A Social Lyricism

Menino da Calça Branca (Boy in the White Pants), Sérgio Ricardo’s first movie,1 is a 1962 short film made while the Brazilian Cinema Novo movement was still consolidating itself. The film tells the story of a boy from a favela who receives white pants as a gift, and proud of this symbol of social status, wears his white pants while walking through the city of Rio de Janeiro. Sérgio Ricardo’s first film reveals his desire to call attention to Brazil’s lower social classes, something that will become a common theme throughout his filmography (as noted by Gustavo Menezes de Andrade in his 2017 dissertation). Looking at his career as a whole, this wasn't the first time that an interest in exploring the lives of the lower classes manifested itself. For example, besides working as an actor, Sérgio Ricardo began his career as a musician and composer. In his song “Zelão”, made one year prior to Menino da Calça Branca, he sings about a favela musician who lost his home to a flood.

Multi-talented, Sérgio Ricardo both directs Menino da Calça Branca and composes its soundtrack, on which he explores the sonorities of Bossa Nova using only his voice, guitar and flute. In this article, we aim to highlight the major themes of this short film about a favela child in the city of Rio de Janeiro, analyzing the way the plot develops alongside the music in the film, while also taking into account the larger context of music in Brazilian cinema at that time.

Menino da Calça Branca is not the first occasion that a Brazilian film showed images of a favela in Rio de Janeiro. For example, there is the case of a lost 1935 film by Humberto Mauro, Favela dos meus amores. But it was Rio, 40 Graus (Rio 100 Degrees F.) by Nelson Pereira dos Santos which would become an important reference for filmmakers of the 1960s who were looking to film in favelas. This 1955 film portrays the lives of five children from the favela in their daily struggle for survival. Nelson Pereira’s film is considered by many researchers, such as Mariarosaria Fabris (2007), as having been influenced by Italian Neorealism in its compassionately humanist way of looking at the lower classes (holding an “ethical posture”, as Cesare Zavattini recommended). The film is similar to the films of the Neorealists that often have sad endings, where characters have no hope for a better future.2

Rio, 40 Graus contains images made in favelas such as Morro do Cabuçu, and we can even see and hear the samba school Unidos da Cabuçu rehearsing in the favela in the film’s final sequence. It is worth mentioning that Nelson Pereira dos Santos decided to edit Menino da Calça Branca for free because he got excited when he saw Sérgio Ricardo’s initial material. In fact, while Sérgio Ricardo was finishing up edits of Menino da Calça Branca, the Centro Popular de Cultura (CPC)3 put together the collective film project titled (Five Times Favela). This work would be composed of five short films by directors of the emerging Brazilian Cinema Novo movement: Leon Hirzsman’s Pedreira de São Diogo, Cacá Diegues’ Escola de Samba, Alegria de viver, Miguel Borges’ Zé da Cachorra, Marcos Farias’ Um favelado and Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s Couro de gato (Cat Skin).4

Sérgio Ricardo said in an interview that Menino da Calça Branca was considered to be included in Cinco Vezes Favela, but it ended up being denied for its “excessive lyricism”.5 He added in the interview that maybe the film didn't have the didacticism intended by the CPC. It is coincidental that, among the five films chosen for Cinco Vezes Favela, Cat Skin is also a story about favela children. As the themes of Menino da Calça Branca and Cat Skin are similar, this article will compare both films, while taking into account their influential predecessor, Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s Rio, 40 Graus.

To begin, what could this accusation of excessive lyricism be referring to in Ricardo’s film? Like Nelson Pereira and Joaquim Pedro, Sérgio Ricardo filmed on location in a favela (the now extinct Macedo Sobrinho). In the first shot of Menino da Calça Branca we see slum shacks with shabby rooftops, and as the opening titles run, we hear the song “Enquanto a tristeza não vem” (“While the Sadness Doesn't Come”). Then a boy appears (played by Zezinho Gama), playing games such as hopscotch and hide-and-go-seek alone and with his friends. No details of the favela setting are spared, as we can see an open-air sewage ditch that runs through an alley. Menino da Calça Branca does not beautify any aspects of favela life.

Perhaps the most clear example of “lyricism” in Menino da Calça Branca is when Sérgio Ricardo’s favela boy eventually goes to “the asphalt”. “The asphalt” (“o asfalto”) is a term used in popular Portuguese language to connote the city below the hills of the favelas, where the alleys are typically unpaved. Unlike the peanut sellers of Rio, 40 Graus or the boys in Cat Skin,6 when the boy in the white pants leaves the favela, he does not do so to work. Instead, he is allowed a purely playful experience on the asphalt. There, in his white pants, he spiritedly imitates the posture of nearby walking adults, proudly displaying his clean garment while doing so.

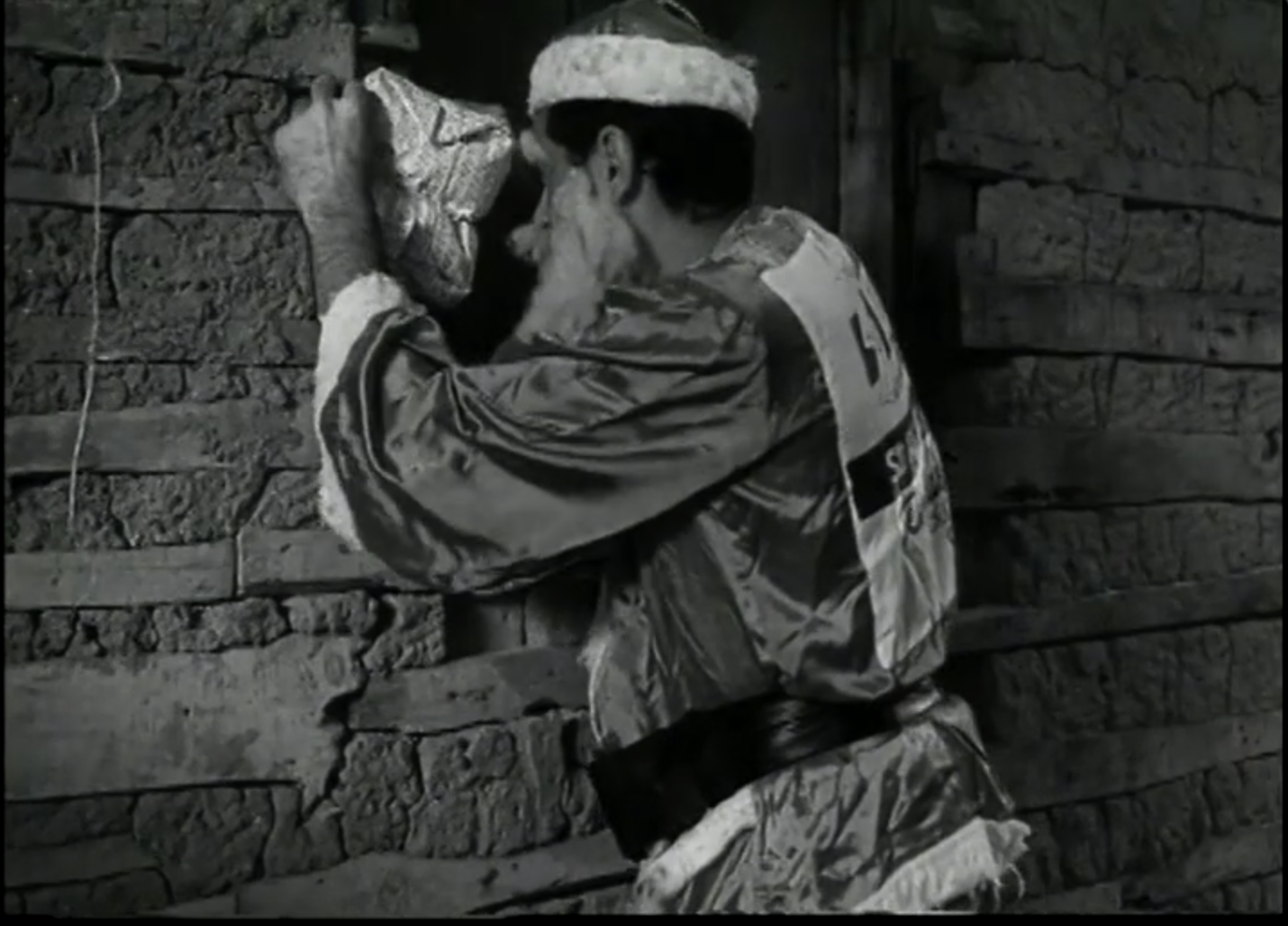

Despite taking the utmost care to keep them clean, the pants of the young boy become completely muddy, causing him to burst into tears. While it is a very sad moment in the film, it is not nearly as inexorable and tragic as the instances of death in Rio, 40 Graus or Cat Skin. In the first example, there is the death of one of the boys; in the second, a beautiful white cat is taken to be sacrificed. The films of Nelson Pereira and Joaquim Pedro display a harshness, a cruelty from which the oppressed cannot escape. This, in a way, echoes some of the destinies of characters from Italian neo-realist films: the unemployed man of Bicycle Thieves (1948) who loses his bicycle and becomes too ashamed to become a thief in front of his son, or the retired man of Umberto D. (1952) who relocates his lost dog, but still has no solution for his own financial survival. In comparison to these examples, Sérgio Ricardo’s boy from Menino da Calça Branca is spared any great tragedy, though tragedy does exist around him. For example, at the end of the film, the boy cries because of his muddy pants and a drunken Santa Claus (played by Sérgio Ricardo himself) tries to cheer him up. The drunken Santa Claus has traits of a tragic character: he also begins to cry and the boy cheers him up in return. Spared of greater tragedy, the boy has his soiled pants washed by his mother and he goes back to playing in the favela in his old shorts.

It is only at the very end of Menino da Calça Branca that an encounter with “the real” (in the sense of Zavatinni’s neo-realism) takes place. We see the boy holding a revolver in a close-up shot, and there is some apprehension as to whether or not the weapon is real and loaded. He shoots and another boy shoots back. The image freezes the dual to a standstill and the film ends.

How should we interpret this ending? Are they simply playing the common game of “Cops and Robbers” with toy guns? Are the guns in their hands real, and a tragedy bound to occur? Or is the film suggesting with this game between the children that they both have future careers in crime? If we interpret the final scene as such, Sérgio Ricardo’s film ends up feeling much more pessimistic than of Rio, 40 Graus and Cat Skin. His lyricism is pregnant with tragedy. The verse of Sérgio Ricardo’s opening and closing title song says it all: “[Happiness] plays a little while sadness doesn't come”.

It should be taken into account that Rio’s favelas were still not so violent during the time of the early 60s when Menino da Calça Branca was made. There was not a large presence of organized crime and drugs, as this is something that only began to occur in the late 1970s. The violence that we do see in Menino da Calça Branca is that of social violence, a violence of being excluded from society. But the end of Menino da Calça Branca, like Paul Klee's Angelus Novus, looks at the future and anticipates, even if unintentionally, the loss of a romantic vision of the slums that will take place, a romantic vision that can still be observed in these films and in their public reception.

One could also argue that there is a “whitening” of the favela in Menino da Calça Branca because its three main characters (the boy, his mother and the doll repairman) are not black. Even though almost all of the boy's friends in the film’s opening shots are black, none play a major role in the movie’s story. Far from being reproaches belonging to our contemporary time in 2020, this same criticism was made at the time of the film by Ruy Guerra and others (Andrade 2017). However, it can be argued that this was a problem of other early Cinema Novo films, as the boy protagonist in Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s Cat Skin is white as well.7

Music and Rios Favelas in the Years 1955 - 1962

It is important for us to consider how the music composed for Menino da Calça Branca can be contextualized within the larger panorama of Brazilian music of the time. This is all the more interesting because Sérgio Ricardo had already established a career as a musician before turning to a parallel career in cinema. Sérgio Ricardo composed the Menino da Calça Branca soundtrack in the Bossa Nova style that he had been previously exploring.8 However, on the soundtrack he solely chose to include his vocals, the guitar, and flute, which was something quite unusual for soundtracks of the time. More generally, one would have appealed toward orchestration, even if the musical piece had originally been a popular song.

For example, this is what occurred in Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s Rio, 40 Graus. Although the film used Zé Keti's samba “A Voz do Morro” (“The Voice of the Favela”) as its main theme, it was orchestrated by Radamés Gnattali, an experienced musician in orchestration who mostly worked in radio, moving between high-art and popular music fields. According to a 2001 interview with Guerrini Júnior (2009), Nelson Pereira would have preferred a less grandiose use of music, but the “orchestra” was almost a natural imposition, as it was then considered to be the standard for “film music”. As such, despite the fact that Rio, 40 Graus had to be interrupted several times due to financial problems, a lot of money was spent in the production to record an orchestral soundtrack.

Building the soundtrack for Menino da Calça Branca was much different than that of Rio, 40 Graus. Menino da Calça Branca was financed by the director himself, and he chose the short film format as it generally allowed for more experimentation. As such, Ricardo employs a much more minimal soundtrack, utilizing only voice, guitar, and flute. The role of music remains primordial in the film, its presence felt throughout nearly its entire length.

In Menino da Calça Branca, music is mostly found in the nondiegetic foreground, and speech is reduced to a minimum. In fact, the only time articulate speech occurs in the film is during the previously mentioned scene when drunken Santa Claus and the boy confide in each other. Even so, the speech is that of a drunken character, and therefore it is hard to make out what is being said.

The film soundtrack is basically built around two songs, “Enquanto a tristeza não vem” (“While the Sadness Doesn't Come”) and “Menino da calça branca” (“Boy in the White Pants”). “Enquanto a tristeza não vem” can be heard during the film’s opening titles, sung with guitar accompaniment by Sérgio Ricardo, with some additional flute. It then returns in several different arrangements throughout the film. For example, when the song is first used, there is a confluence between the diegetic and nondiegetic spaces of the film: the character played by Sérgio Ricardo whistles the main tune of the song and, shortly afterward, a humming with guitar and flute follows the melodic line on the soundtrack. This variation of the song is also heard when the drunken Santa Claus leaves the white pants as a present for the boy when visiting his home in the middle of the night.

When the boy opens the package and sees the white pants the next morning, we hear another piece of music, “Menino da calça branca”. This music continues over wide shots of Rio de Janeiro´s landscape and favelas. The song lyrics directly connect with the events of the film. In fact, the lyrics of the two songs serve a narrative function9 as the film has no dialogue.

“Menino da calça branca” can be subsequently heard on the soundtrack in varying arrangements. During these later moments, the melody is hummed,10 the song transforming into one without words. It is as if the impact of the earlier sung lyrics have resonated into feelings we can now evoke by only hearing the melody.

The great turning point in the film’s narrative is also announced by the soundtrack: the boy, out on “the asphalt”, sees a marching band playing with their brass and percussive instruments to an newly arranged version of the first song of the film, “Enquanto a tristeza não vem”. The music here functions as an announcement that the boy’s perfect experience with his white pants will soon come to an end. Shortly after we hear the music, a soccer ball falls in a mud puddle right before him and the mud splashes all over his pants. The brass band music, whose sound had been suddenly silenced (a common Brechtian distancing effect), suddenly returns to mark the eruption of sadness in the boy.

The song “Menino da calça branca” (accompanied by guitar and flute in a minor tone) is hummed again when the boy, angered at the fate of his soiled white pants, rips out an advertisement for the white pants11 from the newspaper, urinates on the newspaper, and throws the now separated advertisement into the wind. The song “Enquanto a tristeza não vem” is then sung by Sérgio Ricardo to close the film. Taking the lyrics into account, it is possible that the song is being used to emphasize the fact that the boy’s happiness and playfulness is just an interlude for the sadness that is to come.It is also important to highlight, in addition to the general importance of the two previously discussed songs, the great role of the guitar throughout the film soundtrack. Several transition moments that would be conventionally played by an orchestra are made with a percussive pattern on the guitar in Menino da Calça Branca. This reinforces the role of the instrument within the film music, something completely innovative for a score of this period.

Highlighting further comparisons between the music of Menino da Calça Branca and Rio, 40 Graus, it is interesting that both soundtracks are completely based off of one or two songs.12 In the case of Sergio Ricardo’s film, one of the songs is of course “Menino da Calça Branca” and in Nelson Pereira’s film, the previously mentioned samba by Zé Keti, “A Voz do Morro”. In Rio, 40 Graus, “A Voz do Morro” can be heard in the opening titles and functions as the leitmotif of the five favela boys in the film, as well of the favela itself. In almost all of the instances throughout Rio, 40 Graus wherein which “A Voz do Morro” can be heard, Zé Keti’s samba is played in Radamés Gnatalli’s orchestral variation: without lyrics and as nondiegetic music. However, the last time we hear the song in the film, it becomes part of its diegesis, as the music is played and danced to by members of the favela Samba School. It is as if by the films end the samba has returned to its place of origin.

Although Zé Keti’s samba is almost always transfigured into its symphonic format, it is interesting that the film manages to retain its association with the samba musical genre, an association confirmed in its final dance and music sequence. In contrast to this, in the favela shots of Sérgio Ricardo’s film, a samba is twice sung acapella by a (very low) female voice, and the rest of the music is that of Bossa Nova, a genre that was mostly associated with an intellectual urban middle class and which primarily dealt with bourgeois problems. While Bossa Nova typically catered itself to bourgeois life, Sérgio Ricardo was part of a sector of Bossa Nova musicians that aimed to politicize the genre, and his lyrics contain the very social problems displayed within the film, problems the artist was already discussing in his song “Zelão”. As for Nelson Pereira dos Santos, his creative partnership with the samba musician Zé Keti continued into Rio Zona Norte (1957), a film about the “theft” of sambas from their original popular composers by sectors of the middle class.13

The problems of musical authenticity in these favela movies are quite complex, even more so if we take into account that most of the musical incursions we have mentioned, such as those in Menino da Calça Branca, are nondiegetic. To problematize the matter further, we could evoke a very influential film of that period, Marcel Camus’s Orfeu negro (Black Orpheus). This 1959 French production was made with an all-black cast, with children as it’s leading characters, and it was shot in a Rio de Janeiro favela. Its musical soundtrack, performed at times diegetically by the main character Orfeu, was based on the 1954 theater play by Vinícius de Moraes, Orfeu da Conceição. In the film, the music was transcribed in arrangements which were closer to the Bossa Nova genre. In a way, this film influenced an entire tradition of utilizing Bossa Nova music within films which were shot in Rio de Janeiro favelas.

In the case of Cat Skin, the music does not stand out as much as it does in Menino da Calça Branca. The music of Cat Skin remains more subtle despite the fact that, similar to Menino da Calça Branca, Cat Skin is a film that predominantly utilizes music rather than the spoken word. However, voice over is featured very early in Cat Skin, and articulated speech can be found in the diegesis at a latter moment, but only as simple words. Cat Skin also bases its soundtrack off Bossa Nova songs, composer Carlos Lyra playing with the accepted conventions of film music by exploring melodic, harmonic and mainly timbristic variations for the musical incursions of the film. Carlos Lyra and his musical partners Nelson de Lins e Barros and Geraldo Vandré were also a part of the Bossa Nova movement alongside Sérgio Ricardo.

The only song heard with lyrics in Cat Skin is “Quem quiser encontrar o amor” (“Who Wants to Find Love”). The song is played during the scene when we can see part of the famous samba school parade in Rio’s Carnival, and it is as if the song were being sung by the parade members themselves. Even so, there is a basic orchestration to the song as it is not played solely with percussive instruments like what typically occurs during the samba parades. This is also the song that marks the central relationship of the protagonist boy Paulinho with the white cat he steels from the backyard of a rich woman. During the first encounter between this rich woman and the boy at an early part of the film, the rich woman, interested in the boy, calls him over to drink juice prepared by her butler. While this encounter between the woman and boy is taking place, the song “Quem quiser encontrar o amor” is played non-diegetically in an instrumental jazz variation. This is interesting because it had become accepted, at least in Brazilian cinema circles of that time, that jazz music was mainly associated with the bourgeoisie. The same music, orchestrated differently with more stringed instruments, is what we hear in the film’s moving scenes of the boy becoming close to his white cat, struggling with the difficult decision to sell him for pocket change.

The opening and closing song of Cat Skin is “Depois do Carnaval” (“After Carnival”) by Carlos Lyra and Nelson Lins e Barros. In the film’s opening shots, we can see a view of the city of Rio de Janeiro from the favela which reminds us of the opening shots of Rio, 40 Graus. However, in the beginning of Cat Skin, besides the traditional orchestration, the percussive instruments that can be heard during the music of the opening titles linger after the titles are concluded, becoming diegetically represented by shaking tambourines. Thus, we can detect a stronger relationship on display here with the samba of the favelas. It is also interesting that, if some transitions in Menino da Calça Branca were punctuated by Sérgio Ricardo’s percussive guitar pattern, in Cat Skin, percussive instruments both underscore the boy’s “cat hunt”, and later their own persecution by the people from “the asphalt”.

Final Considerations

It is thought provoking that both Menino da Calça Branca and Cat Skin do not have the traditional "from the roots" samba at the base of their soundtracks. But the Bossa Nova in both films was perhaps easier for a foreign audience who would have already been familiar with Marcel Camus’s Black Orpheus. Regardless, this type of music has remained a symbol of Brazilian favelas, and by extension, of Brazilian music. However, even Zé Keti’s samba in Rio, 40 Graus is in orchestral form, it is also so distant from “the roots” of samba. Moreover, we can argue that Zé Keti himself already had a great deal of transit on “the asphalt”, composing his sambas while immersed in other influences. This shows us the difficulty of entering into an ontological discussion about what “real” samba is.

In any case, in all three films the directors show a lyrical and humanist look at the lower social classes and put them at the center of the cultural debate. However, it is especially important to have this discussion with Sérgio Ricardo’s Menino da Calça Branca, as this work is usually forgotten in music-related discussions about films of the time that take place in a favela, just as it was left out of the CPC film back in 1962.

1. The film also marks the debut of Dib Lutfi (Sergio Ricardo’s brother) as a cinematographer. Dib will be an essential figure of the Cinema Novo movement, becoming almost synonymous with the technique of hand-held cinematography, mainly employed in important films of the movement such as Entranced Earth (Glauber Rocha, 1967).

2. Zavattini claimed that the filmmaker should represent the lower classes as if he were looking through a hole in the wall. This was not supposed to have a purely voyeuristic goal; instead it was conceived as a means to be able to see the Other in a sympathetic way.

3. An organization linked to the Communist Party at the time.

4. Cat Skin was produced in 1960 and edited in 1961 in France (where the director had been for a small period) and ended up being added to the collective film, exhibited in 1962.

5. Sérgio Ricardo claims this in an interview with Augusto Buonicori made in March 2014 and published in: https://vermelho.org.br/2020/07/25/entrevista-de-augusto-buonicore-com-sergio-ricardo/

6. The boys in Cat Skin catch cats throughout in the city in order to sell them to the fabrication of tambourines.

7. The opening titles indicate that the boys were all residents of the Cantagalo and Pavãozinho favelas. As for the briefly mentioned racial theme, this deserves to be addressed in a separate article.

8. Making a historical analysis of Bossa Nova within the panorama of Brazilian urban popular music, Marcos Napolitano (1999: 171, our translation from Portuguese) observes that, when Bossa Nova appeared around 1959, its musicians inherited “socially rooted aesthetic and ideological formulations”, which comprised, for example, “the recognition of samba as ‘national’ music, leading many of them to propose to renew musical expression without completely breaking with tradition”. After the consecration of the movement in 1959 - 1960, from 1961 on, sectors of the Left realized the potential of Bossa Nova with a young public of students and began to politicize it. Both Carlos Lyra, composer of Cat Skin, and Sérgio Ricardo were part of the so-called “engaged” sector of Bossa Nova (Napolitano 1999).

9. This narrative aspect of the songs will be used by Glauber Rocha in his film Black God, White Devil (1964), in which the nondiegetic songs played by by Sérgio Ricardo (voice and guitar) function as a Greek choir.

10. We have employed the word “hum” here and throughout the article, although perhaps we should more precisely refer to the jazz technique of “scat singing”, which consists of singing without words or employing syllables without logical meaning and improvising. I would like to thank my colleague Alfredo Werney for the information.

11. It is important to call attention to the fact that the child’s interpretation does not reinforce the “angry” side of the revolt, but rather a certain haughtiness and acceptance of what happened.

12. Among 20 musical incursions in the film as a whole, Cíntia Onofre (2011) identifies 13 from “A Voz do Morro” in many rhythmic and melodic variations.

13. On the other hand, Zé Keti was a musician who transited in various social environments, having been invited, for instance, to participate in the famous show Opinião, in the end of 1964, which brought together both traditional popular musicians and artists of the future Tropicália, such as Maria Bethânia. Part of this show appears in the film O desafio (The Dare, 1965), by Paulo César Saraceni.

REFERENCES

Andrade, Gustavo Menezes de (2017). As populações marginalizadas nos filmes de Sérgio Ricardo. Dissertation (Undergraduation in Comunication – Audiovisual) – Universidade de Brasília.

Buonicori, Augusto. Interview by Augusto Buonicorewith Sérgio Ricardo. Revista Vermelho. Disponível em https://vermelho.org.br/

2020/07/25/entrevista-de-augusto-buonicore-com-sergio-ricardo/ Acess: 2 Oct. 2020.

Fabris, Mariarosaria (2007). A questão realista no cinema brasileiro: aportes neo-realistas. In: ALCEU, 8 (15), pp. 82 – 94.Guerrini Júnior, Irineu (2009). A música no cinema brasileiro: os inovadores anos sessenta. São Paulo: Terceira Margem.Napolitano, Marcos (1999). Do sarau ao comício: inovação musical no Brasil (1959 – 63). In: REVISTA USP (São Paulo), 41, pp. 168-187.Onofre, Cíntia Campolino de (2011).

Nas trilhas de Radamés: a contribuição musical de Radamés Gnattali para o cinema brasileiro. PhD Dissertation – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2011.