If one truly wants to grasp the complex and numerous ways in which Black authorship has manifested itself in Brazilian cinema, exploring short films is an imperative towards gaining a qualified understanding. During the first six months of 2018, I extensively researched this topic and went on to curate the largest film retrospective centered around the presence of Black directors in Brazilian cinema, titled Black Brazilian Cinema: Episodes of a Fragmented History. The retrospective was hosted at Belo Horizonte International Film Festival and twenty-five short films spanning from 1973 to 2018 were screened*.

The constellation of films that you’re about to navigate through directly results from this research, but also bears influence from the nearly 14 years that I’ve been working with film. The function of this constellation is to provide an introduction to a history for an international audience. However, the films collected below do not make up a definitive or all-encompassing account of Black authorship in Brazilian cinema. One article can’t reverse the decades of disregard towards these films. In order to combat the constant fragmentation of our history as Black people in cinema, we need long-term action from multiple players, including those within the world of Film Studies, who, in Brazil, remain stubbornly inattentive to these films.

Many further factors limit the reach of this constellation. For example, preservation is a major issue. The short films of Waldir Onofre, Adelia Sampaio, Afranio Vital, and many other pioneers of Black Brazilian cinema are either permanently lost or are very difficult to access. I’ve also prioritized films that were produced with the original intent of being circulated in cinemas and film festivals. Therefore, I’ve not included the short films of Joel Zito Araújo, a key Black voice in the feature film format, because they are closer to journalistic paradigms rather than cinematic. This explains why some of my favorite contemporary filmmakers – Lorran Dias, Jessica Queiroz, Bruno Ribeiro, Ana Júlia Trávia, Asaph Luccas, Gleba do Pêssego collective, and the “Perifericu”’s directors: Nay Mendl, Rosa Caldeira, Stheffany Fernanda and Vita Pereira – are also not included within the constellation, but I encourage you to explore their work.

Enough said. Buckle your seatbelts and enjoy the journey.

* For more on the retrospective, please refer to the 375-page bilingual catalogue produced by the festival, available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1tYxGjUA-mCO4lfO6GRKcp9g1Mo3Jx0s0/view

DAWN (2018)

One of the most meticulous filmmakers of her generation, the films of Everlane Moraes constantly broaden our perceptions of what documentary cinema can be. An artist who approaches directing as an always-improving craft, Moraes has explored memory and collective identity (Caixa d’água: Qui-lombo é esse?), drawn delicate portraits (Monga) and created immersive experiences (Pattaki).

With her latest film Aurora (Dawn), Moraes introduces us to three women. These women could easily be interpreted as one single body, fragmented into three different moments of a woman’s life. First, La Niña, who’s just beginning a long process of becoming a woman; then, La Cantante, whose face bears the remembrances of brighter days; and last, La Señora, an elder who’s coping with the realization of her imminent encounter with death.

Aurora hints at so many aspects of a person’s existence that one must resist the temptation to merely look at it as a commentary on existential issues. To do so would be to make the mistake of relegating Moraes’ mise-en-scène to second level interest. Her directing choices create a permanent contrast between what is revealed and what remains unseen, turning the off-screen into a an almost physical, material presence. Each shot is a painting, where shadow and light draw lines between what has passed, what is still here, and what is yet to come. Even set design becomes metonymic representations and metaphors of prison and imprisonment, growing and aging, movement and lack thereof.

Without a doubt, Moraes’ Aurora is one of the most beautiful films in Brazil’s contemporary cinema.

GHOSTS

André Novais Oliveira’s second film came to the picture when the means of production – mainly digital cameras and sound recording devices – were changing the landscape of who could make a film in Brazil. Film festivals with a strong identity, such as Mostra de Tiradentes, also played a key role in legitimizing filmmakers and collectives whose origins, aesthetics, and ways of production wouldn’t haven’t been taken seriously in the years prior.

Fantasmas (Ghosts, 2010) is a trademark Oliveira film: its formal simplicity disguises his elaborate construction, while a plot develops towards which the audience feels deep empathy. A story about a broken-heart, obsession and friendship. Or is it a commentary on mise-en-scène and the power of the off-screen? Through a casual encounter between two long-time friends, the audience is invited to reflect upon the status of image in the contemporary world, all the while laughing as the story unfolds.

SOUL IN THE EYE

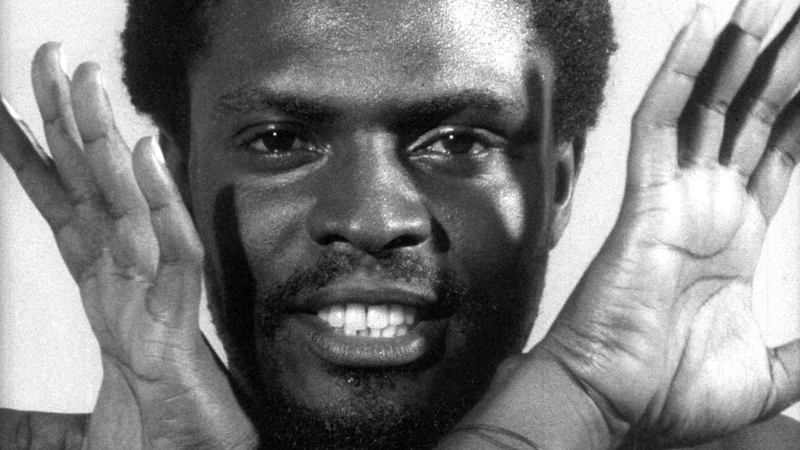

There are many angles through which one may approach Zózimo Bulbul’s first film as a director. A landmark in Black film in Brazil – or as we say in Portuguese, “Cinema Negro” –, Alma no Olho (Soul In the Eye, 1973) remains a powerful aesthetic experience to both new and frequent viewers of the film even five decades after its release.

Using the body as a canvas for Diasporic memories from the Black Atlantic (to quote Paul Gilroy’s book)1 as well as experimenting with film form, Alma no Olho tells a five-part story covering around 400 years in the history of the African Diaspora in Brazil. I would name those parts: Black body; An Idyllic World; The Boats are Coming; How We Have Survived; and, finally, Freedom (or The Becoming-Black of the World, to quote Achille Mbembe).

Alma no Olho’s aesthetic achievements metaphorically replicate our lives in the Diaspora. With highly unfavorable conditions and the never-ending dehumanization, Black people found and continue to find ways to thrive. Facing economic and racial adversity, Bulbul manages to create a universe full of symbols and meanings out very little: a studio, some props, John Coltrane’s music, his creative editing techniques and his own mind / body.

As a result, Bulbul creates an 11-minute film which is so innovative that, just like Mário Peixoto’s Limite, I feel compelled to watch it at least once a year to remind myself of what cinema can be.

NOIR BLUE

Ana Pi’s Noir Blue – Deslocamentos de Uma Dança (Noir Blue – Displacements of a Dance, 2018) illustrates the potentialities that reside in the dialogue between cinema and performance, urban interventions and plastic arts. A choreographer and visual artist, Pi’s first visual experiment (with what would later become her first film as a director took place during the 19th Artdanthé Festival in Vanves, France, when Pi first executed Noir Blue as a dance/performance show.

The cinematic extension of this work doesn’t just a register a performance, but it’s rather a visual fabulation around the ideas of belonging, displacement, embodied memories, and identity. Pi travels through different countries of the African continent, performing short dance pieces in various locations. All the while, her film unequivocally materializes the idea of the Black body as a canvas of memories from the past while also revealing the ways in which Black bodies project towards the future. Pi’s deliberate and slow-paced narration embellishes her camera work. She shares her perspectives from her journey with a rare patience, care and devotion to language, as voice over and image complement one another.

And then, there is the matter of colors. “Black is the color…”, sings Nina Simone in “Black is the Color of My True Love’s Hair”. “In the moonlight, black boys look blue”, recounts Juan in Moonlight. “Everything black, want all things black/ I don't need black, want everything black”, declaims Kendrick Lamar in “The Blacker the Berry”. Although Noir Blue doesn’t specifically refer to any of these works, I can’t help but think of these lines and relate them to a film that simultaneously confirms and disrupts conceptions around two colors, black and blue, as representative of Black.

NATURAL DAUGHTER

Aline Motta’s work was recently featured in MASP’s exhibition Histórias Afro-Atlânticas, arguably the most important curatorial project held at a major museum to map the work of Black visual artists in Brazil. She is an artist that has been constantly shifting between photography, film, and video installations. Filha Natural (Natural Daughter, 2019), her latest work, is a culmination of Motta’s years of researching her own family, through which she expresses a different perspective on the racial constitutions of our own families.

When working with film, Motta employs a variety of devices, notably plotting non-idealized connections between Black Brazilians and our ancestors from Africa. Motta’s works share common features, and both familiarity and strangeness are two key concepts to be found throughout them all.

Firstly, she uses narration as a tool to create discomfort rather than using it as a guiding path. Secondly, Motta positions photographs in sites where they initially seem alien, but we later learn her reasons for such arrangements. Lastly, sound and music not only create a sonic atmosphere, but also cause the lives of our ancestors to materialize in our current space-time.

Filha Natural turns the fragmentation imposed on us by slavery into a powerful aesthetic tool. “Francisca, a daughter. Whose daughter?”, asks Motta, the narrator. As she tries to fill in the multiple gaps in telling her/our story, we realize that fragmentation for Black people can only be combated with speculation and imagination. In Filha Natural, Motta is in search for an historical character, Francisca, in places where her presence has been removed. Since the effects of slavery impedes Black people from fully covering the gaps in our collective history, Motta investigates ways through which she can give Francisca some level of existence. Whether or not the character we see is actually Francisca, as we watch the film we feel as if some level of justice is given to her memory – and to the memory of many others.

KBELA

We Black Brazilians joke (with a tone of seriousness) that Brazil only discovered our existence in 2015. But jokes apart, there’s some truth to that perception. Despite the fact that we have been making movies in Brazil for at least 66 years (our stories and artists central to the very existence of Cinema Novo), we are only now beginning to witness a flourishing in the number of Black filmmakers in Brazil, primarily in a surge of Black cinema that has marked the last five years of cinematic production in the country. The film festivals, who for so many years actively relegated our productions to the status of second-class films, are now finally beginning to acknowledge our works.

Kbela (2015), directed by Yasmin Thayná, occupies an interesting place in this history. Initially, the film was absent from traditional Brazilian film festivals. However, Kbela was creating strong reverberations among Black film circuits at the same time that these festivals were ignoring Thayná’s work. This scenario was instrumental for Black players in the industry – myself included – to call out institutional racism in the Brazilian film industry.

Admittedly inspired by Zózimo Bulbul’s Alma no Olho, the aesthetic accomplishments of Kbela can’t only be attributed to its director. Kbela is the fortunate result of the creative energy of dozens of Black women who were either part of the film or whose work (as, for example, Priscila Rezende’s performance Bombril) inspired Thayná’s storytelling.

“Watching Kbela, I realized it was the first time I heard the sound of an Afro being picked in a film”, said a one viewer. Such a testimony illustrates how deeply hurt we are as Black spectators and the power residing in healing images, numerous of which can be found in Kbela.

I HAVE THE WORD

For Brazilians who identify as part of the African Diaspora, being denied the opportunity to trace our origins beyond the lineage of our grandparents due to the way that slavery structured our society can be immensely harrowing. Because of that, a film like Eu Tenho a Palavra (I Have the Word, 2008) can serve as a respite from the pains associated with slavery.

Lilia Solá Santiago’s work rebuilds the bridges that were burned by racism through the reminiscences of African languages in a small city in Minas Gerais. As a filmmaker engaged in a modern ethnographic approach to cinema, Santiago manages to create points of communication between two remarkable characters. In doing so, she delivers a work which heals many of the wounds we still bear.

Besides her current work as a teacher, researcher and curator, Santiago occupies a key place in the history of Black filmmaking: she was one of the few women active in the field when it was, even more than it is today, a male-dominated environment. Therefore, any account of the history of Black Brazilian cinema must acknowledge her important role.

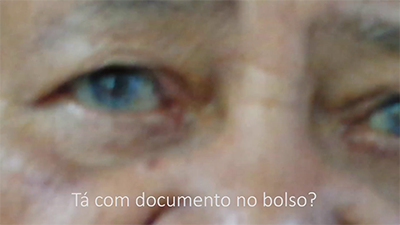

UNCONCIOUSNESS

As Marvin Gaye sings “What’s going on?”, we watch images of objects, houses, a cigarette, showers and streets shot from a first-person POV. We’re left with the same inquiry of Gaye’s music: what’s going on? What is this film that I am watching? Suddenly, a banal question is asked in the gravest of ways: “Are you taking your ID with you?”, to which our character replies “Most def. I ain’t giving them no chance”. Such dialogue tells me only one thing: I may not yet understand what film I’m watching, but I certainly can’t hit pause.

It pays off to remain engaged with Jéferson’s (In)Consciência [(Un)Consciousness, 2018]. Throughout the film we’re exposed to unexpected interruptions: city sounds, a contrast between the cacophony of noise and complete silence, an apparently random selection of songs, and an almost unbearable reliance on first-persion POV shots. Slowly, we begin to understand the film’s motive - it’s a profoundly sad reflection on police harassment and racial profiling.

Jéferson is a prolific photographer and cinematographer whose recent work, Jorge, has been selected by important short film festivals. He constructed (In)Consciência as a less palatable experience than Jorge. It would be wrong to dismiss the low production values of (In)Consciência as an impediment to a greater fruition. Jéferson plays with precariousness, pace, storytelling and character development in an intelligent way, revealing a refined awareness of narrative.

As we’re left speechless after the film reveals a major twist, we understand how sadly ironic its title is. A ‘gone-wrong’ film, (In)Consciência was meant to simply document the director’s departure and return to his neighborhood on the day before Brazil’s Black Awareness Day, November 20th. Instead, Jéferson ended up documenting how Black lives don’t matter in the eyes of the police.

CINEMA NOIR

Danddara’s ambitious second short, Cinema de Preto (Cinema Noir, 2004), has multiple intentions, the most evident of which is to portray the remarkable contribution of Abdias do Nascimento to the world of art, politics and academia. The less evident, but perhaps most fascinating intention of the film is to reveal what happens behind the camera on her film set.. In Marcell Carrasco’s essay within the current program of Limite, he investigates why it was so important for Zózimo Bulbul to highlight his crew’s ethnicity in Abolição (Abolition, 1988). Those who read Carrasco’s piece and watch Abolição will quickly apprehend Danddara’s mise-en-scène, which integrates her crew into the film itself. Cinema de Preto is a film in which she takes ownership over image-making. From the director to the lowest ranking person working on her set, Danddara presents the idea that Black cinema is not divorced from the labor put into making the film.

WINGLESS

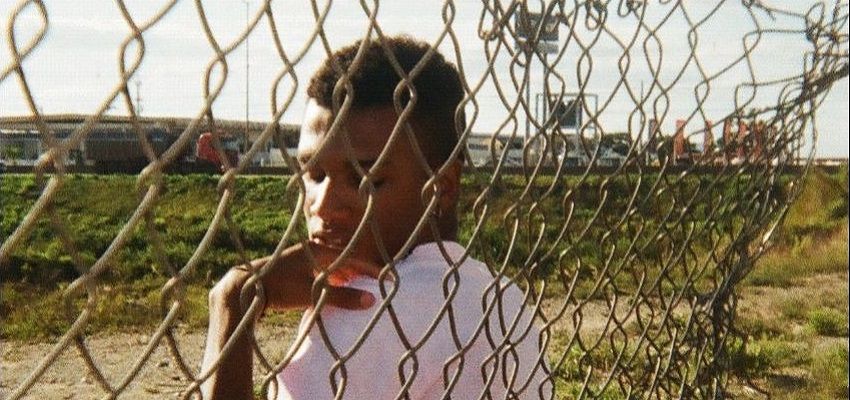

Almost a decade separates Renata Martin’s first short and her second. Between the filming and releasing of Aquém das nuvens (Below the clouds, 2010) and Sem Asas (Wingless, 2019), Martins became one of the most recognized faces among Black directors and writers. Her web series Empoderadas (Empowered Women, 2015-2016) is a landmark work in the representation of Black women on-screen and in advocating for their political and artistic recognition off-screen.

Sem Asas represents a continuation of Martins’ predilection for narrative cinema. The film features a Black family of two dedicated parents and one 12-year-old boy whose life is filled with love, care and tenderness. Sem Asas takes a dramatic turn away from that familial bliss as Martins tackles the ways in which police brutality remains a key concern for every Black parent. The film also explores the ways in which terror, fear and rage are all part of the growth process of Black children. In this sense, the story of Sem Asas’ connects diasporic experiences through the pain caused by racism. As I’m thinking of the film’s plot, a segment from Terence Nance’s Random Acts of Flyness’ comes to mind. “What are your thoughts on raising free Black children?”.

However, despite these dark themes and in a very Martins’ fashion, Sem Asas opens the door to hope and allows the audience to experience a “happy” ending.

BLACKN3SS

Diego Paulino’s Negrum3 (Blackn3ss, 2018) represents a defining moment for the construction of an anti-canonical history of Brazilian cinema. Centered around three young Black queer characters whose very existence constitute a political statement in São Paulo, Paulino’s film mobilizes references such as Afrofuturism, pop culture, Black techno and queer performance. The film has been met with lots of enthusiasm since its premiere at MO(N)STRA de Cinema LGBTT e Negritude in 2018, especially by Black audiences. Negrum3 energetically speculates Black futures and forges temporalities that are beyond those set by Western standards.

As perfectly put by critic Bruno Galindo, “Paulino’s film represents an astounding pulsion of life, it electrifies the body through the eyes (…), multiplying itself as an explosion full of desire for life”. For those who have watched Sun Ra’s Space is the Place (1974), you can compare Negrum3 to the opening line – “It’s after the end of the world. Don’t you know that yet?” Or, one can think of Marlon Rigs’s Tongues Untied, and the ways in which it uses performance within the documentary genre. By watching Negrum3, you’re becoming connected to a long history of Black artists experimenting with radical forms.

THEIR HAPINESS

Stories from the LGBTQIA+ community have been glaringly underrepresented in short films from Brazil. Even when looking at movies by Black directors, narratives that explore queer characters are still a relatively recent phenomenon.

Carol Rodrigues’ A Felicidade Delas (Their Happiness, 2019) is one of the recent films invested in sharing stories from that community. Two women meet at a feminist demonstration and the younger helps the older break free from the custody of a police officer. Initially strangers to one another, they create an instant bond which evolves from ideological solidarity to mutual attraction.

Rodrigues is an experienced screenwriter whose previous short films have dealt with abortion and isolation (A Boneca e o Silêncio), as well as with neglectful male parenting (Mãe Não Chora). With A Felicidade Delas, she delivers a touching and ephemeral love story that visually explores the contrasts and harmonies between the color purple and shades of dark skin. Rodrigues subverts our audience expectations in that the film initially presents itself as a work of realism, but then breaks with that style. It forges this break in a daring fashion, and that shows that as a creator, Rodrigues is not afraid to have her aesthetic tastes perceived as corny. Such personal confidence is exactly what allows Rodrigues to provide A Feclidade Delas with an exceptional ending.

* For a deeper investigation into works by Black filmmakers that focus on queer stories, please refer to my upcoming article for Blackstar’s Seen, titled “Traviarcado! Queer Intersections in Contemporary Brazilian Cinema”.

LOOPING

Maick Hannder’s Looping (2019) is the perfect transliteration of Frank Ocean’s first megahit, “Thinking Bout You”. Though the filmmaker from Minas Gerais has never claimed any personal connection to Ocean’s song, both works share a narrative about tender memories from early adulthood, as well as a first-person retelling of those intimate moments between two young men. “I remember, how could I forget? How you feel? You know you were my first time, a new feel”, sings Ocean. Looping’s mood very much echoes Ocean’s music.

Hannder’s film could also be associated with a tradition of fiction films that play freely with still photography. As he invites his audience to peak at a fragment of the main character’s imaginary diary, we understand his intentions in challenging the very idea of gazing. As the film ends, we’re left to question: Did his muse ever exist? Whose photos was he looking at? Are muse and creator two different entities?

There’s no need for the film to leave us with definitive answers. It isn’t about discovering the “real truth” behind the film’s form but rather experiencing it in its fullness, which speaks to a variety of feelings. We just have to embrace them.

CORES E BOTAS

At a time when Black artists were still acutely underrepresented in the short film format, Juliana Vicente’s Cores e Botas (Colors and Boots, 2010) became a reference point with its straight-to-the-point plot. Imagine a chaotic TV game show for kids hosted by a blond woman in her late 20’s dressed as if she were a mash-up of a Hentai character and “Oops!... I did it again”’s Britney Spears (I kid you not). Now imagine if that woman, Xuxa, was seen daily by almost every kid for 20 years on Brazil’s top media conglomerate, Rede Globo!

In her shows, Xuxa had stage assistants, the Paquitas, who dressed like American high school cheerleaders. And, like every other girl from the late 80’s and early 90’s, that’s what Cores e Botas’ protagonist, Joana, wants to become: a Paquita. There’s only one tiny issue: in a country where 54% of population self-identify as Black or brown, no one had ever seen a Black Paquita. Joana’s parents want to support her belief that she can become the first.

A decade after hitting the film festival circuit, and almost 40 years since Xuxa (now reported to be the 11th richest female artist in the world) was first introduced as “The Queen of the Little Ones”, Cores e Botas remains an integral work within the history of 21st century Black Brazilian cinema.

CAROLINA

The writer Carolina Maria de Jesus, whose trajectory has been returned to the center of Brazilian literature as a result of Black activism, has been the subject of several films. Arguably the most relevant effort yet to cover her life is Jeferson De’s short film Carolina (2003). Besides highlighting Carolina’s literature, the film also serves as a vehicle for another Black woman whose artistry has been systemically underappreciated: the actress Zezé Motta, who plays Carolina in the film.

It is an event in itself to watch the forged connection between Carolina, author of Child of the Dark: The Diary of Carolina Maria de Jesus,2 and Zezé, best known as the protagonist of Xica da Silva (which is a film that subscribes to racist conceptions around Black women’s bodies). But Carolina, the film, is also a tender peek at the intimacy of an artist. As the director breaks the fourth wall and makes the camera present through movement, we feel closer to Carolina the author.

The final point of interest around this film is the director. Jeferson De has become a veteran filmmaker since his 1999 debut Gênesis 22, and he is one of the few Black directors who has had a steady career in Brazil. He’s also known as a key figure of Dogma Feijoada, which in the early 2000’s challenged the lack of racial diversity in the Brazilian film industry. Its biggest accomplishment was the manifesto “Dogma Feijoada – Gênese do Cinema Brasileiro” (“Dogma Feijoada – Genesis of a Black Brazilian Cinema”).3

PERSONAL VIVATOR

With a background in documentary studies from Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film München, Sabrina Fidalgo has been a constant voice among Black Brazilian filmmakers throughout the last decade. Her films deal with a variety of topics ranging from immigration and empathy (Black Berlim) to samba culture and toxic competition (Rainha).

Personal Vivator (2014), her sixth short as a director, uses sci-fi to de-normalize the racial and economic oppression that structure our society. Disguised as a documentarist, an alien called Rutger is sent to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s sixth most segregated city*, to investigate how humans behave. As he’s introduced to our reality, he quickly realizes that the “personal vivators”, which are those rendered invisible by society, are the most interesting characters.

Fidalgo plays with notions such as realism and objectivity by creating a multi-layered portrait of a complex social structure in which economic oppression and fantasies around class superiority come down on the film’s characters in a ripple effect.

* According to a ranking created by Nexo newspaper based on data collected by IGBE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). The full report is available at: https://www.nexojornal.com.br/especial/2015/12/16/O-que-o-mapa-racial-do-Brasil-revela-sobre-a-segrega%C3%A7%C3%A3o-no-pa%C3%ADs.

MARTINHO DA VILA, PARIS 1977

Behind the facade of this straight-forward documentation of a trip to France by Martinho da Vila (who is one of Brazil's most acclaimed singers and composers), there lies a film that reflects profoundly on key issues such as North-South dynamics, immigration, and belonging. But as a film with and about a character whose existence is the epitome of swag, those issues are approached in an everyday-like manner.

Comparing Paris to his hometown Rio de Janeiro, he says: “The Paris’ subway is just like any other train that takes you through the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. It just comes faster, that’s all”. What could have been romanticized by a person who idolizes Europe, Da Vila sees the matter-of-fact reality, not the fictional idolization built up around it.

Ari Candido Fernandes, director of Martinho da Vila, Paris 1977, is now a veteran filmmaker who has directed five other short films. But at the time in which this film was made, it was Fernandes’ sensibility as a young journalist that was determinant in capturing Da Vila’s philosophical approach and sophisticated understanding of his own art. As a film, it today operates as a flash back of a moment when Da Vila had just reached his artistic peak.

JERUSA’S DAY

Jerusa is an older woman celebrating her 77th birthday when she receives an unexpected visit from Silvia, who works for a survey institute. Before meeting one another, they both have very different agendas for their day. While Jerusa is making her house nifty for her soon-to-come children, Silvia is desperate to knock on as many doors as possible in order to complete her survey job. What started as a chance encounter is soon transmuted into an ephemeral relationship.

Dia de Jerusa (Jerusa’s Day, 2014) is Viviane Ferreira’s best-known film as a director and it is a tender work that engages the audience through an empathetic story line, captured by a camera deeply invested in set design and details. The film also occupies a relevant place in the history of Black-directed short films because of the actress who plays the film’s main character. Jerusa is played by Lea Garcia, the 87 year old iconic Brazilian actress who has been active since the 1950s and has played a myriad of roles, including Jorge’s assertive sister in Compasso de Espera (1969).

Dia de Jerusa has a touching storyline, it utilizes music in a well-structured way, and it features beautiful camera movements and narrative pacing. However, perhaps the most important element ofDia de Jerusa is that it represents a fruitful partnership between Viviane Ferreira, a valuable voice from the younger generations who has benefited from those important artists that preceded her work, and Lea Garcia, a refined artist that has been breaking grounds in Brazilian television and film for decades.

CROSSING

IFFR’s opening short film in 2019, Travessia (Crossing, 2017) may arguably be the simplest, and yet one of the most sophisticated works to come from Brazil in recent years. With a background in cinematography, Safira Moreira makes use of three powerful cinematographic tools in her 5-minute film.

First, Moreira invites us to challenge how the very act of gazing carries, reproduces, and reinforces power relations. For Black bodies like ours, being photographed so frequently meant a hierarchization that relegated us to inferiority – an issue also investigated by Christopher Harris’s 2014 installations’ A Willing Suspension of Disbelief and Photography and Fetish. Second, Moreira diagnosis how Black families in Brazil haven’t had the financial means to register ourselves on camera. And third, as if Moreira were following bell hooks’ teachings in “The Oppositional Gaze”, Moreira gazes at the empty canvas and dreams of the photographs yet to be taken.

Through this multidimensional gesture, Travessia provides healing to shattered subjectivities, as well as envisaging a future in which Black bodies can’t be erased from the picture.

HOW MANY WERE MEANT TO BE?

As a younger generation of Black filmmakers have been steadily entering the film scene for the last three years, we’ve witnessed a surge of films that attempt to portray their own collective bodies. Vinícius Silva’s third short, Quantos eram pra tá? (How Many Were Meant to Be?, 2017) might be the one film that is less shy about paying homage to its peers.

A continuation of Silva’s preference for hybrid films located somewhere between fiction and documentary, his meticulous editing becomes a central part of the film’s in-your-face discourse. As we follow the lives and tribulations of three Black men and women in their mid-20’s, we come to understand the film’s politics: enough of the cosmetic change, it’s about time for Reparation. In a country where camaraderie is still a common trace in intellectual debate, Quantos eram pra tá? is adamant on who it targets. The closing song of the film, Rihanna’s “Bitch Better Have My Money”, couldn’t have been a more apt narrative solution.

PARA TODAS AS MOÇAS

Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro’s trajectory as a visual artist is very unique when compared with the typical trajectory of artists within the broader landscape of Brazilian cinema. She has been freely experimenting with a variety of forms - from podcasts to poems, from cartographies addressing a city’s hostility towards queer Black bodies to powerful videos such as Para Todas as Moças (To All the Ladies, 2019).

These works all share her profound commitment to investigating new ways of existing in a world that embodies trauma to non-comformative bodies. Para Todas as Moças, in particular, speculates about the new foundations of other worlds, which clearly won’t be cisgender-centric nor subscribe to Western’s divorcement of mind and body, earth and firmament, hell and heaven. Playing with images, symbols and sounds, she invites us to interact with queer Afro-Diasporic cosmologies.

The result is a very short film that might initially seem easy to understand, yet it contains many hidden secrets. This is a very important notion to candomblé, Brazil’s most important religious practice of African descent. Envisioning a never before seen level of freedom, Para Todas as Moças refills my body with all the promises of emancipation and a strong belief that racialized queerness is the future to which we should aspire.

1. Published in 1993 by historian and scholar Paul Gilroy, the book “The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness” takes as its main point of interest to investigate the cultural exchange between Black people from the Diaspora that took place during the Transatlantic Slave Trade. In his analysis, the Atlantic Ocean became a metonymy for mutual influence between members of the Diaspora.

2. A writer who applied all her energies in getting published regardless of the walls erected by racism and sexism, Carolina Maria de Jesus had three other books published during her lifetime: Casa de Alvenaria – Diário de Uma Ex-Favelada (1961), Pedaços da Fome (1963) and Provérbios (1963). A thorough investigation of her life and work will be presented at the upcoming exhibition “Carolina Maria de Jesus, Um Brasil para os Brasileiros”. Curated by Hélio Menezes and Raquel Barreto and to be held at Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS), the exhibition aims to correct misconceptions around her oeuvre. One of them is that her writing was merely an index of reality, rather than the elaborate work of an artist.

3. The English version of the manifesto has been published in the 20th Belo Horizonte Int’l Film Festival’s catalogue. The festival hosted the retrospective “Black Brazilian Cinema: Episodes of a Fragmented History”, which I curated. The manifesto was of the main pieces I chose to tell a history of Black directors in the short film format. The text can be accessed online at the link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1tYxGjUA-mCO4lfO6GRKcp9g1Mo3Jx0s0/view (page 170-173)