Cinelimite: Your careers intersect between filmmaking and film scholarship. How did you meet and how did you start working together?

Estevão Garcia: Luís Alberto, aka ‘Morris Albert’ to his close friends”, and I first met when we were critics and writers for Contracampo, an online film magazine. Every Monday the writers would gather at a bar in the Botafogo neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro to drink beer, talk films and set up the next edition of the magazine. After the meeting, we’d go to another bar and the last two guys remaining were always Luís and myself. This is how we became friends and ended up working together.

Luís Rocha Melo: Contracampo magazine was truly an important gathering point. The first decade of the 21st century was really atypical for Brazil. We had a government that was concerned with social inclusion, defending public and free education, and policies in favor of cultural diversity. There were many film festivals, many grants and stimuli to finance and develop projects. The mood was very different than the current depression we’ve sunk into since 2016. I got a master’s degree in Communication, Image and Information in 2004, from the Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF), where Estevão was an undergraduate student. Estevão had made a very interesting film, O latido do cachorro altera o percurso das nuvens, co-directed with Rebecca Ramos, Camila Marquez and Raul Fernando. If I’m not mistaken, it was shot on super-8mm, and it was influenced by dadaist cinema, by René Clair’s Entr’Acte. It proposed a strong dialogue with silent cinema. I, on the other hand, had just co-directed with Alessandro Gamo the medium length documentary O Galante Rei da Boca, about the legendary producer Antonio Polo Galante, whose nickname was “king of the Boca”,1 and was one of the most prolific film producers of the popular cinema made in São Paulo, in the Boca do Lixo region between the 1960s and 1980s. I’d always wanted to combine research and filmmaking. The 2000s were, for a whole generation of cinephiles, critics and filmmakers, a time of discovery and contact with films and filmmakers we had only heard or read about, but whose work wasn’t available to us. The internet hadn’t yet become what it is today, film prints were still shown in cultural centers, cinematheques, and alternative movie theaters. The Mostra do Filme Livre was fundamental for this, as since 2002 they were held at the Banco do Brasil Cultural Center, as well as the Cinema Marginal retrospectives organized by Eugênio Puppo in São Paulo and Rio, and above all the retrospectives curated by researcher and curator Remier Lion, especially Cinema Brasileiro: a vergonha de uma nação,2 in 2004, and Malditos filmes brasileiros!,3 in 2005, which I consider two of the most important and triggering historiographic revisitings in the history of Brazilian cinema. Estevão and I would attend these screenings and events, write about them, talk in bars, and from that exchange of ideas came the possibility of us making a film together.

CL: When I try to explain Que cavação é essa? to friends, they find it almost hard to believe. The film approaches the themes of preservation, memory of Brazilian cinema and specifically silent Brazilian cinema with irony and humor. How did you come to this approach? What was the original conception and how did it develop into what we see in the film?

EG: Actually, our original idea was to make another film whose temporary title was Cidadão Quem??? (Citizen Who???).4 It would be a spoof of the Orson Welles film [Citizen Kane] starring comedian Jorge Loredo (who created the famous character Zé Bonitinho). The plot was that the millionaire Quem had a “film tree” in his farm, and every film to fall on this cinematographic orchard would be seen onscreen. Each film would be a spoof of an era of Brazilian cinema: cavação, chanchadas, etc. Various films inside a film. However, the cavação segment turned out so interesting that it became our main focus. So, we scrapped the Cidadão Quem??? project and decided to develop the script for a film that would make homage to cavação films of the 1910s and 1920s. But, during the writing process, we realized that restricting it to the silent era wouldn’t be enough and we could frame the cavação as a timeless, structural phenomenon of Brazilian filmmaking. Then came the idea to make two films inside the film: the cavação from the 1910s and the institutional newsreel or “complemento nacional”5 from the 1970s. The second one became a short documentary on film restoration and preservation, and it deals, among other things, with the restoration of the film from the 1910s that covered the barbecue at Colonel Alexandrão’s farm.

LRM: The Cidadão Quem??? project was conceived from an interview that Estevão, Remier Lion and I did with Jorge Loredo for Contracampo in 2004. Jorge Loredo lived in a hotel in the Flamengo neighborhood, and we interviewed him in the lobby. Cidadão Quem??? was never filmed, but it made its way into Que cavação é essa?. You can see it as one of the posters on the wall of a room at the Cinemateca do MAM, during the scene where Hernani talks about silent Brazilian cinema. But besides the Cidadão Quem project (it had another title: Memórias de um amnésico),6 I would say Que cavação é essa? spawned directly from the Brazilian cinema history course taught for a year (2005-2006) by professor, researcher and current director of the Cinemateca do MAM Hernani Heffner at the Cinema Odeon movie theater, in the Cinelândia district of Rio de Janeiro. I think that course, organized by Tela Brasilis, was an event that defined a generation. All who went there every Saturday morning from 9 AM to 12 PM to watch films from the archive of the Cinemateca do MAM in 35mm and to attend Hernani’s fantastic classes afterwards received an immense Brazilian film education. At least to me it was an unforgettable experience. And it wasn’t just film students who attended. The Odeon, with almost 600 seats, would be packed by film students, researchers, cinephiles, critics, and people with general interest in Brazilian cinema. From June to December 2005, the first module of the course was mostly dedicated to silent cinema, especially the so-called “filmes naturais”, i.e. films that could be identified as documentaries, newsreels, travelogues, family home movies, institutional films, etc. Those “naturais” (which earned the name because they were shot “in nature”) had been despised by traditional historical researchers of Brazilian cinema from the 1950s to the 1980s. Those were the so-called “filmes de cavação”.7 The “cavadores”8 were cameramen who sought financial sponsors among politicians, rural landowners, industrialists or rich families. That is, they “dug up” resources with which to film. They were very badly regarded. Film historians and film critics, in turn, were always interested in fictional films (or “filme de enredo”,9 in the terminology of the time), that is, feature films with actors, make-up, costumes, scripts, studios, etc. In Brazil, however, fictional films were, for many years, especially from the early days until the 1940s, the exception, not the rule. The rule was precisely the “natural” films, which kept producers, cameramen, laboratories, etc. at work.

As I said before, when we came up with the project for Que cavação é essa? Brazil was going through a unique moment, as it had a democratic and inclusive government that focused on public policies for preserving and stimulating cultural activities. Many silent films were restored and new research about Brazilian cinema was conducted inside and outside universities. All of these initiatives brought new perspectives in their historical and methodological analyses, and mostly took “natural” films to a privileged position in their study, breaking with tradition of classical historical research. Strictly speaking, this process of historical revision started in the 1970s, but it was only in the late 1990s that it gained tremendous momentum. One example is the book Viagem ao cinema silencioso do Brasil, organized by Samuel Paiva and Sheila Schvartzman, and edited in 2011. This book is the outcome of a research group that, beginning in 2002, met once a month at the Cinemateca Brasileira to watch, study and discuss silent Brazilian films. Que cavação é essa? debuted at the 2008 Brasília Festival. So, it was contemporary to this new wave of interest in old Brazilian cinema. However, in this case, rather than our interest materializing in articles or retrospectives, it did so in the form of a film - or in “two films inside a film”, as Estevão put it. Actually, that reference to the 1970s in our film, with the “complemento nacional” Restaurare, is reminiscent of the origins of this process of historical revision in Brazil. The “diegetic year” of Restaurare, as the censorship card10 at the start of the second part tells us, is 1974. This was the same year in which Paulo Emilio Salles Gomes wrote the famous piece “A expressão social dos filmes documentais no cinema mudo brasileiro (1989-1930)”, published in the annals of the I symposium of Brazilian Documentary Film, in Recife, Pernambuco. In this essay, he coined the notorious formula of the “filmes naturais” whose themes are “Splendid Cradle”11 and “Rituals of Power”.12 1974 is also a call back to the time when Cinema Novo and the military regime were closer than ever, as well as the start of state policies to help the cultural sector (which included film preservation), by Embrafilme. That’s where the “official” tone comes from in Restaurare, which makes two references, both to the notion of “cultural film” with links to the State (a cultural form of “cavação”) and newsreels made by the National Agency. Skipping ahead to the 2000s, we see Paulo Emilio’s formula of “Splendid Cradle” and “Rituals of Power” questioned by Hernani Heffner in his courses and in his 2006 piece “Vagas impressões de um objeto fantasmático”, which was released at the same time as the production of Que cavação é essa?. So, it’s not a coincidence that Hernani is one of the main characters in our film, where he plays the Film Archaeologist. I believe Que cavação é essa? is linked to all of those references; some more explicitly and some indirectly.

CL: If I'm not mistaken, Que cavação é essa? was shot on 35mm film, something unusual for a short film, even in 2008. How did you get financial support for such an ambitious project? Was filming on 35mm an easy decision to make from a financial and aesthetic point of view? What was access to this type of equipment in Brazil like in 2008?

EG: The film’s postproduction was in 2008 but it was shot between the end of 2005 and the start of 2006. In 2005, its script won the first prize in a FORCINE grant intended only for final projects at film schools. By then, I was finishing my bachelor’s degree in Cinema and Audiovisual studies at UFF, and I submitted Que cavação é essa? as my concluding project. With the prize money we were able to shoot it on 35mm.

LRM: We were shooting Que cavação é essa? during a period of transition for the audiovisual sector. A lot of things were still being shot on film. Digital hadn’t become the norm yet, but many theaters were being equipped for digital projection and most of the young filmmakers and film students were shooting on digital. Many projects were still being made using the transition of video to film and vice-versa. These moments of transition are always very interesting, as they open up multiple possibilities for experimentation. In that sense, the fact that we shot Que cavação é essa? on 35mm film represented a radical gesture of experimentation made possible by the institutional structure of a public federal university. In addition to the infrastructure provided by the university, we had the support of Kodak, LaboCine (previously named Líder laboratory), Apema video rental store, and CTAv (Audiovisual Technical Center). Apema and CTAv lent us a 35mm camera, electrical and technical equipment, and an optical printer to make table-top effects, the intertitles in the first section of the film, and end credits. It’s worth noting that Hernani Heffner was fundamental during postproduction, as he mediated our business with LaboCine, Rob Digital, where the sound was mixed, and Movedoll, where the title cards for the sponsors and supporters were made. The sound was also vital, and we worked with Luís Eduardo Carmo in sound editing and mixing. He’s an inventor and an artist.

But going back to what I was saying about experimentation: I consider that to be an important aspect when discussing Que cavação é essa?, especially because the challenge of shooting it in 35mm required deep technical and aesthetic research. So, we can’t forget to mention the cinematographer, William Condé, who was also an undergraduate film student at UFF. William played a crucial role in every part of the production. He was involved since the initial meetings when we agreed to drop the Cidadão Quem??? project and started discussing making only the “cavação” film, up until the laboratory color grading process for the final copy. William did all the research on the photographic resources used in the film, and in that sense his work was not only extremely creative, but also a work of historical research, in which he tried to emulate the effects of orthochromatic negatives with emulsions that are much more sensitive than those used in the 1910s and 1920s. To me, the experimentations with negative film conducted by William during that research period would warrant an exclusive interview with him. Through the ingenious combination of various kinds of emulsions, different expositions, filters and development processes, William was able to simulate the halo of bright lights, the loss of definition in black areas, and the contrast. So, everything that could be done very easily today using two or three plug-ins, William did with his own resources during shooting, by combining exposition, filters, and negative sensibility. He handcrafted an iris, which he used in the orgy scene. So, the preservation discourse in Que cavação é essa? isn’t just in the theme or in what is seen and heard, but also in the very texture of the images. That was only possible because we shot it on 35mm film and because we had the talents of William Condé. I think we wouldn’t be able to repeat that feat today. It's almost impossible. What mattered when we made the film was the handcraft mechanical process of filmmaking. I think that we unconsciously knew it was a unique opportunity to shoot a film under those conditions. Indeed, a few years later, the digital revolution happened. If we want to show Que cavação é essa? today, in the original format, we won’t be able to find a screening room with a 35mm projector, which is actually ironic. There are few exceptions - the CineArte UFF theater, for instance, or the Cinemateca do MAM; where, by the way, the two 35mm copies of the film are stored. On the other hand, it’s great that today we’re able to share our film on a platform like Cinelimite.

CL: Que cavação é essa? starts with the staging of a film from the silent film era called Um alegre churrasco na estância do Cel. Alexandrão (A Joyful Barbecue in Col. Alexandrão's resort), which, according to the information in the film, would have been restored thanks to the joint efforts of the Fluminense Federal University, the Audiovisual Secretariat of MinC, and Forcine. When watching the film, we realized that there was great care and attention to detail in the recreation of the settings, characters, circumstances and even the spelling of a real film of that time. Which films served as inspiration and reference for Um alegre churrasco na estância do Cel. Alexandrão?

EG: We watched some “cavação” films from the Cinemateca do MAM archive. One of them was actually a barbecue hosted by a colonel. The research of that kind of material was a great inspiration.

LRM: Yes, we had the opportunity to see many films. Among them, Aristides Junqueira’s Reminiscências, one of the oldest surviving Brazilian films, from 1909. It’s a family film, where Colonel Junqueira and family appear from the start. Another remarkable film was Cidade de Bebedouro (1911), a Campos Film production, which featured panoramic shots of the titular municipality. Those panoramas, as was common with “cavação” films, were always unsteady and shaky, which we sought to emulate by tightening the head of the tripod. Other references include As curas do professor Mozart (1924) and A catastrophe da Ilha do Caju (1925), both produced by Botelho Film. We really liked the fact that, in the second film, the intertitles mentioned a “catastrophe” but all that was shown was a broken window. We also tried to emulate that with the scene of the “tragic fire in Colonel Alexandrão’s land”, where all you can see is smoke, ashes, a burnt tree trunk and a pair of boots. On the other hand, the character played by Luiz Carlos Oliveira Júnior, the guest who woos the Colonel’s “prettiest daughter”, was influenced by the “squanderer” character in A Filha do Advogado (Jota Soares, 1927), a fictional film of the Recife Cycle.

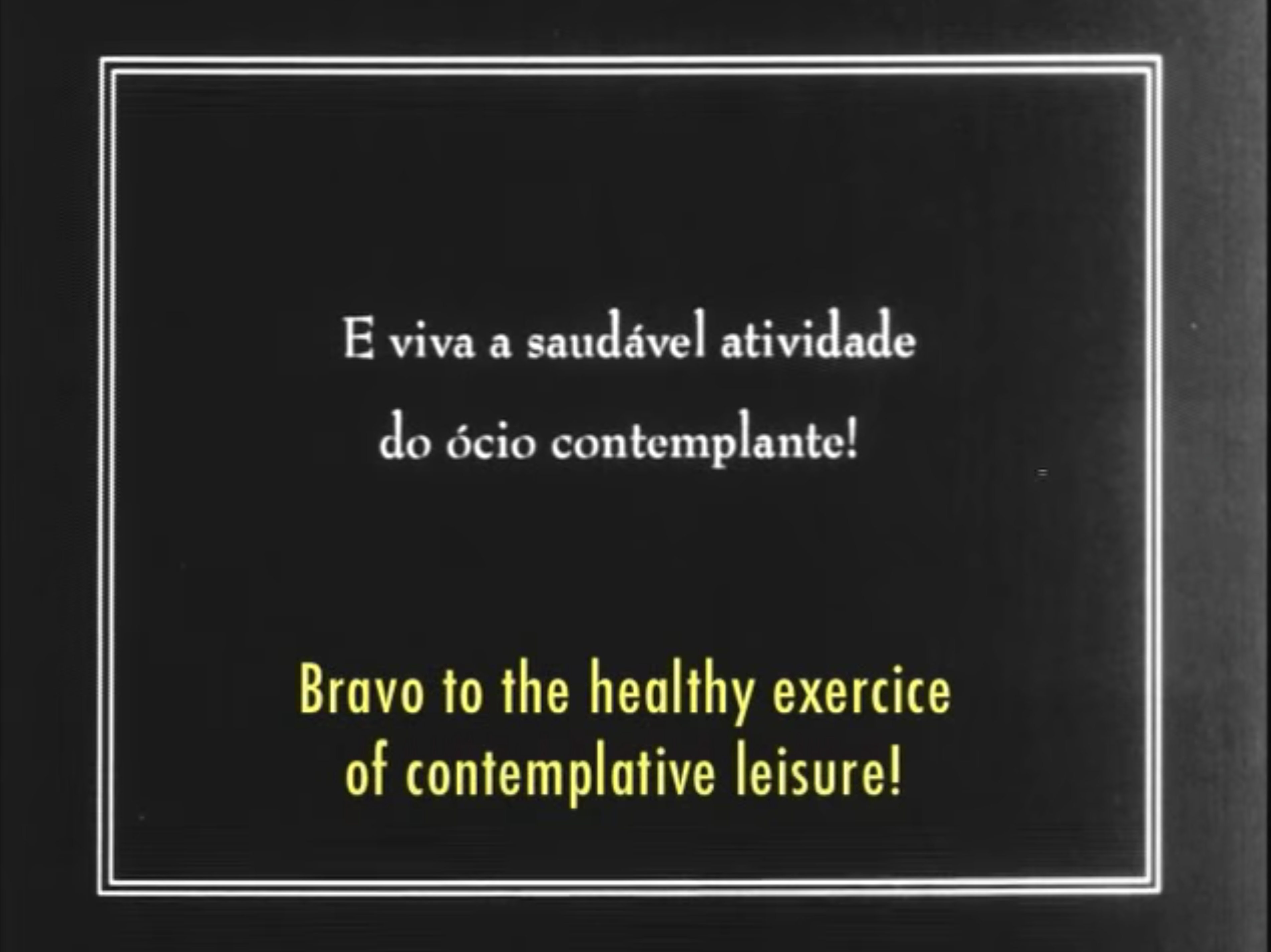

CL: The intertitle cards created for the first part of the film are often very humorous: "Bravo to the healthy activity of contemplative leisure"! What was the process like of drafting the text for these title cards?

LRM: Brazilian silent documentary intertitles have yet to be properly researched. Very often they contain involuntary humor, especially when they try to convey a serious or majestic tone to trivial events and mediocre authorities - as was the case with many colonels, politicians, industrialists and rural landowners portrayed in those films. The intertitles in As curas do professor Mozart (1924) are a good example. That film is a festival of complicated, sensationalist sentences. When the images appear, they immediately contradict and expose the fraud in those sentences. That constant contradiction between literary and visual reveals a society eager to present itself as “modern” when it was in fact deeply backward, reactionary, conservative, preserving the mentality of a slave society. The subliterary quality of those intertitles is more in tune with modern times than it seems at first. On the other hand, the intertitles are part of the grammar of those films. They’re linked to the narrative, and, ultimately, to their idea of editing. For example: the duration of each intertitle in the films from that time period interfere with the length of the films as a whole. A cameraman from the silent era who worked in “cavação” films called Tomás de Tullio once stated in an interview that the intertitles were a fundamental part of the cavador’s strategy. The more length a film had, the more money they would earn from those who had hired them to shoot it. So, the cavadores would stuff their films with intertitles in order to make them longer. That procedure obviously had an impact on the editing process, the rhythm of the sequences, and the duration of the other shots. But, when we look at those films today, we only have access to what was left of those copies. Many times, there are intertitles with long texts but very short durations, not by choice of the filmmaker, but due to the passage of time and poor storage conditions. In Que cavação é essa? that inspired some gags, when an intertitle containing some absolutely useless information - such as the one about “the healthy exercise of contemplative leisure” - has a lot more screen time than other intertitles with longer sentences, which go away before you can read the whole thing. The intertitles also provide important information. For instance, they’ll often include the names of the production company and the place where the film was shot. To researchers, that’s vital. In Que cavação é essa? we used that in the intertitles about the fire at the property of Colonel Alexandrão. In those intertitles, unlike the previous ones, both the production company and the filmmaker are named - Prosopopeia Actualidades - L. A. Ramos. This indicates that the first section of Que cavação é essa? is made up from different materials edited together. From that perspective, we have “three films in one”, instead of just two. That’s what happens in a film like Reminiscências (1909) too. It begins in 1909, but some shots were filmed decades later. So, we used all of those references to make the text and the intertitles - the sub-literature typical of a society accustomed to sucking up to powerful people, the phony erudition that mistakes quantity for quality, and the traces of information preserved for posterity in those intertitles.

CL: Can you describe the selection process of actors for Um alegre churrasco na estância do Cel. Alexandrão? Also, I imagine that most of the actors did not have experience acting in other works that emulated the silent period. Knowing this, what was your approach to directing them?

EG: Actually, most of the actors in the film had no experience in acting whatsoever. Most of them were our friends and/or part of the film crew. For instance, the priest was played by critic Gilberto Silva Jr., and the star is played by critic and researcher Luís Carlos Oliveira Jr. The production director, Rodrigo Bouliett, played the “prettiest daughter” of Colonel Alexandrão. Very few were professional actors. We wanted to capture the spontaneity that is typical of non-actors. We did table-reads and lots of rehearsing and ended up with what’s in the film.

LRM: I remember things somewhat differently. Yes, there was an intense period of preparation as Estevão mentioned, and if I recall correctly, at least two or three rehearsals on video, because body language was crucial to the film. I remember we were very concerned about directing the actors in a way that did not emulate a cliché style of silent comedy. Rather, we attempted to emulate “cavação” films, that is, a style reminiscent of the films we had been studying, a style which researcher José Inácio de Melo Souza, when discussing early cinema in a piece published in 2018, called “the commitment of the character being shot on the camera”. José Inácio says that when discussing Reminiscências, the very film that had been one of our major inspirations. We watched it countless times. We even started imitating certain frames and character actions, such as a guest who starts jumping and goofing around for the camera. So, it was important that the actors acted for the camera as they used to in early cinema, and as was characteristic of “cavação” cinema.

On the other hand, our idea was to subvert this “copy” we were crafting, breaking away from the reverence for the documental aspects and making the fictional aspects increasingly evident. In diegetic terms, that “fiction” becomes more and more uncontrollable as the barbecue guests get drunker. From then on, the actors go full slapstick comedy. The rehearsals were crucial to define their gestures and to establish the switching between documentary and fiction, but it was during the shooting that the characters developed, thanks to the costumes designed by Maíra Sala and Rebecca Ramos and to the set where the shooting took place, a century-old farm in Rio das Flores, Rio de Janeiro. We had the honor of working with José Marinho, an actor who worked in such classics of Brazilian cinema as Entranced Earth (Glauber Rocha, 1967), The Red Light Bandit (Rogério Sganzerla, 1968) and The Amulet of Ogum (Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1975). He plays Colonel Praxedes, Colonel Alexandrão’s political rival. Marinho is a great guy and a fantastic storyteller. Another great actor in the film is the amazing Godot Quincas, of Amir Haddad’s Tá na Rua theatre group, who plays the guest that ends up below the table with one of the daughters of the Colonel. Godot is a wonderful, versatile, circus actor. Other fundamental cast members include Cosme Monteiro (Colonel Alexandrão), Sílvia Carvalho (the Colonel’s wife), Érica Collares (Cel. Praxedes’ wife), Lizandra Miotto (the wife of one of the guests) and Otávio Reis (the reporter), who had previously worked in theatre and television. Anna Karinne Ballalai, the production assistant, who has been an actress in theatre and film since her teenage years, plays Godot’s wife. In her scenes, it’s clear how she cared about body language, incorporating the posture of women of that period with a specific, very characteristic way of positioning the shoulders. So, to me, it was a huge learning process in directing actors, experimenting with comedy, working together and dedication. We all had so much fun. Besides, as Estevão mentioned, we worked with many of our dear friends, like Gilberto Silva, Fabián Núñez, Rebecca Ramos, Luísa Marques, Thaís Barreto and Rodrigo Bouillet, some being part of both cast and crew. And Luiz Carlos Oliveira Júnior is a born actor!

I also want to discuss the second part of the film. Although very different from the first half, the performances you see in the second half was very challenging to direct as well. Similar to how the first half of the film featured the iconic José Marinho, in the second part we had the character/homage of the Film Archaeologist, “self-played” by Hernani Heffner, and a special appearance by Severino Dadá. Severino Dadá is a film and sound editor with over 300 films under his belt. He worked on classics such as The Amulet of Ogum and It’s Not All True (Rogério Sganzerla, 1987), and appeared as himself in Tent of Miracles (Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1977), where he shared the screen with Hugo Carvana. In Que cavação é essa?, Dadá offers a very tongue-in-cheek performance as historian Abraão Aragão, an expert in coronelismo.13 Lastly, I want to give a special mention to the character of the “hillbilly” (Luiz Carlos dos Santos) in the scene of the news report. Mr. Luiz was one of the longest serving cleaners at Rio’s Museum of Modern Art, and one of the sweetest, kindest people there. He had no prior acting experience. Yet he was one of our most disciplined actors, very rigorous when memorizing his lines. His line about the fire at Colonel Alexandrão’s place feels like he’s talking about the MAM fires.

CL: At the end of Um alegre churrasco na estância do Cel. Alexandrão, everything gets out of control. There is an angry priest, a big fight breaks out, an orgy, and a dwarf riding the back of a woman. It is at this point that the historical authenticity of the film begins to collapse for the viewer. The complete chaos of the scene allows us to look back at the silent films from that time in a different light. Why is it important that, in the absence of most of the records of the period, we still look to the silent period for inspiration? And what is the value of historical revisions, in this case a comedy, in allowing us to think about this differently?

LRM: I believe historical research is a crucial tool to fight ignorance. It’s no coincidence that today, when neofascism rises in many countries around the world, history is its first target. History is the field where narrative disputes happen, but also the territory for tensions between winners and losers. Revisions are necessary, not to erase or distort, not to spread lies, but to question official versions. This also applies to cinema. It’s not by chance that the historian who is an expert in coronelismo, played by Severino Dadá, states that “Since the beginning, there has always been a complicity between coronelismo and Brazilian cinema”. Since Dadá is a veteran film and sound editor, he knows very well what he’s talking about. Evidently, the dispute over funds and “cultural prestige” chose a few representatives and relegated a large number of films produced in this country to limbo. In the best-case scenario, the outcome is that heritage is “recovered” either by academia or by public authorities, resulting in the “museification” of the past and consequently its “domestication”. And, in the worst-case scenario, the result is the marginalization of everything that doesn’t interest intellectuals, researchers, students, etc. Que cavação é essa? is also about this “cultural colonialism”, which hides the commitment of power to a cultural stratum.

CL: Returning to Restaurare, the mockumentary that follows Um alegre churrasco na estância do Cel. Alexandrão, we immediately noticed that the color tone of the film mirrors a film with deteriorated color. This detail is very important, especially when it comes to a film about preservation. How was this effect created? Was the sequence filmed with already-faded film? What does the use of faded color in this sequence say about the preservation of Brazilian cinema?

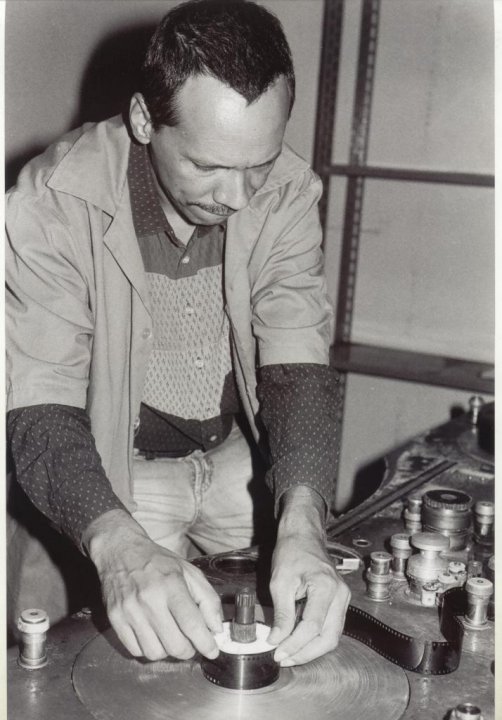

EG: That color was achieved via the research and resourcefulness of our cinematographer, the orientation given to the laboratory, and via “ruining” the film by hand. We didn’t want to deteriorate it digitally, so we did it all manually. That section was scratched by running it through the moviola and projecting it countless times on the projector at the Cinemateca do MAM.

LRM: That was during the editing phase. Image and sound editing, and sound mixing were mostly done digitally. But the work on the texture of the film was created by hand. The black-and-white section, as we said before, was mostly designed and executed during pre-production and shooting. While the film was being edited, we made a rough cut in 35mm. Estevão, William and I “ruined” that rough cut manually, by projecting and scratching it on an old moviola at the Cinemateca do MAM, making grooves in the emulsion by passing the film through two “coils”, among other atrocities. From that positive we made an internegative which incorporated all of those defects. The idea was to copy it without doing a wet gate,14 but this was impossible due to the pattern of the technical process at LaboCine, which reduced a lot the dirt and scratches on the film. For the color section, the faded tones were achieved by color grading. All of that had to be balanced for the definitive copy, and the hard part was exactly preserving the characteristics of the contrasted black and white and faded colors in the same color copy. After our post-production process, the “ontological experience” commonly associated with the photographic image ended up feeling very paradoxical. We shot on 35mm film, then we did away with everything it had to offer, including the impeccable, clean, and high-quality image that was superior to digital images at the time. We used 35mm to carve into the film material itself what actually happened and still happens to our filmic heritage: the loss, the deterioration, and the tragedy of having almost no means to preserve it. And since, diegetically, the “complemento nacional” Restaurare was made in 1974, the fading of the color denounces the neglect towards relatively recent material as well. How many films from the 1970s and 1980s have been lost or are in the process of being lost? By the way, in the waves of destruction of analogical audiovisual material (the transition from short films to feature films, the advent of sound, the replacement of nitrate by acetate), color films suffer more than black and white films; their colors fade away and deteriorate. When it comes to works deemed important by popular historiography, there is still hope of recovering them. But what about those films despised by historians, academics, film critics and official cultural sectors? The faded color in Restaurare calls attention to that contradictory aspect of public policies in support of culture: they speak on behalf of the totality, but only reach a selected group. The irony in Restaurare is that a film about restoration is presented in a state of deterioration, i.e., that film itself needs to be restored! But as it is a typical “cavação” of the 1970s - halfway between an official newsreel and a cultural film - it doesn’t stand a chance. Today, we live in a much more tragic situation: the very notion of “culture” is under attack. In that scenario, everything faces the risk of disappearing.

CL: The spoken narration in Restaurare, in the famous voice of Jorgeh Ramos, is surprising for the viewer because it deals with serious issues (the preservation of Brazilian cinema and the professionals who do this work) with a humorous and somewhat exaggerated cadence. Of course, due to recent events, the preservation of Brazilian cinema is a subject that has been discussed with total seriousness, but what is the importance of looking at these recent events with a tone of humor, and how can comedy be a useful tool during this moment?

EG: Humor is one of the most revolutionary things. Comedy and parody are excellent weapons, as they efficiently trigger critical thinking and reflection. That’s kind of what we did in Que cavação é essa?

LRM: I agree with Estevão completely. Tragedy and comedy walk hand in hand. How can we deal with what is happening in the world today, with this histrionic, cheating far-right spreading absurd conspiracy theories, saying the Earth is flat? Buffoons have risen on a global scale, the democratic fraud of anti-corruption stances is a pretext to promote coups d’etat. All of this is a tragedy, and there’s a deeply ridiculous aspect to that tragedy. We are the targets of that huge publicity stunt called neofascism, which serves to mask the real, eternal tragedy; the plundering by the 1% of billionaires on 99% of the world’s population, especially on the global south. A planetary theft resulting in the extermination of entire populations due to hunger, extreme poverty, and ignorance. The most subversive and intelligent brand of art has always manifested itself through humor and mockery in many other periods which were equally or even more tragic than this one. Humor doesn’t mean lack of seriousness or responsibility. On the contrary. There is nothing more ridiculous than the pseudo-serious taking itself seriously.

CL: The film makes many references to the history of Brazilian cinema in general, from the cavações, the newsreels, the TV reports, the federal censorship cards from the period of the military dictatorship and the pornochanchadas, which are alluded to by the name “Colonel Alexandrão”, a character played by Carlos Imperial in A Viúva Virgem (1972). These references are very specific and even niche, which makes us think that the target audience of your film is aficionados, researchers and preservationists of Brazilian cinema. Is this impression correct?

EG: Certainly cinephiles, researchers and critics who are familiar with Brazilian cinema will catch all the references and quotes more easily. But I think they weren’t intended as our target or main audience. Our intention was to reach as many viewers as possible, and generate interest in film restoration and preservation, and obviously in Brazilian cinema.

LRM: Exactly. I think our film can be read “in layers”. People may find it interesting even if they don’t spot those references. One proof of that is, during the premiere at the Festival de Brasília, the audience in the theater - of course, it was a festival audience, but not necessarily an “erudite” audience in references to the history of Brazilian cinema - laughed from start to finish and gave a long round of applause at the end. Scholars have fun too, as when it was shown in Chile, at the La Moneda Cultural Center, Mónica Villarroel, a researcher on silent Brazilian and Chilean cinemas, and who was the director of the Cineteca Nacional, couldn’t stop laughing. But they can relate to other layers of the film, namely the references to specific genres, characters, styles, films and scenes of Brazilian cinema. In that sense, the film does have a large share of “inside jokes” - but you don’t have to spot or get them to understand the film.

1. Boca do Lixo was an important center of film production in São Paulo from the 1960s up until the late 1980s. Generally, the films produced there were low-budget and of a wide variety of genres. Although usually classified as exploitation, these works had remarkable commercial success among Brazil’s lower classes.

2. “Brazilian Cinema: The Shame of a Nation”

3. “Damned Brazilian Films!”

4. Cidadão Quem? (Citizen Who?) is a pun with Citizen Kane. “Quem” in Portuguese sounds almost like “Kane”.

5. Newsreels produced in Brazil which movie theaters were legally obligated to screen before the main attraction.

6. Memories of an Amnesiac.

7. Literally, “films of digging”.

8. Literally, “diggers”.

9. Literally, “films with plot”.

10. Every film during the military dictatorship opened with the image of a document from the censorship department authorizing the film’s exhibition and informing its age restriction.

11. Documentaries praising Brazil’s natural resources and natural beauty. Splendid cradle, or berço esplêndido in Portuguese, refers to a line in the National Anthem, which states Brazil is “eternally laying in a splendid cradle”.

12. Documentaries focusing mainly on the President of Brazil, as well as national celebrations such as the military parades on Brazil’s Independence Day (September 7th).

13. Coronelismo, literally colonelism, is a phenomenon in Brazil by which a rich political leader rules over a community.

14. EN: Wet gate is a technique used in film restoration to remove scratches.