Introducing Menino da calça branca and Esse mundo é meu

Sérgio Ricardo’s debut short film Menino da calça branca (1962) and his first feature-length film Esse mundo é meu (1964) can together be thought of as sensorial film experiences1 for their unusual combination of elaborate soundtracks and experimental cinematography. Despite their striking audiovisual configuration, the two films remain underseen and under evaluated. Looking back at them with recurrent questions about how to disarticulate inequality and discrimination in audiovisual form brings forth suggestive material.

Bossa Nova and Cinema Novo composer, singer, actor, and film director Sérgio Ricardo (whose actual name was João Lutfi) wrote and directed Menino da calça branca and Esse mundo é meu. Truly a multifaceted artist, he composed the music for both films and acted in them as well. The films were shot on location in neighboring favelas; the short in Macedo Sobrinho, and the feature in Catacumba. These favelas used to be in proximity to Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas and Humaitá, areas in the affluent neighborhoods of Southern Rio de Janeiro. In the late 1960s, only a few years after the films were shot, both communities were transferred to faraway places with weak infrastructure as part of a government “cleansing” urban policy. Today, the two films offer rare visual documentation of a time when the neighborhood had more diverse populations.

Sérgio Ricardo collaborated on these films with his younger brother, the cinematographer Dib Lutfi.2 At the time, Lutfi worked as a cameraman for TV Rio. He became well known in Brazil and abroad for his technical and creative ability with handheld 35mm film cameras. Lutfi started as an amateur photographer, and then worked with the heavy studio television cameras of the time, which stood on large rolling tripod-carts. After working with this heavy equipment, Lutfi would leave behind the studio work to experiment with lighter equipment that allowed him to create unexpectedly beautiful 35 mm handheld camera movements, such as the ones that can be seen in Esse mundo é meu.3

The way that sound and music interplay in Menino da calça branca and Esse mundo é meu makes them stand out from other works of their period. Indeed, a common element between Menino da calça branca and Esse mundo é meu is the sparse dialogue throughout both films. Another notable element in the sound design of Menino da calça branca and Esse mundo é meu is their use of music not as background sound, but as narrative commentary. This approach does connect the films with other works of their time, such as Glauber Rocha’s Deus e o diabo na terra do sol (1964), a film for which Sérgio Ricardo composed and sang on the soundtrack (Rocha writing the lyrics himself).4 Moreover, the editing of both films avoids the classic configuration of synchronic sounds and images.

The production teams behind Menino da calça branca and Esse mundo é meu included participants of the intense artistic atmosphere from the early 1960s, suggesting that even though he was just starting his career in film, Ricardo took part, and in a way, marked an unusual intersection between Bossa Nova and Cinema Novo.5 Modern film pioneer Nelson Pereira dos Santos edited the short while working on Glauber Rocha’s first feature, Barravento (1962). Barravento and Menino da calça branca were both exhibited in the First Bahia Film Festival, an event that gathered the effervescent film community of the time.6 The Mozambique-born Cinema Novo director Ruy Guerra edited Esse mundo é meu.7 Guerra was part of the CPC (Centro Popular de Cultura), the cultural arm of the National Student Union that produced Cinco Vezes Favela (1962), a collection of short films that featured some members of the burgeoning Cinema Novo movement as directors. CPC did not accept Ricardo’s film to be a part of the collection, citing issues with its poetic and lyrical qualities that were not in line with their more revolutionary artistic efforts.

Scene Analysis of Menino da calça branca

Menino da calça branca tells the story of a boy who has a friendship with a local doll repairer (played by Sérgio Ricardo). The artisan has an undeclared crush on the boy’s mother, who is single and making her living as a laundry woman. He tenderly sculpts the face of a puppet to resemble that of the boy’s mother, and grants the boy’s one true wish by giving him a pair of white pants as a Christmas present.

The shoeless and shirtless white favela boy in shorts playfully somersaults in the grass until, in an upside-down position, he stops and sees the object of his desire between his open legs – a pair of white pants on a passant man (interpreted by cartoonist Ziraldo).8 This peasant man is presented through the boy’s upside-down POV. Cinematographer Dib Lutfi then pans to the sky, only to retrieve the boy on his feet by Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, following after the man in white pants. The vibration of a guitar cord emphasizes the spatial transition provoked by the pan shot. No music is used in this scene, but the unobtrusive noise of the streets can be heard on the soundtrack in an attempt to add a deeper layer of expression to the image.

In Menino da calça branca, white pants signal a dream of growing up and being fully included. It is clear that the young boy desires inclusion because, for instance, he mimics a perfectly synchronized diegetic marching band. However, we learn by the films end that white pants were inadequate for the boys daily playful life in a muddy environment, signalizing the impossibility of this naïve and depoliticized dream.

Scene Analysis of Esse Mundo é Meu

Esse mundo é meu is a particularly bold work for its willingness to confront cultural taboos. The film begins with a solemn Afro-Brazilian religious hymn. It depicts sexual pleasure. It portrays an illegal non-professional abortion (which was highly controversial at the time, and still would be today). It legitimizes the disrespect for a priest in a largely Catholic country, and it advocates for working class unionization. Bringing such a leftist agenda to a film was possible in Brazil in the pre-military dictatorship era, but after 1968 it was forbidden.

The opening sequence of Esse mundo é meu establishes the outside favela landscape with a series of long whirling shots, including many zoom-ins and pans. On the soundtrack, an orchestrated version of an Umbanda Afro-Brazilian hymn begins the film in a peculiarly solemn way, signaling an engaged attempt to bridge the gap between popular and erudite culture through syncretic non-Christian religion.9

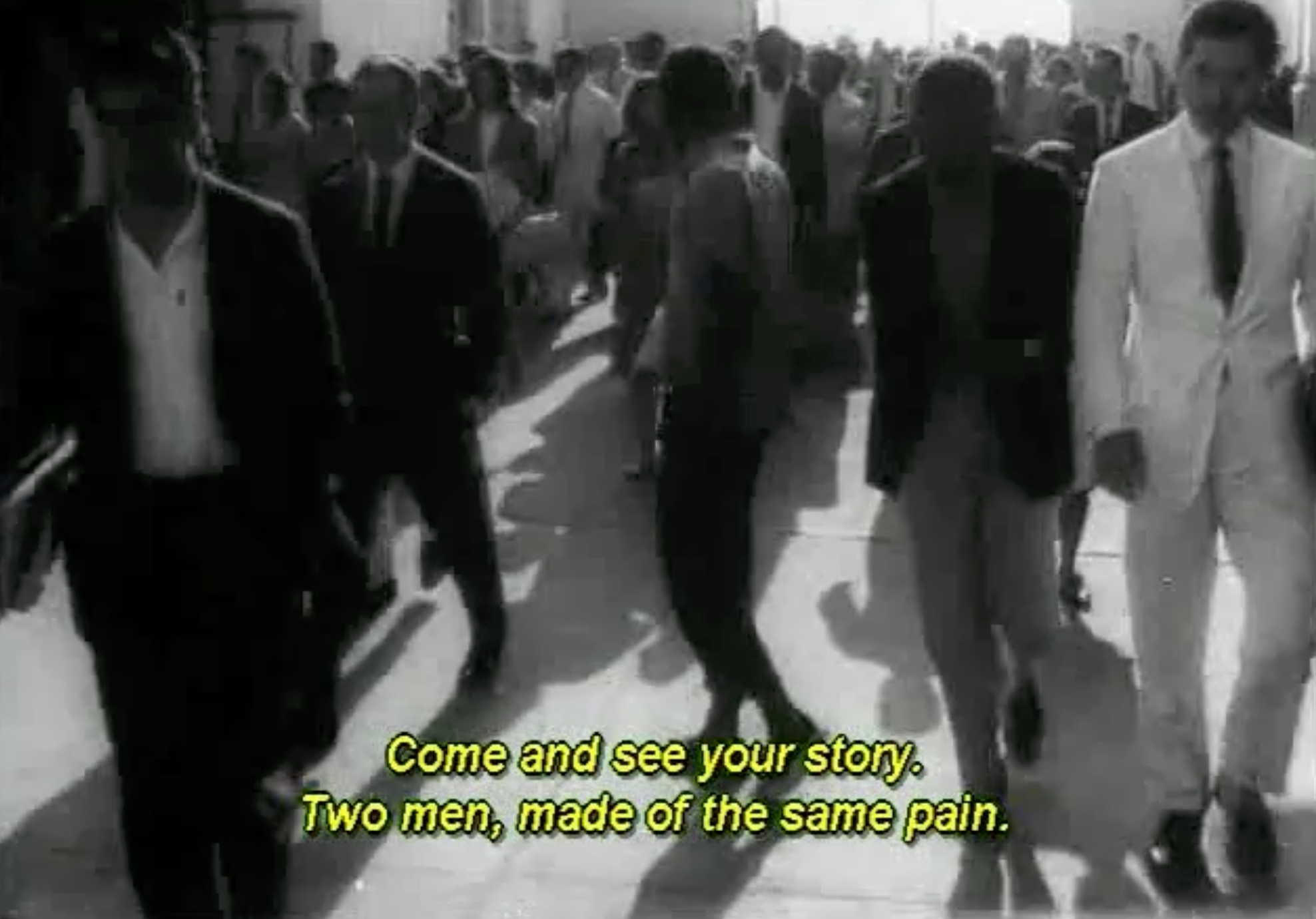

Differences between Menino da calça branca and Esse mundo é meu are the likely result of Ricardo’s attempt to incorporate some of the criticisms the short initially received for having an only white cast and for not being political enough. In parallel editing style, Esse mundo é meu tells the story of two protagonists, a white steel worker named Pedro played by Sérgio Ricardo, and a black shoe shiner named Toninho played by Antonio Pitanga. The steel worker does not have enough money to marry his beloved girlfriend Luzia. Scenes of work inside an actual small factory with diegetic noise music are one of the elements that make this film particularly distinctive.10

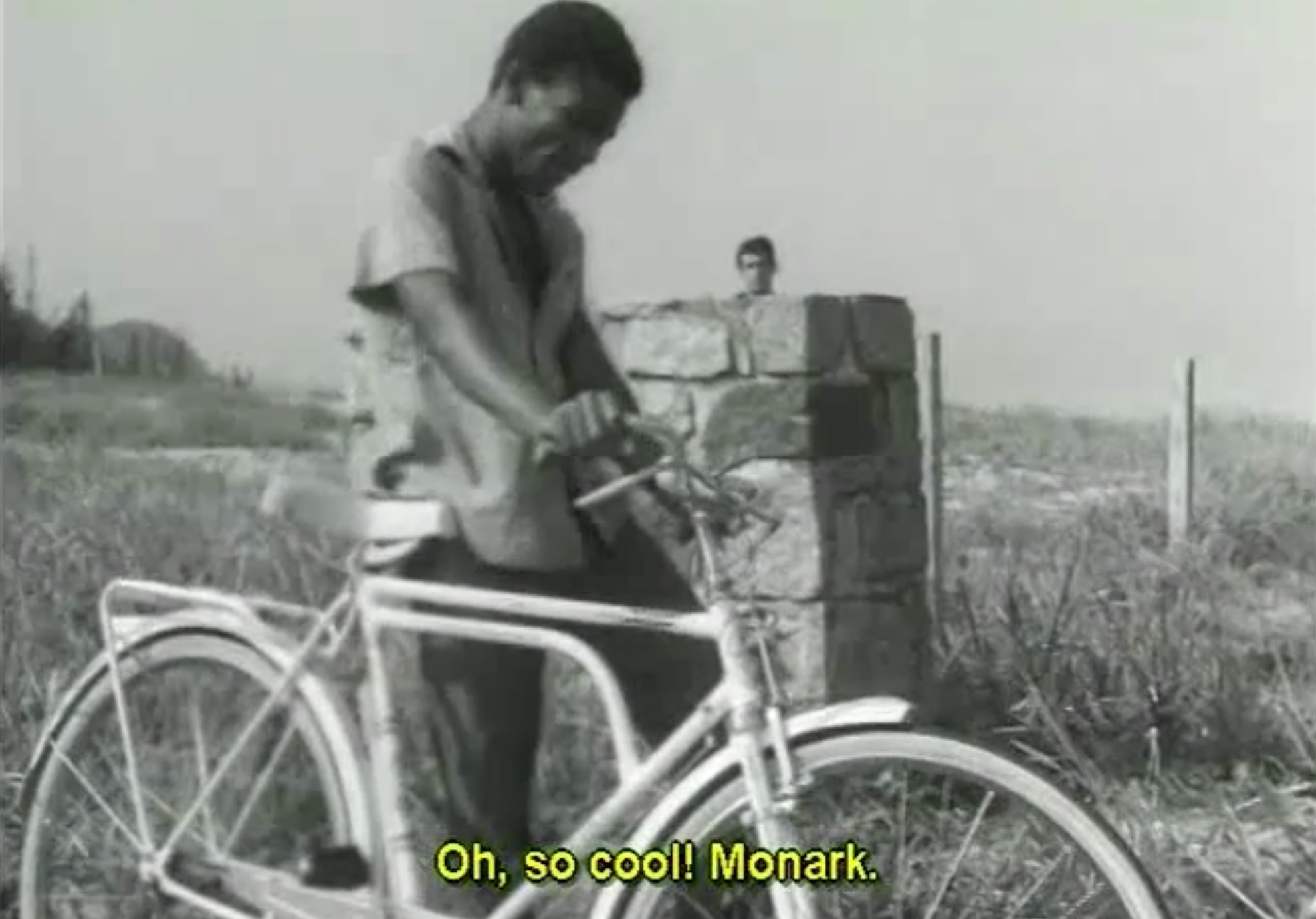

The credit sequence gives way to the introduction of Toninho, played by Antonio Pitanga. As Toninho wanders through a crowd of daily commuters on their way to work, Ricardo sings their names: “Bento, Zé, Tulão, Benedito…”. The purpose of this is to highlight that many people share the same struggles of Toninho. The song is followed by a voice-over dialogue between two secondary characters who have yet to be introduced, Toninho’s love Zuleica and her more affluent (because he owns a bike) boyfriend. From there, the film moves to the factory. Over images of daily work, a dialogue commences between the second couple, Pedro and Luzia. They discuss commemorating Luzia’s birthday by visiting all the places throughout Rio that she loves.

Both Pedro and Luzia are in love, but due to a shortage of money, they cannot afford getting formally married. Despite Pedro’s visible sadness over their situation, the couple decides to take a lovely journey through a park to commemorate Luzia’s birthday. They ride a carrousel and a ferris wheel. While on the Ferris wheel, Sergio Ricardo’s melancholic song “A fábrica” [The factory] plays on the soundtrack, the lyrics stating, “How can a woman live with a man who doesn’t have a cent?”. In this scene, the music counteracts the romantic atmosphere. Stunning shots of Pedro and Luzia circling through the air on this Ferris wheel mark the couple’s sensual affection. The camera flows with the motion of the ferris wheel as if to suggest vertigo, love and sensuality. Placed in the seat above the couple, it moves between their bodies, the sky, and other surrounding seats. Luzia moves into Pedro’s shack, she lies down, he starts to take her clothes off. A medium shot avoids showing whole bodies. The camera fixes on her face as she gets aroused.

Even though Luzia initially was the one to propose having kids, when she actually gets pregnant their lack of financial conditions motivates her decision to go through an illegal non-professional abortion. This in turn leads to her death. Pedro, now a resentful widower, leads a workers’ strike for better wages. By talking about abortion, still one of the main causes of female death in Brazil, Esse mundo é meu violates another persistent taboo. Also, it is important to note that this female character detains agency, albeit her decisions lead to her death.

A black shoeshiner, Toninho, saves money to buy a bike in order to win over Zuleica, the woman he loves. Toninho is left without his savings because his mother used them to pay for his stepfather’s funeral, so he ends up stealing a bike from a priest. Despite robbing this priest, his ending is a happy one. Having won Zuleica over, the new energetic couple embraces and turns around and around in an empty lot. The film celebrates the couple’s affection with an amazing 360 degree tracking shot, capturing their long embrace. Mid-shot, the cameraman begins to move around them in the opposite direction, intensifying the feeling of dazzling encounter.

Favela Situation Films

In his well-known critique of Cinema Novo, French-Brazilian researcher, professor, and filmmaker Jean Claude Bernardet considered Menino da calça branca mushy (“piegas”).11 Bernardet situated the short among what can be thought of as a wave of favela situation films. He considered Menino da calça branca within his broader notion of marginalism, i.e. films made by middle class filmmakers who chose to approach subjects that were not at the center of their contemporary life. Even though these filmmakers attempted to teach viewers about revolution, Bernardet observed that because they were allied with the bourgeoisie in the so-called national popular alliance, they had to avoid the main structural class conflicts. Instead of focusing on the contradictions of daily working-class life, films approached subjects such as different segments of the lumpen proletariat, favela urban inhabitants, and Northeasterner outlaws from the backlands. In doing so, filmmakers remained alienated from the working classes, despite their best intentions.12

In the early 2000s, Fernando Meirelles and Katia Lund's City of God (2002) became part of a transnational wave of what international film festivals were calling favela situation films. Some of these favela films have been immensely popular among viewers and international critics. Others have provoked criticisms for their roles in reinforcing gender, race, and class discriminations. In Brazil, these criticisms have stimulated a debate about how to disarticulate visual expressions of discrimination. Favela films deal with sensitive places and bodies, making discrimination and inequality visible within high-valued public transnational filmic spaces. In doing so, these works provoke multiple sensitive reactions among audiences.

National governments do not like what they understand to be negative representations of their beloved countries. Strong reactions to Luís Buñuel’s Los olvidados (1950) by the Mexican government, for example, already suggested that making poverty visible to a world-wide audience can incite an explosive reaction from governments. Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s Rio 40 graus (1955) was another work that was censored, this time due to its depiction of favela children struggling to survive. Black Orpheus13 (Marcel Camus, 1959), on the other hand, was a popular success in Brazil and abroad, but its artificial mise-en-scene offended the search of realism and improvisation that drove New Cinemas.

The sentimentality in Sérgio Ricardo’s films might appear to undermine predetermined revolutionary reactions against class and racial discrimination. Nonetheless, both films approach work, women, and religion in ways that were not common at the time. The female characters in Ricardo’s films present a realistic depiction of lower-class women from that period: they face the hardship of an unassisted illegal abortion, or they’re single mothers who have to work hard to support their children.

Sérgio Ricardo’s initial films enrich our knowledge about the political and aesthetic debates that animated effervescent filmmakers in early 1960s Brazil. The ways in which transmedia references inform musical choices - including an orchestrated Umbanda hymn, a band play, a song from a Chico de Assis play, atmospheric noise – and collaborations by other fellow artists, and filmmakers suggest the potential of thinking about the complex web of art production, and circulation, within the arts community of that period.

In the two films, sound and image rhyme in unexpected asynchronism in ways which combine sensuality, complex visual movement, silence, noise, and instrumental/sang explanatory lyrics. This audiovisual sensory quality might disarticulate common sense audiovisual class, race, and gender discrimination, and open horizons for change.

1. Elsaesser, T. a. M. H. (2009). Film Theory: An introduction through the senses. London, Routledge

2. Sérgio Ricardo would go on to collaborate with his brother Dib Lutfi on his next two feature length films, Juliana do Amor Perdido (1970) and A Noite do Espantalho (1974). The two brothers collaborated with Glauber Rocha in Terra em transe (1967). Lutfi would go on to work with Eduardo Coutinho, Domingos de Oliveira, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, Walter Lima Jr., among others.

3. Dib Lutfi took Arne Sucksdorff’s 1962-63 film course, which first introduced NAGRA direct sound equipment to filmmakers in Brazil. In 1963-64, besides working on his brother’s films, Lutfi assisted Sucksdorff on his feature Fábula or Mitt hen är Copacabana (1965). The differences between Sucksdorff’s “academic” tripod and lightening and Lutfi’s hand held cinematography and natural lightening techniques are remarkable. The differences suggest the varying ways in which the local appropriation of foreign techniques can result in different aesthetics. Hamburger, E. (2020). "Arne Sucksdorff, professor incômodo no Brasil." https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7287020 (access 11/15/2020)

4. Glauber Rocha created a cordel style song and asked Sérgio Ricardo to listen to his recordings of popular Northeasterner repentistas, who sing, and play the rabeca in popular markets and other public spaces. Their compositions absorbed ongoing events and figures, mixed with old Iberian structures. While this folk style was familiar to Rocha, Ricardo was introduced to cordel to compose the music. The result is a well-known song that managed to bring popular culture to an experimental film. Xavier 1999 [1997], Carvalho 2011, Debs 2014

5. Leal, H. (2008). O Homem da Montanha, Orlando Senna. Carvalho, M. d. S. S. (2003). A nova onda baiana: Cinema na Bahia 1958-1962. Salvador, Editora da Universidade Federal da Bahia.

6. Although Guerra is credited for editing the film, and not credited for the song, his dense and detailed biography mentions his friendship with Sérgio Ricardo and authorship of the lyrics of the song “Esse mundo é meu”, but does not mention the editing work on Esse mundo é meu. Even though the film is named after the song, only the main chorus from the original song is there. The song would reverberate as it was recorded by Sergio Ricardo in the film’s album, and later by the very popular singer Elis Regina. Borges, V. P. (2017). Ruy Guerra, paixão escancarada. São Paulo, Boitempo.

7. An emblematic example of this dynamic occurred in 2008, with the presence of the Executive Director of the Cinemateca Brasileira at the 3rd annual CineOP. The theme of CineOP that year was National Audiovisual Preservation Policy: Needs and challenges. Throughout the event, the Executive Director took a firm stand on opposing the articulation of other audiovisual heritage institutions with the Ministry of Culture’s representatives, and the creation of the Brazilian Association of Audiovisual Preservation (ABPA).

8. Ziraldo also designed the film’s credits. He also appears in Esse mundo é meu; Visual artist Lygia Pape designed the credits for the feature.

9. This Umbanda hymn says Oxalá / meu pai / Tem pena de nós /Tem dó / A volta do mundo é grande / Seu poder é bem maior (Oxalá/ my father / have pity on us / have mercy /the turning of the world is large /but your power is much larger) Maestro Gaya is credit for the film’s music, therefore this and other orchestrations are his.

10. Esse mundo é meu includes “ Canção do último caminho” from the cordel playAs Aventuras de Ripió Lacraia, written by CPC playwright Chico de Assis. The play is featured in the sound track to indicate that Luzia died: “Neither hunger nor temptation, neither pain nor love, His soul became a little bird, beautiful flight took off, He went far away on his way, He went to heaven to fly there.” (p. 17)

11. Bernardet, J. C. (2007 [1967]). Brasil em tempo de cinema, São Paulo.

12. See for example Cardenuto, R. (2008). Discursos de intervenção: o cinema de propaganda ideológica para o CPC e o ipês às vésperas do golpe de 1964. PPGMPA. São Paulo, Universidade de São Paulo. Mestrado. , Cardenuto, R. (2014). O cinema político de Leon Hirzsman (1976-1983): Engajamento e resistência durante o regime militar brasileiroibid. Doutorado.

13. Based on an original play by Brazilian poet, and diplomat Vinícius de Moraes.