This selection of “Ten Brazilian Films that Remain in the Shadows due to Poor Accessibility” is based on my experiences as a film preservationist over the last fifteen years as well as my work as a professor and film club organizer. As a film professor and film club organizer, I often faced the difficulty of finding a copy of a film that I wanted to screen in class or at the club. However, these difficulties in accessing Brazilian films has changed over time. For example, In the mid-2000s, I and some friends ran a film club dedicated to Brazilian films at the Museum of Modern Art FilmArchive in Rio de Janeiro (Cinemateca do MAM) called“Cineclube Tela Brasilis”. There, we had the chance of using the vast collection of film prints of the MAM Film Archive and we usually chose films that people couldn’t find anywhere else. So, we often programmed 35mm or 16mm prints of Brazilian films that weren’t available in other carriers, either video or digital. Some of the films we screened then are still widely rare and unknown as they haven’t been digitized since that time. In this list compiled for Limite, Veneno is one of the titles we screened in Tela Brasilis program of July 25th, 2009. On the other hand, the short film Bossa Nova: a moderna música popular brasileira, also in this list, is a title that we wanted to show in one of Tela Brasilis exhibitions, but we couldn’t, as there was only a preservation master, but no exhibition print, neither on film nor digital.

As a film professor at Federal Fluminense University (UFF), whereI have been teaching courses on Brazilian Film History to graduate students for almost ten years, the problem is quite different. In the classroom, I am only able to screen DVDs or digital files, which often limits the selection of Brazilian features from the silent period to the 1940s that I can show. Unfortunately, many titles that are important to show to students exist only in very bad digital copies taken from VHS tapes, which is the case of Alô, Alô, Carnaval, for instance. That’s why I’ve occasionally taken the opportunity to bring my students to the MAM Film Archive for their classes, where we would screen films in beautiful 35mm prints, something that my students are not used anymore. That was when I was able to watch, for example, a 35mm print of É Simonal (mentioned in the list) that was borrowed from the Cinemateca Brasileira’s collection.

Fragments of Terra Encantada (Silvino Santos, 1922)

The feature-length documentary by Portuguese-Amazonian filmmaker Silvino Santos, shot at the time of Rio de Janeiro’s Universal Exhibition,1 survives only partially, but what remains of it reveals extraordinary images of what was then Brazil’s federal capital.

Once these fragments were rediscovered, they were first seen again in 1970 documentary short films by Roberto Kahane. These documentary shorts were, for many years, the only way to glimpse the scenes filmed by Silvino. Apparently, there are also outtakes of Terra Encantada preserved at the Brazilian National Film Archive. In addition to being dispersed in different films and archives, these fragments filmed by one of the most talented Brazilian filmmakers of the silent period are also not digitized and accessible.

São Paulo, sinfonia da metrópole (dir. Rudolf Rex Lustig and Adalberto Kemeny, 1929)

This fantastic feature is, alongside Mario Peixote’s Limite (1931) and Humberto Mauro’s Ganga Bruta (1933), one of the most inventive Brazilian silent films. The documentary is not only related to Walter Ruttmann's Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927), but also to Vertov's masterpiece, Man with a Movie Camera (1929). No good quality digital copy of the film exists, and it currently circulates through a digitized VHS tape that does no justice to the incredible photography within the original work.

Alô, Alô, Carnaval (Wallace Downey and Adhemar Gonzaga, 1936)

This Brazilian musical comedy starring Carmen Miranda, among other great performers of the time, is the oldest preserved feature from the genre. The film was restored by its production company, Cinédia, and had the new 35mm print premiered in 2004. However, until today there is no circulating high quality digital copy of Alô, alô, Carnaval. The film is widely seen, including in film schools, in a miserable digitized version of an old VHS tape.

Eterna esperança (Leo Marten, 1940)

The only production of the Companhia Americana de Filmes from São Paulo - a kind of predecessor to Vera Cruz - Eterna esperança survived in an incomplete version, currently available only on 35mm. The film was a huge financial failure and is still rarely seen. Without an accessible digital copy, Eterna esperança has only been seen by researchers who have had the opportunity to attend the few screenings that took place in film archives over the last few years. This is a real pity given that today there are only a few preserved Brazilian feature films from the 1940s.

Carnaval no fogo (Watson Macedo, 1949)

Considered by many scholars as the film that marks the beginning of the successful formula of Atlântida's chanchadas,2 Carnaval no fogo has been waiting for years to be restored. The only circulating digital copy of this chanchada is sourced from a DVD that was sold by mail in the early 2000s by the collector Paulo Tardin, who had a rare but incomplete 16mm copy of the film. According to informal reports, the negatives of the classic scene in which comedians Oscarito and Grande Otelo parody Romeo and Juliet were removed in order to be used for the 1974 compilation documentary Assim era a Atlântida, directed by Carlos Manga.

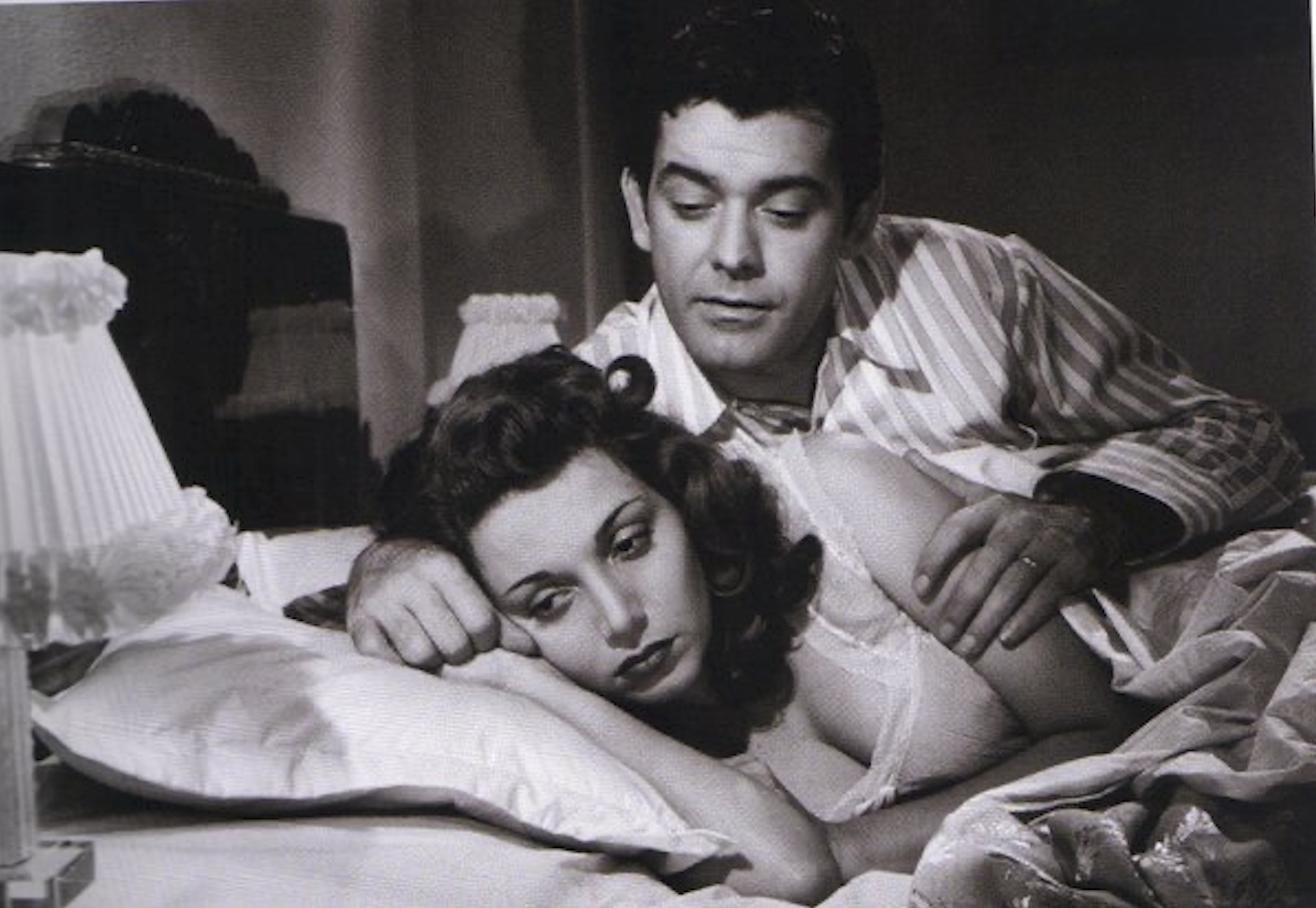

Veneno (Gianni Pons, 1952)

Veneno is one of the best Brazilian film noirs and it is one of the last works of gifted director of photography Edgar Brasil, who shot Limite (1931). It is also one of Vera Cruz's lesser-known productions, a title that is absent even from the Banco de Conteúdos Culturais website, where almost all the other films of the studio are available. Featuring famous star Anselmo Duarte in the role of a villain, this interesting film remains unknown largely due to the absence of any kind of digital copy.

Cinco vezes favela (several directors, 1962)

This film in five episodes presents a very curious case of preservation and digitization. It was produced by the active and politicized Center for Popular Culture of the National Students Union (CPC da UNE), which is one of the precursors to Cinema Novo. The short films by Leon Hirszman (Pedreira de São Diogo) and Joaquim Pedro de Andrade (Couro de Gato) were included in projects to restore the works directed by these filmmakers and circulate today in excellent digital copies that were released on DVDs (andeven Blu-ray in the US). However, the other three episodes, directed by Marcos Faria, Miguel Borges, and Carlos Diegues, only circulate in copies taken from VHS tape. Several other films by filmmaker Miguel Borges, in particular, are in a similar or worse preservation situation.

Bossa Nova: a moderna música popular brasileira (Carlos Hugo Christensen, 1963)

Bossa Nova is a short documentary, shot in color, that was produced at the height of the international success of the Brazilian bossa nova music genre that had hit songs such as “The Girl From Ipanema”. Even so, the film is in need of urgent restoration treatment. Bossa Nova survives only in deteriorated film materials, and there are currently no exhibition copies of the film either in film or digital formats. Bossa Nova is just another example from the vast universe of Brazilian short films that are currently unknown and which are in danger of being lost before new generations can come into contact with them. It is also an important work by Carlos Hugo Christensen, an Argentine filmmaker who dedicated himself to filming the most famous icons of Brazil 1960s, from Copacabana to Pelé, even passing through bossa nova.3

É Simonal (Domingos de Oliveira, 1970)

É Simonal is a film that has been forgotten for years, just like its protagonist, the singer Wilson Simonal (1938-2000). Simonal was ostracized after being accused of collaborating with the the Brazilian Military Dictatorship which lasted between 1964 and 1985. In 2009, a documentary feature about the singer, titled Simonal: Ninguém Sabe o Duro que Dei helped to rescue the artist’ fame, but the film was forced to use excerpts from a very faded video copy of this production made at the height of Simonal's success. In 2010, the Brazilian National Film Archive struck a new 35mm print of this film, shown in the “Classical and Rare Brazilian Films” series, but it was practically never exhibited again after that. Thus, throughout the last few years only a few people have been able to see the beautiful colors of this Tropicalist musical that remains digitally inaccessible to the wider public.

1. Universal Exhibition or the World’s Fair were large events designed to showcase international achievements that were very important in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Terra Encantada was shot during the Independence Centenary International Exposition, held from 1922 to 1923 in Rio de Janeiro.

2. Chanchada was the term given to the Brazilian popular musical comedies of the 1940s and 1950s by critics of the time. These critics considered these films to be simply bad copies of Hollywood features of the same genre. Atlântida was the most famous, but not the only, studio to produce chanchadas.

3. I’m referring here to Christensen’s films Rei Pelé (1961), a biopic, and Cronica da Cidade Amada (1964), a widescreen film that can currently only be seen in a horribly cropped digital copy taken from a VHS tape.