I.

Anyone interested in understanding in detail what was happening in the Brazilian cinematographic scene from the mid-1950s onwards cannot do so without reading two of Brazil's foremost contemporary interdisciplinary scholars, Mario Pedrosa1 and Sérgio Augusto.2 Through their writings we can understand the two paths of the Brazilian ideological annexation, which still haunts us in 2021. Pedrosa provides a detailed account of the US neocolonialist movement since the war for Cuba's independence and its political and economic consequences up until the consolidation of the US occupation in the name of democracy in several Central and South American nations. This ranged from good neighbor relations and entertainment soft power to the culmination of military coups, as occurred in 1964 in Brazil. Sérgio Augusto, on the other hand, took carnival musical films as his subject matter and evaluated the creation of popular entertainment for the sake of alienation. This was very welcome by the Vargas authoritarian system and, later, essential in the progressivist propaganda of Juscelino Kubistchek. Both writers take the reader back to a Brazil overtaken by obscure interests, when romantic and conformist discourse was more valued than the art of cinema. Against this backdrop, the chanchada carnavalesca and the epic dramas taken from national literature and folklore entertained the general public and distracted them from more urgent problems.

In its attempt to create its very own dream factory, with its stars and stars from the tropics, Brazil fostered a number of figures that, although part of a programmatic system, were able to provide a much needed historical critique at the right time.

When we turn to the story of Anselmo Duarte, we see that he clearly understood when his peak as an actor was over and when his career as a director was on the verge of taking off. Anselmo arrives in the in-between period that separates the cavadores (diggers)3 from the cinemanovistas, from precarious cinema to the luxury of studio productions. Anselmo is the profane intersection that unites the fake chandeliers of Vera Cruz to the raw, erratic and prophetic films of Cinema Novo. He skillfully moved between the image of the virile star to having the reputation as an internationally awarded director at a moment when the national cinema had not yet managed to break the boundaries of its own borders. And he did so full of empiricism and creative and entrepreneurial zeal.

At the end of the 1950s, when Brazilian cinema was in its early infancy, Anselmo had already taken his first huge step towards establishing a career as a film director. With Absolutamente Certo! (1957), the actor and filmmaker gathered all the pieces that were falling apart from the foundations of Atlântida, such as its beautiful musicals, and the comedies of manners4 produced by Vera Cruz during their final years, trying to find some kind of box office success between the two. Using the fixed formulas learned from his mentor Watson Macedo, Anselmo made a light, intelligent, rhythmic and very funny musical comedy, with a repertoire marked by great names of music of that time, from Betinho and his Conjunto to Trio Irakitan. An immediate success, the film earned its director and associate producer a large sum of money, enough for Anselmo to be sure that he could push the boundaries even further with his next production. Cleverly, he invested his income from Absolutamente Certo! in a sabbatical trip to Europe, where he intended to study the in-fashion cinema over there. Like a flâneur of the modern world, Duarte wandered aimlessly, but with a very clear plan in mind. "[...] I went to the Old World that was taking the last cultural pills to remedy the hangover of World War II. I went to experience the Nouvelle-Vague up close. I went world-wandering".5

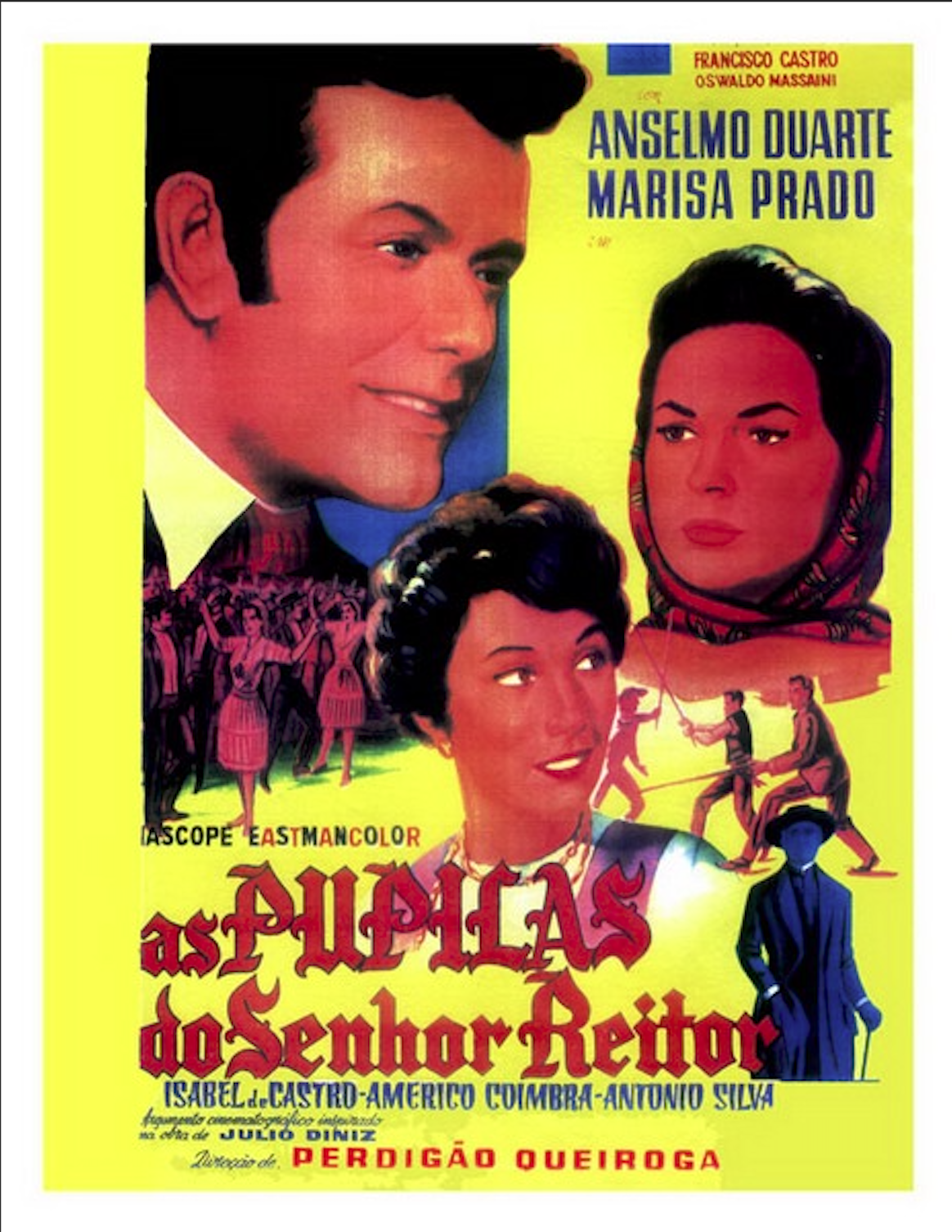

Now on European soil, Duarte began his journey of personal discovery in Portugal, starring in Perdigão Queiroga's As Pupilas do Senhor Reitor (1961), not bad for a newcomer to an industry completely different from the one he was used to. However, with his physique du rôle, it would naturally not be difficult to assume the role of young Daniel in Queiroga's film, as described in the pages of Júlio Diniz's original novel. When the shooting was over, Duarte went to Paris and enrolled in the renowned IDHEC (Institut des Hautes Etudes Cinematographique) and began to negotiate with local producers to make a feature film entitled O Rapto. However, the film never got beyond the first scenes due to a bureaucratic obstacle that inflated the production budget. With the project cancelled, Duarte started to wander around Paris doing quick jobs for press teams and documentaries. He even became a sort of tourist guide recommended by Itamaraty.6

Anselmo would go on to visit England, Italy, Switzerland and Spain, always playing various roles in local film crews and studying new film technologies. The great turning point, however, began in 1960, when the filmmaker decided to go to the Riviera to attend the Cannes Film Festival of that year. There, he was introduced to great European cinema personalities, influential journalists, and strongly opinionated critics.

That year’s edition of Cannes was simmering with anticipation and intrigue. In 1959, François Truffaut radically changed the festival’s standards when he received the best direction award for The 400 Blows. The nouvelle vague had imposed its ethics and aesthetics on the old school of French cinema. Youth was vibrating and demanding the attention of the dinosaurs of the film industry. The magazine Cahiers du Cinéma asserted itself as the spokesperson of the renewal. In 1960, Anselmo would see Federico Fellini receive the Golden Palm for La dolce vita and Antonioni would share the jury award with Kon Ichikawa. It's worth noting that even with the signs of renewal, Cannes was still reluctant to give up on traditional cinema, continuing to award prizes to industry veterans. However, they were beginning to show an inclination towards the experiments that would overtake cinema throughout the decade.

What really impressed Anselmo Duarte that year at Cannes was an immense colorful poster announcing the world première (for next year’s Cannes edition) of the epic The King of Kings (1961), a Hollywood portrayal of the Passion of Christ directed by Nicholas Ray. It was then that the idea came to him, shared with a Portuguese journalist friend: "I've seen and heard enough in Europe. I'm leaving and next year I'll be here to win the Palme d'Or".7 The assertion denounced his indignation with the "Hollywood Jesus Christ in a satin robe". Anselmo wanted to create a parable of Christ in the third world, of a common man called to a divine mission. Even mocked by his new friends, who told him how difficult it would be to compete in Cannes, Anselmo ignored them and eagerly went back to his home country, with confidence and new ideas.

It was almost two years ago that I was living in Europe. In Italy I learned about dubbing and co-production techniques. In Switzerland I noticed the development of a new electronic device, the tiny "nagra", which replaced the clunky Hollywood ones with many advantages. In Portugal I was amazed to see German, French and Portuguese artists acting in three languages, without understanding each other. I was astonished by the scenography of the Spanish plastic artists. In France, I absorbed the romantic scenes, the agility of the technical team on set, the scientific cinema and the ritual of the Cannes Festival. In England I appreciated the power of interpretation, the thriller, the narrative [...]. But the most important lesson I learned in England was the black-and-white cinematography.8

The stay in Europe provided Anselmo Duarte with more efficient training than any audiovisual college course would have and put him at a curious crossroad that would merge his previous experience with new trends, opening doors for the generation to come.

During the first year of his return to Brazil, Anselmo made little progress with his project of the suburban Christ. His ideas were not working, and perhaps there was no time to carry out his confrontation with MGM's blue-eyed Jesus. It was only a few months later, when he saw the play O pagador de promessas by Dias Gomes, that Anselmo understood it contained all the elements he sought for the representation of mysticism and religiosity in Brazilian culture. But there would be no time to adapt the play for the 1961 edition of the Cannes festival. The film would have to be made in 1962, with him keeping his sights on the Palme d'Or for that year.

II.

Watching the movie version of O Pagador de Promessas, it is hard to imagine how the director dealt with the many challenges which were presented to him as he was trying to fully realize the project. There were difficulties in his relationship with the author of the play who did not approve of his adaptation, difficulties in casting, and Duarte had a strained relationship with Norma Bengell, one of the stars of the film. It's not hard to imagine the reasons for all this trouble. Anselmo had in mind a flawless work. To achieve this, he developed psychological and narrative aspects that were not in the original play, inserted new characters and dialogue, and used striking photography and decoupage with no concessions beyond what he considered innovative and spectacular in the eyes of the audience.

The arrival of Anselmo Duarte and his team in Salvador was considered an event. In Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, cinema was stagnant. There was still a vestige of Rio's chanchadas and the people from São Paulo were fighting to make new productions possible. They were looking to collaborate with independent professionals who were beginning to establish themselves in the area around the city’s old bus station, known as Boca do Lixo. There, cheap but creative films were being made. Anselmo worked with one of Boca do Lixo producers, Oswaldo Massaini, whose company Cinedistri had already funded the first success of the now ex-star, Absolutamente Certo!.

In the 1960s, Bahia was seemingly a more promising place to be for those interested in working in the cultural industry. The Federal University of that state was under the command of progressive minds, and young students were encouraged to dive into the cultural universe without fear or limits. One of these students was Glauber Rocha, just over twenty years old at the time and already a great agitator in the local cinematographic scene. Glauber was a critic for the local newspaper, had made a short film, and was preparing his first feature film. As spokesman for his generation, he frequently received artists arriving from the south of the country and was responsible for introducing them to the sights and figures involved in the new wave that Bahia was making in literature, theatre, and, above all, in cinema. After all, there were already two important productions from Bahia in the context of that time: Redenção (1959) and A Grande Feira (1961), both by Roberto Pires, and soon others would come out.

With Glauber, Anselmo was able to learn more about the local culture in order to enrich the story of O pagador de promessas. From Anselmo, Glauber was interested in learning about the fresh filmic repertoire he had acquired in Europe. This exchange, though rich for both sides, would in the future become a generational dispute that irrevocably drove them apart. The dispute would eventually become public, with open verbal attacks against each other in the press. Glauber died early, at the age of 42, without any chance for them to reconcile. Anselmo, in his biography, remembers his colleague with a combination of nostalgic affection and melancholy for the broken friendship. Brazilian cinema lost a lot with the differences between these two important figures.

Let's return to the constitutive aspects of O pagador de promessas. Anselmo imagined an astonishing opening for the film. For this reason, from a sudden cut, drums, atabaques and ganzás emerge, musical instruments that place us in the presence of a candomblé ritual, something unheard of in national cinema at the time. Past depictions of candomblé in Brazilian cinema had only appeared in comedy scenes from films that romanticized the favela and African beliefs, as was usual in the chanchadas of Atlântida or Hebert Richers. The expressionistic lighting and the hypnotic sound of ritualistic chants reinforce the moment when we meet the central characters, Zé do Burro, a humble peasant, and his wife, Rosa. Then, adorned with Gabriel Migliori's beautiful soundtrack, which mixes classical notes with a berimbau9 arrangement, we see a visual narrative conceived to illustrate Zé's pilgrimage with his cross towards Salvador while the opening credits roll. It was not unusual, up until the 1980s, to find people who were paying their promises in the backlands of the Northeast of Brazil, paying off the most varied debts in some church in the extensive region of the country. This is something that is part of Brazilian culture. But through Anselmo's lens, Zé do Burro becomes the third-world Christ who will fight a battle of faith - and a bit of alienation - against the vicar of the Church of the Paço. As we know, Zé had promised to carry a cross as big and heavy as Christ's to the cathedral altar to honor the healing of his pet donkey, hit by a tree branch and wounded to death. The problem is that the promise had been made in a terreiro,10 not in a church. Although Brazilian syncretism recognizes the Orixá Iansã as Saint Barbara, a Christian entity, the priest of the Paço Church not only does not recognize the promise, but accuses Zé of heresy and prevents him from entering his church with the cross. The misfortune unfolds in such a way that soon the peasant becomes the target of an inquiry for agitation and disturbance, the local newspaper tries to fabricate a martyr unjustly accused by the church, and Rosa, so submissive to her husband, begins to have a love affair with a local pimp. This "butterfly effect" will culminate in the disgrace of all involved, proving that noisy clashes between opposing poles of morality and opinion are only harmful.

In the sequence in which Zé talks to the vicar and tells him his story, Anselmo exercises one of the innovative techniques among the many he has learned. He creates a long shot, traveling upwards, up stairs and through curves. From the gate to the last step of the staircase, the camera moves carefully, climbing the inclined path to the church door, only for us to be able to watch Father Olavo's opposition to the intentions of Zé. A handheld camera would be enough to make the journey, but let's remember that Anselmo, although immersed in the innovations of filmmaking language, was still a remnant of the old school, so that his tradition was mixed with the audacity of such a complex shot.

Another intense moment occurs when Zé watches a procession carrying an image of Santa Barbara arrive at the church. Again, Zé climbs the church stairs step by step, facing Santa Barbara, silently praying to the divinity, and begging her for a miraculous intervention. This sequence demonstrates Anselmo’s control of the creative decoupage in that the cuts of shots and counter shots give us the clear impression that the Saint is looking at Zé while Zé is begging to her. This is a contemplative, introspective moment, that reminds us of the work of Alain Resnais in Last Year at Marienbad, for example, but wisely avoids the use of voiceover to stimulate the audience even more as to the thoughts of the punished peasant.

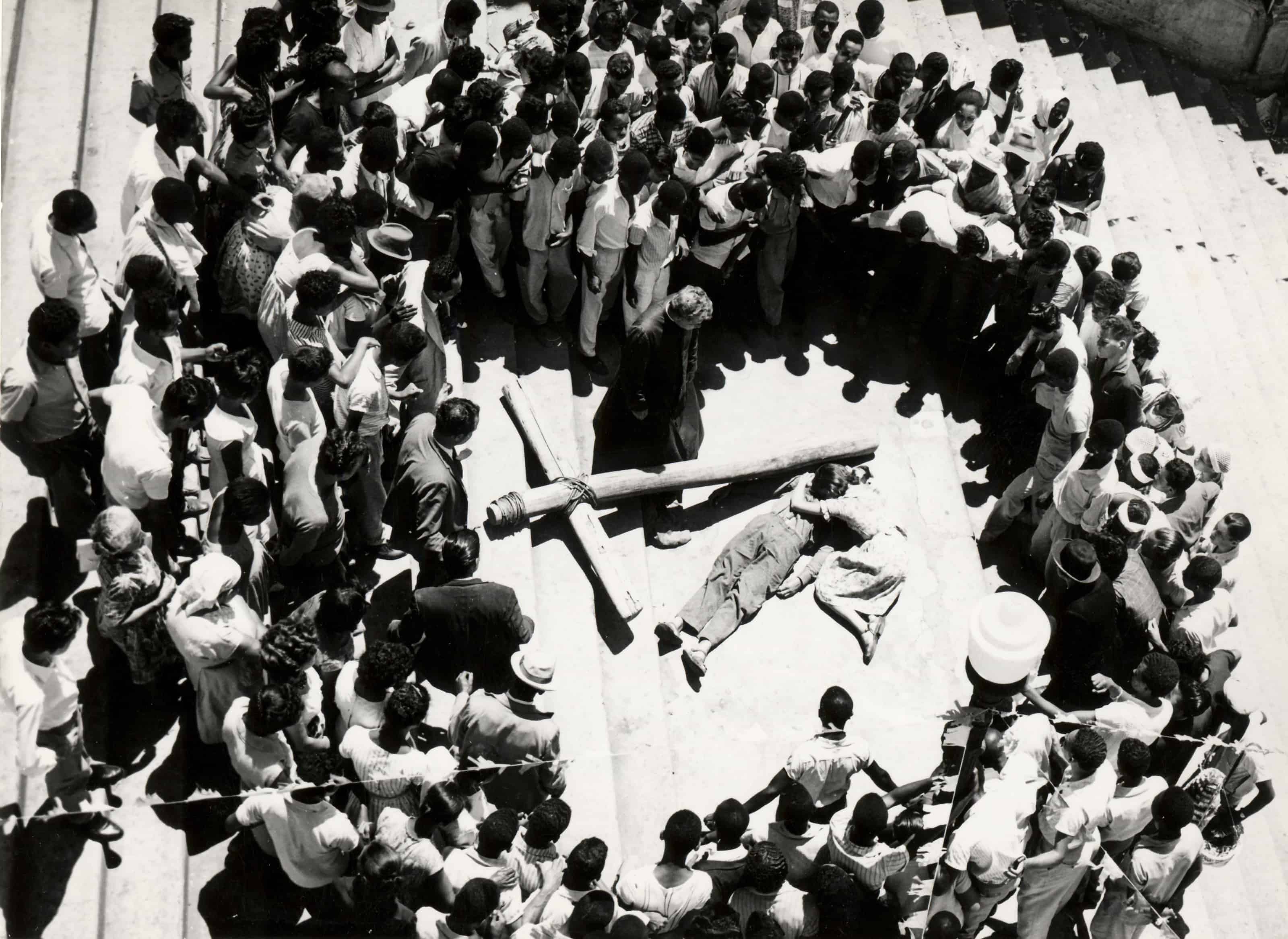

Another moment that expresses Anselmo Duarte's maturity as a director comes near the end of the film, when Zé, killed by shooting during a confusion at the church's doors, is placed on the cross that he himself had carried. While some of the crowd forcefully carries the cross into the temple of God, we have a shot in which the camera moves at a low ninety-degree angle upward, capturing the artifact as if it were hovering above us and floating towards the inside of the church. Technically, this scene required the crew to make some adaptations to the equipment, but the efforts were rewarded with an effect that had been uncommon since Mário Peixoto and Edgard Brasil practically invented national versions of cranes and rails to film Limite in 1930. And if we take into account that Limite was never commercially shown, Anselmo's solution may have been unprecedented in the eyes of the general audience.

There are many other moments of plastic beauty that combine the ancestry of a baroque setting and the inventiveness of modern cinema. This contrast would become a typical feature of Cinema Novo, in which aspects of a marginal and rough Brazil would be portrayed through a revolution of camera and narrative. Let's remember that Nelson Pereira dos Santos had already taken the first steps years earlier with the feature films Rio 40 graus (1955) and Rio Zona Norte (1957), approaching the inequalities of the then federal capital with eyes that were less overshadowed by colonial romanticism. Ruy Guerra also demystified the dazzled youth of Ipanema, Leblon and its surroundings with Os Cafajestes (1962) and soon Glauber Rocha would finish his Barravento (1962) and head for the backlands in search of the real cangaceiro, whom Lima Barreto had transformed into a John Wayne in his melodramatic fable produced by Vera Cruz, O Cangaceiro (1953).

III.

While Anselmo Duarte was carving out his social-religious tragedy, his country's cinema was preparing for an anthropophagic ritual in the best Oswaldian style,11 swallowing up what was new to return to a Brazil that was arid and straight to the point. The Palme d'Or that Anselmo brought back from Cannes in 1962 raised the thirst for the new, for the strange, and - for better or worse - for creative self-indulgence that produced some quite hermetic works and even sowed the seeds of fierce disputes in the name of vanity.

Anselmo himself declared that he was a victim of the aesthetic and ideological control that fell upon the national production after his award. If on one hand the filmmaker proved that a cinema of plastic quality and discursive depth was possible, on the other he became the target of those who considered him too old to be part of the new wave (although he was only 42 at the time). In fact, Anselmo fell into limbo at the intersections that he himself helped to create. Although an international award winner, the establishment considered him to be the product of an alienated era that was trying to reinvent itself at the expense of a culture that was not its own. An unprecedented error of judgment, but understandable when analyzed from a psychoanalytic perspective: you must kill your father to allow your own personality to emerge.

In his next work, Vereda da Salvação (1964), Anselmo Duarte would radically change his style, with looser long shots, naturalistic photography and a less linear narrative. However, he seemed to know that his new work would separate him even more from the new generation of colleagues. Brazilian critics didn't understand — or didn't want to understand — Vereda da Salvação. Anselmo felt the blows and became more and more withdrawn. His cinema became slow and, sometimes, lazy. The unfolding of his masterpiece was not worthy of the services he provided on behalf of a cinematography as callused and irregular as the Brazilian one.

However, when we watch the final shot of O pagador de promessas, in which Rosa cries alone outside the Igreja do Paço while a berimbau moans its mournful note, we are certain that Anselmo Duarte took the first step for the sertão to turn into the sea and the sea into the sertão, as the idealistic young artists of the following years would have wanted.

1. Cf. The imperialist option. Translated by Raian Oliveira. Rio de Janeiro, 1966. Original Title: A opção imperialista.

2. Cf. This world is a tambourine: the chanchada genre from Getúlio to JK. Translated by Raian Oliveira. São Paulo, 1989. Original title: Este mundo é um pandeiro: a chanchada de Getúlio a JK.

3. Starting in 1916, "naturais" composed newsreels, made and shown on a weekly basis, which kept film people busy shooting soccer matches, carnaval parades, parties, roads being built, ceremonies, factories, politicians, businessmen, etc. Many of their subjects were commissioned, mixing journalism and advertising. Hence the demeaning term "cavação", or swindling.

4. The term comedy of manners describes a genre of realistic, satirical comedy of the Restoration period that questions and comments upon the manners and social conventions of a greatly sophisticated, artificial society

5. SINGH Jr., Oséas. Goodbye Cinema: life and work of Anselmo Duarte, the most awarded actor and filmmaker of Brazilian cinema. Translated by Raian Oliveira. São Paulo, 1993, p. 68. Original title: Adeus Cinema: vida e obra de Anselmo Duarte, ator e cineasta mais premiado do cinema brasileiro

6. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs conducts Brazil's foreign relations with other countries. It is commonly referred to in Brazilian media and diplomatic jargon as Itamaraty, after the palace which houses the ministry.

7. Op. cit. p. 72.

8. Op. cit. p. 73.

9. The berimbau is a single-string percussion instrument, a musical bow, originally from Africa, that is now commonly used in Brazil.

10. A terreiro is a Candomblé house of worship

11. A reference to Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade.