I – In Good Company

We all know that Carmen was born in Portugal. She came to Brazil as a child at the beginning of the 20th century. A coquettish, pretty girl, a store clerk. It was the roaring twenties, Latin America, Rio de Janeiro, the federal capital of the "United States of Brazil" - the name that, since 1889, was used to baptize the former Empire.

The writer João do Rio, had he known the future, could have interviewed Carmen. He would have said: "Little one, we both suffer from the same curse: we will die early, in the mist of the world". But he was no soothsayer and the colossal headline would never come to be. He died at the age of 39. Carmen, at 40-something. Frozen, lonely, blue on a morgue table.

Well then. Did readers really think that I would start a text about Helena Solberg referring to Carmen Miranda? I am sorry, but it is not so.

It is obvious that Bananas is my business (1995) remains, to date, the greatest success in Solberg's career. An award-winning film, on the threshold between the biography of Carmen and the purging of the director's personal memory.

Because of the film, La Solberg and La Miranda often appear together in the same sentence, closely followed by the ghost of Cinema Novo. Something like Heathcliff, Cathy and the Heights. This was all because, for a while, Helena circulated with the group linked to Glauber Rocha - the pater familias of the movement, the man who carried the tablets of law.

But Brazil is not just about the obvious. I see an aleph, hidden in an old house in rua do Ouvidor, the old center of Rio. It’s there after escaping from the mansion in Buenos Aires, described by Jorge Luís Borges. Through the aleph, the spectator finds a fantastic labyrinth of Marias and Carmens, at different dimensions and times, which intersect and flow through this text.

In the first paragraph, for example, I referred not to Carmen Miranda (born in Portugal, in 1909), but to Carmen Santos (born in Portugal, in 1904). Both had the same official name, given by their parents: Maria do Carmo.

Carmen Santos was an actress, director, producer, and diva of Brazilian cinema. A former seamstress and former saleswoman, like so many immigrants. Like so many "portuguese girls", who climbed the bohemian and stony hillsides of Rio. Carmen Santos (aka Maria do Carmo Santos Gonçalves) worked in the Parc Royal boutique. Carmen Miranda (aka Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha) was an employee at the Radiante boutique - not by chance, the same name as Helena Solberg's company, Radiante Filmes.

You see, reader, if there is a similarity between these two Marias, I now call a third: Adalgisa Nery, aka Adalgisa Maria Feliciana Noel Cancela Ferreira. Born in Rio de Janeiro, in 1905, daughter of a Portuguese mother. Her mother died early, a fact that yielded the painful pages of A Imaginária, a book (unjustly) seldom read.

A woman with the same cry for freedom deep in her heart, Adalgisa was not from show biz like the other girls. She was a writer, a friend of Frida Khalo, and the widow of the painter Ismael Nery. She married Lourival Fontes, an ogre nurtured by the Getúlio Vargas dictatorship. Behold: separated from Lourival, she became a congresswoman, faced Institutional Act 5 - the same AI-5 that intoxicated the characters in Meio-Dia (1969), which we will talk about later. Adalgisa has always stood between intelligence and personal promotion. A sphinx-like creature.

As if the three Marias mentioned so far were not enough, here comes the fourth: Helena Solberg herself. Aka Maria Helena Collet Solberg. She debuted as a director with the short film A Entrevista (1966), followed by the short film Meio-Dia, while still living in Brazil. Soon thereafter, she would move to the United States of America for three decades.

It is, therefore, in the midst of this feminine universe that we understand Helena Solberg and her role in Brazilian cinema. In good company, surrounded by different generations and noises. Someone who is not limited to a single menu - Cinema Novo. Even because cinema is only a piece in the mission she faced: that of breaking her own mirror.

II – Bélle Epoque in the Counterculture?

Carmen Santos, Carmen Miranda, Adalgisa Nery. All three are of the same generation as that of another lady, Celina Solberg, Helena's mother. All of them were born in the first decade of the 1900's, old enough to be daughters of Helena Morley, a pseudonym used by Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant (1880-1970).

This is a great clue for Solberg: her parents' generation. Yes, parents. That traditional and droppable institution questioned by the counterculture of the 1960s, of which A Entrevista and Meio-Dia are classic examples.

From the age of thirteen to fifteen (1893-1895), Alice Brant wrote diaries. Almost fifty years later, they were published under the title Minha Vida de Menina. The text was received as a masterpiece by literary critics. In 1969, director David Neves adapted them for cinema (Memória de Helena). He used urban elements, such as Super-8, cars, asphalt streets, a leading man with long hair.

A century after the creation of the diaries, it was Solberg's turn to write and direct Vida de Menina (2004). Together with Elena Soárez, the co-author, the two captured the atmosphere of the past. They plunged into the period from 1893 to 1895 for a portrait as close as possible to Alice's daily life.

But beyond this: Helena (Solberg), Elena (Soárez) and Helena (Morley) gave themselves over to a lost continent - childhood - to which we always return.

At this point in the text, the aleph determines an expansion of consciousness for the reader. There are dimensions that are strangely similar, despite being far apart in time and space. They defy the laws of nature. They are cosmic dust.

On one side, the 19th century, the countryside. On the other, the 21st century, the movie theater. In between, supernaturally connected, is adolescence. Just as in Meio-Dia - filmed in 1969 - Alice's diaries feature a rebellious girl who challenges authority and hates being coerced by older people.

Of course, there are nuances. Alice Dayrell saw slavery up close - without metaphors, since it was only a short time before the "emancipation" of black people in Brazil (1888). However, the mixture of oppression and delicacy in Vida de Menina also takes us back to Meio-Dia and A Entrevista. Alice did not know how to deal with so much anxiety, so much desire to circumvent and, at the same time, respect religious education. To fulfill the (sacred) duty of an honest woman. The girls in A Entrevista also have doubts between the futile and the complex. How can they be both happy and discreet? Shall they comb their hair, but also think about the meaning of life?

Alice Dayrell was countercultural in her own way. A real-life Josephine March, who didn't consciously realize how literature saved her life. She drew beauty from the microcosm of everyday life: the smell of the cake baked by her grandmother, the figures in the town of Diamantina. No running water, no sewage, but with hormones racing. Only in 1942, at the age of 62, did Dayrell have the courage to publish her writings, which reveals a remnant of guilt for her excesses as a girl. And guilt is the full course of A Entrevista.

III – Inside the Home: A Entrevista

Far from the belle époque of the 19th century, A Entrevista and Meio-Dia represent the turn of the 1960s to the 1970s.

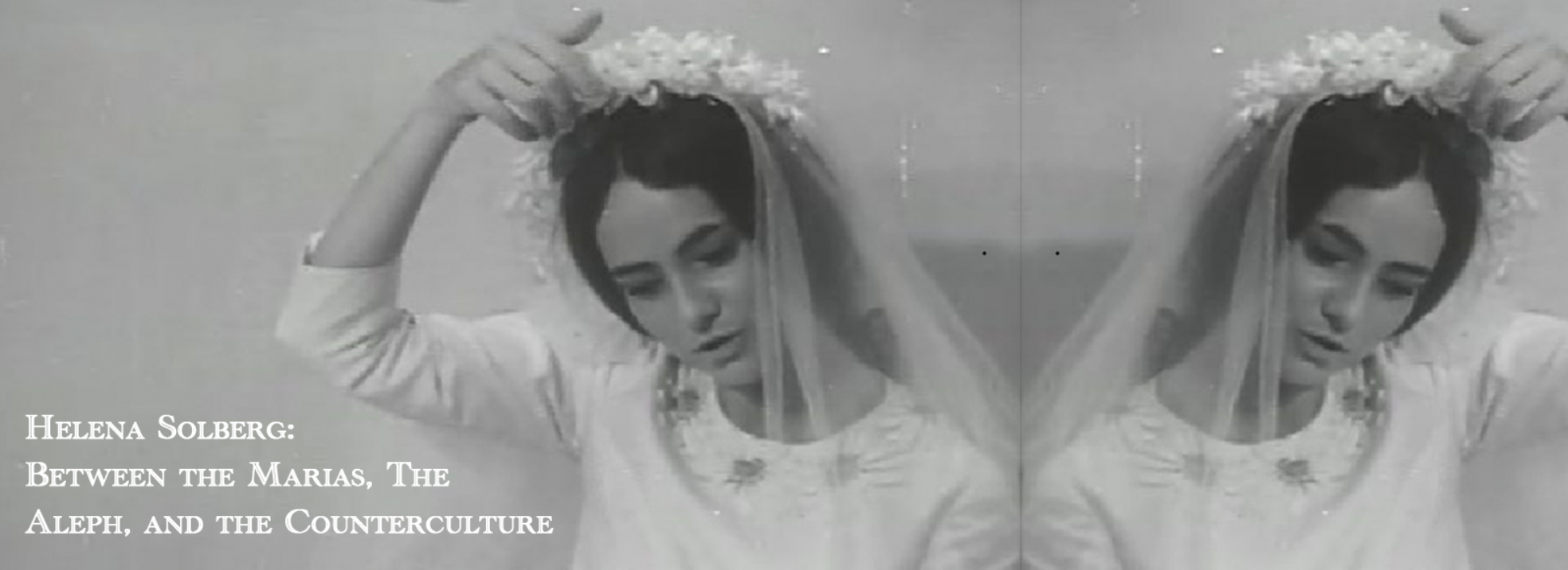

Meio-Dia carries the slogan "it is forbidden to forbid" in the eyes of the children. A Entrevista is a collection of conversations with women, whose voices are heard as one of them prepares, it seems, for a wedding ceremony. Glória Solberg, Helena's sister-in-law, poses as an actress in the neorealist style, with no training for the job.

Gloria walks lightly, and lies on the beach. In a sweet, enchanting eroticism, she rubs sunscreen in the folds of her bikini, and the viewer is left in the tension between rigor (from the statements they hear) and sensuality (from the beautiful scene).

The opening credits mix religious preaching, children's portraits, nursery rhymes, witches, and debutantes. The caption reads: "The testimonies used in the narration were chosen among seventy interviews recorded with girls between the ages of 19 and 27, belonging to the same social group".

Taking advantage of the synchronicities again - I return to the aleph - it is worth pointing out two simple facts. The director of photography, Mário Carneiro, had the same name as Mário Cunha, Carmen Miranda's good-looking boyfriend. Look for photos of the couple and the indelible carnaval behind them. Also pay attention to the editor of A Entrevista: Rogério Sganzerla. The enfant terrible who, in 1968, directed O Bandido da Luz Vermelha, a film that created one of the many splits in Cinema Novo - a movement that was not as solid as they say.

Helena placed Gloria in a wedding dress, with a long white tail. There is a quiet gaze on her face. In one of the most spectacular scenes, the image of a Catholic saint discreetly accompanies her in the corner of the screen. Shortly before, she had opened a closet full of shoes: a clear sign that she was a worldly woman in the eyes of God. Worldly even in the eyes of the critics and the public who would like to see a socio-economic vision of the class struggle.

A Entrevista spends a great deal of time with bourgeois women who, nevertheless, have internal and external barriers between them. We hear statements about marriage, religion, education, control, motherhood, sex, and even a female version of the myth of the toothless vagina - "I hate being dominated by a man," says one of the voices.

There are female interviewees capable of clichés ("a woman is only fulfilled when she gets married") or of defeatism ("I would like to be active, to do things. But I don't really see a path. Maybe a confusion of ideas"). Others, of pure delirium (the woman should be "socially perfect [...] She needs to be cultured, read a lot. Fill her life with classes, lectures, but not devote herself to a job").

The breaking of taboos is translated visually at one moment: Gloria bites her nails, annoyed. She talks about accepting her own ambiguities, about the "incoherence of things". Notice Helena Solberg sitting on the sofa, in a Hitchcockian intervention, gazing at her sister-in-law with nonchalant elegance. Helena placed A Entrevista inside her own house.

Although made three years later, it makes perfect sense to watch Meio-Dia right after A Entrevista. The final scenes of A Entrevista serve as a bridge to Meio-Dia, between shots of the "March with God for Freedom" - a conservative movement that supported the military regime of 1964, father of the AI-5. Rogério Sganzerla, prophet of chaos, assembles the last moments with a confusing mass of images, sounds, and cuts. However, one can hear something that is typical of Solberg's lyricism. One of the interviewees says, in the delicious prosody of the carioca women of the 1960s: "I think politics deteriorates man a little. [...] Kind of animals, you know?" Although it does not deal with political activism - a target of the director in the 1970s - A Entrevista speaks of existential ruptures, doubts and revolutions of manners.

In an exercise of abstraction, Helena's mother, Celina Solberg, could serve as an example for the internal contradictions presented in the film. Celina was born in the seigniorial neighborhood of Botafogo. Far away from rua do Ouvidor and the bohemian glories sung by Carmen Miranda and Carmen Santos. She forbade her daughter to go to Miranda's funeral, whom she didn't like.

Elderly, Celina has made peace with the past. Perhaps she has managed to open her arms to what is different. During the recording of Bananas is my business, she fell in love with Eric Barreto, the actor who served as Carmen Miranda's host. Eric and Miranda formed a single entity. It is possible to feel Celina, Eric, and Miranda inhabiting the invisible, the glorious beyond. I imagine them talking about a new chapter for Religiões do Rio, João do Rio's classic work. Preferably about Umbanda. João watching everything, with a slight torpor and sincere interest.

IV – Beyond the Mirror

In A Entrevista, Helena talked to women of her same age group and social background. The result sounds à la clef, like someone standing in front of a mirror and deciding to break it. '

After all, in 1966, Helena was also married with children. She was fulfilling the social duty imposed on every human being born with a vulva. She signed the short film as Helena Solberg Ladd - then wife of James Ladd. In the future, she would leave her last name dormant, preferring her paternal Solberg. She attended the Catholic Pontifical University. She studied with men, something unheard of for someone raised in a nun's school.

It had only been four years since both the interviewer and the interviewees had received small handouts from Brazilian legislation. In 1962 the Married Women's Statute (Law No. 4.121/62) was published. The utmost boldness was allowed. Women were allowed to conclude business deals without their husbands' endorsement. To exercise their professions and make use of their work output. They were allowed to keep custody of their children in case of separation - but remarry only after 1977, with the Divorce Law.

This background is not always mentioned when discussing the film, but it is directly linked to the asphyxia that prevails in the air. And that reigned for eons in Brazilian society.

Adalgisa Nery was one of the girls who used her marital status to escape from her original family. She betrayed, was betrayed, loved, unloved. Little did she know that her first husband's home, surrounded by religious madwomen, was more hallucinatory than the previous one.

As the aleph orders, this unsuspecting woman was also responsible for the preservation of Parque Lage, in 1960. Lota de Macedo (aka Maria Carlota Costallat de Macedo Soares), architect and former companion of the poet Elizabeth Bishop, considered it a twin of the Bois de Bologne. At Parque Lage, as a child, Arduíno Colassanti - the long-haired leading man in Memória de Helena - lived there. (The dimensions of space and time always intersect).

For it was Lourival Fontes' ex-wife who had a firm hand, eagle eyes, and collaborated to maintain the park. Without her, the place would probably have become a myriad of gray buildings. Solberg's colleagues could thank her: Joaquim Pedro de Andrade shot Macunaíma at Parque Lage in 1969. Glauber Rocha, Terra em Transe, in 1967.

It is also near Parque Lage, in Jardim Botânico, that the character Ana, in the short story "Love", by Clarice Lispector, has a vertigo and sudden uneasiness. A lonely housewife, on the verge of exploding. One more suffocated in the world. It would fit like a glove in A Entrevista.

In the prehistory of the sexual revolution, existing was not easy. Just remember the girl who, abandoned by the father of her son, runs with the boy in her arms until, exhausted, before closing her eyes to death, she sees the child being devoured by a wild animal - "Os porcos" (1903), a short story by Júlia Lopes de Almeida. Just leave even 1903 and reach the 21st century in Solberg's documentary Meu Corpo, Minha Vida (2017). The brutality is the same.

Hence the revolutionary character of the financial independence of women like Carmen Miranda and Carmen Santos. Miranda's millionaire balangandans and Santos' Brasil Vox Filmes. In this broth of backwardness and Brazilian epiphanies, it is easy for the spectator to become depressed by some of the women in A Entrevista. What they could have been and were not.

V – Meio-Dia and the World Outside

Solberg went beyond. Already without Ladd, she wrote Meio-Dia. The film continued to deal with prohibitions, this time with children. If A Entrevista touched the taboo of the virginal woman, Meio-Dia touched the taboo of child naivety.

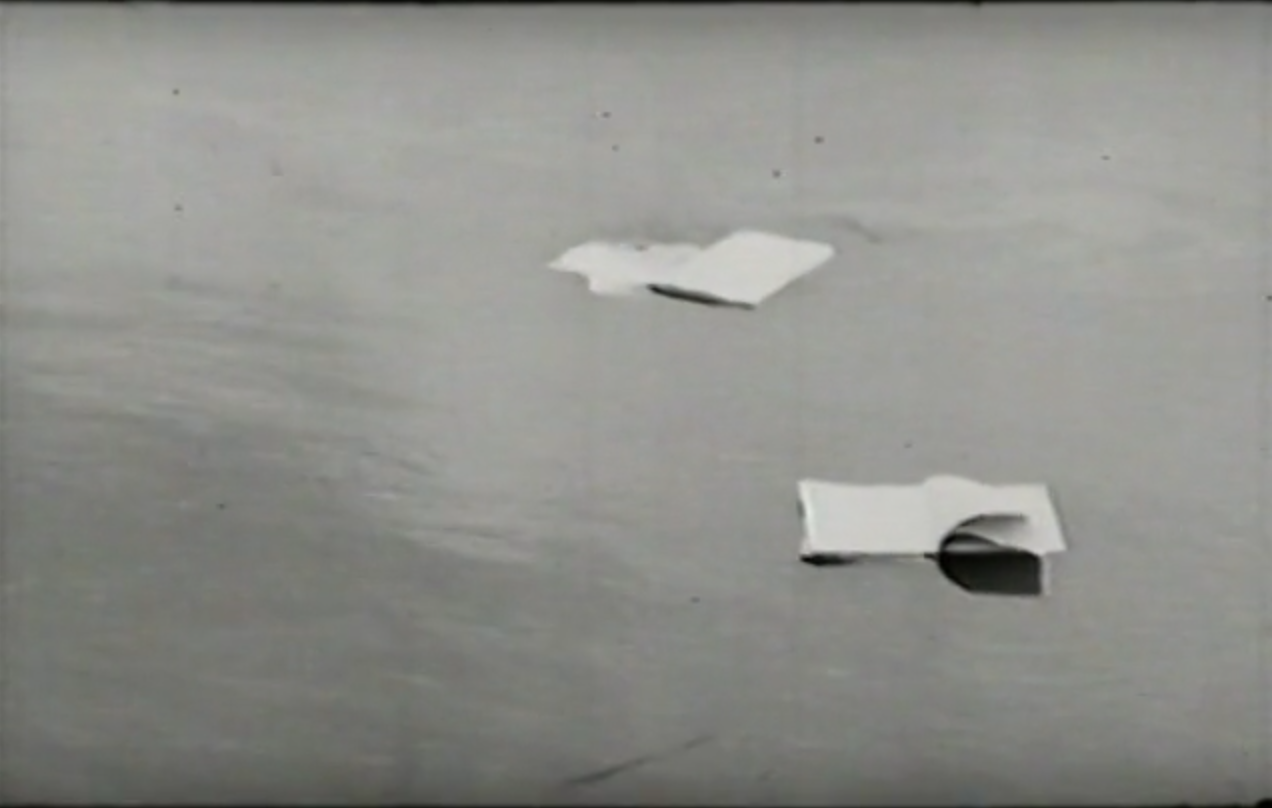

In an emblematic scene, actor João Farkas raises his bangs and throws the schoolbook into the middle of a river. One might remember the canoe in A Margem (1968), by Ozualdo Candeias. In the film, a select (and dreamlike) club of passengers sails down a river, as if to represent those on the margins of society - hence, for many, the nickname cinema marginal.

It turned out that, amazingly enough, the students of Meio-Dia were also on the sidelines, squeezed between obedience and anger. Ready to use the techniques of preadolescence.

They were evil: they assaulted a teacher. They were suckers: scorned at a soccer game. They were confused: they had homes and livelihoods; others did not.

And if none of it is real, the reader should not despair. Many times, the short film seems like a hallucination. Few dialogues, many external scenes, the graffiti "the dictatorship is fucked up" on the school's wall. The film brings a direct reference to the Parisian slogan "prohibition is forbidden", the same one that Caetano Veloso borrowed in the homonymous song, heard during the short film. In this continuum of sixty-odd ideas, everything conspires like the director's howl, but placed in the soft mouths of little angels, between truth and illusion.

The promise of suicide of one of the boys - he puts a plastic bag around his head - is the external expression of what was happening inside himself. The right to cut class - a human and fundamental right - is exercised without linearity, without a beginning-middle-and-end. The scenes overlap, at high speed. Marcelo Zona Sul (1970), by Xavier de Oliveira, would treat in a Zen-like way the Maoist questioning in Meio-Dia.

Mauro Alice, the late, legendary editor, once told me that as a little boy he saw Mädchen in Uniform (1931, Leontine Sagan) in the cinema. What enchanted Mauro - interestingly Alice, like Dayrell - was the children's sense of belonging. The charitable hand of the teacher, who felt penalized by them. Meio-Dia has an oppressive atmosphere and the unity of the children. However, nothing of the charitable hand of the adults. If there was, the hand would probably be severed.

Helena Solberg usually approximates Meio-Dia with Jean Vigo's Zero Conduct (1933) and Truffaut's The Misunderstood (1959). This approximation sounds quite important. For most of his Cinema Novo colleagues, Truffaut was considered alienated, petit bourgeois, and mediocre. They preferred Jean-Luc Godard or Roberto Rossellini. To create a chronicle of the middle class, like Solberg's, seemed like a waste of time.

Not by chance, Antônio Calmon - Glauber Rocha's assistant in Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964) - left the group and went to read the literature of Yukio Mishima. He was looking for a profane work, far from the aesthetics of hunger and the backlands of Euclydes da Cunha. The cracks in Cinema Novo became larger and larger. In Boca do Lixo, in the underground of São Paulo, other idols appeared.

We should not blame the groups themselves or even the excess of testosterone. It is necessary to put the magnifying glass on the historical moment, on what was deep and psychotic in the country and that flowed into the cinema. Otherwise, we would be engaging in a witch hunt exercise. Several topics were left out of the so-called "intellectual" and "serious" cinema. Besides Calmon, José Silvério Trevisan lived hippism in his own way. Walter Hugo Khouri was an existentialist in the middle of a crossfire, at the margin of state incentive. Other examples continue, down the road.

As for the rare female participation behind the camera, you can count on your fingers the women who, up to the 1960s, had directed, produced, scripted, or approached films. And this over a considerable lapse of time.

I mention two more women from Solberg's parents' generation, born in 1904. Cléo de Verberena, aka Jacyra Martins da Silveira, director of The Mystery of the Black Domino (1931), and Gilda Abreu, director of O Ébrio (1946) - a blockbuster starring her husband, singer Vicente Celestino -, actress and director in Coração Materno (1950) - also with Celestino.

The reporter Dulce Damasceno de Brito walked the fine line between a Hedda Hopper and an industry trailblazer. In her book Lembranças de Hollywood she provided the testimony of someone who worked in the press for a long time. Also deceased, Maria Beatriz Roquette-Pinto Bojunga - daughter of Edgard Roquette-Pinto, master of broadcasting in the country - worked at INCE (National Institute of Educational Cinema), circulating among names such as Humberto Mauro. In the middle of 2021, researcher Alice Gonzaga is discussing national cinema and, as a bonus, maintaining the legacy of her father, Adhemar Gonzaga, founder of Cinédia studios.

For Solberg's contemporaries, figures like Carmem Santos sounded like Roman vestals, vanished on the Palatine Hill. In 1967, filmmaker Ana Carolina was studying at the Cinema School of the São Luís College. She started out in documentaries and later delved into the exact opposite, with surrealist films.

All in all, the cinema created by women in Brazil is a fusion of styles, of social cuts, of political follies. However, the alert persists. They were and are anointed in the spirit of freedom.

Helena Solberg did not see the clash of currents that bled the Brazilian avant-garde in the 1970s up close. In 1971, she went with her family to the United States, when another phase in her work began - linked to the feminist movement, and later to Latin American politics. The time in the US grew. Grew, and so many moons passed. When she returned to Brazil, she arrived in the videocassette era, one step away from the Internet. Then she began producing, writing, and directing the phenomenon Bananas is my business. From the 1990s to the 2020s, she returned to documentary and fiction, with no defined order, interspersing projects. Helena opens whatever imaginary door she prefers and focuses on the present, the past, or the future. As a documentarian or fictionist, Helena Solberg remains in action.