My Name is Tonho (1969) was Ozualdo Candeias’s big follow up to his well-received debut The Margin (1967). The earlier movie announced a radical São Paulo cinema and is often treated as the starting point of the so-called Cinema Marginal movement. But the film can also be seen as a dirty city symphony that was closer in spirit to Mario Peixoto’s Limite (1931) than anything Cinema Novo was doing at the time. The self-conscious and Avant Garde tendencies of The Margin made it popular with critics. Tonho, despite its own radicalism, was perceived by critics as a confounding retreat into commercialism for Candeias.

Tonho began as a film commissioned by producers who wanted a Brazilian western, something closer in style to the Italian westerns that had become popular at local theatres during the time. Here lies Candeias’s paradox and is the reason why My Name is Tonho is in many ways a better introduction to his cinema than the artier The Margin. Candeias was a radical filmmaker, but one who felt comfortable among the more populist side of Brazilian film. He made his home at Boca do Lixo, the São Paulo district where most of the exploitation output in Brazil would be produced between the late 60s and 80s, sex comedies mostly, but also crime films, horror, melodrama and its share of westerns. Even in the late 80s when Boca had descended into porn, Candeias still made a point of remaining based there. The proximity with those movies, and often sharing some of the same talent, was important for what Candeias was after.

Much like Samuel Fuller, Ozualdo Candeias was often mistaken as a primitive filmmaker. Like the American master, Candeias learned early to do things his own way, he liked stories he could sink his teeth into but had little uses for standard dramatic structure (the plot description for Tonho makes it sound far more straightforward than it is) and he preferred an immediate style that reacted to characters and their milieu much more than a traditional aesthetic approach. Candeias was a gifted environmental filmmaker with a knack for making his locations count and describing specific subcultures. He was also completely uninterested in setting his movies in places other filmmakers were using. Candeias’s past as a truck driver has often been used as a source of mystification, an attempt to turn him into a mythic figure, a naive common man with a camera. It is true that he had a much more blue collar origin than the usual middle-upper class celebrated Brazilian filmmaker (true for a lot of people working at Boca do Lixo at the time), but Candeias actually studied film, his main professor Maximo Barro edited The Margin, and was a good technician who sometimes acted as a near one man film crew on his films. Candeias's style had much more to do with a need to arrive at a fair representation of Brazil’s violence and poverty than some sort of naive accident.

There is a long tradition of Brazilian westerns. The country’s first international success was Lima Barreto’s The Bandit (1953) and it started the cangaceiro movie tradition that remained a strong local industry for a long time. Barreto’s assistant Carlos Coimbra, for example, made a career out of making these types of films. Those movies usually were set around the cangaceiro years at the start of the 20th century and take place in the Northeast, while being made by Southeast filmmakers. Glauber Rocha’s breakthrough Black God, White Devil (1964) can be described as an answer to those movies (Rocha once dismissed the genre saying São Paulo filmmakers couldn’t get Bahia’s light right).

This tradition is a useful reference point to My Name is Tonho, since Candeias completely dismisses it. Brazilian westerns often work hard to create Brazilian myths out of recognizable genre beats. Candeias does the same, but he forges his own path that has only some resemblance to genre as we know it (Fordian mythmaking couldn’t be further from his interests). Tonho certainly has known genre motifs - a family massacre, a man after revenge, a gang that terrorizes the region, and it even ends with a duel payoff between the avenging hero and the violent bandit. However, almost nothing about how it plays follows expectations. Candeias approached Tonho not as a reconstructed American genre film, but as a countryside drama. In this, it is actually closer to a John Ford/Harry Carey silent western, imagining situations that were still recognizable to a local population instead of what the post war western would become, where familiarity with people and situations matter more than narrative motifs. Tonho replaces the American old west for São Paulo country life. Its main interests are life and rhythms of small towns and farms of the area. Sometimes a shootout or a fistfight will break out, but it is telling that so much of it concerns people simply riding horses.

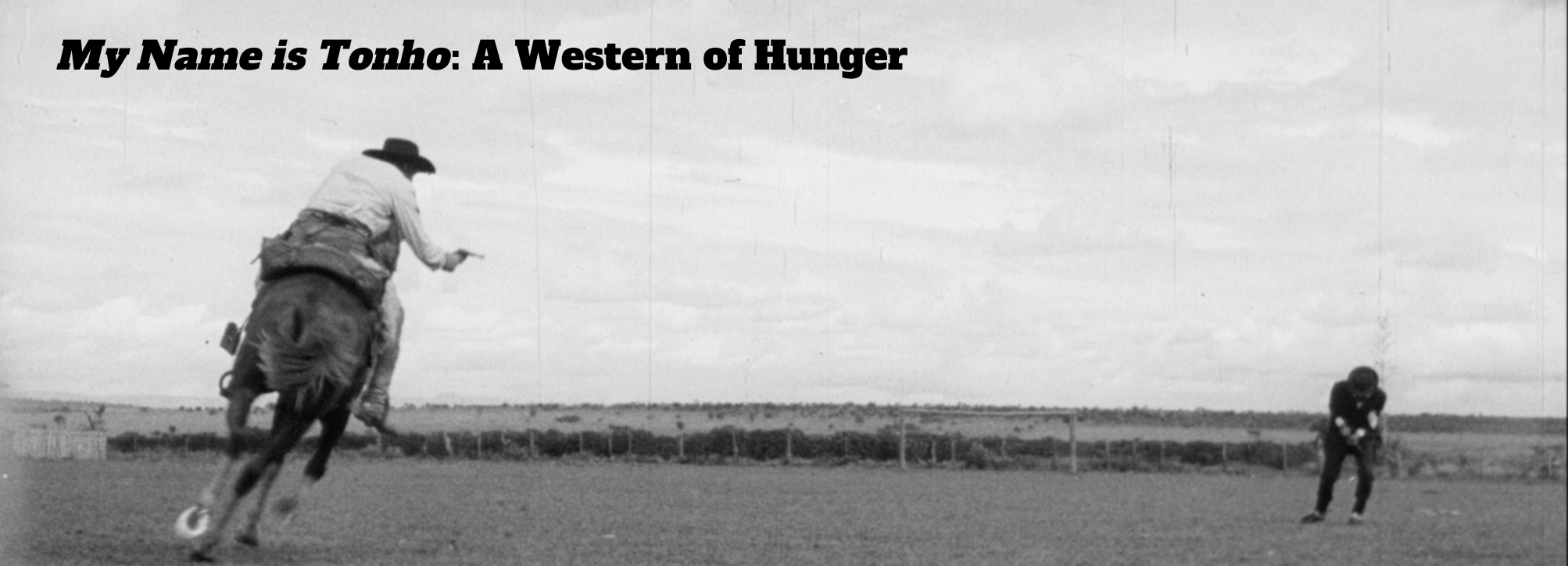

It is exemplary how much the cast of Tonho fit their surroundings. Candeias is great with faces, often filming them in closeup while desperately laughing. He is even better at giving actors things to do that make sure they are physically immersed in their character’s realities. The action scenes are often clever - the final duel is set so Tonho is riding an always moving horse and the dangerous Manelão is stuck at the center that the action axis keeps returning to. This provides a reverse of expectations as the hero has an upper hand, but also plays up the narrative logic until this point, as Tonho had been the one driving towards Manelão throughout the film. The violent camera movements, tight action and often offbeat editing suggest some of Rocha’s approach in his couple of Cangaço movies.

Indeed, the two 1969 Brazilian movies that My Name is Tonho brings most to mind are Rogerio Sganzerla’s The Woman of Everyone and Rocha’s Antonio das Mortes. Like Sganzerla’s film, it is a follow up to a successful debut that embraces a popular genre (sex comedy) and that uses its familiarity as a letter of intent while aggressively deconstructing its patterns and pushing them towards an apocalyptical end (it might be worth pointing out that Tonho cinematographer Peter Overback shot Sganzela’s debut The Red Light Bandit).

Antonio das Mortes and My Name is Tonho could not look further apart. Rocha's sequel is an epic in color made with international money. Similar to Tonho, it is a popular movie by a “difficult” filmmaker on specific radical terms, but the surface is much more mainstream with great colors and panoramic choreographed action. Both films are clear discourses on violence as it dominates the Brazilian backwoods and how they also sustain a political status quo. Tonho has a more direct address and Candeias remains closer to the action. There are plenty of similarities between Rocha and Candeias, but the latter inhabits hunger in a more direct manner. The protagonists Antonio and Tonho are outsider gunfighters who end up set against local forces, but their tragic non-belonging comes from opposite directions. Antonio is a stand-in for the left leaning middle class intellectual with their split class loyalties, Tonho is driven by retribution and extinguishes as soon as he realizes it. He suggests everyday violence instead of the many forces that organize it.

The wonderful choreographed final scene with Tonho getting back on his horse and leaving town for good, everything unchanged, is made remarkable by the sudden shift of focus that explains Candeias's preoccupations going from the gunfighter figure to the sister he leaves behind. She belongs to the land, to its violence as it will continue to be enacted time and again. It is to that world that Candeias pledges his loyalties that he will remain committed to find new ways to represent through the next quarter of century.