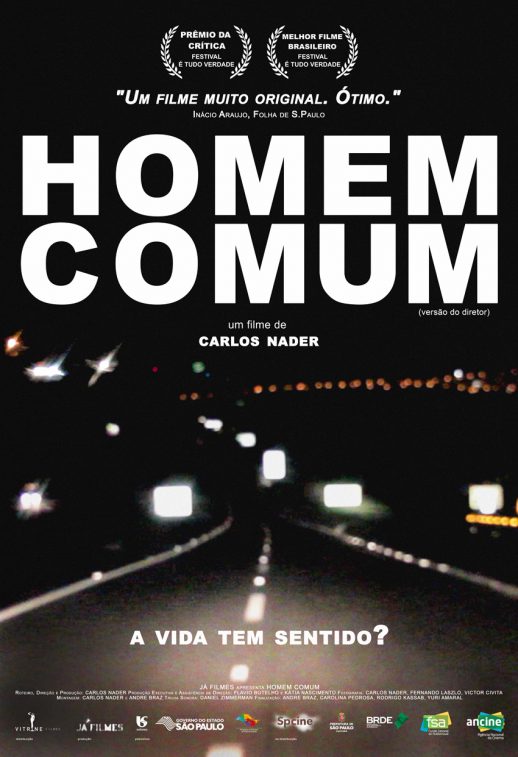

Homem Comum (2015, digital video) by Carlos Nader

A film essay about the simplest and most complex things of life (and death). In 1994, Nader met the truck driver Nilson de Paula and for the following 20 years he shot the daily routine of that man and his family. On the road and during the cinematic process, Nilson’s common and ordinary reality is intermingled with one of the most uncommon and extraordinary films of cinema, “Ordet” (1955) by Carl Dreyer. Between the ethnography and the epiphany, this work operates miracles of cinema and of life in reflecting and traversing (and transcending) each other – and ourselves.

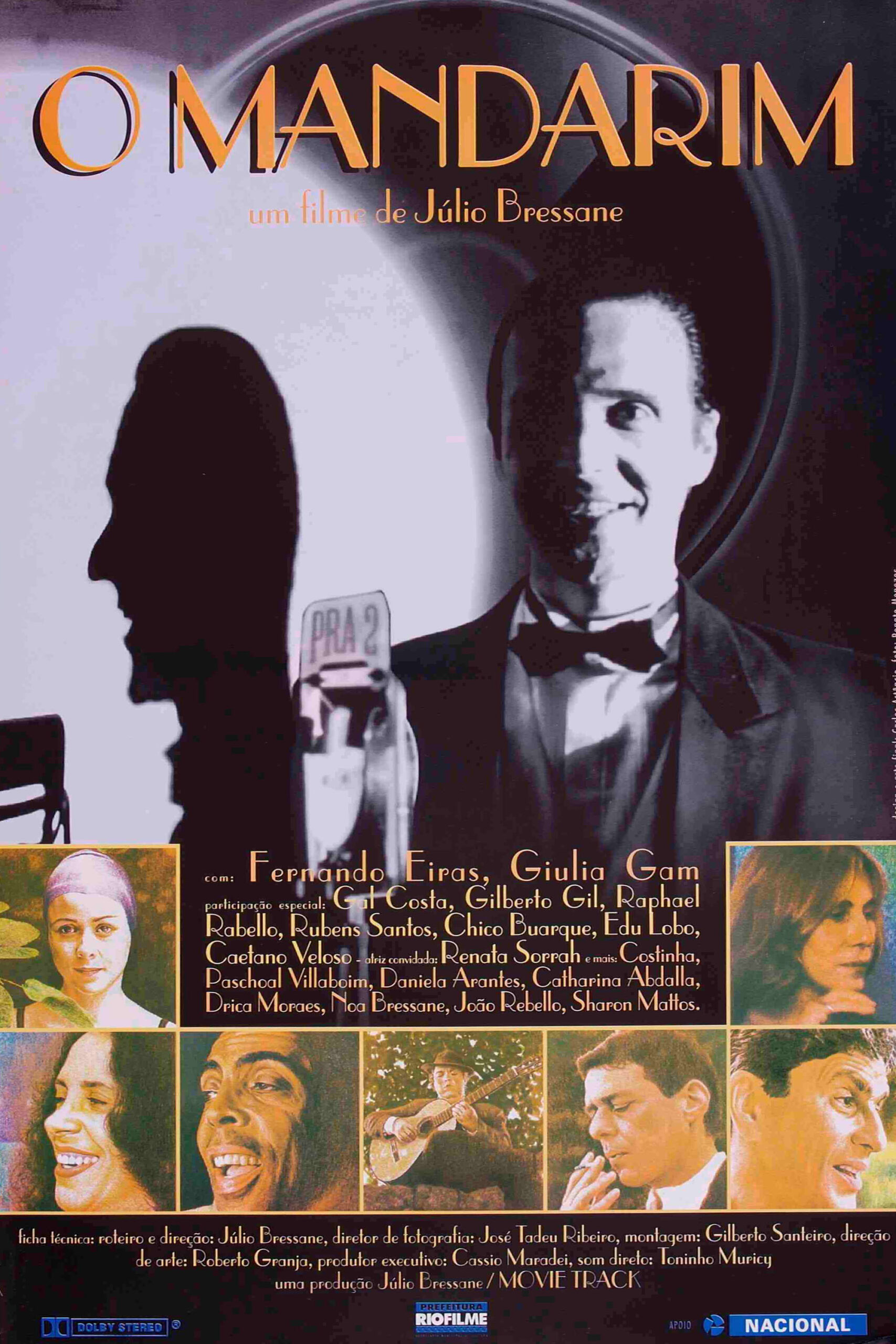

O Mandarim (1995, 35mm) by Julio Bressane

An unconventional biopic of Mário Reis (1907-1981), a key (and yet out of key) singer of Brazilian Radio during the Golden Era. In a cultural and semiotic interplay, famous singers, musicians and composers (not contemporary to Reis's time) play real characters of his time period: Gilberto Gil plays Sinhô, Gal Costa plays Carmen Miranda, Chico Buarque plays Noel Rosa – but Caetano Veloso plays himself. The Brazilian popular music as utopia, somewhere over the rainbow, out of normal groove.

A Morte de Um Poeta (1981, 16mm) by Aloysio Raulino

An uncompromising documentary around the funeral of Samba composer Angenor da Silva, best known as Cartola. A Brazilian musician discovered later on in life, Cartola recorded his first album when he was 66 years old. The main stage of this elegy poem, shot and edited by a poet of image and words, is the cemetery where the black author of Sambas such as “As Rosas Não Falam” and “O Mundo É Um Moinho” was buried on November 30, 1980.

Nelson Cavaquinho (1969, 35mm) by Leon Hirszman

The daily routines of Samba composer and singer Nelson Cavaquinho (1911-1986) shot and edited in Brechtian detachment, this short displays reflecting Marxist emotion and sober engagement. The director is one of the leaders of Cinema Novo. At his neighborhood of Lapa (Rio de Janeiro) and his house, along with his family and friends, the Samba poet of melody-melancholy reminds us of Brazilian painter and printmaker Oswaldo Goeldi.

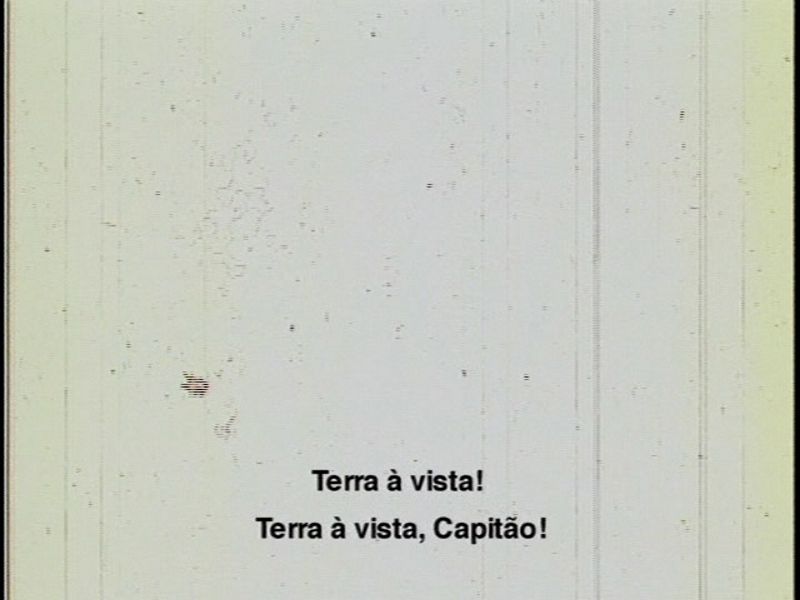

Vera Cruz (2000, video) by Rosângela Rennó

“Vera Cruz” is a video without images (the blank and scratchy filmstrip) only containing subtitles accompanied on the soundtrack by Pero Vaz de Caminha’s famous letter to the King of Portugal about the Discovery of Brazil (1500), along with sounds of the sea and wind. Dealing with a foundational narrative (the arrival of Portuguese colonizers to Brazil), it is an “impossible documentary”, as the artist called it.

Os Sonacirema (1978, 35mm) by André Parente

This film does not have any figurative images, only transparent and veiled points in transitions (fade-in / fade-out), with a voice-over narration spoken by several voices reading a document about an Indigenous Brazilian tribe that stretches from the Oiapoque to the Chuí regions of Brazil. Under the title, which is "Americanos" spelled backwards and alludes to “cinema” and “sonar”, the movie screen turns into a mirror for the imagination of spectators.

Congo (1972, 35mm) by Arthur Omar

“Congo” is composed almost in its entirety of words and quotes by scholars that directly address the history and style of the “congada”. There are also very few images vaguely related to the subject. An exemplary example of “Anti-Documentary, Provisionally” coined by Omar, the film expresses the impossibility of knowing its subject, particularly according to class and intellectual points of view. A radical anthropology of glorious film grammar.