Note: This article summarizes some of the ideas explored in my previous texts published in the books Plano Geral: Panorama histórico do cinema no Espírito Santo (Ed. Booklet/Sesc-ES, 2015) and Rasuras: 40 anos de vídeo experimental no Espírito Santo (Ed. Cousa, 2021).

Historians, archivists, and filmmakers who have worked to recover the historical records and memories of the cinema produced in Espírito Santo have discovered since its early days in the 1920s and throughout its history a fragmented, sometimes disjointed, and irregular path, alternating between isolated moments of production and larger periods of inactivity. This panorama stretched just over 60 years, until the 1990s, when a flow of audiovisual production gradually increased and diversified – initially with short and medium-length films, and, from the 2000s onwards, with a considerable amount of feature films. Given that the boom in film production is a recent scenario, we may look at filmmaking in Espírito Santo until the 1980s as a set of pioneering initiatives.

By compiling these early filmmaking experiences in this article, we reveal a film history that barely resembles the hegemonic historiography of Brazilian cinema. This may be explained by the economic and cultural particularities of the state of Espírito Santo throughout the 20th century as well as the scant access to technology for capturing and editing images within this period.

However, there are potential similarities between the case of Espírito Santo and other small Brazilian states who have an equally recent tradition of audiovisual production. These states have experienced an entirely different reality than the major centers that have determined the directions of the hegemonic histories that comprise Brazil’s national imaginary. Espírito Santo is a peripheral state in Brazil, corresponding to circa 2% of the country’s population and GDP. This is the case even though its per capita income is higher than the national average. The boost in urbanization, industrialization, and economic growth that the state has undergone has only occurred recently despite its proximity to major urban centers such as Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, and São Paulo.

The effects of this late urbanization process directly reverberated in the artistic production of Espírito Santo, which would only break away from academicism and fully experience modernity in the mid-1960s. Prior to this period, the literary, architectural, theatrical, and musical productions in the state that interacted with Brazilian modernism were far and few.

From this comes the predisposition of Espírito Santo for contemporaneity: we capixabas can assertively declare that we were never exactly modern, for when aesthetic modernity reached the local artistic class, finally synchronizing ourselves with the national artistic debate, we were already on the verge of transitioning to the next period. We were one step away from avidly plunging into the issues of contemporary art, postmodernity, peripheral globalization, cultural hybrids, and everything that came afterwards. Through a fragmented approach, this essay addresses some of the pioneering filmmaking experiences that set the stage for the flourishing Espírito Santo audiovisual production of the 1990s.

1. Ludovico Persici and his Guarany Device

The decade is the 1920s, in the early part of the last century. A driver exits a locomotive amidst smoke. He drags another man away from the railway tracks, crouching in front of the train as if posing for the camera. The setting is one of the Leopoldina Railway stations, on the stretch that connects the city of Cachoeiro de Itapemirim to Vitória, the state capital of Espírito Santo. The train soon departs, and from a window we witness a journey across the small and medium-sized towns in the southern region of the state. We also witness its landscapes and the small everyday events experienced by a family on vacation almost a century ago.

Such are the initial images of Cenas de Família, a silent short film by Ludovico Persici. Cenas de Família was filmed between 1926 and 1929 in the cities of Castelo and Cachoeiro de Itapemirim, and on the beach of Marataízes. The film contains some of the oldest moving images produced in Espírito Santo that have survived to this day.1

This family travelogue possibly contains the first footage filmed by Ludovico with his Guarany Device, an invention created in the same year in which these images were first registered. Also from 1926 is the only other known film by Ludovico, a western short-film called Bang Bang, shot in Conceição do Castelo and whose images are all but entirely lost today. Ludovico was perhaps the only active audiovisual director in Espírito Santo during the first half of the 20th century.

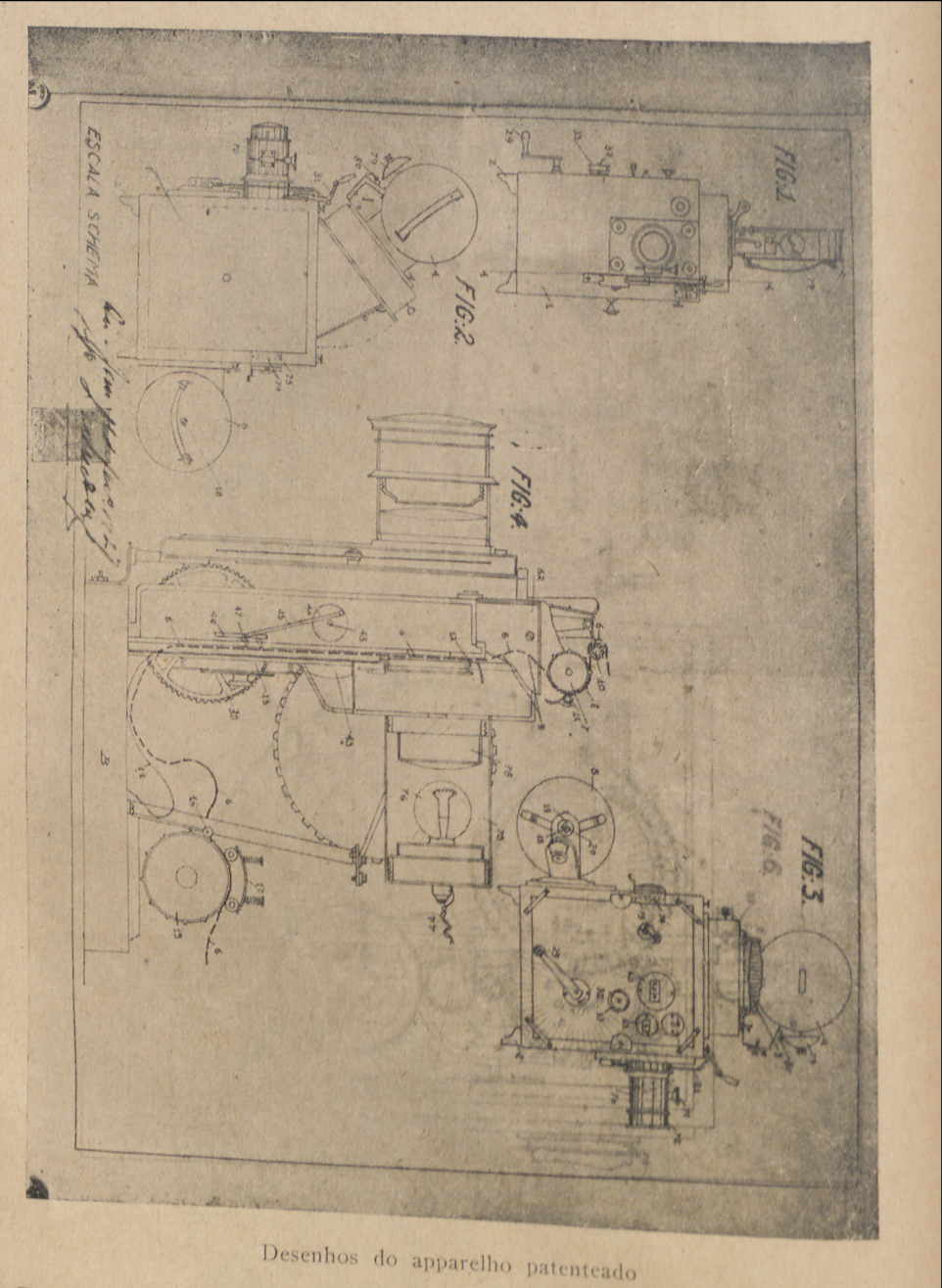

The son of a watchmaker, from whom he inherited the profession, Ludovico Persici was born in 1899 in Alfredo Chaves, a town in southern Espírito Santo. Since his childhood, Persici expressed an interest in assembling and dismounting mechanical devices to understand their inner workings. The contact with a traveling film exhibitor in 1908 as well as his work as a projectionist in the only cinema in the city of Castelo in the 1920s fueled his desire to build his own cinematographic equipment. From cans of butter and lenses that he himself developed, in 1926 Persici finished the Guarany Device – a machine capable of filming, projecting, copying, and measuring film, in addition to an attached bell which would ring and announce the end of the projection. Persici began to make his own films with this newly invented device. The films were then screened inside a shed behind his residence in Castelo, which served as an improvised theater.

It is impossible to specify how many works were produced by Ludovico, since most of this material has been lost. For a long time, it was believed that his only known film was Bang Bang. Cenas de Família was only discovered early this century after decades of resisting fungi and humidity inside poorly packaged plastic bags. The restored material was first publicly screened in 2008.

Some excerpts of Bang Bang were included in the documentary A máquinae o sonho, (1974) directed by Alex Viany, which portrays the life and work of the capixaba filmmaker and inventor. If Ludovico's name had been forgotten over the years, Viany's short film not only rekindled interest in his work, but also provided several pieces of relevant information, such as the fact that Bang Bang is the oldest western made in Brazil, long before the cycle of genre films produced between 1950 and 1960. Persici was behind the direction, script, and cinematography of Bang Bang.

In the following year, Persici patented his film camera invention in Rio de Janeiro. It was an innovative device as it combined the functions of many different machines. However, even with the partial support from the press at the time, he was unable to obtain sponsors for a large-scale production of his creation. This was due to the fragility of the national industry during that period. Additionally, the cinematographic field had not yet established itself in a market dominated by North American film productions.

After a short stay in Belo Horizonte, Persici returned to Espírito Santo in 1935, this time without the machine. The whereabouts of the machine have never been known. The early death of its inventor, victimized by tuberculosis in 1944, buried any possibility of ever finding it.

2. A Forty-Year Silence?

The first moving images made in Espírito Santo reveal a historical particularity. Produced in the mid-1920s, thirty years after the first Brazilian filmmaking activities, such images did not originate in the state capital, Vitória, but in smaller cities further south of the state. The economic development of Espírito Santo explains this phenomenon: while the state is in Brazil’s Southeast, the most developed region in the country and close to major urban centers, Espírito Santo did not experience tangible economic growth until the early 20th century. It was then that the expanding coffee economy in northern Rio de Janeiro reached the state’s southern region, mostly populated by Italian and German immigrants.

In addition to its predominantly agrarian economy (late industrialization would only arrive at the end of the 1960s), Espírito Santo had approximately 1.5% of the Brazilian population at the time, and its capital was still a very small city, with 22,000 inhabitants according to the 1920 Census. For comparison, Rio de Janeiro was 52 times larger 100 years ago and, presently, the Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro is 6.5 times larger than the Greater Vitória region. Some of the cities in the south of the State had between 40% and 60% of the capital's population, but the economic expansion at the time attracted some audiovisual activity to the region. Nevertheless, there is no record of a regional auteur-driven film cycle in Espírito Santo for almost 40 years after Ludovico Persici's films.

Even the first images taken in the city of Vitória in 1935 by the doctor Luiz Gonzáles Batan had no authorial intention and instead focused on registering everyday moments and the picturesque locations of the state city. Subsequent productions included occasional institutional or tourist documentaries produced by national public organizations during the Estado Novo regime (1937-1945) and newsreels from the 1950s by Júlio Monjardim, which mostly focused on registering government achievements. Nonetheless, during this period the capital of Espírito Santo had a population of 50,000 inhabitants and a considerable cinematic life. This is reflected both in the number of theaters and in the number of critics working in the local press, some of whom were responsible for the first film clubs, radio programs, and short courses dedicated to film language and culture in the state.

It is possible that lost home movies from this period exist; works produced by amateur or professional photographers from Espírito Santo and without any public screening records. These films may still be in the possession of family descendants, even if in poor conditions. However, the only somewhat preserved images with known public screenings are those made by Batan – which were compiled by his son Ramon Alvarado and projected in December 1967, during the I Amateur Film Festival during Cine Jandaia, in Vitória. In 1995, they were rereleased under the name Um belo dia – Vitória, 1935, which is the version currently available on Youtube.

3. The Amateur Cinema Cycle of the 1960s

The historical trajectory of Espírito Santo cinema underwent radical transformations after 1964. In fifteen years, the population of Vitória and its metropolitan area practically quadrupled, partly due to the late local industrialization and urbanization process. Furthermore, the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES), the local public university, consolidated itself as the new intellectual epicenter in the state of Espírito Santo, and the local youth was no longer forced to leave the state to continue their studies (although Rio de Janeiro remained a major reference point for the latest trends and customs). Hence, the city began to experience an intense and effervescent cultural scene, directly influenced by the countercultural and political movements that shook the country in that period.

“Repression during the dictatorship, the Arena Theater, Cinema Novo, Bossa Nova, surrealism, fantastic realism – a vast universe of influences in front of us: such was the state of Espírito Santo for us in the 1960s. No matter what you did – whether fighting in the streets against the rifle or baton, whether you wanted to be a filmmaker, actor, musician, or painter – life seemed to explode in a million directions, in an endless creative power. […] Camera in hand, theater in the square, poems emerging in the night-time bohemian life, graffiti against the dictatorship on the virgin walls, and the distribution of leaflets printed on Jurassic mimographers. That was how we lived in those years which today they call golden. Only then we didn't call them as such, we just had the privilege and the luck to live them”.

The testimony of Antônio Carlos Neves to Jeanne Bilich for the book As múltiplas trincheiras de Amylton de Almeida sheds light on the scenario in which young artists developed their creative processes in the inspiring years of the 1960s. The rise of a bohemian and combative generation, between melancholy and fine irony (especially as found in the chronicles of Carmélia Maria de Souza), gave new meaning to the melancholy brought by the customary south wind that blows on the island of Vitória, “Softly arriving and turning everything inside out” (in the words of the chronicler), and turned it into one of the most intense elements of its cultural identity. This young generation shared a series of political and aesthetic concerns which translated into heated discussions in film clubs, theaters, and art galleries (and even inside the Modern Art Museum, an independent and self-financed institution that existed in the city between 1966 and 1970). These discussions stretched until the break of dawn in legendary bars such as Dominó, Marrocos, and Britz Bar. In the world of music, ballroom dances gradually gave way to the mix of blues, jazz, and the rock of Os Mamíferos, a band founded in 1968 with high doses of surrealism and beat literature in their song lyrics.

Despite its short-lived existence, the MAM-ES had a very active film division which organized screenings of auteur films (especially European and North American classics) in the downtown area of the city. Other film clubs also attracted local moviegoers in the late 1960s. These include the Aliança Francesa film club, which brought many of the Nouvelle Vague novelties to the capixaba audience, and the Cineclube Alvorada, reopened in 1965 by Ramon Alvarado and Edgar Bastos and which focused on the most relevant productions in modern world cinema at the time.

The often-heated debates in Cineclube Alvorada prompted some of its regulars to nurture the desire to move on to practice and direct their own films, even if with limited financial resources. It was during one of these debates that Ramon Alvarado met Rubens Freitas Rocha, who owned a Paillard Bolex camera and rolls of 16mm film. From this meeting emerged the first fictional short film from Espírito Santo: Indecisão, concluded in August 1966 and directed by Ramon himself (and of which, unfortunately, a complete copy no longer exists).

Indecisão inaugurates an amateur film cycle in Espírito Santo which would only last a few years. However, it had significant reverberations in the local cultural scene. These were fictional short-films, many without direct sound and filmed in 16mm – the film gauge of movie clubs, since commercial cinemas used the 35mm format. Eleven films were completed in total (plus four unfinished films) between 1966 and 1971. These films were screened in film clubs and festivals inside and outside the state. Six directors emerged during this cycle: Ramon Alvarado, Rubens Freitas Rocha, Antônio Carlos Neves, Luiz Eduardo Lages, Paulo Torre, and Luiz Tadeu Teixeira.

Produced without any public funding and often paid for by the directors’ own resources and savings, these short films had very limited budgets, technicians and actors worked for free (often alternating roles from one film to another), and friends and family provided the locations and scene props. It is worth mentioning that most of the technical teams had a background in theater (Paulo Torre, Luiz Tadeu Teixeira, Milson Henriques), photography, visual arts, or even literature (Amylton de Almeida) – one exception being Antônio Carlos Neves, who studied at the University of Brasilia in one of the rare higher education film courses in Brazil at the time.

These productions used black and white negatives, borrowed cameras, and shot in natural light. The use of a handheld camera was common as well as close up shots of the characters’ faces. It was as if the filmmakers were trying to capture the intangible, yet suffocating and melancholic atmosphere of the period – such as in the famous close-up of actress Marlene Simonetti in Kaput (1967), by Paulo Torre, or the framed face in the vinyl insert of the Beatles album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, released that same year.

The short films were edited by the directors themselves, as if handcrafted. They used scissors, duct tape, and lampshades, rather than professional Moviolas. The first films of this cycle were silent, and even those with sound rarely had synchronized dialogues or off-screen voices; the soundtrack was extracted directly from the records that inspired this young generation: in Kaput, for example, we hear the songs “Mother's Little Helper” and “Lady Jane”, both by the Rolling Stones, during a lively party filmed inside the studio of the artist Marian Rabello. In turn, a stroll by the protagonists sways to the rhythm of a melancholic jazz tune, while the opening and closing credits are accompanied by Albinoni’s “Adagio”.

If, on the one hand, these films suffered from technical limitations, on the other hand, they overflowed with visual experimentation and a desire to convey not only the references that inspired their directors (particularly modern European cinema), but also the main political and social issues passionately debated by the intellectual left of the period. They are protest films against the struggles of their time, especially the repression of the early years of the military dictatorship. One example is the reference, in Kaput, to the so-called Suplicy Law, which prohibited political activities in student organizations and destabilized the national student movement. Heavily influenced by the trends of modern cinema, these directors created works from very personal points of view, in which the protagonists – who were perhaps a reflection of their own alter egos – were in permanent conflict between their ideals and the harshness of the outside world.

Hence, we find scenes such as the torture of the character portrayed by Milson Henriques on a pau de arara2 in Alto a la agresión (1967), or the newspaper article against the Vietnam War that costs the life of the politically engaged protagonist in Kaput. There is also the poet who, when confronted with the impossibility of writing a new poem, experiences the contrast between bohemian daydreams and the harsh social reality that surrounds him in O pêndulo (1967), by Ramon Alvarado. Equally significant are dilemmas that emerge from the romantic encounters between characters from different social classes, as takes place in Luiz Eduardo Lages' Palladium (1966) and Indecisão (1966).

We may also include in this list the dense symbolism permeating all scenes of Ponto e vírgula (1969), Luiz Tadeu Teixeira's debut film. A character tortures and smashes a cockroach while, at the same time, several doors close in front of another man in the most varied situations of his everyday life. The original version of the film was only one and a half minutes long, but in 1979 it was extended to five minutes with the inclusion of images from another film made by the filmmaker in 1971 and until then unfinished: Variações sobre um tema de Mayakovsky (inspired by the poem “At the Top of My voice” by the Russian writer). One of the scenes included in this version consists of a pantomime representing a seppuku, interpreted by Luiz Tadeu himself, expanding the metaphorical meaning from the original version of the short film.

Most of these productions had a clear destination: the amateur film festivals organized by Jornal do Brasil and sponsored by the department store Mesbla. During its six editions, held between 1965 and 1970, the festival revealed several emerging filmmakers who would change the history of Brazilian cinema in the following decades: Xavier de Oliveira, Antônio Calmon, Aloysio Raulino, Djalma Limongi Batista, Bruno Barreto, among others. This festival would also inspire subsequent film production cycles in other states which until then had a very limited film production.

Some films produced in the Amateur cinema cycle were also enrolled in the amateur film festivals in their respective years of production: the aforementioned Indecisão, Kaput, O pêndulo, Ponto e vírgula, and Alto a la agresión, as well as A queda (1966) by Paulo Torre and Veia Partida (1968) by Antônio Carlos Neves. The latter, as well as Alto a la agresión and Ponto e vírgula, were selected to be part of the festival program. Based on a short story by Amylton de Almeida about a problematic relationship between father and son, Veia partida won the award for Best Photography for Ramon Alvarado in the fourth edition of the JB/Mesbla Festival held in 1968 and was selected for a film event about Brazilian cinema held in Kiev that same year. Neves would then travel to the Soviet Union, on account of a scholarship at the Moscow Academy of Arts and Sciences. He would only return to Brazil 1974. In the same period, Luiz Eduardo Lages took up residence in Sweden, where he lives to this day.

Still without sponsors and invisible to the local government, the movement began to dissolve itself in 1968 after the AI-5 decree, which further hardened the military dictatorial regime in the years that followed. Alvarado moved to Rio de Janeiro to work professionally as a director of photography, occasionally returning to his native state to film some documentaries. Paulo Torre continued his career as a journalist, also in Rio de Janeiro, working in the mainstream media for a few years. Eventually, Torre returned to the state of Espírito Santo, where he served as editor in chief at A Gazeta, a position he held until his death in 1995. Upon returning to Brazil, Antonio Carlos Neves pursued a career in literature, theater, and audiovisual arts, having created the TV series Telecontos capixabas (1984-1985) for the public channel TVE Brasil, based on texts by local authors, and the hybrid documentary and fiction film-essay Esta ilha é uma… (1990). Luiz Tadeu Teixeira would continue to practice journalism in the following years and dedicate himself to theater. He resumed his filmmaking career in the 1990s with important short films such as O ciclo da paixão (2000) and Graçanaã (2005), maintaining the inventive and experimental essence of his early works.

4. The 1970s: Paradise in Hell?

Unfortunately, the consolidation of Espírito Santo’s industrialization during the 1970s had no direct effect on the local film scene, which remained practically suspended throughout the entire decade. That is not to say nothing was filmed on Espírito Santo soil during the period. Often with state-funded resources, a series of feature films were made by production companies from the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. These productions used local settings and extras but had little participation from local artists and technicians in their crew and cast.

These films included a roster of assorted works, ranging from auteur films such as Sagarana: o duelo (Thiago, 1973), which recreated Guimarães Rosa's backcountry universe in the capixaba landscape and represented Brazil in the official selection of the 1974 Berlin Festival, to very popular works such as the erotic comedy Quando as mulheres querem provas (MacDowell, 1975). There was also A vida de Jesus Cristo (Regattieri, 1971), a film based on the staging of the Passion of Christ in the city of São Roque do Canaã, in the state’s central region. In fact, Regattieri, who for many years directed the staging of the Passion of Christ, was the first citizen of Espírito Santo to direct a feature film (the only one of his career). It would go on to become the fourth highest grossing Brazilian film that year.

A lone exception in this period is the feature film Paraíso no inferno (1977) by Joel Barcellos. Best known as an actor and a household name in the films of Cinema Novo, the capixaba Barcellos returned to the state of Espírito Santo to conduct an authorial work with a team that included several names from the local cultural scene – including the musical group Mistura Fina, comprised of former members of Os Mamíferos. In telling the story of a young musician who refuses to sign a tempting musical contract, thus forsaking his promising popstar career to work for a mining company, the film often assumes an allegorical tone, a common trait of Brazilian auteur cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. The northern area of Vitória – with practically intact beaches, shortly before the proliferation of real estate speculation in the region – provides an idyllic backdrop to the scenery of the film.

In a sequence reminiscent of a music video, we see the destroyed shacks on the island waterfront to the theme of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, framed by the imposing Penha Convent, a colonial building on top of a mountain. Human heads, apparently beheaded, are spread out on a table alongside the heads of freshly caught fish, which in turn serve as a contrast to the grandiose machinery that extracts and transports iron ore. Between the monotony of freight trains sliding horizontally across the screen and the unpredictable oscillation of the small fishing boat in the Bay of Vitória, it’s as if we were witnessing the outbreak of hell in paradise, as constantly reflected in the incredulous lenses of the sunglasses worn by many of the film’s characters.

While there was a surge in Super-8 productions in several Brazilian states throughout this decade, authorial production with this format in Espírito Santo was very sporadic. However, there are records of an animated experiment, O rei do Ibes e outros experimentos (1977). This was a series of six 30-second stop-motion films by Mário Aguirre, Ricardo Conde, and Marco Antonio Neffa. There were also some fictional works directed by Sérgio Medeiros between 1977 and 1980. Medeiros created three short films and the feature film Sinais de fascismo (1980). Sinais de fascismo was inspired by the Argolas Case, a scheme for trafficking and grooming minors inside prison facilities. The film was illegally seized by DOPS officers during the opening screening at the UFES film club and was subsequently mangled with the removal of scenes that denounced the police officers involved in the aforementioned crimes. Sinais de fascismo would go over twenty years without another public screening.

Oblivious to the countercultural effervescence in the state capital, another fictional super-8 experiment took place within the western genre in the medium-length film Olho de gato (1975). The film was shot in the city of Pancas, in the northern mining region of Espírito Santo, due to its natural landscapes (reminiscent of the classic westerns) and the local tales involving gunslingers. The project was spearheaded by Rio de Janeiro watchmaker Ailton Claudino de Barros, who was responsible for the direction, and farmer and cinephile José Augusto Damaceno, the film’s protagonist. Damaceno narrates the story of a gold digger that stumbles upon a valuable stone, the cat's eye, and hides it on a farm, stirring the greed of the property owner. Ending with a duel in the vein of the classics of the genre, the film mobilized many of the town locals during its production. Unfortunately, this work has been missing for some years. An investigation into the whereabouts of the only remaining copy of the film is the focus of the documentary Olho de gatoperdido (2009) by Vitor Graize.

5. Orlando Bomfim: Mapping the Cultural Imaginaries of Espírito Santo

In the field of short and medium-length documentaries, Espírito Santo attracted a few productions from other states. These include Ticumbi (1977) by Eliseu Visconti, a film about the traditional cultural celebration in the town of Conceição da Barra, and Caso Ruschi (1977) by Teresa Trautman. Yet it was a project by a filmmaker from Minas Gerais that would ultimately change the history of audiovisual production in Espírito Santo. After Orlando Bomfim arrived in Santa Tereza in 1975 to document the memory of Italian immigration in Espírito Santo, he would go on to develop numuerous short and medium-length documentaries that gave visibility to several typical cultural expressions in the state. Bomfim not only mapped the representations of popular traditions, but granted them the means to present themselves to the audience with all their power and beauty. His films also denounced the core social problems of that time.

It all started when Orlando observed that even with the upcoming centenary celebrations for the Italian immigration in Brazil, the state of Espírito Santo was never mentioned in the national media. The filmmaker found that unacceptable, as the state had not only welcomed many immigrants in the past, but also preserved many customs and traditions of these immigrants, some of which had long since been lost in Italy. Two years of research and interviews resulted in the medium-length film Tutti, tutti, buona gente, propriamente buona (1976), which narrates the story of immigration in the state from the personal testimonies of their descendants. The film won the Humberto Mauro/Coruja de Ouro [Golden Owl] trophy for Best Documentary, awarded by Embrafilme. This was the most renowned award for Brazilian short films at the time.

The close contact with the cultural diversity of Espírito Santo prompted Orlando Bomfim to take up residence in Espírito Santo, which resulted in a sequence of six more documentaries in 35mm and 16mm format, made up until the mid-1980s. Three of his films were screened at the Brasília Festival in 1979: Canto para a liberdade – A festa do Ticumbi (1978), Augusto Ruschi Guainumbi (1979), and Itaúnas – Desastre ecológico (1979), winner in the documentary category of the competitive section that year. Also from this period is Mestre Pedro de Aurora – Pra ficar menos custoso (1978), a film about a jongo singer from the north of the state. In all these works, Orlando explored not only popular culture, but also environmental issues, whether in the work of biologist Augusto Ruschi in the preservation of orchids and hummingbirds or the historic city buried under the paradisiac dunes of Itaúnas. By rescuing the cultural roots of Espírito Santo, Orlando Bomfim significantly contributed to the appreciation and recognition of a cultural identity that mixes European, African, and Indigenous origins.

Orlando's interest in alterity translated into a refusal of the authoritarian voice of the off-screen narrator: Tutti, tutti, buona gente, propriamente buona, for example, entirely rejects this resource; in other films, the narration is limited to the bare minimum. The film thus establishes a communication in which the interviewee's discourse is rightly acknowledged, even if situated within the director's own discourse. The possibility of the “people” speaking in the film, according to Orlando, was part of a larger trend in Brazilian cinema that sought to reestablish dialogue with the population, now endowed with new voice after the revocation of Institutional Act Number Five (AI-5) in 1978.

Canto para liberdade, one of the most inventive films of this time period, prioritizes the viewpoint of the participants in the homonymous traditional staging. The film includes rare testimonies from researchers Hermógenes da Fonseca and Rogério Medeiros. The third and final act of the film presents a long sequence of images and sounds from the procession and chants of the annual Ticumbi celebration. Canto para liberdade alternates between photos of African individuals dressed in typical attire and images of a boatman who plays the role of king of the congo on his boat dressed in everyday clothes.

Dos Reis Magos dos Tupiniquins (1985) serves as the poetic synthesis of Bomfim’s process, as the film is a daring experiment in film editing. The short begins with images of the altar restoration in the Church of the Magi, built in the 16th and 17th centuries in the town of Nova Almeida. The opening also features the local traditional festivals, particularly the congo. Soon, the film presents a collage of images, sounds, newspaper clippings, and excerpts from literary works, which confront the history of Brazil from colonial times until the military dictatorship. Completed during the country’s redemocratization process, the film lays bare, during the looming euphoria provoked by the emergence of the New Republic, the myth of Brazilian cordiality from the contradiction between historical oppression processes (which have largely afflicted black and indigenous people) and democratic prospects, which, in the words of Kênia Freitas, “remain open-ended while mutually traversing, interrelating, accruing, and influencing each other” (Freitas, 66).

6. Where Are Those Noisy People?

During the same period as Orlando Bomfim Netto, a journalist and film critic named Amylton de Almeida directed television documentaries by utilizing the technical resources of TV Gazeta, a broadcasting channel that was operating in Espírito Santo in 1976.

The first documentary he made, São Sebastião dos Boêmios (1976), is one of the most important films in Espírito Santo’s audiovisual history. São Sebastião dos Boêmios portrays the daily life of the São Sebastião neighborhood (present-day Novo Horizonte in the town of Serra), at the time a prostitution district in the Greater Vitória area. The medium-length film brought forth elements that would become the filmmaker's trademark, merging an attentive gaze towards the margins of society with a powerful and witty social criticism. His following film, Os Pomeranos (1977), would win the 1st Globo Network Summer Festival, a competitive film festival comprising documentaries produced by affiliated broadcasters of the national Globo TV Network. Amylton would once again win the festival in its third edition in 1980 with O último quilombo (1980). Both documentaries were shown on national television as part of the award. By focusing on TV documentaries, Amylton de Almeida brought the urgent issues portrayed in his films to the public agenda, as reflected some years later with the enormous and controversial repercussion of Lugar de toda pobreza (1983), one of the central milestones of Espírito Santo cinema in the 1980s.

The orchestra and cannon shots from Tchaikovsky's “1812 Overture” echo fiercely. Instead of the customary fireworks and revelries, the images that follow are devastating: hundreds of people, mostly women and children, rush towards the garbage unloaded by trucks, fighting for space with vultures. Everything is scavenged amidst the debris, from rotting remains to hospital waste. Some, more daring, climb on top of moving vehicles in the hopes of collecting better-preserved items. Hands belonging to preschool children advance through the waste as they collect fruit or previously opened yogurt packages. In the final scene, a wide shot reveals hundreds of stilt houses along the mangrove, many of them accessible only by fragile wooden bridges. The caption finally reveals where we are: “São Pedro Neighborhood – Vitória, ES, 1983”.

This visual symphony, which does not shy away from its excessive tone and camp drama, plays out in the initial scenes of Lugar de toda pobreza (1983), a television documentary directed by Amylton de Almeida. In just over 50 minutes, this film portrays the everyday hardships endured by those living in the vicinity of the largest garbage dump in the Greater Vitória region at the time. The film features thousands of people trying to make their living from scavenging, salvaging, and occasionally reselling the items discarded by the rest of the city population. There are wooden shacks without running water or electricity in squatter settlements, some of them well-nigh buried in the debris piling up as high as the windows. From one of these windows, a mother, surrounded by two small children, lists for the camera the main demands of that brutally impoverished community.

The film takes place during the 1980s, when Brazil was undergoing a severe economic recession. Unemployment rates were soaring, aggravated by the still intense flight of Brazil’s rural populations to its major cities. At the same time, the Greater Vitória region was experiencing the continuation of major industrial projects from the previous decade such as the construction of large steel factories, and an increasingly intense urbanization and modernization process, especially in the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods.

The film abandons the typical voice-over narrator (a common trope in television documentaries of that time and in the filmmaker's previous works) to give voice to its protagonists. Out of the apparent chaos, a pattern gradually emerges as we understand the internal organization of this community led by the leader of the Waste Pickers Association, Mrs. Leda dos Santos. A woman reports on how her epileptic husband struggles to find a steady job while the camera frames the front of her shack, built on top of a rock, to emphasize a wooden sign that takes over half of a wall: “construction financed by the [public bank] Caixa Econômica Federal”. The exposure of this sign is an incisive ironic commentary by the camera, typical of Almeida’s works.

We also witness, in a moment of truce, the construction of new huts in the swampy terrain. The melancholic piano sound over the images provides some tenderness to those frail bodies as they struggle to balance wooden boards on their shoulders while crossing the dense waist-high mud of the mangrove. The use of a classical soundtrack, with a poignant melodramatic tone, attempts to snap the viewer out of their apathy by opposing the harshness of the images of life in the dump with well-known compositions from the classical repertoire. Songs include “Carmina Burana” by Carl Orff and even “Desapareceu um povo”, a very popular religious song in Pentecostal churches of the time, whose verses questioned: “Where are those noisy people / I see no brother of mine, where are they?”

The overwhelming impact that Lugar de toda pobreza had on public opinion after being screened on TV indicates that Almeida successfully provoked the middle-class viewer. While this strategy to shock the viewer may seem overtly sensationalist today, it emerged as the most feasible option at the time for a filmmaker with an extremely pessimistic view about Brazil's severe economic crisis. Hence the need to promote awareness about this issue to television audiences, introducing it on the public agenda in such a way that the intense reaction of the viewers practically forced public authorities to invest in infrastructure in the region – mostly from the end of the decade onwards. Orlando Bomfim and Amylton de Almeida’s social documentaries and mapping of capixaba culture paved the way for other filmmakers to embark on similar paths from the 1980s onwards. Prolific filmmakers Clóves Mendes and Ricardo Sá are great examples of this. They were constantly engaged in recovering traditional popular cultural expressions and calling attention to environmental issues while also, in the case of Ricardo, establishing direct contact with quilombola and indigenous communities.

7. Other People, Other Desires, Other Discourses: Pioneers in Experimental Video and Minority Cinemas

Amylton de Almeida was the first openly queer director in the state of Espírito Santo. While he did not directly explore LGBTQIA+ issues in his films, we find many layers of irony, camp drama/affectation, and disidentification (as defined by José Esteban Muñoz) in his works. There is a peculiar tone expressed not only in his documentaries, but also in his critical essays and in his only feature film, O Amor está no ar (1997), released posthumously and whose core aesthetic references are the queer melodramas of Sirk and Fassbinder. Amylton was a voice, therefore, that boldly deviated from the standard “white heterosexual middle-class man” which had defined almost all audiovisual experiences in Espírito Santo until then.

The trajectory of Espírito Santo cinema began to change with the 1980s generation, which explored video art at a time of political reopening, when official censorship was being relaxed. Additionally, in the 1980s there was the emergence of openly declared gender and sexual identities. Cultural collectives grew in college environments with conspicuous performative inclinations, such as Balão Mágico, Aedes Egypti, and Éden Dionisíaco do Brasil. Also, contemporary dance companies eager to explore the potential of video dance were created. Companies such as Canalhada and Neo-Iaô would find fertile ground in video art for their many aesthetic and micropolitical experiments stemming from the body as matter and sign.

Let us consider the elements found in the performance universe of Neo-Iaô, as higlighted by Marcelo Ferreira, one of the group's original founders: androgynous depictions, backward body movements referencing candomblé rituals, expressionist gestures, twisted hands and fists as if in negation, appropriations of Japanese Butoh, a fixed, catatonic face mask reminiscent of Munch's The Scream, which seems to blankly stare at nothing, and a corporal theatricality inspired by Grotowski and Artaud. The sum of these elements when transposed to visually exquisite static shots, sometimes approaching the body at sharp angles, sometimes at a distance while emphasizing the contorted human figure in an endless landscape, combined with the electroacoustic music of Jocy de Oliveira in the soundtrack, builds a thoroughly intense and hypnotic atmosphere which maximizes the potential of the performers before the camera.

In many of these groups, the expressive participation of women and LGBTQIA+ people, both collectively and individually, allowed for a greater diversity of perspectives, as well as the emergence of new themes. Many members of these groups would create their own individual films in the following decade, such as Rosana Paste, Saskia Sá, Luiza Lubiana, and Lobo Pasolini.

This 1980s generation conceived audiovisual expression as a perpetual process of artistic creation, a means of blurring the boundaries between life and art. These films conveyed a type of intellectual thought and methodology which have returned even stronger in recent audiovisual productions from Espírito Santo. These works are now traversed by issues of gender, race, sexuality, decoloniality, choreopolitics, and other bodily discourses found in the video performance works of extremely active artists in recent years, such as Rubiane Maia, Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro, and Fredone Fone.

One of the experimental landmarks of the period is the video artwork Graúna barroca (1989). The piece explores an artistic intervention by visual artist Ronaldo Barbosa on the virtually untouched natural landscapes of the Rio Negro beach, in the city of Fundão. The video uses elements from the region itself, such as tree trunks, sticks, algae, pigments, fire, and water. All of these elements are animated by the movements of nature in contrast to the widespread electronic animations by Brazilian video artists of the 1980s.

Ronaldo conceived his work as a living installation of colors and shapes soon to be destroyed by the sea, expanding on recurring elements from his previous drawings and paintings, such as horns, arrows, pitchforks, and other highly organic material symbols. Here, these elements elude two-dimensionality as a means of allowing the viewer to experience a three-dimensional space, but also to dialogue with rhythm, movement, and sounds in a dreamlike atmosphere. Reframed by human intervention, these elements are constantly reorganized in the visual composition by the camera movements as much as by the flow of nature itself. Graúna Barroca is one of the first video artworks created in Espírito Santo as well as one of the most awarded within Brazil and abroad, earning the Best Video Art award at the 33rd New York Film and TV Festival (1991), Best Experimental Video at the IV Rio Cine Festival (1990), Gold Medal at the Philadelphia Film Festival (1991), and the Special Merit Awards at the 15th Tokyo Video Festival - JVC (1992).

Ronaldo Barbosa later established a partnership with Arlindo Castro to create TV reciclada (1992). A hybrid between video art and essay documentary, the medium-length film questions the role that television plays in the contemporary social imaginary, as well as its attempt to build its own worlds, privileging audience reception as essential to promote a less passive relationship towards television content. Castro was responsible for the script, which incorporates visual gags and sketches imbued with computer graphics and editing effects – some designed by Hans Donner, to whom Arlindo was very close, and others designed by Eric Altit. All these elements are linked together in a non-linear narrative flow, typical of Brazilian video productions of that time. The video constantly plays with the language of television, especially news programs, quiz shows, and videography, providing multiple answers to the question: “What is television?”. Many of the answers have an ironic tone, such as in the initial sequence when a television is removed from a butcher’s shop, as if it was a piece of meat soon to be sold in a supermarket. In another scene, a final prayer is uttered on a church altar where an out of sync TV has replaced a sacred statuette and nearby parishioners are crying out for the promise of “another life, much better than ours.” Then, in the following sequence, a couple watches crackling flames broadcasted by a television set which has been placed inside an empty fireplace in the living room of a tropical upper-middle class home – an ironic precursor to the contemporary electronic fireplace, a dream item in home decor TV shows in northern hemisphere countries.

Arlindo Castro has been a unique figure in the Espírito Santo cultural scene since the late 1960s. He was the second Black filmmaker to work in Espírito Santo – preceded by Gelson Santana, who directed the surrealist short-film A miragem das fontes in 1990, shot in Rio de Janeiro and financed by the Espírito Santo state government. Arlindo’s artistic origins are in the fields of literature and music (a former member of Mistura Fina, a musical group with a role in the feature film Paraíso no inferno). In the following decades, he devoted himself to teaching and theoretical research in the field of image studies and went on to become a renowned audiovisual scholar in the Brazilian scene at the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Arlindo has explored many different issues in his articles, including videography, reception studies, Brazilian representations in foreign films, and a critical and cultural approach to television. His doctoral dissertation at New York University, Films about television, although still unpublished in book format (Arlindo died prematurely in 1997, four years after concluding it), is one of the rare Brazilian-authored texts quoted in Robert Stam’s book Film Theory: An Introduction, a reference work in the historical mapping of audiovisual theory. His theoretical exploration of television strayed from a simplistic, black-and-white approach to the issue, quite common in the Brazilian intellectual milieu of the time, as he sought a non-paternalistic conception of the viewer to reflect upon their broader relationship with television. TV reciclada provides a practical development to this approach, with a non-reductionist gaze that is constantly attentive to the ambiguous relationship between viewers and the media.

If the first Black filmmakers residing in Espírito Santo would only make their directorial debuts in the early 1990s, the presence of women behind the camera began slowly in the previous decade, by way of television documentaries produced by TVE (with the work of Tida Barbarioli and Gerusa Conti) or independent works by filmmakers such as Valentina Krupinova. Furthermore, the collective performance works by Éden Dionisíaco do Brasil were created solely with the collaboration of women. It was only in 1992 that the directors of this generation began to author solo works, such as the documentaries Moda (Saskia Sá, 1993), A Lira Mateense, and a musicalidade de um povo (1994), the latter two created by Margarete Taqueti, who emerged from the film club movement of the previous decades. There is also the work of experimental fiction Sacramento (1992), created by Luiza Lubiana in partnership with Ricardo Sá, who filmed in Super-8 and then finished in U-Matic video. Sacramento is a reinterpretation of the myth of Saint Sebastian, rescued by a priestess who washes his injuries in the river waters. The short film is set in a dreamlike universe, inhabited by archetypes that take us back to immemorial times, through a cinematographic language that Luiza would later explore in her fictional films A lenda de Proitner (1995) or the feature film Punhal (2015), the first directed by a woman in Espírito Santo.

From the 1990s onward, audiovisual production in Espírito Santo entered a new phase, shedding its intermittent character and becoming continuous, due in part to the public funding mechanisms that emerged during that period. In the years that followed, the profile of filmmakers in Espírito Santo gradually diversified, with an increasing participation of women, Black, Indigenous and LGBT creators, and, in the twenty-first century, of trans and quilombola people as well. If this cinematography was only able to include these other subjects of discourse after more than sixty years of existence — and more intensively over the last ten years—the present moment points toward an increasingly diverse and compelling panorama.

Nevertheless, much remains to be done in the fields of criticism, preservation and dissemination, and historiography. There is an urgent need to recover a number of pioneering works that currently have no copies available for circulation—such as, for example, the films made by the first women filmmakers from Espírito Santo, which were only briefly mentioned in this text precisely because access to these materials is nearly impossible, making it unfeasible to carry out adequate aesthetic and discursive analyses. The absence of a Cinematheque or a Museum of Image and Sound dedicated to local production also hinders the creation of a centralized, publicly accessible collection, as well as the systematic promotion of restoration and digitization initiatives for copies of historical and cultural importance to the state’s filmography—something that occurred for a very brief period under the State Government (and which enabled the restoration of a film by Ludovico Persici) and, more recently, through independent initiatives such as those led by Pique-Bandeira Filmes. The recovery and dissemination of these materials is becoming increasingly urgent, so that future generations may have broad access to these images, which engage with, provoke, and continually feed our reality, our culture, our concerns, and our imaginaries—and so that texts like this one do not one day sound like a kind of requiem dedicated to a series of pioneering works that may otherwise be lost over time.

1. The other being an institutional documentary from 1926 which portrays a rural school in Veado (present-day Guaçuí).

2. Pau de Arara is a designation given in the Northeast Brazil to a flat bed truck adapted for passenger transportation. The truck's bed is equipped with narrow wooden benches and a canvas canopy.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

BILICH, Jeanne. As múltiplas trincheiras de Amylton de Almeida: o cinema como mundo, a arte como universo. Vitória: GSA Gráfica e Editora, 2005.

BRAVIN, Patrícia. O Apparelho Guarany e o primeiro cinema no Espírito Santo. In: OSÓRIO, Carla (Org.). Catálogo de filmes: 81 anos de cinema no Espírito Santo. Vitória: ABD&C/ES, 2007.

FREITAS, Kênia. Liberdade em construção. In: DIEUZEIDE, Maria Inês e GRAIZE, Vitor (org.) Imagens para a liberdade: Retrospectiva Orlando Bomfim, netto. Vitória: Centro Cultural Sesc-Glória, 2018.

HENRIQUES, Milson. Geração 60 e o movimento do cinema amador. In: OSÓRIO, Carla (Org.). Catálogo de filmes: 81 anos de cinema no Espírito Santo. Vitória: ABD&C/ES, 2007.

TATAGIBA, Fernando. História do cinema capixaba. Vitória: PMV, 1988.TEIXEIRA, Luiz Tadeu. Para quem tem olhos para ver: o cinema no Espírito Santo. Escritos de Vitória, v. 22 – Cine Vídeo. Vitória: Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, 2002.