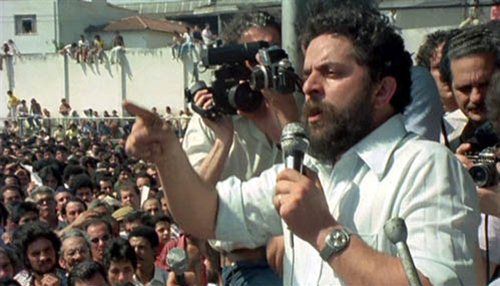

In 1978, after 14 years of repression and silence imposed by the civil-military dictatorship, workers at the Scania truck factory in São Bernardo do Campo (SP) declared a general strike demanding a 20% salary increase, a percentage above the readjustment proposed by the government. This act triggered a cycle of strikes by workers in São Paulo and its periphery, which took place between 1978 and 1980, mobilizing a broad spectrum of Brazilian society in the struggle for wage increases, union freedom and better living and working conditions. A key moment in the history of the struggles of the workers and the poor of the New Republic, the strikes in São Paulo can be considered the origin not only of the emergence of the so-called New Unionism, the Workers' Party, the Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT) and leaders such as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, but also the origin of the dreams of a new democratic Brazil made with and for workers subordinated by the economic and political elites. The working class emerged as a new social actor, with a disruptive force that irreversibly transformed Brazilian society.

But the strikes undertaken by São Paulo metalworkers did not happen overnight. As witnessed by the filmmaker and social scientist Renato Tapajós - who is participating in the Cinelimite program Raised Fists, Camera Rolling: The São Paulo Metallurgical of 1978-1980 and the of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva with the films Acidente de trabalho (1979), Trabalhadoras metalúrgicas (co-directed by Olga Futemma, 1978), Greve de março (collective direction, 1979), A luta do povo (1980) and Linha de montagem (1982) -, the confrontation of the strike movement with the so-called “pelegos” (that is, the leaders of the labor unions under the intervention of the military) took shape from the grassroots work of clandestinely organized workers since the late 1960s. From the factory floor emerged what was commonly called an authentic or combative unionism. Dissatisfied with the terrible working conditions, the low wages and the political ineptitude of the labor unions under the intervention of the military government, this network of workers acted towards the transformation of the labor union structure and, by doing so, they ended up shaking the structures of subjection of the Brazilian working class - without, of course, extinguishing it once and for all.

The union structure at the time had been implemented decades before by the government of Getúlio Vargas, in a way that presents a clear conflict of interests between the working class and their employers. With the military coup of 1964 and the subsequent federal intervention in the labor unions, this model of corporatist unionism intensified. In the mosaic of works presented in this program, we repeatedly find the discourse that unions under military intervention represented the interests of employers and multinationals to the detriment of the working class. The generation that mobilized after 1978 and whose memories we watch in this programrose up against this petrifying configuration. Lula and the workingclass as a political and culturalcharacter emerged, therefore, from the depths of the repression of the military regime.

This socio-political upheaval caught the attention of a number of Brazilian documentary filmmakers, who joined labor unions and social movements to uniquely record this process of strikes. The account of one of the filmmakers who make up the group of auteurs in this program produces a strong image to think about the contradictory feelings that affected the filmmakers engaged in this situation. When Sérgio Péo faced the strength of the strike movement, he thought: “Damn! The dictatorship is over!”. “Adventure” is the term Péo used to describe what this heterogeneous group of documentary filmmakers was doing at that moment that represented the requiem of the military regime.

In an essay entitled "Worker, an emergent character", Jean-Claude Bernardet identifies a symptom of Brazilian cinema. The example was excluded from the cast of characters in national cinema until the mid-1970s. In its place, the figure of the trickster and the vagabond, for example, prevailed. And when Cinema Novo implemented a critical attitude towards Brazilian society, the sertanejo was the character chosen as a symbol of the oppressed of capitalist society. The lack of an urban working class perspective in national cinema shows how filmmakers were reluctant to think about the urban world from the point of view of class society. But that changed during the intensification of capitalist contradictions under the military regime and, in the 1970s, especially during the period of the São Paulo metallurgical companies, the worker suddenly appears as a character in several films, and an expressive portion of this filmography is found in this program. Bernardet's thesis is that the advance of capitalism in Brazilian society was also expressed in the audiovisual sector, which contributed to the organization of filmmakers as a social class. The loss of income and status brought the filmmakers closer to the working class, a configuration that created favorable material and ideological conditions for the approximation between the two social groups.

The first two documentaries of the Cinelimite program present us with the context of labor relations and the precarious working conditions in factories on the outskirts of São Paulo. Our adventure through this mnemonic labyrinth begins in Acidente de trabalho (Renato Tapajós, 1979). Like other works by Tapajós, this documentary has its feet on the city streets. The first image that takes shape in front of us is precisely an urban view: we see the movement of workers in a metropolitan center while a voice tells us its misfortune. The reports collected by the documentary filmmaker narrate the precarious working conditions and the negligence of employers and the government that symptomatically led to a series of work accidents that immobilized the bodies of several poor workers on the outskirts of São Paulo.

The film records memories of events that precede the great metalworkers' strikes and shows them as building material for the popular fury that took shape in the strikes of 1978, 1979 and 1980. Everything happens as if Tapajós was trying to record the material reasons for the explosion of the strike movement of the late 1970s. This work serves, therefore, as a piece that brings together memories of the terrible working conditions in Brazilian factories during the Military Dictatorship that ruled the country from 1964 to 1985.

Trabalhadoras Metalúrgicas (Olga Futemma & Renato Tapajós, 1978) is a forgotten gem of Brazilian cinema. A film made during the 1978 Metallurgical Women's Congress that records moments of the event articulated to scenes from the lives of female workers in ABC Paulista. The documentary thinks about a fundamental issue for the history of social movements: the struggle for women's rights. We follow the life and political action of feminist fronts inside the factories. As one of the activists tells us, the aforementioned congress was “a school” for a whole generation of workers who, from then on, intensified the demand for equal wages and better working conditions in a struggle that radically questioned the patriarchal order of labor relations in Brazilian factories.

In Braços Cruzados, Máquinas Paradas (1979) we find the history of the political tensions of São Paulo unionism shortly before the establishment of the new board headed by Lula and his companions. It is a film that presents the internal contradictions of the trade union movement at a turning point in the struggle of Brazilian workers. The documentary by Roberto Gervitz and Sérgio Toledo reveals the movements of the campaigns for the presidency of the ABC metalworkers' union in a context of confrontation between two paradigms of unionism. On the one hand, the union heir to the labor movement of Getúlio Vargas, on the other, what was later called Novo Sindicalismo. In summary, the first model, hegemonic until 1978, represents the employer class through union leaders who offered workers an ineffective assistance system, serving more to immobilize the struggles of the working class than to leverage them. The second orientation, as already mentioned, fought for the right to strike as the main negotiation tactic with the bosses and the government - it is a union organization that emerged organically within the factory.

In addition to the history that we get to know through the documentary, I must emphasize that this is a film of landscapes and physiognomies. A work that seeks at various times to record machinic views and portraits of workers from the underworld of São Paulo's factories. Despite being well-intentioned and clearly positioned on the side of the workers, the film has a problematic feature that should be mentioned. There is a clear gap between the documentarians who film and the workers filmed, that would not be a problem for critics if it did not generate complications of documentary mise en scène. The film observes the workers from afar as if looking at something exotic. Their successful search for picturesque physiognomies and landscapes leads them to a stylization that objectifies the workers. But the film is not limited to this matter and to affirm this would be to close one's eyes to the film’s plastic and discursive force. The montage energizes the spectator's body, as it follows a dialectical orientation that articulates the past of corporatist labor with the emergence of the new ABC unionists, in addition to confronting oppressors and oppressed. This shock produces a veritable amalgamation of times that, together, take the form of a bomb. The dialectic between images of the intervening unionists and the workers' opposition at the end of the documentary intensifies the dialectical character of the film, having as a synthesis the appearance of a crowd of workers in what was, at the time, the biggest strike since the military coup. The voice ends the narration explosively: “1978: the union structure begins to fall”. The contradictory writing of Braços Cruzados, Máquinas Paradas makes it a challenging object of study for the analyst.

Greve (João Batista de Andrade, 1979) builds an overview of the strikes of 1979, following the thread of events since the explosion of the strike movement, passing through the arrest of Lula and other union leaders, and ending with his release and the resumption of the struggle with the speech at the Vila Euclídes soccer field, in which the union board invites the workers to resume work and negotiations with the bosses. The film begins with the image of police officers patrolling the streets on horseback, a recurring image in the documentary that seeks to tension images of the popular struggle with records of state repression forces - a stylistic trait that we find in other works of the program. A notable formal aspect of the film is the adoption of a documentary writing that refers to the “sociological model of documentary” identified by Jean-Claude Bernardet in his analysis of some Brazilian documentaries. It is a textual organization that uses the voices of popular workers as “voices of experience” which, in the film, are articulated by the documentarist's “voice of knowledge” in a relationship of obvious asymmetry. In the end, it is the documentarian's voice that tells us the story, using the experiences collected to affirm his theses about the events. Despite this, the film makes an effort to record and contextualize the struggles of workers in that emblematic year for Brazilian history. We find in this documentary, therefore, a Brazil that is pressing for the end of the military dictatorship in a gesture that shows a strong desire for the democratic opening of the country.

Another work by Batista de Andrade, Trabalhadores - Presente! (1979) takes a dive into the celebrations of May 1, 1979, Labor Day. Following a tradition invented by the populist regime of Getúlio Vargas, the military government held an official commemoration of this national holiday at Pacaembu Stadium in São Paulo. Faced with this ghostly performance that celebrated a false union between capital, labor and the dictatorship, the workers led by Lula's union group produced an independent celebration that confronted the official party. The film begins in the hubbub of a fair full of workers. The montage entangles interviews with the camera wandering through the face of the popular fair: we walk among faces, labor gestures, food being prepared and sold.

A mixture of party and fury appears on the scene. The workers' struggle emerges to the sound of an accelerated samba. Our blood heats up before the people who rise up to claim their rights and celebrate. The filmmaker's voice contextualizes the images: we are in the first independent commemoration of Labor Day in 15 years of civil-military dictatorship. The location is the emblematic Vila Euclides Stadium in ABC Paulista, where workers started to meet after the interventions in the metalworkers' union. The workers managed to carry out the celebration with the help of civil-democratic organizations that gained strength in the final years of the dictatorial regime. It is important to note that the film not only seeks to draw a panoramic portrait of the event, but also pays attention to everyday movements, misunderstandings, small conflicts, discussions, the backstage of social organization. The documentary ends with the recording of a beautiful speech by Lula that serves as a glimpse of the democratic opening to come.

Greve de Março (1979) is a film by collective authorship that strongly represents the desire for intervention, participation and engagement of the filmography of the cycle of metalworkers' strikes. The film's first images are photographs of police officers patrolling the city. The montage confronts the images of police forces with photos of striking workers in action. The voice of a worker narrates the facts: “The strike was not declared by the workers. It was decreed by the intransigence of the employer class who only want to exploit the workers. When it comes time to give a raise, they don't even want to talk. Their business is to talk to the idle machines”. Drums begin to beat in friction with the images of the police repressing the workers in a march, a gesture that sets the pace of the confrontation between the State and the people. Like other works in this program, the writing of Greve de Março follows a dialectical orientation - a film woven under the sign of confrontation that seems to mimic the social tensions it sought to record.

This work therefore narrates the events of the March 1979 strike from the perspective of the working class, which, in the film, is represented by testimonies of workers and Lula's speeches during the period of strikes. The end of the work shows a public speech by Lula at the ABC Stadium after his release, a scene that was widely recorded by documentaries of the time. In his speech, the future president of Brazil asks that workers return to work so that negotiations with the employer class can continue without, however, lowering workers' morale. Lula and his board promise that if the movement's demands are not met, a new strike will begin. The discursive ability of the political leader is widened by the immediate success of his performance. To our astonishment, the proposal was almost unanimously accepted by the more than 100,000 workers gathered in the assembly. One of the most vigorous expressions of Lula's political capital in this period is, without a doubt, the images of workers' hands in the air and clenched fists in acceptance of the proposal by the directors of the São Bernardo do Campo metalworkers' union that we see in this and other films from the program.

The film ends with the leader of the workers being lifted on the shoulders of the crowd that shouts: “United workers, you will never be defeated!”, one of the great war cries of a generation that rebelled against the tyranny of world capitalism that, as we know, has always grown up under the tutelage of dictatorships more or less masquerading as democracies.

Like other works in this program, ABC Brasil (1980), by José Carlos Asbeg, Luíz Arnaldo Camps, and Sérgio Péo, is a libertarian short film in its shape - but there is an anarchic movement here that escapes the other films presented in this mosaic. The documentary experiences a sensorial immersion in the assembly that closes the previous film. We have to admit that this is a gem of a Brazilian short film, both for its stylistic aspects and for the institutions involved in its production. About the first reason, I highlight its plastic beauty, its artisanal montage that looks more like a surrealist collage and the choreography of the furious bodies that its mise en scène rehearses. Produced by the Brazilian Association of Documentarists and Short Filmmakers (ABD) and the Cooperative of Autonomous Filmmakers (CORCINA), the film begins in an incendiary way with reddish images punctuated by a guitar solo by Jimmy Hendrix that, combined in an unsuspected experiment, ignite our senses - a frantic agitation takes over the bodies of the spectators, who feel the need to dance in front of the camera. A close-up on a photograph shows one of the marches of furious-looking workers that erupted in the 1979s. Hands up and mouths open - the gesture and the scream. Zooming out reveals the breadth of the event: a crowd fills the city streets.

It would be wrong to assume that this is another film about one of Lula's most famous speeches during the general strike of metallurgical workers in 1979. Like other works by the brilliant filmmaker Sérgio Péo, ABC Brasil is an acrobatic film. We find a mise en scène that manages to wander through the landscape of the labor union meeting through very well-paced zooms and panoramics, interrupting our enjoyment to report the unfolding of the metallurgists' struggle through voice and still images. The ending intensifies the sound experiment taken on by the filmmakers: Lula is released from jail and returns to Vila Euclides Stadium. To the sound of Forró do ABC, by Moraes Moreira, we see the union leader being received with hugs, tears and war cries. The fight goes on. That's the lesson of ABC.

In A Luta do Povo (1980), Renato Tapajós, in alliance with the Popular Health Association (APS), shows us the intertwining of different popular movements in the 1970s. The singularity of this film resides in this panoramic record that reveals the connections between social agendas and popular struggle movements in São Paulo and its periphery. The work begins with a card in red fonts against a black background that informs us of an insipid occurrence: the murder of the metallurgist Santo Dias da Silva by the police during the salary campaign of the strike movement in São Paulo's ABC region. The narrator's voice reads the writing to the sound of a police siren. We see the threshold of the Sé Cathedral, in downtown São Paulo. A vertical camera movement shows the mourning workers during the funeral rites of the cowardly murdered workers' leadership. We follow the procession and the camera focuses on the worker's widow. Her lament quickly becomes a battle cry chanted by the crowd: “The fight continues!”. The scene is revealing, as it shows us a characteristic passage of popular struggles around the world. It is precisely loss and mourning that catapult popular uprisings. The collective wail quickly turned to a gesture of fury.

The narrator not only contextualizes the events, but also provokes reflections, raises questions around the nation's social problems and condemns the system of oppression that plagues the poor in Brazil. He is not a neutral narrator, but a historical subject implicated in the historical situation. The narrator of the work is, therefore, a character who takes a position in the face of events and seeks urgent answers from society in the voices of the workers.

The workers condemn the capitalist exploitation of work, the labor legislation that does not protect them, and a series of problems that do not only concern the country's dictatorial government system, but above all concern the plots of international capitalists who profit through global exploitation schemes. The awareness of the transnational procedures that sustain the precarious working conditions of metallurgical workers are clearly and intelligently exposed by one of the workers interviewed by Tapajós, one of the protagonists of the strike movement that reappears in other works of the program, called Osvaldo.

Linha de montagem (1982) makes a kind of historical and critical assessment of the strike movement of the years 1978-1980 through the voice of its protagonists. An interview with Lula structures the navigation carried out by the film through a labyrinth of memories of the great strikes. Other key figures of the trade union movement are interviewed in order to contextualize the period of confrontations of the labor movement in the late 1970s and its impacts on Brazilian society. It is a communicative and pedagogical work that builds a crucial historical narrative to understand the social tensions of the past from the point of view of the oppressed and, also, to think about solutions for the current challenges of Brazilian society.

Santo e Jesus, Metalúrgicos (1983), by Cláudio Kahns & Antonio Paulo Ferraz is, without a doubt, the greatest masterpiece of the period. In stylistic terms, the film presents a unique textual organization by confronting characters and voices in a markedly dialectical texture. Of course, this is not the only film that presents confrontation as a form organizing facts, but this is the work that best incorporated the contradictory character of the social process recorded and narrated by filmmakers engaged in the struggle of São Paulo workers. The duo of documentary filmmakers takes two emblematic characters of the trade union movement and their respective murders as a means of not only showing, but also critically understanding the great São Paulo strikes in all their complexity. To this end, the film ventures into the interpellation of enemies, that is, the killers of workers and their surroundings: companies, bosses, the police and, finally, the government. The dialectical montage confronts the enemy's point of view with images of the workers' struggle. One of the main reasons for the brilliance of this film resides in the fact that Santo e Jesus, Metalúrgicos is a work resulting from a radical gesture of observation, provocation and carnivalized disavowal of those in power. By turning their cameras with special dexterity towards the businessmen and their talkative lawyers, the brutal police officers and their absurd lies, these documentarians produced rare images that served, on the editing table, as building material for a film that rubs violently and, at times, ironically, the apparitions of the executioners and the resistance figures. If all the films included in this program show, each in their own way, the movement of social movements, Santo e Jesus, Metalúrgicos is, without a doubt, the work that perfectly hits the rhythm of this movement: the rhythm of death and mourning converted into fury.

Finally, we come to the most studied and remembered work of the 1979-1980 strike period: ABC da Greve (1990), by Leon Hirszman. This is a curious film, as it was made in two moments. The documentary was shot between the months of March and May of 1979, but was only finished three years after the director's death. This was only possible thanks to the initiative of photographer Adrian Cooper, who assembled the raw material left over from the filming. The work is therefore a complex configuration and composite authorship, even though Cooper tried to faithfully follow Hirszman's intentions. Another important aspect of the production method of the work is its filming was an experiment for the research of another work, the fictional drama Eles não usam black-tie (1981), adaptation of the homonymous play by Gianfrancesco Guarnieri, from Teatro de Arena. ABC da Greve follows the strike movement with special attention to the figure of Lula in a panoramic style that does not fail to show scenes in which the director, like a researcher, challenges representatives of the opposite pole of the labor conflict. The film moves between assemblies, factories, protests, negotiations, leafleting in the neighborhoods and other activities in a fragmentary way, assembling a true mosaic of the memory of the strikes with attention to the backstage and the residues of the most emblematic scenes. This is, without a doubt, a monumental work that narrates the epic of the metallurgical workers of ABC Paulista in the late 1970s.

Faced with these precious images, skepticism overtakes us: what to do with these images from the past at a time when work and workers are in a violent crisis? But hasn't the world completely changed, so that it would be impossible to identify similarities between these reminiscences and our current situation? The Brazilian cinema of the last 20 years, with important exceptions such as films by Affonso Uchôa, Adirley Queirós, Juliana Rojas, Marco Dutra, Dácia Ibiapina, Renan Rovida and others, has relegated the worker to oblivion, although the current moment shows us signs of renewal in the figuration of the new modalities of the urban proletariat. Be that as it may, it is a known fact that the worker has become a phantom character in politics and culture. One way to think creatively about these images is to use them in our present of new aspirations, challenges and dangers. Is it possible to point out new paths from this montage between the past and the present? What do these stories of factory workers in the past tell us about the world of today's delivery men and street drivers? Without aiming to answer complex questions in a short essay, I can only say that the world of the contemporary urban precariat is indeed radically different from the universe of the shop floor, but the updated forms of exploitation carry survival of the oppressions of yore and, notably, the strike remains one of the main tactics of the workers' war.

It is important to remember that the working class and Lula, its main leader, emerged on the board of Brazilian politics and culture during the crisis of the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship, and Jair Messias Bolsonaro gained power and assumed the Presidency of the Republic in the crisis of representative democracy that began in 2013. We can conclude that what is in dispute today in Brazil is the construction of a new political body from the guts of our current catastrophe: the world of the precariat. From the bowels of the world of workers without rights, sparks of hope for a new social transformation can emerge. Articulating the images of the metalworkers' strikes and the rise of the working class as a character in a context of intensifying the economic, social and cultural contradictions of this sad Republic is, after all, to raise questions, provoke provocations and open our eyes to the improbable, the invisible. If an uprising does not take place without chants, we must look carefully at the ruins of capitalism and this “brave new world” that has been configured in recent decades in order to then sing of another possible world. It is not by chance that the main current trends of Brazilian independent cinema have produced works that make this dystopian world strange from opposite poles, but which, today we know, can converge in explosive experiments: documentary and speculative fiction - cinema “under the risk of the real” and the fanciful fables that radicalize the contradictions of the present. Be that as it may, the films made during the metalworkers' strikes represent a period not only of intense stylistic experimentation in national documentary filmmaking, but also a true political aesthetic laboratory in which an aesthetic of the scream was germinated in alliance with the oppressed. These films taught us that a cinema in friction with the world is a fertile way to combine stylistic experimentation with political intervention.