Abolition – A Brief Introduction to the Film

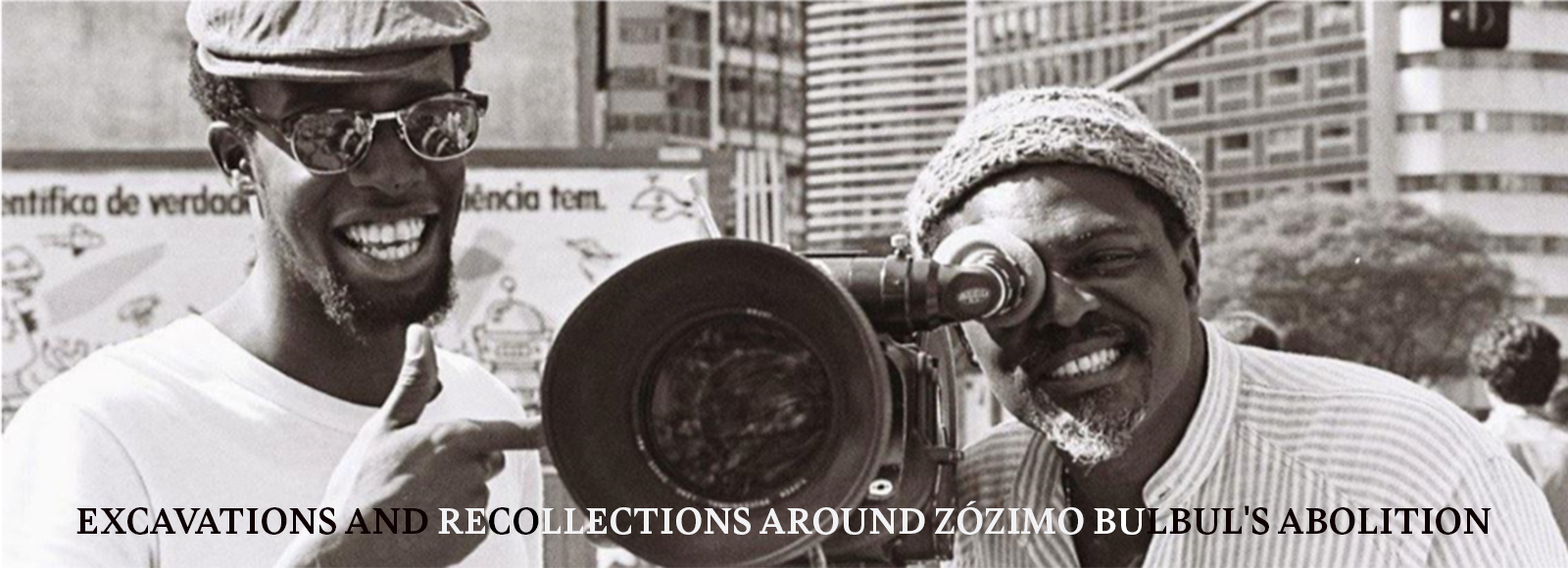

1988 marked the 100th anniversary of the Lei Áurea in Brazil, the legislation that officially emancipated slaves throughout the country. This anniversary sparked conversations about the historical significance of the Lei Áurea, and provoked new criticisms about how far Brazil had come in its treatment of Black people since that historical decree. It was in light of this renewed interest in the Lei Áurea that actor/filmmaker/activist Zózimo Bulbul debuted Abolição (Abolition), his first and only feature film as a director and the product of more than ten years of thorough research. Bulbul intended to use this anniversary as an opportunity to critically reflect on the conditions of Black Brazilians after the emancipation and to demonstrate that the abolition in fact had been a farcical scam. Notwithstanding that there were other films1 produced at that time which covered the Lei Áurea and racism in Brazil, Bulbul’s film explored these topics in a particularly unique way - it was the first Brazilian film shot by a nearly all-Black crew to portray the reflections of Black Brazilians on their own post-abolition condition.

One of the major aspects which made Bulbul’s filmmaking process stand-out from the other works that explored the conditions of Black people in Brazil is the breadth of locations which the film covers. The crew of Abolition traveled with their camera through sites and cities that remain crucial to the development of Afro-Brazilian culture. These included Bahia and Pernambuco (Northeast), Manaus (North), Rio Grande do Sul (Deep South), and São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (Southeast). Another of Abolition’s achievements is the way that Bulbul managed to shed light on a diverse array of situations in which Black people were living. For example, the crew captured interviews with key icons from the Afro-Brazilian community, such as Abdias do Nascimento, Lélia Gonzalez, Carlos Medeiros, Beatriz Nascimento, Grande Otelo, Joel Rufino dos Santos and Benedita da Silva. In the film, these interviews are occasionally shown on-screen sharing perspectives informed by their own Blackness, but in other moments, voices from the interviews materialize as the camera shifts its attention to Black bodies that are, despite being part of our social urban fabric, perpetually rendered invisible throughout our history: workers, the homeless population, the impoverished living in the slums, the street artists and so on.

Why Abolition?

I’ve been involved with the work of recuperating Abolition’s historical materials on a daily basis since I began the graduate studies program in Communications at Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro two years ago, and I recently concluded the program with a master’s dissertation on the film. As I began conducting research for my dissertation, I encountered a scarcity of information on Bulbul’s lone feature film. There are only a few academic works that cover the cineaste’s life—all of which barely discuss Abolition—and I had not come across any work that provides it with a thorough analysis. This makes clear that despite receiving awards at Brazilian film festivals, as well as overseas,2 the documentary went on to make only a minor impact on the world of film academia. Noel dos Santos Carvalho, a film teacher and researcher from Universidade de Campinas (UNICAMP), attests to how the film was met with indifference: “With its 150 minute duration, Abolition did not find approval with the audience. Not even among Black people. The conversation around it was limited to a small circle of intellectuals and Black activists”.3 Carvalho’s testimony poses several questions: Why was Abolition seen by so few people? Why was its impact so minimal? What is the film’s legacy among today’s Black researchers?

Aside from investigating these questions, this article will bring together some of the memories and recollections from the Abolition film crew that I gathered while interviewing them for my master’s thesis. These memories and recollections are vital towards gaining an updated understanding of the film today, as it is important to appreciate that Abolition was the universal effort of many forces of Black creativity. In the eyes of researcher Heitor Augusto (2018), investigating the creation of Abolition allows us to comprehend the nuances of a film that was conceived and executed by Black creators during a moment when new ideas, projects, and perspectives, both in Black Brazilian cinema and intellectual thought at large were emerging. The core crew members of Abolition were/are trailblazers in that they executed roles that were unprecedented for Black professionals. However, perhaps even more importantly, they reclaimed the legitimacy of their enunciative position and their right to tell their own stories. From behind the camera (or even because of it) this crew contributed to the theorization and structuring of Black cinema, a field that was practically nonexistent in Brazil at that time.

In conversation with the film crew

On January 28, 2020, on a hot Rio de Janeiro afternoon, I first encountered Vantoen Pereira Jr. Pereira Jr. played a decisive role as a facilitator on Abolition’s production, and he still works to promote the film and fights to preserve its memories. In my conversation with Pereira Jr., he started off by bringing me back to the origin of Abolition, towards the earliest days when Bulbul first began developing the project.

According to Pereira Jr., Abolition began to take shape around 1977 on an immersive trip that he and Bulbul took to Búzios, a city located in Rio de Janeiro’s lake areas. He recounts that Bulbul, who had just returned from a self-imposed exile,4 rented a house at Rasa beach and immediately began writing. Bulbul set out to incorporate some of the social, historical, and aesthetic investigations to be found within his previous films Alma no Olho (Soul in the Eye, 1973) and Dia de Alforria (Emancipation Day, 1981). In addition, Bulbul had gathered new ideas and information throughout his journey through Africa, Europe and the United States, and he was eager to incorporate this into a new project. While working in Búzios, Bulbul used a typewriter to register his memories and recollections from this journey.

Then, in 1986, after nearly a decade of research during which he was working towards a final draft of the screenplay, Bulbul put together the crew that would bring Abolition to life. From the very beginning, Bulbul expressed his predilection for having an all-Black crew since he believed that only professionals from the Black community would be able to bring the specific perspectives needed to make the film. However, though the race criteria was important to Bulbul, it was not the determining factor as to who would get hired to work on Abolition. While I will touch on this point further on, I find it imperative to now introduce eight crew members from Aboliton and explain the important role they played in its production. But before delving into these testimonies, I must stress the importance of analyzing Abolition through the point of view of the professionals whose jobs aren’t typically perceived with the same level of prestige enjoyed by screenwriters and directors (both roles personified by Bulbul in the case of Abolition). The conception and the construction of a work of cinema such as Abolition is necessarily based on the input of a collective, and by bringing to light the voices and experiences of the crew members on this predominantly Black film set, we are able to delve deeper into the film, following the tracks left by their accounts and collective memories. We can then begin to comprehend how the need for collectivity, or “aquilombamento”5 stems from the desire to forge a space where people can show each other affection, actively listen to one another, forge new connections, and discover identities.

Deusa Dineris

The first crew member that I would like to highlight was the only Black woman to be a part of the making of Abolition, Deusa Dineris. Dineris was one of the film’s most important contributors and she was invited to join the project in 1986, right before shooting started. At the time, she had been working as an advertising executive for the advertising company Momento Filmes.6 During the film’s funding stage, the producers identified the need to create a co-production in order to compete for a grant from Embrafilme, and therefore Momento Filmes acted as the co-producer. Through this co-production, Dineris got involved with the film; but she explains that her involvement only happened by chance, since she wasn’t working in cinema at that time.

Dineris and Bulbul’s first encounter took place at Momento’s headquarters. She knew very little about Abolition, only that the crew was made of eleven men and one Black woman, Anya Sartor, who was expected to work as the continuity supervisor despite having a previous career in acting. Just before shooting began, Sartor had to withdraw from the project for personal reasons. This left a major gap within the production crew, and there was now the challenge to find another Black woman who could fill in for Sartor. Bulbul believed it was necessary to have a racialized feminine perspective as part of the crew and to the surprise of Dineris, Bulbul and owner of Momento Filmes (Jerônimo César) decided to invite her to fill the position vacated by Sartos. Although Dineris initially showed reluctance in accepting this offer due to her lack of experience in the film industry, in the end, Bulbul managed to convince her to work on the film.

Image From the collection of Deusa Dineris

In our interview, Dineris recollected that being the only Black woman on the crew was not a challenge for her, as she had three prior experiences working for publicity agencies where there were no other racialized women on staff. However, the real challenge for her was accepting a job that she had no previous experience in. By working on the documentary, she likely became the first Black woman to serve as a continuity supervisor on a Brazilian film. The fact that it took so long for a female to fill this role may come as a shock to many. But it is important to keep in mind that it was only in 1984 — 4 years before Abolition — that the first feature length film directed by a Black Brazilian woman hit the theaters. This was Adélia Sampaio’s Amor Maldito (Cursed Love).

In a film industry dominated by white men, the presence of Dineris was of fundamental importance to Abolition. Throughout the interviews I conducted with the film’s eight crew members, each emphasized that the presence of Dineris on the predominantly male film set allowed the film to be less oriented towards the male-gaze. However, during the production of Abolition, there remained the all too common gender-oriented working dynamic that privileged men. Dineris recounts that because the crew was so small, she accumulated new tasks beyond her initial role as the continuity supervisor, becoming actively engaged as assistant director and producer. “While the crew would go to the bar after the shooting, I’d stay indoors working and getting everything ready for the next morning”, she recalls. Such unbalanced divisions of labor reveal that there was still gender stereotyping throughout the making of Abolition.

Despite these obstacles, Dineris reveals that being part of the film had a direct influence on the growth of her own budding racial identity. It is no coincidence that, after working on the documentary, Dineris decided to quit the advertising business and become engaged with the Black struggle, eventually launching an event-production company7 solely dedicated to promoting Black artists.

Dineris has preserved both her personal memories and memorabilia from the period of making Abolition. On the day of our interview, she brought pictures, a book autographed to her by the journalist Edmar Morel (who is featured in the film), and a publicity folder produced for the release of the movie. She passed that folder onto me as a gift, remarking on the importance of sharing it with future generations in order to show the ways in which Brazilian films were advertised during the pre-Internet era.

My conversation with Dineris and the act of investigating her role in the film was one of the most thought-provoking parts of my research, and her narrative is crucial towards understanding what working dynamics were like on the film set of Abolition. A Black cinema — that is, a cinema made by Black creators — must be mindful of intersectionality. In its efforts toward building a nearly all-Black crew, Abolition contributed to larger efforts of inserting Black professionals in the film industry, all the while reproducing gender stereotypes and sexist microaggressions in its division of labor.

Vantoen Pereira Jr.

Coming from a career in photography, Vantoen Pereira Jr. joined the crew of Abolition with former experiences in the arts. But it was through Bulbul, who was like an uncle and godfather, that he first began to learn about cinema. Since Bulbul never had children, he and Pereira Jr. were able to forge something like a father-son relationship. I would like to stress that this close relationship, as well as Pereira Jr.’s previous experience as a still photographer for well-regarded directors such as Nelson Pereira dos Santos, José Medeiros and Roberto Farias, helped create a familial atmosphere on the set of Abolition.

The official role that Periera Jr. had on Abolition was assistant cinematographer alongside DP Miguel Rio Branco, but his involvement in making the film went beyond that—he witnessed and contributed to early research in Búzios, and he read over Bulbul’s initial screenplay drafts. Bulbul also had a profound influence on Periera Jr., as he was able to develop his photographer’s eye while working on the set of Abolition. Bulbul changed my "understandings around image-making, visual poetics and working practices”, Pereira Jr. said. During our conversation, Pereira Jr. walked me through each step of Abolition’s filmmaking process. He made sure to reiterate that Abolition is a very meaningful film, and insisted that we can glean much more from it than what was initially grasped during the time of its release.According to him, it was a film for the future, to be explored by generations to come.

Pereira Jr. is not merely a source for valuable archival material related to the film (as he has preserved photographs and documents from the film sets), but he also serves as a precious carrier of memories related to Abolition’s production previously known only to him. Of these memories, Pereira Jr. recollects that Bulbul often stressed the “importance of family” throughout the filmmaking process; according to him, Bulbul emphasized this idea because he believed that it was an important force in providing a reconnection and reconstruction for Black families who were torn apart as a result of centuries of slavery. Pereira Jr. also discussed how community building and the power of encounter were key ideas that influenced Bulbul throughout his career, even claiming that one of Bulbul’s intentions with Abolition was to explain why thousands of Black families were separated and decimated since the Lei Áurea.

Severino Dadá

Severino Dadá worked as the editor for Bulbul’s second film, the documentary Aniceto do Império em dia de Alforria? (1981). In our conversation, Dadá recalled that he was first to be formally invited by Bulbul—with whom he had been friends since the 1970s—to work on Abolition. The two shared thoughts throughout the entire pre-production process, from providing input on the screenplay to helping Bulbul choose the interviewees. Every member of the crew who worked on Abolition is reverent towards Dadá, who is famous for his encyclopedic knowledge, and recognized for his fundamental contributions to Brazilian cinema. Dadá is one of the most active film editors within the history of Brazilian Cinema, his credits amounting to more than 300 films. His fondness for Bulbul was visible when he spoke about Abolition, as he emotionally recalled the intimate friendship which he had with the filmmaker that contributed to this crucial chapter in Brazilian cinema history.

Before working on Abolition, Dadá had already enjoyed a prolific career as an editor, having worked with prominent Brazilian directors such as NelsonPereira dos Santos and Rogério Sganzerla. A native of Pedra, a small city located in the backcountry of Pernambuco state in the Northeastern Coast of Brazil, Dadá began his career as a radio announcer. However, he soon migrated to cinema once he joined the independent film club circuit. His life-trajectory soon intersected with Brazil’s immediate political history as he was incarcerated and tortured by the military during Brazil’s military dictatorship8. Both Dadá’s background as a native of Pernambuco and his political activism were vital to the ways in which he contributed to Abolition. Also, as one of the few white crew members, his political convictions and perspectives as a nordestino9 offered a fresh perspective to the film.

One of the many stories Dadá told me recounts the day that Bulbul was informed of Embrafilme’s decision to fund Abolition. The director invited the editor to São João Batista Cemetery in Botafogo on the South Side of Rio de Janeiro, in order to deliver an ebó, which is a type of offering that is part of the tradition of various Afro-Brazilian religions. The ebó was being delivered by Bulbul to express his thankfulness for receiving the awarded grant that would make the production of the film possible. As they entered the cemetery, a police car that was circling in the vicinity approached them. One of the officers stepped out the vehicle, and he recognized both Dadá and Bulbul. That officer was Paulo Copacabana, who had worked as an actor in some films, including Roberto Farias’s O Assalto ao Trem Pagador (Assault on the Pay Train, 1962) and J.B. Tanko’s Bom Mesmo é Carnaval (Carnival is Truly Good, 1962). As he questioned them for their reasons of being in front of the cemetery late at night, Dadá and Bulbul explained they were about to execute a thanking ritual. Copacabana then proceeded to put them both inside the police vehicle and drove them to a nearby bar in order to celebrate the film grant; they all sat together—Dadá, Bulbul, Copacabana and another cop, who eventually paid the bill.

Another less humorous anecdote recounted by Dadá involved Pelé, elected in 1980 as the Athlete of the Century by the French paper L’Equipe. As an international superstar and the Black symbol of soccer at the time, Pelé was invited to be interviewed and share his thoughts on racism in sports. Pelé declined the invitation, explaining that he believed racism did not exist in Brazil. Disappointed with his stance, Bulbul and Dadá were forced to look for another figure to be interviewed in the film, someone who had a more critical perspective on racial issues in sports, especially in soccer. They ultimately invited Paulo Cézar Caju, who was known throughout his career as a lone critical voice of racism in soccer. Caju promptly accepted being interviewed for the documentary, where he devoted harsh criticisms towards Pelé due to his lack of engagement in the Black struggle. The response to this was immediate: Pelé’s lawyer contacted Bulbul to communicate the athlete's wishes to have the interview removed from the film, as it tarnished his image. Despite such extreme pressure, Caju’s opinions remained in the final cut.

This situation illuminates the difficulties one faces when trying to begin a conversation about racism in Brazil. What Bulbul encountered with Pelé is a common situation in Brazil: eitherBlack figures refuse to acknowledge structural racism or they give the packaged, standardized answer that, despite the existence of prejudice in society, they themselves were never the target of it. I’m left to wonder how painful it must have been for Bulbul to hear from Brazil’s most important athlete that racism is a fiction by which he was never hurt. The episode serves as a clear testament to the obstacles that the film had to overcome in providing a more truthful representation of Black life in Brazil.

Alexandre Tadeu, Edson Alves, and Biza Vianna

Alexandre Tadeu, a film electrician, met Vantoen Pereira Jr. when they worked together on Roberto Farias’s Pra Frente Brasil (1982) and they quickly became friends. Soon thereafter, Tadeu met and became friends with Bulbul, as they both frequently attended the bars and night life of Lapa, a historic neighborhood in downtown Rio de Janeiro. Their favorite place to meet became “Tangará”, a tavern where they would exchange new ideas about cinema. Tadeu recalls that they never directly talked about Abolition during those encounters and that he only became familiar with the project when editor Severino Dadá took Bulbul to the offices of Memento Filmes. As a staff member of Memento Filmes, Tadeu naturally became involved with the production of Abolition, offering the crew support with company rental equipment. Tadeu also remembers that during post-production, he would accompany Dadá and Bulbul in the cutting room, and after a long shift of work they would head to São Salvador square, in Laranjeiras, to discuss all of the editing choices of the day.

Edson Alves, aka “Edinho”, was a professional lighting technician and electrician who had a brief stint working on the set of Abolition for ten days. His work can be prominently seen in the fictional sequences in early half of the film.10 However, despite the fact that Ediho only worked on the set for a short period, his presence was very important to Deusa Dineris, who recounted in our interview that she learned many of the ins and outs of a film set from Edinho. I would like to emphasize this relationship between Edson and Dineris it reflects the importance of aquilombamento on the making of Abolition. It was made evident throughout the interviews I conducted that the sense of shared identity and communion that Abolition’s production offered the crew was a respite from the previous experiences that they had in white-dominated working environments which precluded this form of collectivity.

Bulbul’s widow, Biza Vianna, shared with me that the couple were forced to break the agreement they had made to never work together, especially on film shoots. She joined the project at the last minute because it urgently needed a costume designer for the aforementioned fictional sequence in which Princess Isabel reads the proclamation of emancipation. Vianna had a career working in fashion and theater, so she joined the crew and was responsible for both the costume of the fictional characters and the clothing of the crew members who would eventually be shown on-screen in key sequences. Vianna used Zapatistas Army of National Liberation as an inspiration for dressing the crew as a way to suggest an image of a Latin-American resistance. She considers her role on the film to have been small, but other members of the team such as Pereira Jr. and Flávio Leandro think otherwise, stressing the importance of Vianna as both a professional and Bulbul’s partner, whose legacy she oversees today.

Miguel Rio Branco

Lastly, it is paramount to explore the role of cinematographer Miguel Rio Branco, the only white man on the Abolition shooting crew. Prior to joining the production, his work as a photographer had shown a predilection for popular culture, as can be seen in the series Maciel (1979). Maciel documents the precarious conditions in the oldest areas of Pelourinho, a historic neighborhood in Salvador, Bahia. Years later, Rio Branco directed Nada levarei quando morrer, Aqueles que mim deve cobrarei no inferno (1985), a key short film in his career.11 By the time he worked on Bulbul’s documentary he already was a nationally and internationally acclaimed artist, especially praised for his photography. In August of 2019 I travelled to Araras, a city on the mountains of Rio de Janeiro, to interview Rio Branco and record his memories from working on Abolition. Rio Branco did not maintain close contact with Bulbul and the rest of the crew after shooting completed, and therefore his thoughts on the final version of the film are enigmatic. According to Biza Vianna, Rio Branco distanced himself from the documentary upon its completion, “never [making] any effort to learn about the film”.

Although Bulbul had wanted to assemble an all-Black crew, he faced challenges when it came to choosing a DP, since, according to Dadá and Flavio Leandro, there were very few Black cinematographers in Brazil. Bulbul believed that Rio Branco’s vast oeuvre12 of photographing Black bodies would provide him with the necessary experience to shoot Abolition. When I brought this up to Rio Branco during our conversation, he disagreed that this was the reason that had led Bulbul to choose him as DP. According to him, “As long as you have the ability to gaze and possess technical knowledge, you can photograph any type of body, black or white”. I believe that this statement deserves further scrutiny.

Rio Branco’s understanding is opposite to that of Eustáquio Neves, another well-regarded Brazilian photographer who has discussed his struggles during the 1980s to find the right camera equipment appropriate for capturing different shades of dark skin. Neves became known for having developed alternative and multidisciplinary techniques to manipulate film negatives and positives to suit this purpose. According to Neves:

Lighting standards weren’t developed having darker skins in mind, but rather to the Caucasians’. It used to be very difficult to photograph a Black woman in a white wedding dress. One ended up having to lighten the skin instead of portraying the color as it was originally. I used to believe that I didn’t know how to photograph, until I realized the issue wasn’t me, but the standards.13

Neves’s statement reveals that it wasn’t just a matter of having a pure ability to take good photographs, since properly photographing Black bodies involved overcoming different technological factors and social norms that were created by the photographic industry and which went unchallenged for many years. As Abolition would be a film that mostly rendered Black bodies, the aesthetic choices behind the film’s cinematography was a matter taken into serious consideration by Bulbul. Not only was Bulbul forced to reckon with the technical limitations of producing an authentic image of Black bodies, but he also had to consider the cinematographer’s subjective gaze. It was therefore necessary to count on a DP who could be sensitive to these issues. Despite his declared indifference to the systemic prejudices of technical cinematography at the time, Rio Branco’s success with Maciel led Bulbul to believe that the photographer could deliver an image similar to what he had in mind. Despite the disparate choice, the partnership between Bulbul and Rio Branco yielded beautiful results, as the film went on to win the Best Cinematography award at the Festival de Brasília. Rio Branco revealed that he was surprised to receive this award, since he believed that the film’s strengths were its research and screenplay, particularly the unprecedented coverage of the emancipation of slavery by Black creators.

There was also a disagreement between Bulbul and Rio Branco over Bulbul’s decision to pre-conceive the form in which the film would take, as this implied that there would be very little room for debate and experimentation in the film's mode of visuality. Of course, this “preconceived form” was in fact a reflection of Bulbul’s clarity of vision for Abolition. The film was the very definition of a passion project for Bulbul, who therefore knew how he wanted the film to look and what form of construction it should take. For a white cinematographer such as Rio Branco who was used to having greater autonomy in the decision-making process on the set of a film, being relegated to the role of an observer felt like a disappointment. The friction between Rio Branco and Bulbul, of which remnants can still be felt today, reveals the social hierarchy of race within working relationships, and how it was and still is difficult for white people to take directions from Black professionals.

In fact, as a white man, Rio Branco was amazed that he was even invited to work on Abolition.14 During our conversation he expressed that: “In the United States they would never cast me as the DP of a film like this, and my presence in it shows that we Brazilians enjoy the possibility of a bigger interracial relationship than other countries”. However, when we look at the history of racial disparities within the Brazilian film industry, they reveal that Brazilian cinema has always been a predominantly white industry. A thorough examination of the Brazilian film industry sponsored in 2017 by GEMAA (Study Group for Affirmative Action)15 revealed a severely segregated landscape throughout the history of Brazilian cinema. GEMAA’s study looked at the highest grossing Brazilian films between 1970 and 2016. Their findings revealed that gender and racial inequality have always been the norm within the Brazilian film industry. The study claims:

Between 1970 and 2016, the highest grossing films (works seen by more than 500 thousand people) were predominantly directed by white men (98%). We couldn’t identify a single director who was a person of color, though we must state that 13% of the titles couldn’t be analyzed due to lack of data. When it comes to gender, we noticed a very low number of women working as directors: only 2%. And none of them were Black.16

When analyzing the screenwriters of those titles, “only 8% were women and the only Black woman we could identify in the sample was Julciléa Telles, who was the co-writer of the sex comedy A Gostosa da Gafieira”.17 Despite the fact that GEMAA’s study only took into consideration feature-length fiction films, I believe the landscape wouldn’t be much different had other modes or formats of filmmaking been considered.

There is one final element related to Bulbul hiring Rio Branco that is important to note. In my conversations with the film crew, they revealed that Bulbul saw this hiring as a strategic decision: by inviting in a member of the Brazilian elite,18 Bulbul was inverting the common social hierarchy in which white men had all of the decision-making power on a film set. When we consider the hiring from this perspective, we see the irony in Bulbul’s choice. It’s surely no accident that Rio Branco is the only crew member that is never featured on-screen throughout the film. This indicates that the self-reflexivity of Abolition was not intended to include the position of its own DP.

In concluding my analyses of the roles that each crew member had on Abolition, I would like to highlight one last component related to the personal dynamics of the crew. Throughout the interviews I conducted, each crew member mentioned the importance of “tavern talk”, an expression of Bulbul’s that was meant to be applied and understood as an ethical value. Cultivating a bohemian lifestyle was seen by Bulbul as an important ritual that one must always engage in, and even include it within work processes. Upon listening to the crew’s memories of working on the film, I soon realized that many decisions that went into the construction of the film were made during encounters at bars and taverns. It is worth noting here that the word “bohemia”, beyond its connotations of pleasure and entertainment, also connotes a social-cultural practice that takes into account lived experiences from different subjectivities. There are political implications to be gleaned when considering that a nearly all-Black crew was circulating and, to a certain extent, occupying areas of Rio de Janeiro, a city that still to this day disguises its hostility towards Black bodies. Congregating within these spaces and sharing discussions among one another certainly played a significant role in the film’s construction and in the way that the crew bonded throughout the filmmaking process.

The Commercial Distribution and Further Legacy of Abolition

Abolition was finished in 1988 after extensive periods of research, production, and post-production. Bulbul’s expectations for the film were high, as he had just completed a work of unprecedented depth that was to be released in the same year that marked the centennial of the Lei Áurea, one of the most important moments for Brazilian Black activism in the 20th century. This was a period of intense conversations and debates around many topics involving racial issues, and the representation of Black people in film and television was among the most discussed. Bulbul’s goal was to make a major contribution to that conversation.

Everyone involved with the film hoped Abolition would spark a meaningful and broad conversation around these issues, and they all hoped that the film would be released in the commercial circuit and screened at various film festivals. One of the reasons that the crew hoped the film would achieve this success is summarized by researcher Noel dos Santos Carvalho, as he claims the documentary “objectively manifests the political stances taken by Black activism since the 1970s”.19 Bulbul believed Abolition would also serve as a counternarrative to other contemporary productions around the centennial celebration of the emancipation. Bulbul made sure to detach himself from any production that he believed posed an opposition to his political values, which, according to Carvalho, led him to refuse taking part in a special production by Rede Globo, Brazil’s biggest communications conglomerate, that would celebrate the anniversary. He claimed, “There were artists and Black activists who pressed me to be there. But I don’t work for free for [Globo’s founder] Roberto Marinho. And besides, I found their show a demagogic piece”.20

Bulbul was completely engaged in securing a commercial run for his film, and his widow Biza Vianna recalls how releasing the documentary became one of the biggest frustrations of his life. Abolition did not resonate with the public nearly to the extent he had hoped for. When I asked the crew and Vianna about why the film was received so poorly, they all referred to a boycott coming from certain players and intelligentsia within Brazil’s film circles, and within Embrafilme, the state-owned company responsible for distributing the documentary.

The topic of Brazilian commercial film distribution was analyzed by researcher Patrícia Selonk, who highlighted the role played by Embrafilme as the main sponsor of our films since the company’s conception in 1969 until its implosion in 1990. According to Selonk, Embrafilme provided a certain level of infrastructure and helped forge a new public interest in Brazilian cinema despite the fact that the market was dominated by foreign studios. However, Embrafilme’s practices were also met with criticism from filmmakers who made the accusation that they prioritized certain films while delaying the commercial release of others:

Júlio Bressane and Rogério Sganzerla were critical of Embrafilme for its close ties with specific producers, such as Luis Carlos Barreto. The company’s chief of distribution, Marco Aurélio Marcondes, would justify his practices on the basis that these filmmakers’ works were underground, therefore wouldn’t be the recipient of a major financial injection by any distributor.21

Although the fundamental role of Embrafilme was to sponsor new works of Brazilian cinema, they often made insufficient efforts to distribute the films that they had funded to make. When analyzing Abolition’s commercial run – or lack thereof – the mindset of those at the head of Embrafilme becomes evident. The crew members I’ve interviewed assert that the documentary was never officially released, and its distribution was limited to screenings at film festivals in 1988, among which were the Festival de Brasília and the Cine Rio Festival.22 During the latter festival, Vianna recollects that the film was not programmed as part of the main section, in which films were projected within an actual film theater. On the contrary, Abolition was only programmed in a sidebar of outdoor screenings. Similarly, the first showing of Abolition was at an outdoor screening in Bulbul’s hometown, the affluent neighborhood of Ipanema. The screening took place at Nossa Senhora da Paz square and was packed with many viewers and guests. One of them, according to Vantoen Pereira Jr., was a young Spike Lee, who was in Brazil promoting his second feature, She’s Gotta Have It.

Edinho Alves and Alexandre Tadeu explain that the film crew ended up taking the task of distributing the documentary into their own hands. They improvised a communications strategy, which included spreading posters around the city and booking screenings outside of Rio de Janeiro. Regardless of their initial success in attracting a large crowd to the film’s premiere, Abolition would go on to barely make an impact on the national film market, never enjoying an official commercial run.

Beyond Embrafilme’s active disengagement from helping to distribute Abolition, another factor that contributed to the film’s poor reception is its duration. The current cut of Abolition is two hours and thirty minutes long, and according to Flávio Leandro, this negatively influenced the audience’s ability to embrace the work. The length of the film proved to become a point of contention between Bulbul and his crew. The first cut was over four hours long, and it required a strenuous effort on the part of the film crew to convince him to acquiesce to a shorter version.

Therefore, without adequate institutional support or the financial means to distribute Abolition independently, the documentary was only shown overseas years after its completion:

Abolition was awarded at Festival de Brasília ’88 and it also won something in Cuba and while I was at a film festival there, I was invited to show the film in New York. I was also awarded there, but in my country not even a line was written on the papers on the film and on the awards. I came back to Brazil profoundly sad with the international recognition the film enjoyed, while here nothing happened, neither with the film, nor with me. I expected to be known, to show the film, I wanted to be out there talking about it, discussing both Brazilian film history and the topics touched by my documentary, but in the end it felt like “shut up, nigger, there’s no racism in Brazil! You’re making these things up!” That brought a great deal of frustration.22

The lack of acknowledgement and financial support for Black filmmakers, even those with proven abilities such as Bulbul, caused the cineaste to take a long hiatus as a director. Only in 2001, when he received a grant from Rio de Janeiro’s state production fund dedicated to short films, did he produce and direct another film, the documentary Pequena África (2001).23 In the same year he also finished Samba no trem (2001).24 Despite not working as a director between 1988 and the early 2000s, Bulbul’s life was filled with remarkable experiences. He would go on to cement his important legacy with the creation of the Centro Afro-Carioca de Cinema (Afro-Carioca Center for Cinema). The frustrations that Bulbul experienced throughout the release of Abolition drove him to take a personal journey that resulted in the idea to create a space where he could show his films as well those of other Black filmmakers.

In 1997, when he had the opportunity to travel to Burkina Faso to participate in the 15th Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou,25 he realized how much his work was recognized and appreciated.

(...) They gave me warm reception. From the airport to the hotel and throughout the duration of the festival, I was respected as a Black Brazilian, as a filmmaker and as a guest. When I saw all those people at the opening ceremony, more than 20 thousand people gathered at a track field, it moved me. The difference between “FESPACO” and other film festivals around the world is that over there regular people from Burkina and the neighboring countries engage with the event, while “Cannes” or even “Festival do Rio” are held to the elite, not to the people.26

Experiences such as those at FESPACO helped to forge Bulbul’s conviction that a new landscape for Brazilian cinema needed to be established. It wasn’t enough to just make films, there was also an urgency to create a circuit for the screening of Black-directed films. As Abolition’s distribution saga illustrates, Black creators faced a double impediment: even when they were able to overcome the difficulties in completing their films, they still had to fight a distribution and exhibition system that was specifically designed to exclude them from theater screens.

Final considerations

In conclusion, I wish to share with you my individual trajectory throughout the course of conducting research for my Master’s thesis. I consider myself a member of a generation of Black youth that have been promoting long-silenced conversations and reclaiming the memories of those who have paved the way for us to finally occupy spaces to which we have been historically denied. The very possibility of being able to conduct my research was the result of those who have paved the way before me. In my eyes this is the true legacy of Abolition: providing greater esteem for Black culture, giving it the regard and study it deserves, and scrutinizing history for the purposes of making intellectual contributions to society at large. As an art form, cinema is a tool that has the power to affect, to move and to create new ways of seeing and understanding. To be able to watch and identify myself in a documentary made 32 years ago illustrates how cinema can be timeless.

This change was made possible by the social policies implemented throughout Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s and Dilma Rousseff’s administrations, as they pushed for programs aiming to fight for equal access to education. The implementation of race-based affirmative actions and the establishment of programs such as Universidade Para Todos (PROUNI, University for All,)27 provided an important aid that allowed a younger Black and unprivileged generation to go to college, graduate and find better opportunities within the job market. My own trajectory intersects with these policies: as a recipient of a scholarship from PROUNI, I managed to finish college and subsequently enroll in an advanced studies program. At that program, I was inspired to conduct the research from which this article stems.

It’s also important to highlight the expansion of broadband internet throughout new territories in Brazil, as well as the arrival of cheaper technological devices that enabled the rising of new voices from underprivileged areas of Brazilian society. These voices are now creating radical works of art that continue to push forward the conversations kept alive by Bulbul and others. I would also like to take the opportunity to acknowledge that I was only able to start my research on Abolition due to an unofficial, sole hyperlink that is available on a Facebook page devoted to the film (@AbolicaoZozimoBulbul). In the early stages of my research, before I was provided with an official link to the film, that page allowed me to re-watch the documentary multiple times, thus structuring the analysis I’ve developed during my master’s thesis. That same hyperlink, and , and the video available on Cinelimite, makes it possible for Abolition to be seen by a wider range of people. Bulbul’s accomplishment is a work that must be revisited today so that we can finally acknowledge it as an important and unique historical documentation of our country and a pioneering work of Black cinema throughout the world.

1. For example, Eduardo Coutinho’s documentary Fio da Memória (1988) and Abolição, a miniseries written by Wilson Aguiar Filho for TV Globo.

2. Best Historical Research and Best Cinematography at the 21st Festival de Brasília do Cinema Brasileiro in 1988; Best Documentary at the New York Latino Film Festival in 1989; and Best Poster at the 11th Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano, in 1989, Havana, Cuba.

3. Noel dos Santos Carvalho,. “O Produtor e o cineasta Zózimo Bulbul – o inventor do CinemaNegro Brasileiro”. Revista Crioula, São Paulo, n. 12, nov. 2012,p. 18.

4. In 1974, Bulbul attempted to obtain permission from Brazil’s censorship bureau that would allow him to screen his latest film, “Alma no Olho”. However, he was called upon by the military to be interrogated. “They were suspicious about the film and its authorship, so they requested Bulbul to decode the images, since they thought there was some implicit subversive leftist message. After this event, which lasted for days, feeling psychologically pressured by the general political atmosphere, and fearful of the repressive state forces that were then persecuting artists, he traveled to New York intending to remain away from Brazil for a while.” (CARVALHO, 2012, p. 14)

5. The “quilombos” (“maroon communities”) were constituted, according to Beatriz Nascimento, as spaces for resistance, for political organization and for reframing cultural and social values for Black people and their descendants. “Aquilombar”, which in English could be interpreted as “gathering ourselves as a quilombo”, is a political and epistemological notion that hase merged specifically out of the cultural-historical Afro-Brazilian process. See Another Gaze’s discussion of the concept here.

6. Momento Filmes is a production company located at Laranjeiras, a neighborhood at the South Side of Rio de Janeiro. The business operations of Momento Filmes were mostly focused towards advertisements, but they also partnered in the production of several short films and some feature films, particularly from independent filmmakers. Additionally, Momento Filmes rented out film equipment.

7. Among the events produced by her company, Dineris emphasizes a party called “100% afrobrasileiro” (“100% Afro-Brazilian”), which was dedicated to promoting Black artists who weren’t part of the mainstream Rio de Janeiro cultural circuit.

8. Brazil was being ruled under a military dictatorship between 1964 -1985

9. Besides serving as a geographical marker, “Nordestino” also represents a specific cultural and social identity that relates to characteristics specific to the Northeast side ofBrazil. Abolition documents some of the cultural expressions of the “nordestino” identity, such as the “Teatro de Mamulengo and the “Emboladores de Recife”.

10. These fictional scenes took place at the house of the Marquess of Santos in São Cristóvão neighborhood, located on the North Side of Rio de Janeiro.

11. This film belongs to the Inhotim Museum’s collection in the state Minas Gerais.

12. Miguel Rio Branco is a photographer who documented areas marked by violence, degradation and neglection by the state. The majority of the population in these areas, due to reasons made explicit by this article, were Black.

13. Velasco, 2016, n.p

14. Rio Branco was with the crew members for the majority of the shooting, but had to withdraw from the film when they were shooting the scenes at the Palace of the Marquess of Santos, due to health complications related to hepatitis that was aggravated by his heavy alcohol consumption during the filming.

15. The full report can be read at: http://gemaa.iesp.uerj.br/boletins/boletim-gemaa-2-raca-e-genero-no-cinema-brasileiro-1970-2016/ (only in Portuguese)

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Miguel Rio Branco is the great-grandson of the Baron of Rio Branco and the great-great-grandson of the Viscount of Rio Branco, besides being the son of a diplomat.

19. Noel dos Santos Carvalho,. “O Produtor e o cineasta Zózimo Bulbul – o inventor do Cinema Negro Brasileiro”. Revista Crioula, São Paulo, n. 12, nov. 2012, p. 17.

20. Ibid.

21. Selonk, 2004, p. 98

22. The Rio Cine Festival was launched in 1984. After a fusion with the Mostra Banco Nacional de Cinema, it became, in 1999, the Festival do Rio, as it’s known today.

23. Bulbul, 2007 apud DE; Vianna, 2014

24. Noeldos Santos Carvalho,. “O Produtor e o cineasta Zózimo Bulbul – o inventor do Cinema Negro Brasileiro”. Revista Crioula, São Paulo, n. 12, nov. 2012, p. 19.

25. The Panafrican Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou is the largest African film festival. It’s a biennial event held at Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, where the headquarters are located.

26. Bulbul, 2007 apud, DE; Vianna, 2014

27. Established by the Law nº 11.096, officialized in January 13, 2005, the Programa Universidade Para Todos (PROUNI, University for All) offers scholarships for students who have enrolled in private universities, since in Brazil only the State and Federal universities are tuition-free. The program, which also sponsors students interested in further specialization, is funded through a system of tax-exemption organized by the national government.

REFERENCES

AUGUSTO, Heitor. Past,Present and Future: Cinema, Black Cinema and Short Films. In: Catálogo do 20o FestivalInternacional de Curtas de Belo Horizonte, Belo Horizonte, Fundação Clóvis Salgado, 2018.

CARVALHO, Noel dos Santos. Cinema e representação racial: o cinema negro de Zózimo Bulbul. São Paulo, 2006. Tese (Doutorado) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas.Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2006.

_____. O Produtor e o cineasta Zózimo Bulbul – o inventor do Cinema Negro Brasileiro. Revista Crioula, São Paulo, n. 12, nov. 2012.

DE Jefferson e VIANNA, Biza. Zózimo Bulbul: uma alma carioca. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Afro Carioca de Cinema, 2014.

NASCIMENTO, Beatriz. O conceito de quilombo ea resistência afro-brasileira. In: Nascimento, Elisa Larkin (Org.). Cultura emmovimento: matrizes africanas e ativismo negro no Brasil. São Paulo: Selo Negro,2008. p. 71 -91.

SELONK, Patrícia. Distribuição Cinematográfica no Brasil e suasRepercussões. Pontifícia Universidade do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2004.

VELASCO, Suzana. Sob a luz tropical: racismo e padrões de cor da indústria fotográfica no Brasil. Revista Zum, São Paulo: Instituto xMoreira Salles (IMS), n. 10, 2016. Disponível em:< https://revistazum.com.br/revista-zum-10/racismo-padroes-industria-brasil/> Acesso em 14/03/2020