The Filmmaker and the Restoration

Goldsmith, watchmaker, photographer, inventor, filmmaker, projectionist, musician and owner of a movie theater, the restless Ludovico Persici was born in 1899 in Alfredo Chaves, a municipality of Espírito Santo. Persici was the firstborn of seventeen offspring of whom ten survived. In 1924, he married Eliza Fernandes D’Ávila, the fifth daughter in a family of seven. The couple had no children.

Curious and gifted with remarkable intelligence and invention skills, Ludovico was still in his early years when he started attending the goldsmithing and watchmaking workshop of his father, Erasmo Persici, an Italian immigrant from the province of Parma. He handled tools and disassembled and assembled devices in order to better understand how they worked. According to his brother and biographer Arlindo Persici, it is likely that ingenuity and art manifested in Ludovico Persici around the age of 10 during the construction of the Vitória–Cachoeiro de Itapemirim Railway. The boy mimicked or tried to reproduce each stage of that construction by finding a gully to place a miniature of cuttings, tunnels, crossties, and rails… Nevertheless, going against his father’s authority and not enduring the monotony of his third year of primary school, Ludovico abandoned his studies and ran away from home several times. Ludovico was so hard to pin down that the strict father had to undertake a marathon in search of him.¹

Persici was young when he discovered cinema, only 14. In 1913, he was taken to Rio de Janeiro to become a goldsmith and to improve his skills in the art of watchmaking alongside a great Spanish master. He spent two years in Rio. Of all the novelties that the big city had to offer, the cinematograph was the one that fascinated him most. He became a frequent visitor to weekend movie house screenings, often watching the same films over and over again.

A pioneer in every respect, Ludovico Persici is the driving force behind the Cine Memória Capixaba program, whose mission is to discover and spread the diversity of Espírito Santo cinema and to find ways of preserving it. Persici’s only surviving film, Cenas de Família, was considered lost until PhD researcher José Eugênio Vieira discovered it while assessing primary sources for a historical study on Castelo, a municipality located in the state of Espírito Santo. The film was subsequently restored from 2004 to 2010 with funding from the Secretary of Culture of the Government of the State of Espírito Santo (Secult-ES).2 The process was carried out by the Secretary’s Coordination of Cinema and Video under the framework of the project Cine Memória Capixaba.

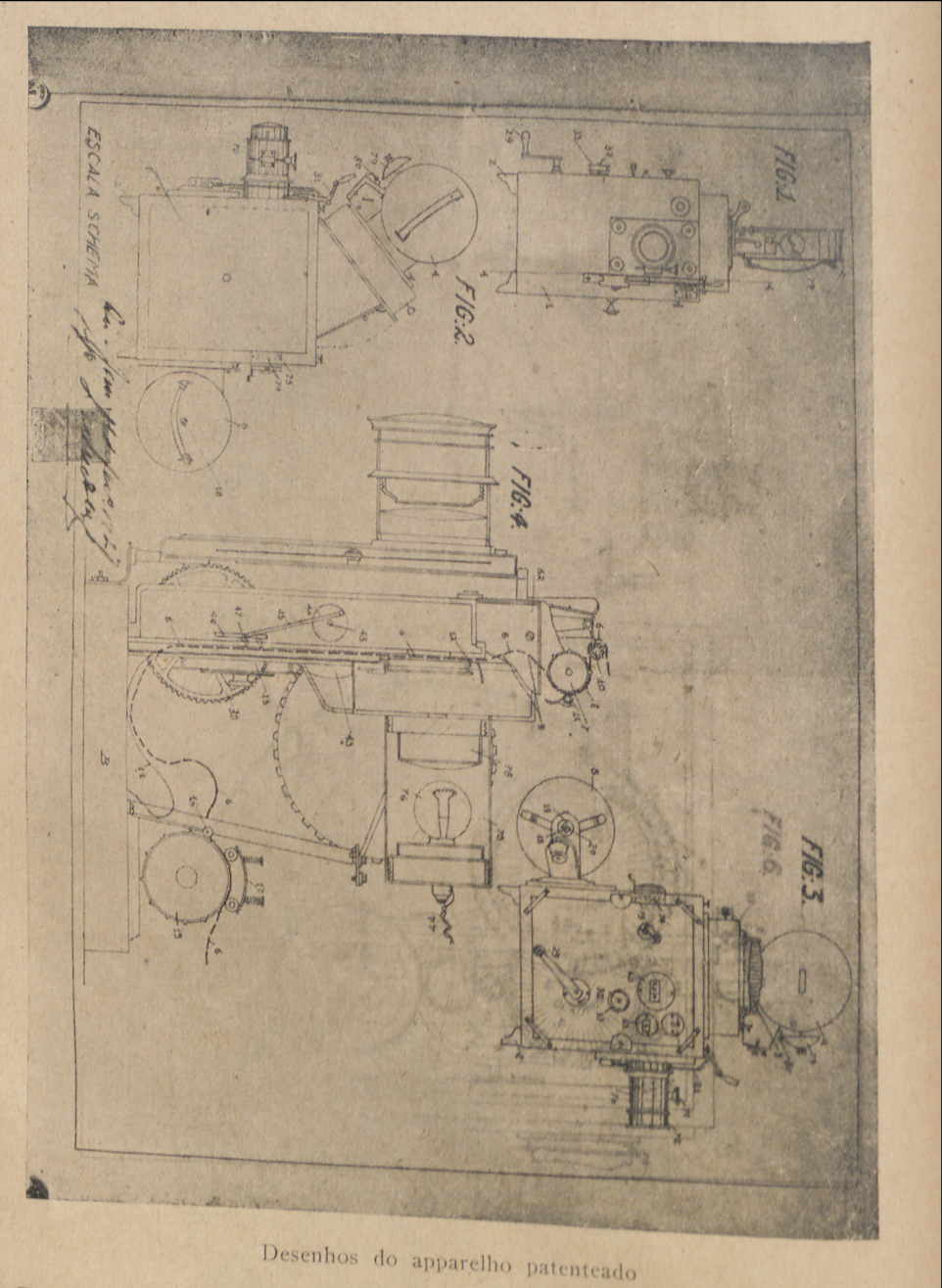

The original 16mm reversible film print of Cenas de Família was found wrapped inside a newspaper in a plastic bag. The print was stuck together and dried out like a brick. As far as we could tell upon first looking at the print, it was the negative of the first film shot with the “Cinematógrafo Guarany” [Guanarany Cinematograph], the camera Ludovico Persici built and patented at the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Commerce, in Rio de Janeiro in 1927. According to the Dicionário Histórico Fotográfico Capixaba website, the machine “...filmed, projected, copied, and measured the film length frame by frame. It was also equipped with a bell, which announced the end of the cinematographic screening”.3 Persici managed to put all these features into a single portable device.

I was aware of how historically important this film was and soon realized that a major financial investment and the right technology would be needed to restore the work. Months after we discovered the film print, Secult-ES partnered with Brazilian film archives4 to put on Mostra de Cinema de Arquivo: A Censura e o Cinema [Archival Film Screening Series: Censorship and Film]. The screening series took place in 2004 with the support of local and institutional press, achieving success among audiences. In addition to this program of archival films we put on four thematic discussion panels: Censorship in Brazilian Cinema, Cultural Resistance in Espírito Santo, Public Policies for Audiovisual Preservation and New Technologies Applied to Preservation.

One of the films shown at this screening series was O Sonho e a Máquina, a documentary by Alex Viany about Ludovico Persici. The film archive of the Arquivo Público Estadual do Estado do Espírito Santo [Public Archive of the State of Espírito Santo] holds a 16mm print of the film. Made in 1974, this film provides insight into Persici’s importance as well as Espírito Santo’s presence in the history of Brazilian cinema. Based on an investigation conducted by journalist Rogério Medeiros, this film was gorgeously shot by Hélio Silva, distributed by Embrafilme, and produced by capixaba Ney Modenesi.

Technicians Clóvis Molinari and Mauro Domingues, from Arquivo Nacional, and Patrícia de Fillipi, from the Cinemateca Brasileira, participated in the Public Policies for Audiovisual Preservation and the New Technologies Applied to Preservation panels as Secult-ES’s special guests. Their technical support was key in allowing us to appoint Rio de Janeiro-based Labo Cine do Brasil as the laboratory to undertake the restoration of Ludovico Persici's film. The decision to work with Labo Cine was grounded in the historical importance of this film, the urgency to work on it, its poor conservation status, and the specific technology required in the restoration process. Cenas de Família received its name at Labo Cine, following the identification of frames portraying scenes of everyday family life.

The restoration work on the Cenas de Família’s print started in 2005 and lasted about three years. By the end of that time, a master print and an internegative were produced as a basis for the final copy in 16mm. This copy was digitized and later donated along with the internegative to the archives of Arquivo Público do Espírito Santo.

Cenas de Família’s first screening took place in August 2008 at the Anchieta Palace, headquarters of the State Government. The screening took place together with the release of the second edition of the book História do Estado do Espírito Santo [History of the State of Espírito Santo] by José Teixeira de Oliveira. A digital copy of the film was scored with a collection of jazz songs and then projected at this event, which was coordinated by the Office of the Civil House of the Government of the State of Espírito Santo. The second screening of Cenas de Família took place in 2009 at the opening of Projeto Mova Caparaó (6th Mostra de Vídeo Ambiental do Caparaó). For this screening, the restored film print was shown and the projection of the original silent copy was backed up by the accordion of Mirano Schuler. The event was carried out by Secult-ES in the municipality of Alegre, under the coordination of the author of this text.

The Railways of Cenas de Família

The e-mail that first notified the beginning of the restoration process of Cenas de Família came along with a handful of preliminary moving images. Attached, we found two train sequences whose combined running time amounted to about a minute. Throughout that week and the following one, I watched these sequences several times, frame by frame, in search of a clue or remnant that could lead me to their author. Immediately, a particular image frozen on the screen seemed to echo Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat, the Lumière Brothers’ 1896 film.

Could Ludovico Persici's “A Chegada do Trem” [Arrival of a Train] in Cenas de Família be a premeditated quote? A tribute to the pioneers – from one inventor to a duo of inventors – each with their own cinematograph and the train station of their respective time? For Ludovico, there was a 33-year gap between himself and the Lumière Brothers’. He was then 28 years old.

The Caravelas Railway was the first train segment built in Espírito Santo, still in the Provincial period, and its images in Cenas de Família are its oldest records. The Viscount of Mattosinhos, who owned Companhia de Navegação and Estrada de Ferro Caravelas [Caravelas Railroad and Navigation Company], was responsible for the creation of the railway. The construction of the railway route took less than two years. The work began in January 1886 and was concluded in September 1887.5 The construction was for the transportation of coffee from the region of Alegre and Castelo to Cachoeiro de Itapemirim. A vessel loaded with the product would then head to the Port of Itapemirim and finally be bound for Rio de Janeiro, where the coffee would be exported.

The Caravelas Railway had come under the control of company Leopoldina Railway in 1907. It was 71 km long, starting from Cachoeiro de Itapemirim and splitting into a 50km long branch line to Alegre and another 21km long line to Castelo. The latter is the one documented in the film.

In the same year of 1927, Ludovico Persici was living in Conceição do Castelo, in the Cachoeiro de Itapemirim district. He was living there along with the “Jovens Castelenses” [young girls from Conceição do Castelo] documented on the street and on the beach of Marataízes. Also living there, presumably, were his three friends on the train, who are there throughout the whole trip and in other ventures recorded by Ludovico in the film.

By the end of that decade, coffee production in Espírito Santo had developed to the extent that the state had become the fourth-ranked producer in the country. The south of the state played a major role in this achievement on account of the coffee production levels within the municipality of Cachoeiro de Itapemirim.

In 1928, the county of Castelo was established and the district of Conceição do Castelo was made part of it, gaining the status of a village. Its population descends predominantly from Italians coming from Italy’s northeastern provinces. Colonization originated particularly in Serra do Castelo, which would later lend the city its name. It was so called due to the formation of hills and valleys that resembled European medieval castles.

While observing the railway stations as identified on the train’s path, we find the following sequence: Coutinho (00’52”),6 Castelo (02’54”), Santo André (04’02”)7 and Conduru (13’08”). Except for Coutinho, these stations are spotted from behind or along the moving train. As the characters disembark at Coutinho Station, this allows us to surmise that they came aboard in Castelo, towards the municipality of Cachoeiro de Itapemirim.

We can distinguish two films in this location: a fiction and a documentary. In the fiction, the driver in uniform gets off the train surrounded by a cloud of steam. A man in a jacket and tie awaits him by the line. A uniformed train agent comes close to both of them. They head towards a locomotive stopped on another railway line, in the opposite direction. A man in a suit is on the ground, clinging to the locomotive's track cleaner. We then notice a very brief turmoil between the driver and this man, staged for the camera while it drifts to Coutinho Station. On the station platform, a man in a suit goes down the ramp towards the camera. Wide shot of Coutinho Station. A three-car passenger steam locomotive stops at the railroad.

In the fiction, the driver is played by Ludovico Persici himself. The man who goes down the station ramp and the man in a suit whom we watch clinging to the locomotive are his friends and actors who accompany him on the train journey. Sadly, this eventful external sequence at Coutinho Station is damaged and the content of the scenes has undergone great loss. The external shots of the Coutinho Station are beautiful, either for the fiction or for the documentary “A Chegada do Trem”.

This is the only location where the camera is off the train. In addition to the above-mentioned shots, two fixed shots recorded as supporting material display the four friends on board (including Ludovico Persici, the one who wears a hat) standing outside the passenger wagon (04’57”). They were probably filmed either on this very set or at a train stop at Conduru Station (13’08”). The camera, which records most landscapes of this route, shapes a subjective gaze of the travelers.

This is the only location where the camera is off the train. In addition to the above-mentioned shots, two fixed shots recorded as supporting material display the four friends on board (including Ludovico Persici, the one who wears a hat) standing outside the passenger wagon (04’57”). They were probably filmed either on this very set or at a train stop at Conduru Station (13’08”). The camera, which records most landscapes of this route, shapes a subjective gaze of the travelers.

We now join Ludovico and his three friends on a trip down the Rio-Petrópolis Highway, the first paved highway in the country and a landmark of national engineering. The Rio-Petrópolis Highway was only officially opened in August 1928 by President Washington Luiz, the last president of the República Velha [Old Republic], deposed by the Revolução de 30 [Revolution of 1930].

We believe that the images shot for “A Chegada do Trem”, included in the rough cut of Cenas de Família, document the trip of Ludovico Persici and his friends to copyright his Guarany Cinematographic Apparatus in Rio de Janeiro in 1927. The biographical notes published on Ludovico Persici’s filmography usually highlight Bang-Bang, a film which was scripted, produced and directed by Persici in 1926. Persici used his own friends as actors in order to put his invention into practice. He thus became the cinema pioneer in Espírito Santo and we might even say one of its precursors in Brazil.

1. Lopes, Almerinda S. Memória Aprisionada - a visualidade fotográfica capixaba: 1850/1950. Vitória, Edufes, 2002.

2. TN. Mentions to local institutions, venues, grant and cultural programs and artistic or research works throughout this text may be directly translated to English, when this seems accurate and adequate. Otherwise, in case the original name in Portuguese is to be registered, necessary translation will be found in brackets for better understanding.

3. https://dicionariofotograficocapixaba.blogspot.com/2018/05/ludovico-persici.html?m=1

4. Institutions include Arquivo Nacional [National Archive], Arquivo Público Estadual do Estado do Espírito Santo (APEES) [Public Archive of the State of Espírito Santo], Cinemateca Brasileira and also the Legislative Assembly of the State of Espírito Santo (Ales).

5. Ferreira, C, S. Estrada de Ferro Caravelas: Trilhos pioneiros da trajetória socioeconômica do Sul do Espírito Santo. 2015. 125f. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em História, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2015.

6. Former Mattosinhos Station (later called Coutinho). A tribute by Leopoldina Railway to Governor Henrique Coutinho, on account of transferring the Caravelas Railway.

7. Santo André Station (later called Aracuí, which is currently the name of a neighborhood in Castelo).