The genesis of the modern Brazilian police film can be associated with two filmmakers named Roberto: Pires the Bahian, who directed Redenção (1959), Tocaia no Asfalto (1962) and Crime no Sacopã (1963), and the carioca Farias, director of Cidade Ameaçada (1960) and Assalto ao Trem Pagador (1962). Both worked on the margins of Cinema Novo and were cinephile filmmakers with a taste for American commercial cinema and a dedication to careful craftsmanship, finding dramaturgical possibilities to imagine resistance and revolt in acts of crime. With the exception of Redencão (a crime and punishment thriller), all of these films were more or less directly taken from the Brazilian police chronicles of the 60s. In these films, famous crimes and criminals were reimagined for their possible approximations to already established cinematic imagery and for their political force. Brazilian crime cinema in the 60s, as a genre, occupies the space between police chronicles and proud cinephilia, between respect for the facts and filmic conventions.

Brazilian crime cinema of this era is haunted by the social bandit, a figure that allowed filmmakers to ensure that their film would have greater meaning beyond an incursion into the criminal world. This type of character, so central to leftist Latin American fiction of the 20th century, gained strength in Brazilian cinema, both in the films of the cangaço cycle and in the crime films of the period. The same criminals who once spread dread in society were resignified by politically engaged artists as figures of resistance, whose illegal acts were meant to oppose the social status quo (even if those characters only occasionally showed self-awareness about it). The two classics by Roberto Farias are direct about their desire to redeem two frightening figures of the Rio police chronicle, Promessinha and Tião Medonho, by portraying them as political actors. Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s 1962 adaptation of Nelson Rodrigues's Boca de Ouro dealt directly with the press sensationalizing the exploits and dangers of famous criminals and the dramaturge's desire to explore the lives of the criminals beyond this. This idea would be turned into radical pastiche years later by Rogério Sganzerla in O Bandido da Luz Vermelha (1968). Sganzerla was aware of the procedures innate to the sensationalist press, but also those of the cinema, ready to reaffirm the anarchist potential of the title character's crime wave while looking with a certain suspicion at the sentimentality behind the concerns of Farias. During his time as a critic at the beginning of the decade, Sganzerla did not hide his passion for Francesco Rosi's Salvatore Giuliano (1962), perhaps the purest example of social banditry in cinema of that time. In Bandido, the cineaste doesn’t use the mixture of empathy and political significance to rethink, in accessible terms, the violent acts of his character. On the contrary, Sganzerla wishes to reinforce the blunt nature of said acts; if the red light bandit is a relevant political figure, it is precisely because he is dangerous, violent, and a real threat to Brazilian society of that time.

One last useful observation on this genre of Brazilian cinema is its name. While the English-speaking cinephile always referred to these films as "crime films", in Portuguese, they follow the opposite direction and are called "police films" (“filmes policiais”). Even gangster movies like Scarface (Hawks, 1932) or Bonnie & Clyde (Penn, 1967), in which the forces of law and order practically do not exist, are referred to as policiais. This is peculiar because Brazilian cinema has few true filmes policiais; it was not a genre prodigious in producing either Maigrets or Dirty Harrys. In Brazilian films, the police are almost always ineffective when not corrupt. There are, however, a few films about police procedure which reinforce individual efforts within a suspect system. The realization of such films depends little on the ideological positions of the filmmakers involved, considering that works which could be interpreted as critical of the police system have been made by conservative figures just as much as they have by leftist filmmakers. The name filmes policiais, which of course was not coined with Brazilian films in mind, suggests a communal desire for social order, a desire which Brazilian productions do not share with their Northern counterparts. Instead, Brazilian crime films are more comfortable in the marginality of the underworld, where the figures of law tend towards mischief and criminality. Even José Padilha's two Elite Squad films, whose huge success is tied to how they reinforce a Brazilian middle-class desire to have zero tolerance for crime and urban violence, end up reinforcing the myriad ways in which the police are corrupt.

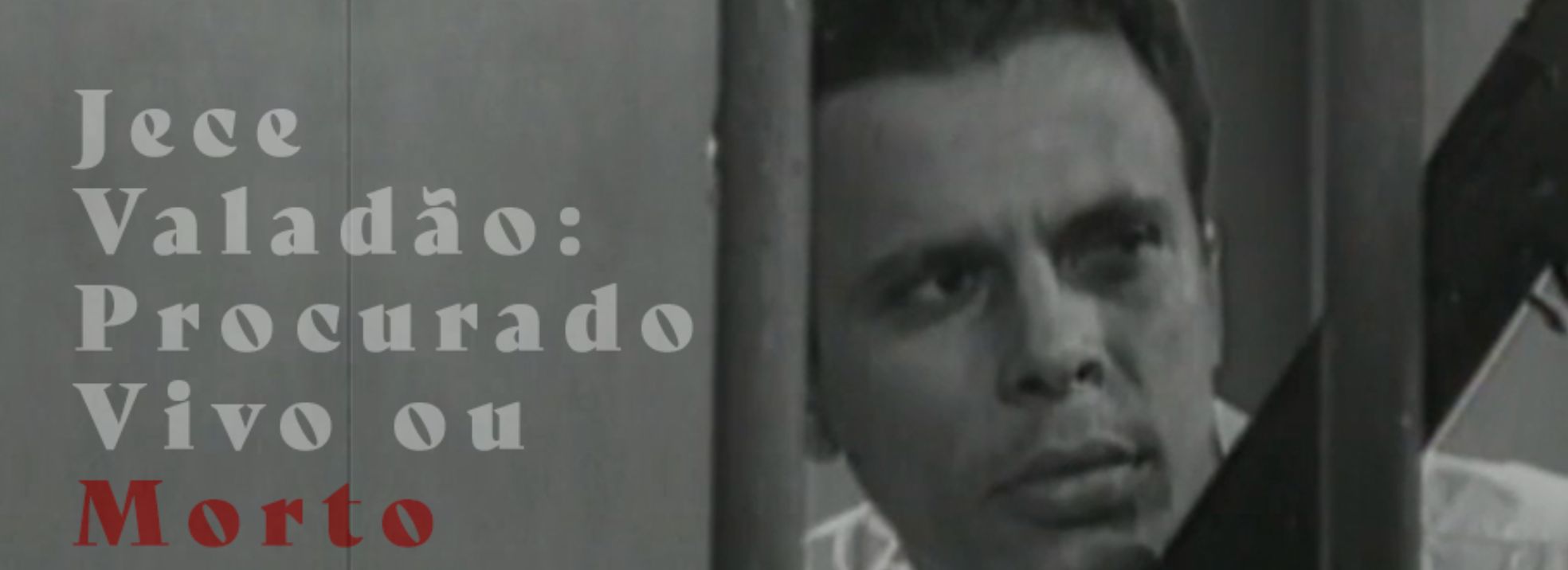

These contradictions are central to the appeal of Jece Valadão, producer and star of Paraíba, Vida e Morte de um Bandido (Lima, 1966). Valadão was the main cinematic crime figure in Brazil during the 60s and 70s, when he was one of the biggest popular stars of Brazilian cinema (and one of the few stars associated more with cinema than TV). Valadão is a fascinating figure with an electrifying stage presence, holding a prolific body of work as a producer, and having directed a series of films in an irregular but very personal way. Valadão began his career with Nelson Pereira dos Santos in the fifties as an actor and assistant director for Rio, 40 Graus (1955) and worked again for the director as an actor in Rio Zona Norte (1957). In 1962, when he was well established, he would hire Nelson to direct Boca de Ouro (1963). Around the same time, Valadão produced and starred in Ruy Guerra's Os Cafajestes (1962), one of the first films associated with the Cinema Novo movement (the actor would also be a part of one of the last breaths of the movement, playing one of the Christ figures in Glauber Rocha's 1980 film, A Idade da Terra). Despite this, Valadão went against the auteur cinema of that time, becoming not only a man of the film industry, but also one who directly associated himself with the conservative forces of the period. Valadão's image is one of the first that comes to mind when one thinks of conservatism during the years of the military dictatorship.

A film that says a lot about the figure of Valadão was Eu Matei Lúcio Flávio (Calmon, 1979). When Hector Babenco had his first big success with Lúcio Flávio, o Passageiro da Agonia (1978), the film biography of a criminal who became famous because he openly defied the pro-government death squad, Valadão decided to film a response, producing and starring the next year in Eu Matei Lúcio Flávio. Said response is a film biography of Mariel Mariscöt, the corrupt policeman whose image became mixed with that of the death squad. Valadão not only produced and starred in the film, but also stated that he knew the real Mariscöt, who at that time had gone from celebrity policeman to major embarrassment of conservative circles for his involvement with the criminal world and subsequent incarceration. The film, very well directed by Antonio Calmon (who began his career as an assistant to Glauber Rocha), is a shameless cash grab that leeches off the work of respectable progressive filmmakers and makes a direct defense for its main character. Calmon’s Mariscöt is an abject, but still praiseworthy figure in the film, embodied by Valadão as if inspector Harry Callahan allowed himself to be drawn into the same world of crime he works in, while retaining a moral superiority. Eu Matei Lúcio Flávio is an extremely reactionary film, which, in 2021 seems more politically useful than Babenco's well-intentioned film. Eu Matei Lúcio Flávio is one of the most honest radiographies of the type of social drives that have produced grotesque figures such as Mariscöt or Jair Bolsonaro.

From the beginning of his career, Valadão embodied the title of Ruy Guerra's debut feature, playing cafajestes (scoundrels) who often followed this same path of a reproachable, but highly charismatic marginalized figure. If there is a strain of sentimentality in his films, it takes form as a nostalgia for the marginal bohemia of a Rio de Janeiro undergoing the process of erosion. In the films that Valadão made as writer/producer/star/director, there is a deep empathy for this underworld, as well as a constant accusation for the supposed superiority of his audiences over it. His vision of this world is most directly exposed in the title of one of the films he directed in 1975: Nós, os canalhas (We, the Scoundrels).

From early on, Valadão realized that controlling his own image was important, and with few exceptions (such as Anselmo Duarte's 1969 western Quelé do Pajeú) he produced the films he initially acted in. Valadão’s first partnership began with Herbert Richers (who was also responsible for the aforementioned Farias policiais and much of Rio's commercial cinema of the 50s and 60s), after which he went on to create his own production company, Magnus Filmes. One among Valadão's many contradictions is that despite his association with much of the Brazilian exploitation cinema, he often produced films by ambitious and experimental filmmakers, such as Braz Chediak's two adaptations of Plínio Marcos plays, Navalha na Carne (1969) and Dois Perdidos Numa Noite Suja (1971) (in the former title he also memorably plays the role of Vado, the pimp), A Deusa Negra (1978), directed by the Nigerian Ola Balogun in Brazil, and Julio Bressane's O Gigante da América (1980). In his vehicles, Valadão usually shifted between his self-direction with an unmistakable heavy hand and passing the films over to experienced Brazilian industry directors like Antonio Calmon and Alberto Pieralisi.

It is in this context that in the late 1960s, Valadão starred in and produced two gangster films, Paraíba, Vida e Morte de um Bandido (Lima, 1966) and Mineirinho, Vivo ou Morto (Teixeira, 1967). In a way, these films are linked both through through their titles (in English: Paraíba, Life and Death of a Bandit and Mineirinho, Alive or Dead) and the criminals they portray. Both main characters were taken straight from the Rio police chronicles with nicknames that reinforce their position as outsiders (it is useful to point out that "paraíba" is a derogatory term that southeastern Brazilians use for migrants from the Northeast region and its use in the title adds another dimension to how the character is seen). Both films adapt their real stories into fairly recognizable dramaturgical arcs and do little to hide their desire to function as "Brazilian-style gangster films." They are films of damnation, where there is never any doubt that the main character is doomed from the very first shot, their martyrdoms blending into the narcissism of the star. There are some notable differences between the two works, especially the organization of flashbacks in Paraíba and the role of the sensationalist press that condemns the character of Mineirinho to the world of crime.

To make Paraíba, Valadão surrounded himself with a series of figures that, like him, started out in the carioca musical comedies of the 40s and 50s. The film was written and directed by Victor Lima, who began his career as a scriptwriter at Atlântida (he worked on the scripts of some of the studio's main classics, such as Carnaval Atlântida (Burle, 1952), Nem Sansão Nem Dalila (Manga, 1955), and Matar ou Correr [Manga, 1954]) and directed several chanchadas for Herbert Richers (the best probably being Pé na Tábua, from 1957). The editing was in the hands of Rafael Valverde, who started his career with Moacyr Fenelon after Fenelon had left Atlântida at the end of the 40s, and who would be a recurrent figure in Rio de Janeiro cinema whose resume includes a long partnership with Nelson Pereira dos Santos. Art direction was the responsibility of Cajado Filho, who, since the 1940s, had been alternating as set designer and scriptwriter in various commercial films in Rio de Janeiro and who also had the distinction of being the first black person to direct a feature film in Brazil. No doubt, the crew behind the film was very experienced, but not one that would be commonly associate with a crime film like Paraíba.

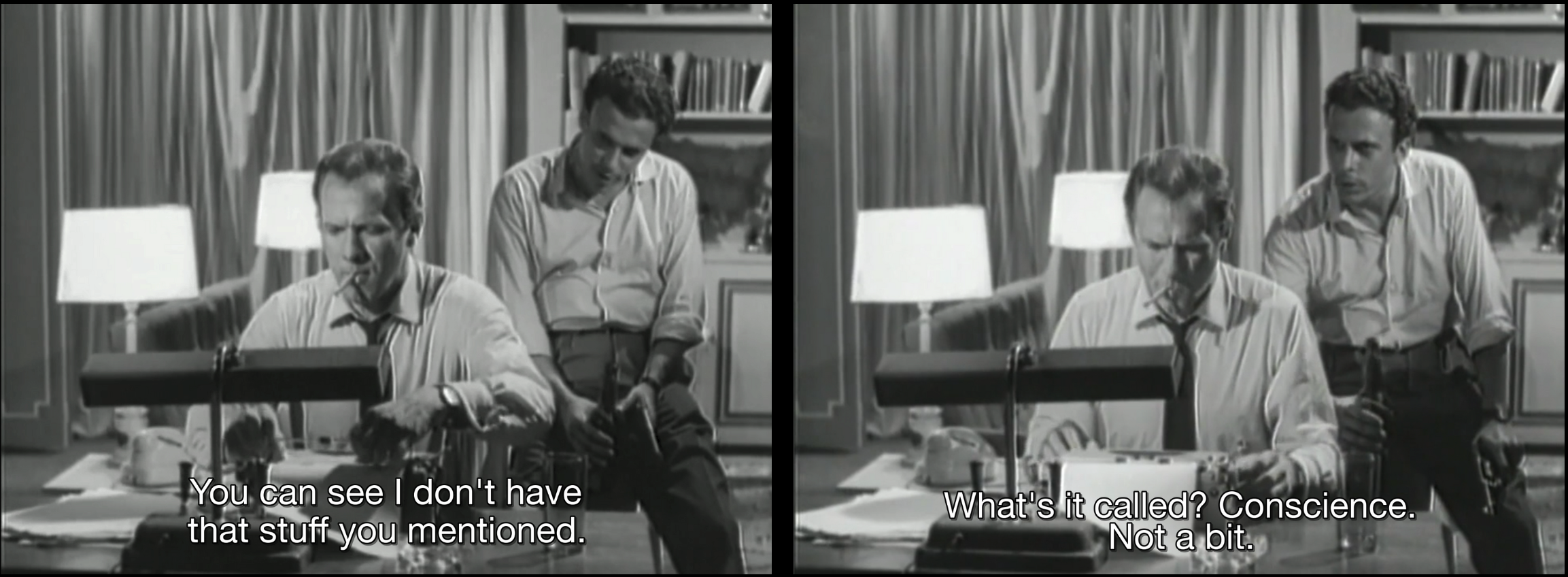

Paraíba, Vida e Morte de um Bandido is an exception in the career of Lima, who was more used to directing comedians such as Ankito, Ronald Golias, and Renato Aragão. His directing style tended to gravitate towards the light tone of the carioca comedy, having very little in common with the formal refinement usually associated with action films. Braz Chediak, who co-wrote Mineirinho and began working with Valadão around this time, described Lima in a 2018 interview: "Victor knew filmmaking like an artisan, he was a good craftsman. But he wanted to make it fast. If he was filming here and the set were a desert, for example, but a car passed in the background, he wouldn't shoot another take. He would say: 'If our audience notices that detail, it means they are not enjoying the film' ".

Consequently, Paraíba is a less dynamic and vigorous film than Mineirinho, less of an action film and possessing a narrative more internalized in its central character. Paraíba’s acts of violence bring a shock and discomfort that is shared between spectator and director. Only Valadão is fully at ease with his character. This creates a curious mismatch between a criminal who is very well resolved with his own monstrosity, but who at the same time always seems out of place on screen. Valadão's narcissism tends to show itself in the sadistic pleasure with which he exerts his power over the other characters, but he doesn’t ask for sympathy from the spectator. His pact with the audience is made more in the sense of sharing his repressed desires. Lima watches Paraíba's trajectory always from a certain distance, less drawn into the Valadão figure than other directors with whom he worked. The temporal back and forth, well-articulated by editor Valverde, reinforces this distance, as the film doesn’t quite follow the classic rise and fall of a gangster arc, but instead flows as a series of violent fragments concerning a bad man marked for death.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, 60's Brazilian cinema was prodigious for its social bandit films. Social bandits are present as Tião Medonho in Assalto ao Trem Pagador (Farias, 1962) and Manoel entering into the world of the cangaço in Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (Rocha, 1964). A film like Porto das Caixas (Saraceni, 1962) reimagines another famous murder from the police chronicles of the time by focusing on the oppressive social forces behind it. Paraíba was released about two years away from Hélio Oiticica presenting at a public exhibition in Rio dubbed Domingo das Bandeiras (Flag Sunday) — an art intervention in General Osório Square where national artists would create flags to then be sold in the streets — a banner of Cara de Cavalo (Horseface), a criminal executed by the police, with the phrase "be marginal*, be a hero*". Crime is a last resource of the oppressed, a tool for reaction. However, Parnaíba operates in the opposite manner. The term criminal is already there in the title without any glamour. When asked about the possible social and psychological forces that drove him to violence, Paraíba is emphatic in his denial. This is a man who commits crimes because he has decided to. He always acts in the heat of the moment.

Paraíba, Vida e Morte de um Bandido is careful to imagine the eponymous character's surroundings, accomplices, lovers, etc. There is room for the inevitable betrayals in accordance with genre tradition, characters rearranged to keep the gears of drama in motion, underworld details that give credibility to the criminal and his gang, but there are no exits; only violent men who dedicate themselves to their own survival. This radical refusal is a very characteristic gesture of Valadão both in terms of politics and drama. Paraíba is a conformist and conservative film in many aspects, much due to the personality of its star-author, and the refusal to socially conscious banditry in the film is a very conscious gesture. As is often the case in Valadão's films, this gesture comes with a genuine enjoyment of the performance of criminality. Any possible political intention behind the refusal of the social reading is frustrated by the actor Valadão, who simply loves all the barbarities his character commits. The flashback sequences in the film could have, in Lima's original script, the intention of denouncing the violence of the criminals, but Valadão's Paraíba is too appealing to allow that. Paraíba may be the confession of a bandit on the verge of death, but it is not a film about how crime doesn't pay. The film may refuse social redemption in its portrayal of criminality, but it is also far from taking the perspective of the police. The point of view that Lima and Valadão suggest is a defense of the value of criminality for its own sake.

In this sense it is fascinating that Paraíba was released about three months after A Grande Cidade (1966), Carlos Diegues's best feature. There, too, we have a migrant who turns into a criminal with great dangerous potential after arriving in Rio. The idea of Paraíba as an outsider in itself brings a great sense of danger to the character (here again, Valadão frustrates the more conservative intentions of Lima's text by only playing himself in Paraíba, this fear of the other becoming blurred between the lines). On the other hand, Leonardo Villar's Jasão in A Grande Cidade is the countryman corrupted by the big city and transformed into a mythical criminal. In both films there is a fatalistic relationship between the city space and death, but in Diegues' film it attains a symbolic quality which explains the tragedy of the migrant character, while in Lima's film it is an element of scenic building that exists not for its social strength, but for its dramatic force.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the constant presence of death in Paraíba. The present tense action of the film takes place inside a Catholic church where the criminal goes to hide after being shot, while the rest of the narrative takes place in flashbacks. From time to time we are brought back to the church as it is surrounded by police. Meanwhile, Paraíba slowly comes to terms with the idea that he has reached his own end. These flashbacks are like the last breath of a condemned man, but it is impressive how the film combines a feverish, tormented tone with an air of resignation that there is nothing left to do but pay for a life of crime. Like a good would-be public enemy, Paraíba has an appointment with a bullet and the gutter. The confession that this film consists of is less a redemption than a definitive entrance into the world of cinema. In Paraíba, Vida e Morte de um Bandido, Valadão, the eternal cafajeste, is having his James Cagney day.