There are films which capture the true spirit of big cities beyond the stereotypical images that can be found in tourism ads. In the case of Rio de Janeiro, it is particularly difficult to break away from the mythical land which, for decades, had André Filho’s carnaval march Cidade Maravilhosa as its unofficial (and now official) anthem. The iconography of Rio de Janeiro, relying on immediately recognizable tourist attractions such as Christ the Redeemer and Sugarloaf Mountain, has been reproduced in interior sets for the black-and-white musical comedies known as chanchadas; its avenues, squares and five-star hotels have been avidly exploited in gorgeous Hollywood technicolor, and it has been personified, internationally, by “ambassadors” as great as Carmen Miranda and Antônio Carlos Jobim. Such is the Rio which is sold for Brazil and the whole world, but anyone truly willing to find out what is behind the façade knows that ever since the samba is the samba,1 there has always been more.

When Orson Welles was exported to Rio by the American “Good Neighborhood policy” to film the carnaval and embed it in his documentary project “It’s All True”,2 his chaperone from the local financial elite was poet and diplomat Vinicus de Moraes. But during his trip it was actor Grande Otelo3 who struck him the most. Otelo took him up the hills to find “the real Rio”, that of the black and mestizo people who might be bohemians but are always hard-working, the Rio of marginalized populations who are the true authors of popular festivities, which official powers are always trying to tame and claim for themselves. Welles found out that the people of Rio de Janeiro (and the real Carnaval, organized by them) was far beyond the color footage he shot at the Cinédia studios.

According to records we now have access to, we can say the closest that “real Rio” had ever come of being portrayed by Brazilian cinema until then was in veteran director Humberto Mauro’s 1935 Favela dos meus amores (considered a lost film). More than a decade after the director of Citizen Kane was in Brazil, Nelson Pereira dos Santos would expose the social and urban contrasts of the “cidade maravilhosa” in his 1955 Rio, 40 Graus - which broke so much new ground that it was subjected to censorship by the Rio de Janeiro state police. The film was only allowed exhibition after an intense campaign in its favor by the intelligentsia and the press. In many ways, Nossa Escola de Samba, a 28-minute 1965 film directed and edited by Manuel Horácio Gimenez, is one more step in the path taken by Humberto Mauro, Orson Welles, and Nelson Pereira dos Santos. In many ways, the film even surpasses them, as it benefitted from a key aspect of the zeitgeist of 1960s Brazilian cinema: social documentaries.

That approach is one of the foundations of the first phase of Cinema Novo, although it is not limited to that movement. Social documentaries were being made by both auteurs and artisans (according to the categories utilized by Glauber Rocha).4 To summarize, we can cite 1960s Brazilian social documentaries films such as Linduarte Noronha’s Aruanda (1960), Paulo Cezar Saraceni’s Arraial do Cabo (1960), Geraldo Sarno’s Viramundo (1965), Glauber Rocha’s Maranhão 66 (1966) and Arnaldo Jabor’s A Opinião Pública (1967). Even fictional films (affiliated to Cinema Novo or otherwise), such as the anthology Cinco Vezes Favela (1962), produced by Centro Popular de Cultura da União Nacional dos Estudantes, or the Swedish-Brazilian co-production Mitt hem är Copacabana (1965), are clearly influenced by social documentaries, although they are also deeply influenced by the fictional Rio, 40 Graus (which may itself be responsible for some tendencies of the social documentaries of the 1960s).

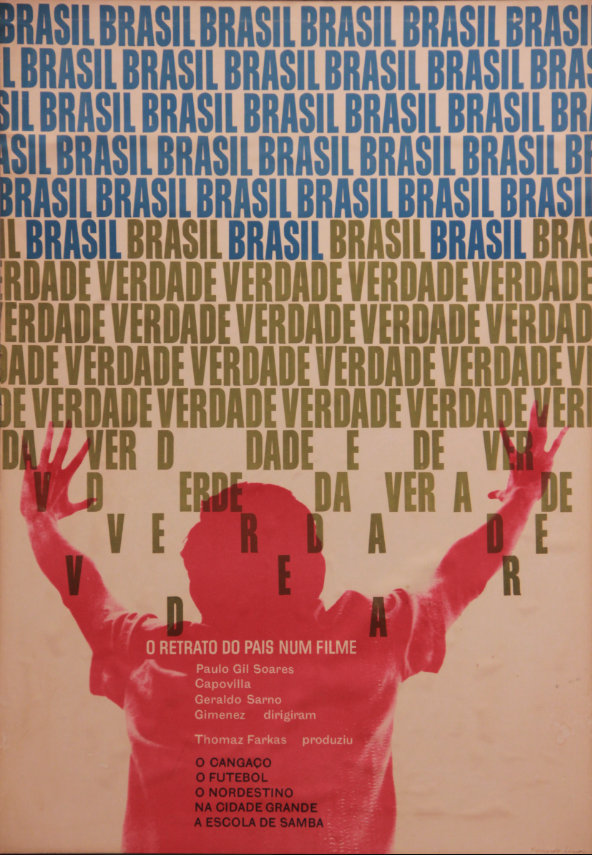

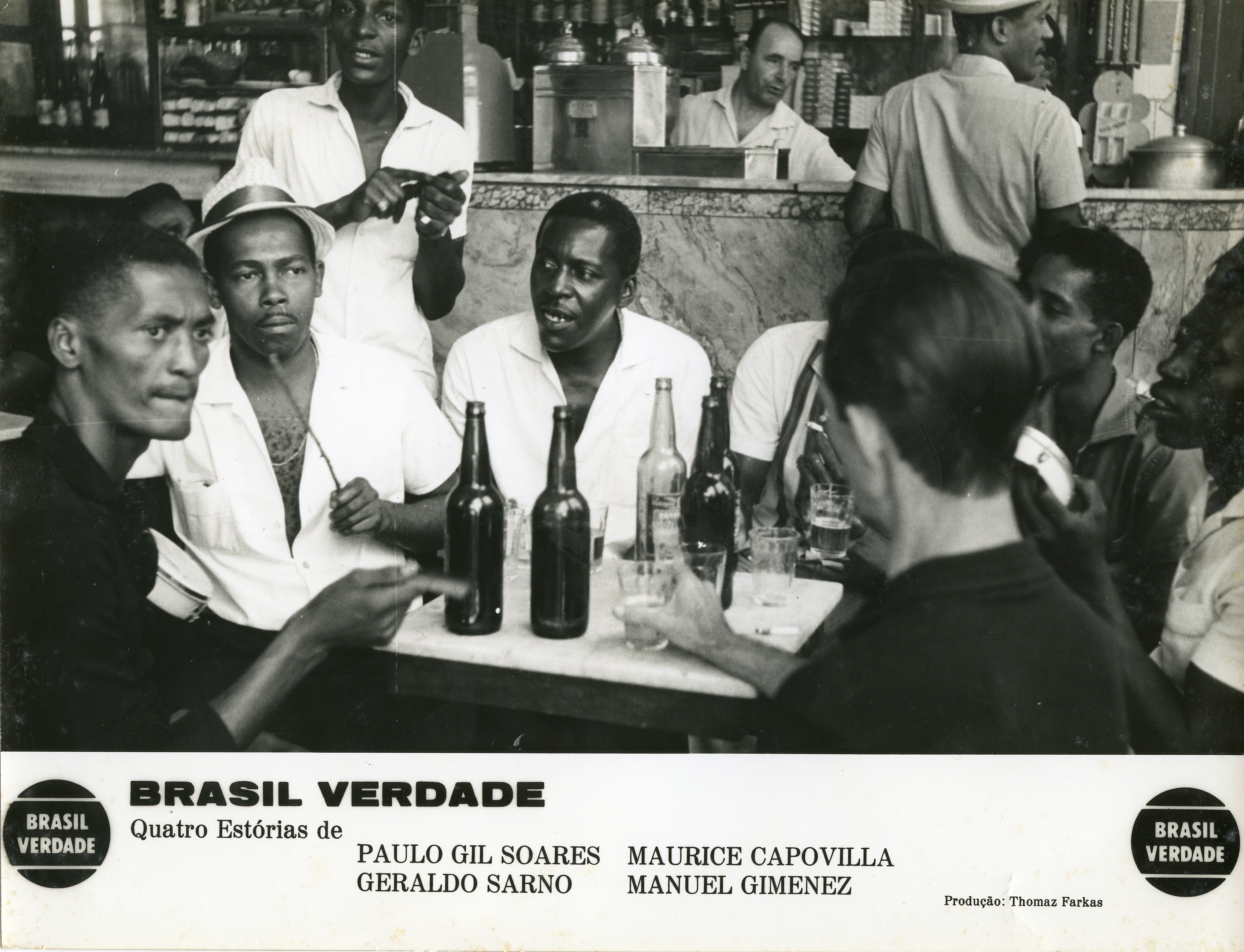

Nossa Escola de Samba, however, is closer to 1960s social documentaries. The key figure behind the film is Thomaz Farkas, a man who played a fundamental role in the development of Brazilian social documentaries and the history of Brazilian cinema. As a cinematographer, producer and director, the Hungarian-Brazilian filmmaker built an extensive filmography and was responsible for the anthology film Brasil Verdade (1968) - which cobbled together short films produced by him and was made thanks to his efforts to import equipment that could record direct sound. Up until then, most Brazilian films were dubbed in studios, and the new possibility of direct sound recording allowed for certain projects to change paradigms, among which documentaries evidently benefitted the most.

Nossa Escola de Samba is among the shorts selected to integrate Thomaz Farkas’ Brasil Verdade, and it relates to the other episodes of the anthology (Memória do Cangaço, Subterrâneos do Futebol and Viramundo) because all of the shorts discuss political, social and cultural aspects of Brazil at the time following the 1964 military coup. Originally shot on 16mm, the shorts were blown up to 35mm for the feature film.

There is little information regarding Manuel Horácio Gimenez, the Argentinian chosen by Farkas to direct Nossa Escola de Samba. His previous credits include co-writer or second unit director in Argentinian films such as Tiré Dié (1958), La primera fundación de Buenos Aires (1959) and Los Inundados (1962), all directed by Fernando Birri. Nossa Escola de Samba (and, by extension, Brasil Verdade) is seemingly his only significant contribution to Brazilian cinema. An Argentinian filmmaker heading a documentary about the Carnaval in Rio de Janeiro might seem like an unusual choice, but, even with the potential for Nossa Escola de Samba to result in something coldly seen from afar due to the geographical barrier, the final product is exactly the opposite. While the distant point of view may be there, it is not cold in the slightest: Gimenez wanders through the environment with free eyes and eager to understand the Carnaval universe, paying attention to details which a Brazilian filmmaker might ignore due to a relative familiarity with Carnaval.

The short film follows the year-long preparation for the Carnaval parade of the Grêmio Recreativo Escola de Samba Unidos de Vila Isabel, and is structured around interviews with Antônio Fernandes da Silveira, a.k.a. “China”, one of the founding members of that group (he also appears in the film, and his speech works as an off-screen narration throughout). Gimenez’s camera enters the daily lives of those living on the Pau da Bandeira hill, home to the members of Escola Vila Isabel, and it investigates the life of a certain social stratus in Brazil, taking that community as a microcosm and focusing on how their routines change while preparing for the carnaval. The Argentinian filmmaker summarizes this by saying "in the film, we get a glimpse of life in a favela and how it transforms as the Carnaval approaches. We follow Vila Isabel’s Carnaval parade in richness of detail, then the film ends with its members going back to their daily jobs once the party is over. The image and direct sound were able to capture the characters naturally in their daily environment, and with their authentic musical expression."5

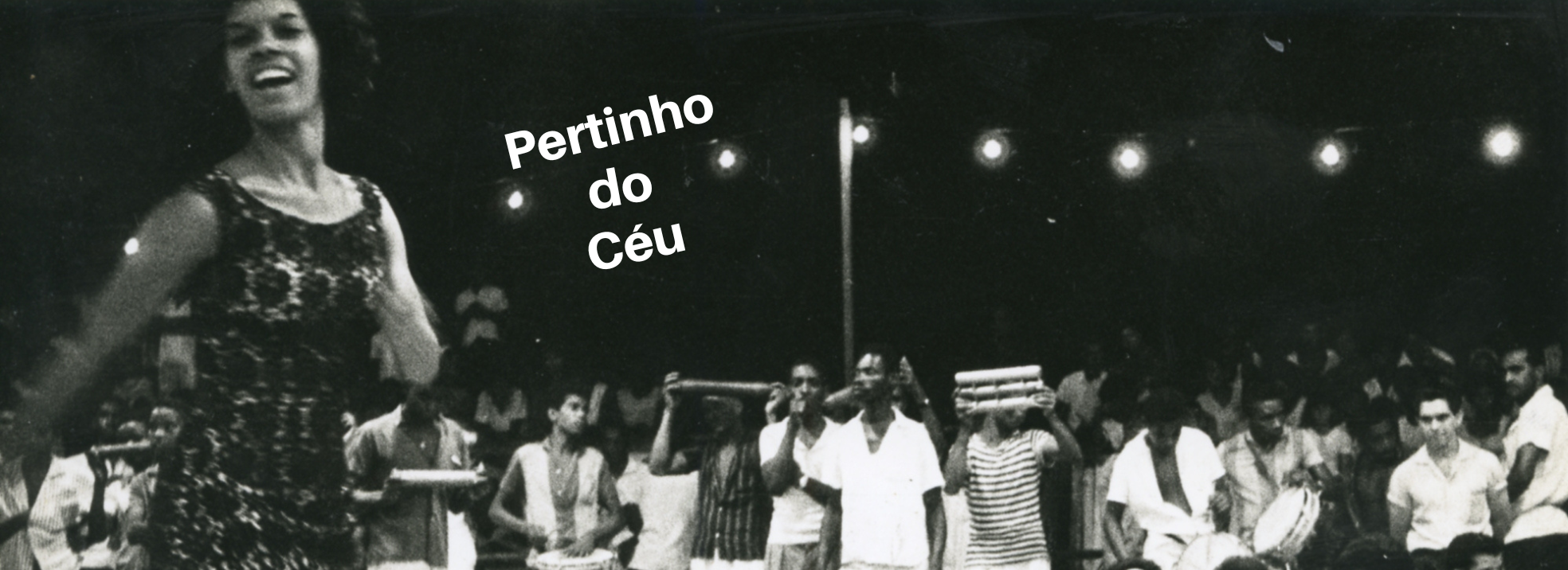

“Florinda is our flag-bearer”, says “China”, off-screen, as we watch the first rehearsal, “she works in a cloth factory. And the other members are mostly bricklayers, electricians, cleaning women; there’s also a driver; and many are painters. Even Ana Lúcia - Suco’s youngest daughter - is thinking of finding a job. Suco is a mechanic, and he comes by every morning to call me so we can walk together to where we work.” In the first moments of the film, the images (showing the vivid rehearsal at the Municipal Theater) aligned with the sound (of the samba-enredo chosen by the Escola) present the contrast between professional life and daily life for those people, in a moment when their daily toil is suspended to give way for Carnaval work.

The popular celebration is made possible when a collective force, uniting every sector, comes together to reach a common goal (according to 'China', “once the rehearsals start, samba is like a microbe to us”). Preparation starts in October, six months prior to Carnaval, when rehearsing for the parade begins in the local sports court. However, the locals are never portrayed as amorphous or homogeneous. To exemplify the diversity of the organization, we can point to the scene where China explains that, “most of the members come from uphill [the favelas], because they’re more skilled, they’re more familiar with samba; Black people have got samba in their blood, it is theirs, but some white folk are a decent match”.

Gimenez takes an opportunity, amidst irresistible imagery of the collective aspects of the Carnaval rehearsals, to focus on little individual tender moments: while China names the professional activities of the people rehearsing, a shot of Suco’s daughter dancing and singing, followed by her father watching her with affection.

Such logic - of juxtaposing individual and collective aspects - is established organically, and the whole film is based on it; Gimenez wants to show us the daily lives of the dwellers of the Pau da Bandeira hill, instead of focusing exclusively on matters of the Carnaval. As we witness a morning in the favela, we are shown problems faced by those who live there, such as water shortage. But the film also takes its time to portray tender images of children eating at the table. Gimenez’s gaze, genuinely curious and affectionate, is closer to Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Rio, 40 Graus, than, for instance, the later wave of favela movies made during and following the Retomada,6 with their “cosmetics of hunger”,7 which saw the favelas as little more than a background for stylized exploitation films.

Even when the focus is, strictly speaking, on preparation for the Carnaval parade, Nossa Escola de Samba makes a point of following up the rehearsals with what happens after they are over: the workers relax, have a beer, smoke a cigarette, chat; street vendors walk around, couples date, neighbors gossip, the musicians stroll around in suits and starched shirts, and China explains the various fundraising fronts undertaken by the School to make its Carnaval financially viable.

Gimenez follows the preparations in a chronological manner: the first rehearsals, the trips to the Theatro Municipal to settle issues of a more bureaucratic nature, the construction of the floats in the sheds, the handmade molding of clay figures, the delegation of responsibilities, the preparation of the costumes by the seamstresses, and the painting of the scenery. The closer Carnaval is, the more China’s words are proven to be true, when he referred to the celebration as a "microbe" which infects everyone in the Pau da Bandeira hill. When the film announces that the parade is two months away, we hear drums beating, which the audience might mistake for that of a drum in the previous sequences which show the rehearsals in the sports court. However, it is soon revealed that the drum beating is completely spontaneous: in a courtyard between the houses, residents drum on tambourines or even on paint cans; they sing in chorus, in a circle in the center of which men, women, and children join in the dance. In a bar at the foot of the hill (which Gimenez explores in richness of detail), the song chosen by the people as their favorite is sung and rocked by triangles, beats on wood or matchboxes - which are traditional samba instruments. In a very natural and noteworthy shift, the song transitions to a choir of female voices, as we leave the bar and return to the general rehearsals.

Nearly as quintessential as the final parade is the moment that precedes it, as the dwellers of Pau da Bandeira hill conquer the asphalt and go to downtown Rio to join the street blocos8 with such enthusiasm that, in just a few minutes, they synthesize what is true and popular in the carnival of the blocos. The final parade, despite the different location and the costumes, differs little from the rehearsals: the mood is the same. This, for the film, allows us to understand that the rehearsals and the parade are equally important. Nossa Escola de Samba features a Carnaval from a different time, when parades were held in downtown Rio, for all to see: the Marquês de Sapucaí Sambodrome, their current location, was built decades later, in 1984. Once the parade is over, China says, noticeably proud, that Unidos de Vila Isabel School finished second in the second tier of the competition, “so now, we and the first place, leave the second tier. Now, we’re going to parade at Presidente Vargas Avenue.9 Next year we’ll be among the greatest: Mangueira, Portela…”.

After their triumph, Pau da Bandeira hill goes back to their daily lives, until next October. Gimenez shows us the following morning: China looks down at the city from his window. Off-screen people (the direct sound, made possible by the modern equipment imported by Thomaz Farkas, attentively records that favela’s soundscape) sing Zé Keti’s10 samba Opinião (“fale de mim quem quiser falar / aqui eu não pago aluguel / e se eu morrer amanhã, seu doutor / estou pertinho do céu”11). Somewhere in the distance, dogs bark. Boys in uniforms walk to school; the mother of Ana Lúcia (Suco’s daughter), highlighted in the first rehearsal, wakes her daughter up. Suco drinks coffee as he watches people go by. The people go on singing Opinião (“Podem me prender / podem me bater / podem até deixar-me sem comer / que eu não mudo de opinião / daqui do morro, eu não saio não”12). Men and women go downhill to work and earn their daily bread. The chorus of Opinião goes on, until the voices fade out. The sun goes up as another day begins. Pau da Bandeira hill is pure samba, even if Carnaval is over. Or maybe samba is pure Pau da Bandeira hill. The people are inseparable from their party, Carnaval, as they are the main component of the very DNA of Carnaval; without the people, it simply doesn’t happen. Nossa Escola de Samba is an underrated gem of Brazilian cinema and one of the definitive films on one of the greatest events on the planet.

1. Reference to a Caetano Veloso song. Meaning “always”.

2. Unfinished film partially shot in Mexico and Brazil by Orson Welles. An RKO production, It’s All True was canceled due to problems such as the accidental death of a fisherman who starred in one of the film’s episodes, and the interference of Getúlio Vargas’ administration via the Department of Press and Propaganda. The original negatives were seized by RKO and considered lost for decades, until part of them was found and edited into a 1993 documentary about the project also named It’s All True (Wilson, Krohn & Meisel, 1993).

3. See CABRAL, Sergio: Grande Otelo, uma biografia. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2007, p. 83-93.

4. See ROCHA, Glauber: Revisão Crítica do Cinema Brasileiro. SãoPaulo: Cosac & Naify, 2003.

5. From a quote attributed to Gimenez on a poster of the film. Digitally reproduced here: <thomazfarkas.com/filmes/nossa-escola-de-samba>.

6. “Retomada” refers to the period in the 1990s when, via grants and new culture incentive laws, Brazilian cinema resumed a steady production rhythm after years of scarcity caused by the dissolution of Embrafilme, the mixed funding state-owned film production and distribution company founded in 1969 by the military government in a partnership with Cinema Novo filmmakers, and dissolved in 1990. Carlota Joaquina, the Princess of Brazil (Carla Camurati, 1995) is regarded as the starting point of the Retomada era. “Post-Retomada” loosely refers to the 2000s, with significant landmarks such as Amarelo Manga (Cláudio Asssis, 2002) and Cidade Baixa (Sérgio Machado, 2005).

7. The term “cosmetics of hunger” was coined by researcher Ivana Bentes, as the antithesis to Glauber Rocha’s aesthetics of hunger, and popularized by critic Cleber Eduardo when he reviewed City of God (Fernando Meirelles e Kátia Lund, 2002) for Época Magazine.

8. Informal groups that dance and party in the streets during Carnaval.

9. The main street of downtown Rio de Janeiro.

10. José Flores de Jesus, better known as Zé Kéti, was among the most important samba composers in history. He was a member of Portela samba school. His songs were recorded by bossa nova singer Nara Leão, and they served as the basis for the 1964 theater play Opinião - one of the early landmarks of cultural opposition to the military dictatorship. An orchestral rendition of his song A Voz do Morro was the opening theme of Rio, 40 Graus (1955), directed by his friend Nelson Pereira dos Santos. He appeared in other Cinema Novo films such as Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Boca de Ouro (1963) and Paulo Cézar Saraceni’s O Desafio (1965). After his death in 1999, Nelson Pereira dos Santos made a short film as a tribute to him, Meu Compadre Zé Keti (2000).

11. “Let they talk about me/ Here I pay no rent/ And if I die tomorrow, mister/ I’m so close to heaven already”

12. They can arrest me/ They can beat me up/ They can even starve me/ I won’t change my opinion/ I won’t leave the favela”