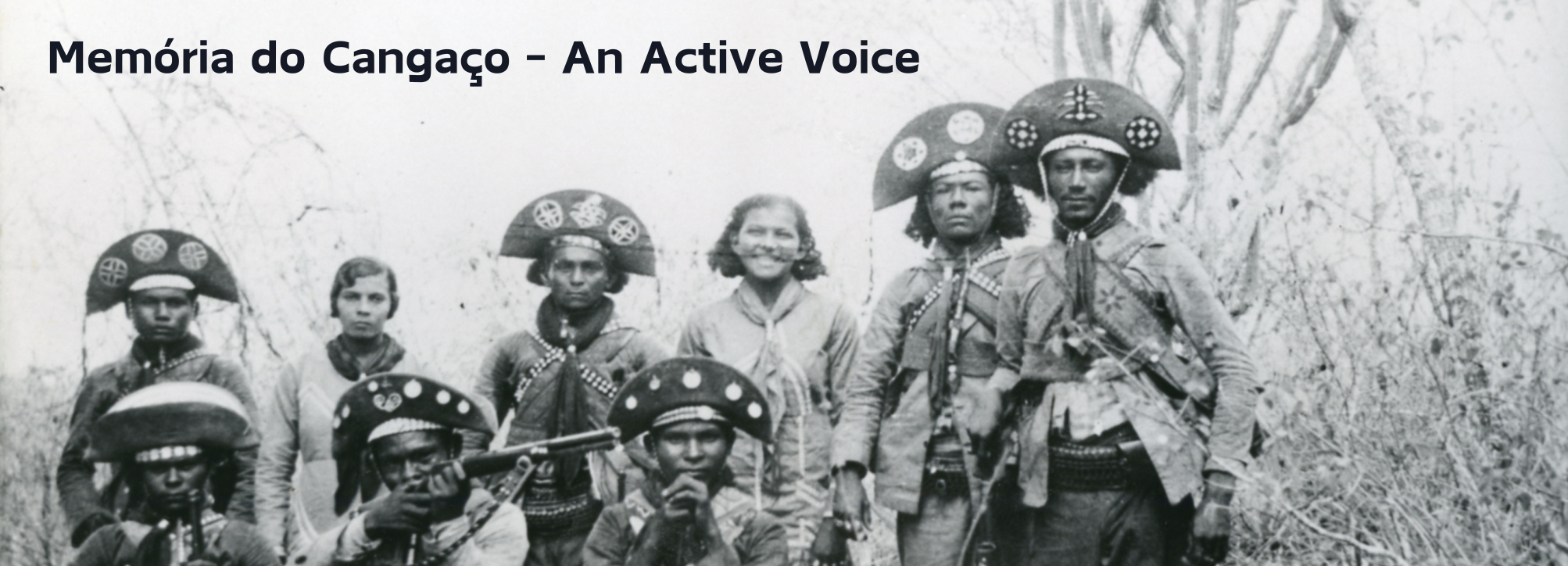

Paulo Gil Soares had just finished working as an assistant director, production designer and dialogue writer in Glauber Rocha’s Black God, White Devil, when he went on to direct his first film: the documentary Memória do Cangaço (Memory of the Cangaço), which would be the first film of the Caravana Farkas. It is not an accident that it took an active stance when confronting its main subject, while avoiding both demonizing and mystifying the cangaço, and distancing itself from the style of sociological documentaries at the time.

It opens in a typically Northeastern setting; from the music of the opening credits to its first images, of a typical market in the Northeast of Brazil. The narrator tells a summarized account of the history of the cangaço, citing some famous cangaceiros and some myths concerning them, such as the idea that “they stole from the rich to give to the poor”. We proceed to the official version of history, via an interview with professor and medical doctor Estácio de Lima. The setting now is the “temple of knowledge” of the Faculty of Medicine of Bahia - complete with Greek columns. Despite the authority and knowledge we were told to expect, the professor’s explanation sounds so absurd it borders on accidental comedy. According to him, the geographical conditions and the “primitive” society alone could not fully explain the origin of the cangaço. The main cause was the activity of certain glands and the body type of the slim sertanejos. If this were a common documentary of that time, the professor would serve as its narrator - the “voice of reason”. But it isn’t. In a clever editing move, his explanation is set to a local man examining the teeth of a horse. A subtle dismissal of the professor’s Lombrosian reasoning.

That’s when our narrator - the filmmaker himself - comes in: “Is professor Estácio de Lima right?” On we go to some socioeconomic data: after an interview with a cowhand who, besides being subjected to injustice and harsh conditions his whole life, was thin (which, according to Lima, would have led him to become a cangaceiro), the narrator lists data to explain that "the sertanejo is a man left to his own devices": facing the absence of justice, illiteracy, low wages... Much more reasonable reasons for the violence in question than the pseudoscientific theory cited by the professor.

There is another moment when the narrator comes in to correct wrong info given by his interviewees. It’s when José Rufino recounts the gunfight when he killed Corisco. For the director, facts come first. But there is room here for inventive filmmaking, especially when folk poetry (cordel) is used in Rufino’s intro and outro, to describe Maria Bonita, and to show that Lampião himself was a poet.

Worthy of note are the testimonies of five characters of the history of cangaço. Besides José Rufino - a famous cangaceiro killer -, there are Benício Alves dos Santos, Ângelo Roque da Costa and Otília Maria de Jesus - all former cangaceiros under the names, respectively, of Saracura, Labareda and Otília. We’re shown a brief attempt of interviewing Sérgia Ribeiro - the former cangaceira Dadá - who shuns the film crew from her home. All former cangaceiros are asked the same questions, especially why they joined the cangaço. Their reasons were, for the men, wanting to avenge and defend the honor of family members, and for the women, being kidnapped by cangaceiros in their teenage years, and threatened with death if they refused to go. On that, Dadá says: “I followed Corisco because I was his wife, I obeyed my husband.” The exception was Maria Bonita, who, we’re shown, left her husband for Lampião. At another moment, Rufino states it was common for police officers to have joined the force merely as a means to avenge relatives who had been killed by cangaceiros.

Another point of interest are the excerpts from the documentary Lampião, o Rei do Cangaço (Alexandre Wulfes and Al Ghiu, 1959),1 the first film to make use of the footage2 shot by Benjamin Abrahão of Lampião’s gang in 1936, which had been confiscated and was unseen since 1937. However, the resulting film failed to understand the phenomenon of the cangaço - which is evidenced by its sensationalist and inaccurate narration.

In Memória, on the other hand, those five eyewitnesses paint an honest and blunt portrait of the brutality of those times, both by the hands of cangaceiros and police officers. Such brutality can be perceived in how Dadá refuses to be interviewed. And Benício admits to the camera that he hates talking about those times. Rivalries, gunfights, severed heads - seven of which were still exposed at the Nina Rodrigues Forensic Institute of Salvador, Bahia, at the time, and which we get to see up close3 - the film doesn’t avoid any subjects.

Other than that, there is a handful of info regarding the clothing, habits, food and organization of cangaceiros and police forces. We see gunshot wounds suffered by people on each side, we hear stories of gunfights, and curious episodes, such as those when Lampião invited Rufino to join his group of cangaceiros. To explain his refusal, Rufino draws a curious parallel between both quarrelling factions: “I didn’t want to join the cangaceiros or the police.” It is as if, to him, the real issue was “carrying a gun, spilling blood”, regardless whether he was on the side of the law or not.

Even though it was not the first documentary about cangaço - there are records of now-lost films made during the years when Lampião’s group was active, such as Lampião: o Banditismo no Nordeste (1927) and the docufiction Lampião, a Fera do Nordeste (1930) -, Memória do Cangaço was probably the first film that took an actively critical stance when looking at that topic. For all that, it is obligatory in cangaço studies, as well as Brazilian cinema.

1. Some sources claim the film came out in 1955 or “in the 1950s”. According to Frederico Pernambucano de Mello in Benjamin Abrahão: entre anjos e cangaceiros (2020), the release year was 1959.

2. Some of Abrahão’s photographs of the cangaceiros had been published as early as 1936, but all the negatives were confiscated in 1937.

3. The heads were taken from the Institute and properly buried on February 6, 1969.