Salvador: 1950s-1960s

Despite all the improvements in the methodology of historical research related to film history, it has become common for approaches to cling to certain biases, whether thematically or spatially, which shape the way historical processes are interpreted. With Brazilian cinema, this has been no different. Even though Jean Claude Bernardet questioned founding myths in the 1990s, we seem to still believe them. We continue to establish hierarchizing causality relations which may hinder us from developing new points of view when writing about the history of Brazilian film. As a result, objects and subjects which could be considered more central in the canon by researchers become “blindspots”.

There are many examples, but in this text we will focus on the filmography made in the state of Bahia during the 1950s and 1960s. Part of it, such as the films of Alexandre Robatto Filho, remains relatively unknown,1 while other films, especially those made between 1959 and 1964, are considered nothing but a path to the Cinema Novo movement. This is mainly due to the presence of Glauber Rocha.

The period between 1959 and 1964 is referred to as “the Bahian cycle”, the name emphasizes the ephemeral nature of Brazilian film production, especially those works that were not produced in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. This period is also referred to as the “Bahian New Wave”, which stresses its connection to New Cinemas that were developing around that time, mainly in Europe. The Bahian cycle took place in Salvador, Bahia’s capital city, effectively inscribing it in a context of intense intellectual and artistic production, not only with respect to film, but also visual arts, literature, music, theater, and even the structure of daily college life, with the creation of the University of Bahia.

We should also stress the importance of the creation of the Clube de Cinema da Bahia (Bahia Film Club) in 1950, spearheaded by film critic and lawyer Walter da Silveira, who also became its programmer. The existence of this film club made it possible for the Bahian film scene to organize, and, according to Veruska Silva, from then on Salvador saw the...

...formation of a sensibility to reflection and/or participating in implemented or desired change, which made it a singular, memorable experience for so many people. It was also at the Clube de Cinema that the possibility of making film a vehicle for thought, expression, creativity and work became a concrete option for many cultural agents in Salvador (2010, p. 48).

Between 1959 and 1964, fifteen films were made in Bahia. In many ways, filmmakers were searching to present images on screen that were deemed fundamental to Bahian culture and society.2 During this period, there was an ongoing debate about what these features precisely were in the fields of the social sciences and arts, reflecting how filmmakers, intellectuals, visual artists and writers systematically cared about issues related to Bahia’s cultural formation.

We can point to literary works during this time period such as those by João Ubaldo Ribeiro, Adonias Filho, Sônia Coutinho, in addition to Jorge Amado (who had been writing since the 1930s) which look closely at the daily lives of common folk via characters who were fishermen, prostitutes, street urchins, dock workers, yalorixás, market traders, union men, Native Brazilians, and poor black, white and mestizo people. In addition, since the 1950s, Milton Santos, Thales de Azevedo and Vivaldo da Costa Lima had been conducting research about Bahian society. They observed, among other issues, the complexity of racial relations and social hierarchies in a state with a predominantly black population.

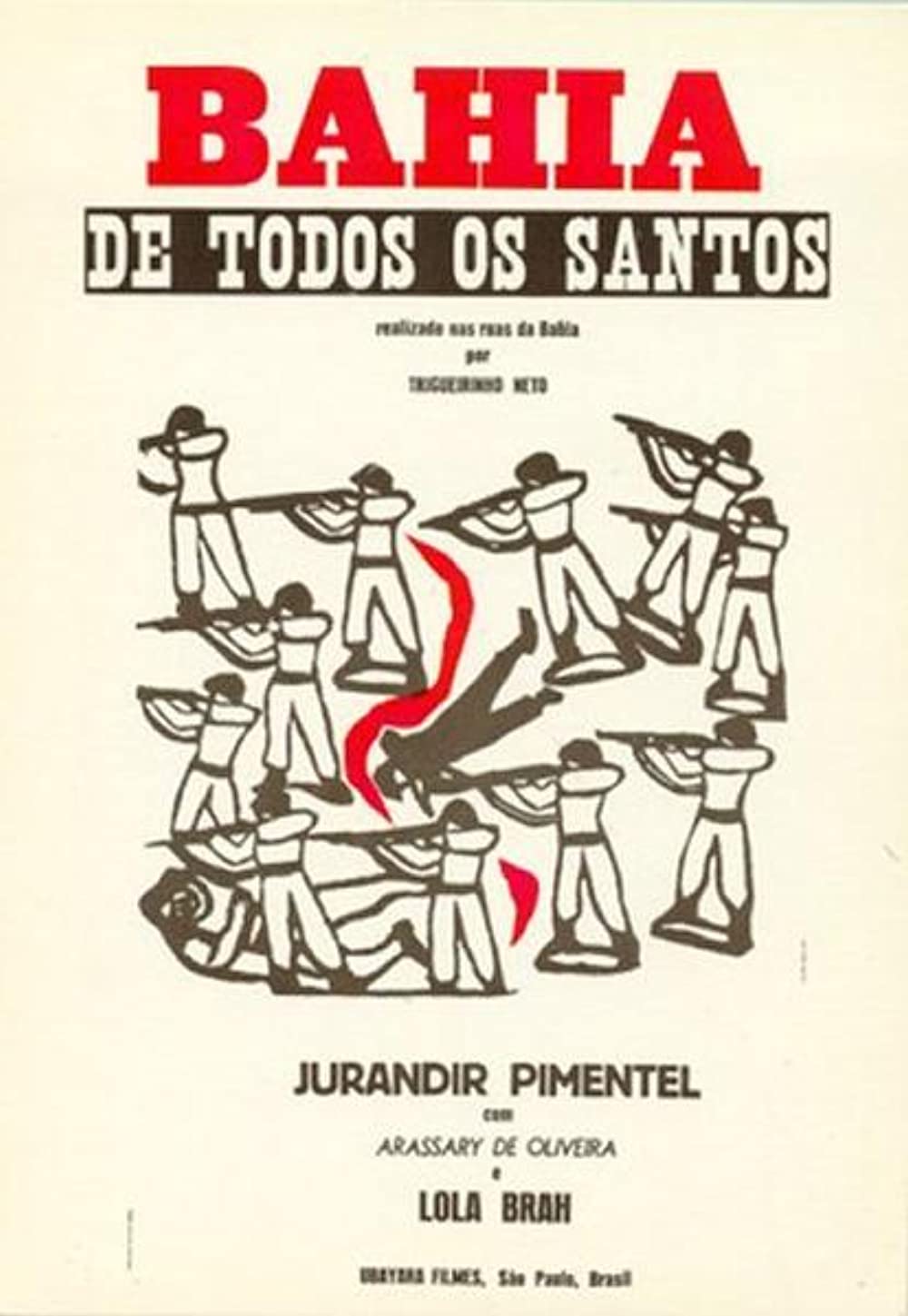

Lastly, Mário Cravo Jr, Pierre Verger, Carybé and Rubem Valentim dealt with the aesthetic impact of Afro-Brazilian religions, creating a new visual identity based on these new references, re-signified in the visual arts. There were also the incursions of architect Lina Bo Bardi working on the Museu de Arte Popular da Bahia (Bahia Popular Art Museum) and the Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia (Bahia Museum of Modern Art) which shared that interest, as hinted by their very names. It is within this cultural melting pot that we can locate filmmakers, artists, and intellectuals from Bahia and other parts of Brazil, and also Trigueirinho Neto and his film Bahia de todos os santos (1961).

Bahia de todos os santos, the Disenchantment of Bahia

On June 30, 1959 Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes wrote a letter of introduction for Trigueirinho Neto to Walter da Silveira, in which he briefly mentioned Trigueirinho’s interest in shooting a film in Bahia, as well as his formation in Rome’s Experimental Film Centre. According to Maria do Socorro Carvalho, Trigueirinho was in Salvador since February, working on Bahia de todos os santos, but he was initially seen with suspicion by Bahian filmmakers (2002, page 100). However, this changed after the local filmmaking community had the opportunity to see his (now lost) short Nasce um mercado at the Bahia Film Club.

From then on, his upcoming film was met with high expectations. Between November 1959 and February 1960, the production caught the attention of film critics and the Bahian film scene. By then, Redenção (1959), Pátio (1959) and Um dia na rampa (1960) had already been completed and shown publicly.

In the guise of a preamble, the opening credits of Trigueirinho’s film are imposed on a map of Bahia highlighting the Bay of All Saints (Baía de Todos os Santos), a geographical accident around which Salvador and the Recôncavo Baiano region were settled. As it was one of the first regions to be occupied in colonial times, to this day the Bay accounts for the most common images used to identify Salvador - the blue sea, the Lacerda elevator, the ramp of the Mercado Modelo, the houses of the old downtown region and the mostly black population walking around. It is also where a significant portion of the film takes place.

Following the map, but still during the opening credits, we see many schooners tied to the shore at the ramp of Mercado Modelo and workers unloading the merchandise brought from towns all over the Recôncavo onto the street markets. This is a fictional film, but those two opening minutes are imbued with a documentary quality which directly relates Bahia de todos os santos to Luiz Paulino dos Santos’ documentary Um dia na rampa, a film about a day in the life of workers at that same location. That very environment, with intense circulation of goods and people, is where we first meet our protagonist Tônio (Jurandir Pimentel). Skinny, shirtless and sitting on a barrel, seemingly oblivious to the world around him, he conveys his anguish and relative isolation due to his racial and economic situation. Then, he notices the presence of a well-dressed man in a light suit and carrying a pocket watch. So, he follows the man and steals his watch, bringing an end to the preamble.

From then on, we follow Tônio as he walks through the Comércio neighborhood (which is undergoing a renovation) and a cut takes us to an unspecified beach where he meets his friends, Pitanga (Antônio Sampaio), Manuel (Geraldo Del Rey), Matias (Eduardo Waddington), Neco (Francisco Contreiras) and Crispim (probably Nelson Lana). It is on this beach that they hide from the police, receive and handle smuggled goods, and assess the outcomes of petty thefts. Sitting there on the sand, they discuss for the first time themes that are important throughout the film: the hardships and limitations of living in an impoverished city, the fact that job opportunities are often relegated to those with the right connections, and their desire to go down to Southwest Brazil in the hopes of finding better life conditions.

Not much later, far from downtown Salvador, we are amongst dunes and coconut trees, an image that is recurring in Alexandre Robatto Filho’s films Entre o Mar e o Tendal (1953) and Xaréu (1954). There, a mounted police troop swiftly rides to a fishing community, right when a Candomblé ceremony is taking place. The policemen, still on horseback, stampede toward the population, destroying the pejís where the symbols of the orixás were placed, set fire to the house, threaten to arrest the yalorixá, Mother Sabina, and force the women to carry what is left of the religious symbols to a police post, in a sort of funeral parade which goes by Tônio as he makes his way to the village.

With Tônio's arrival, we find out that Mother Sabina is his paternal grandmother, that his mother is sick, and that his father has abandoned them. Even though Tônio wants to get closer to both mothers, the two women shun him, as if he didn’t belong there. This is the reason for his isolation - being a mestizo, he is too white for his mother and grandmother, and too black for any scarce job opportunities the city has to offer. Lacking a permanent home, he spends his time at Pitanga’s mother's house, the apartment of an Englishwoman (a foreigner with whom he has a turbulent affair), in Neco and Alice’s (Arassary de Oliveira) room, or at the beach hideout.

Even though all the characters besides Tônio have family or acquaintances to turn to, the film mainly takes place on the streets. Whether they are strolling on the beach or on downtown streets, around the Pelourinho, going to bars, making agreements, fighting or running away - the streets are the stage of everything in the lives of these young men. But the city we see in Bahia de Todos os Santos is the opposite of the postcard image. It is a decadent, impoverished Salvador, oppressive to its working class, which consists mostly of poor black people - as exemplified not only by the main characters, but especially the extras who we see at parties, in union meetings, in jail, or in the reformatory.

In one of Tônio’s visits to Pitanga’s mother, there is a dialogue regarding a strike at the docks in which Pedro, Pitanga’s brother, is involved. Pedro is killed after shooting a police officer at the strike, and because Pitanga tries to help him fight the police, he now needs to go into hiding. Tônio steals some money from the Englishwoman to help in the escape of the union men, who successfully flee when the police forcibly end the strike. When Tônio breaks up with the Englishwoman, she turns him in to the police. He is arrested but refuses to tell on the fugitives. It is important to stress that the persecution of Mother Sabina’s Candomblé house and the dockworkers’ struggle to unionize are hints that the film takes place during the Estado Novo (1937-1945), as we see in the first scene that the film is set “a few years ago”.

At that point in the film, there are hints that the group of bandits is going to dissolve. Although at first everyone seems worried, only Manuel insists on helping Tônio. Neco and Alice go to São Paulo. Crispim, relatively established as a visual artist, goes to study in Rio de Janeiro after receiving a recommendation. Matias disappears after Neco catches him in bed with Alice, and Manuel is going to marry his pregnant girlfriend. Finally, Tônio is released after an intervention from his grandmother. She is upset that, on top of being harassed by the police due to the Candomblé house, she is going to have to serve as a guardian for Tônio, who ends up in the same place he started: the ramp of Mercado Modelo, in anguish and isolated, gazing at the horizon.

Although aiming for a balanced perspective - with the presence of both black and white characters, Trigueirinho’s screenplay and public declarations about the film border on the fallacy of “racial democracy”. Racial tension and inequality are key elements in the film and they impact the fates of each character, countering the filmmaker’s declarations. When Crispim, a white man, says “this talk of color is nonsense”, Tônio retorts “if you went there, you’d get a job in no time. With me it’d be a different story. They say everything is easy, everything will work out, skin color won’t get in the way. But that’s not true. Just ask us.” And, regarding the Englishwoman, “She likes my color. They despise and loathe us, but in bed we’re good enough. Every white woman says they do it to help us, to save us. The Englishwoman always tells me that. You wouldn’t understand. You’re white.”

While Crispim, Manuel, and Neco - all three white - are able to plan their futures, black characters are left without any possibilities. Pitanga has to run from the police. Tônio and Mother Sabina, his grandmother, are left with the constant threat of imprisonment and the frequent racist, dehumanizing humiliation at the hands of the police chief. Even though she refuses to bow down, that is not enough to counter the aggression. So, the film “betrays” its maker, as it stresses the opposite of his intended perspective by showing the impossibility, even in fiction, of equality between white and black people in a racist society, and also by the refusal of Bahians to identify with the film - which was made explicit at its first public showing.

“Frustration, mercy, and revolt”: The Reception of Bahia de Todos os Santos in Salvador

As stated before, the initial suspicion of Trigueirinho and his cinematographic intentions in Salvador was reversed when his first film was shown at the Bahia Film Club, which earned him a warm welcome by the film scene, as evident in the article Para Trigueirinho Neto, um louvor [In praise of Trigueirinho Neto], written by Walter da Silveira for the Diário de Notícias newspaper in September, 1960. In it, the critic offers a brief retrospective of Bahian cinema, in order to insert Trigueirinho’s arrival in the context of effervescence and mobilization of 1959/1960, citing Roberto Pires, Luiz Paulino dos Santos, Glauber Rocha and the desire to make films with local themes and issues, as would be the case with Bahia de todos os santos and Barravento (1962) - being produced at the time - and repudiating the French and German films which utilized the city and its people as mere background.

With that in mind, we can understand the expectations around Bahia de todos os santos, which, according to Maria do Socorro Carvalho, was reinforced by the filmmaker’s statements, describing it as “a film about the people, for the people, telling its story linearly, with simple dialogue and making use of popular music” (2002, page 100). In addition to the attention of film critics, around the time of release there was intense press coverage, which created a general interest for the film.

However, even though the premiere was a major event, with the presence of film critics, the cast, politicians and the general public, the rejection of the film was proportional to the expectations. Contrary to what Glauber Rocha had pictured in his praise of it, the dismissal came mainly from the audience. During the session, they booed the film, as they didn’t identify with what Trigueirinho claimed to be its target audience nor with the city portrayed in its contradictions.

As for the critics, Walter da Silveira, in his second article dedicated to the film, Com sinceridade, para Trigueirinho Neto [Sincerely, to Trigueirinho Neto], published in Diário de Notícias on September 25 and 26, 1960, was the first to issue his disappointment with what he had seen. Silveira criticized the film’s rhythm, fragmentation, discontinuity and “lack of Bahian temperament”, as well as “lack of artistic humility” or “artistic conscience” by the filmmaker, as he underestimated the criticism he’d received and - in Silveira’s opinion - wrongfully used the idea of avant-garde to shield himself from the incomprehension of the audience. It’s probable that such a harsh stance was motivated by Silveira’s position as “dean” of the Bahian film scene, which may have caused younger critics, such as Orlando Senna and Hamilton Correia, to not take part in the controversy around the film, even though they recognized it as an important work.

Glauber Rocha, on the other hand, directly defended the film, in the article Defesa do filme [A defense of the film], published in Diário de Notícias on October 2 and 3, 1960, making use of Neorealist ideas to defend Trigueirinho’s choices. According to Carvalho (2020, p. 111), Glauber’s piece was a response to Silveira’s stance, stressing the qualities of the film, as did Roberto Pires from a different perspective, when he pointed out the importance of the acting of Antônio Luis Sampaio, who would later incorporate the name of his character into his stage name, Antônio Pitanga.

Lastly, as we look at the relationship between the images in Bahia de todos os santos and the aforementioned films by Luiz Paulino dos Santos and Alexandre Robatto, we are open to a comparative approach which might deepen the discourse of film with the mystic regarding the state of Bahia, especially when it comes to Salvador - which also involves visual arts and music. Then we can understand the overwhelming rejection to the film upon its release, despite the fact that it posed significant issues which were close to modern cinema, such as social and political matters. During the 1950s and 1960s, the context of artistic, cultural and intellectual production and reflection helped shape what we recognize as “aspects of Bahia” well beyond the state’s borders. And it seems to us Bahia de Todos os Santos played a key role in that process.

REFERENCES

BERNARDET, Jean Claude. Historiografia Clássica do Cinema Brasileiro: metodologia e pedagogia. 1ªedição.São Paulo: Annablume, 1995.

CARVALHO, Maria do Socorro. A nova onda baiana: cinema na Bahia (1958-1962). Salvador: EDUFBA, 2002.

GUSMÃO, Milene de Cássia Silveira. Dinâmicas do cinema no Brasil e na Bahia: trajetórias e práticas do século XX ao XXI. Tese de Doutorado. Universidade Federal da Bahia, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Sociais: Salvador, 2007.

NOGUEIRA, Cyntia (org). Walter da Silveira e o cinema moderno no Brasil: críticas, artigos, cartas, documentos. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2020.

RUBINO, Silvana e GRINOVER, Marina (orgs). Lina por escrito. Textos escolhidos de Lina Bo Bardi. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2009.

SETARO, André. Panorama do cinema baiano. 2ªedição. Salvador. EGBA.

SILVA, Veruska Anacirema da. Memória e cultura: cinema e aprendizado de cineclubistas baianos dos anos 1950. Dissertação de Mestrado. Programa de Pós Graduação em Memória: Linguagem e Sociedade. Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste: Vitória da Conquista, 2010.

STAM, Robert. Multiculturalismo tropical: uma história comparativa da raça na cultura e no cinema brasileiros. São Paulo: EDUSP, 2008.