In Brazil, the 1930s arrived driven by the excitement for sound cinema. This technological innovation quickly transformed the landscape of film production in the country and brought about a transition period for the national film industry. During the transition to sound cinema, aspects such as subtitling and dubbing, increased production costs, and the technological adaptation of theaters, resulted - albeit temporarily - in the reduced presence of American films in the national market.

This conjuncture, in addition to the desire of developing a stronger national film industry, inspired Brazilian productions to adapt to the molds of Hollywood studio productions. Taking elements from musicals (a successful genre exported worldwide), films such as Alô, Alô, Brasil! (1935), directed by Wallace Downey,1 was responsible for bringing together popular figures such as Carmen Miranda, Ary Barroso, Sílvio Caldas, Francisco Alves and Mário Reis. Musicals such as Alô, Alô, Brasil! provided audiences with a new kind of connection with radio superstars, as they could finally be seen on the big screen. Thus, carnival comedies began to evolve, betting on what is familiar and popular among Brazilians: language and music.

Publications such as the Rio de Janeiro-based Cinearte magazine played a key role in offering legitimacy to the hegemonic classical Hollywood cinema and the star system, a mechanism created by the film industry to manufacture the ideal beauty essential to stardom. In order to establish standards and references of beauty, skills and techniques were improved in make-up, production, hairstyle, costumes, photography and even plastic surgery was used to remove physical imperfections. Thus, care and selectivity were applied to what would be shown in the movies. The highlight would then be the achievements, natural features, beauty, elegance, and the photogenic nature of a people who were, almost without exception, white.

In this sense, Barro Humano (1929), directed by Adhemar Gonzaga, stands as a symbolic film. Marked by luxury, pomp, and sumptuous locations, the work became an opportune showcase for the launch of new stars and the consecration of those already established. The notoriety achieved by the production, both commercially and artistically, propelled the founding of Cinédia in 1930, which would go on, over the course of two decades, to deliver to audiences the most iconic chanchadas² in Brazilian cinema.

The studio’s first ventures were Lábios Sem Beijos (1930), the Rio de Janeiro debut of Minas Gerais–born filmmaker Humberto Mauro, followed by Mulher (1931) and Ganga Bruta (1933). Considered Cinédia’s first carnival film, A Voz do Carnaval (1933) marked Carmen Miranda’s second appearance on screen.

By combining musical numbers with comedy, romance, and suspense, Gonzaga—the creative force behind the studio—helped shape a distinctive genre. His business acumen and keen awareness of the market kept the company highly profitable. These productions, typically made with limited financial investment, relied on stage adaptations with proven success, popular radio stars in the cast, and carnival films released at strategically chosen moments of the year, thus ensuring minimal risk.

At the time, the Getúlio Vargas government made great efforts to create a modern and positivist image of the country. Cinema emerged as a powerful tool for the government to support their nationalist project. State intervention in cinematographic activity led to the creation of the INCE (National Institute of Educational Cinema) in 1936. That decade was marked by the demand for protectionist laws; however, it was only in 1939 that the obligatory exhibition of one Brazilian feature film per year was established.

At the beginning of the following decade, Moacyr Fenelon and the brothers Paulo and José Carlos Burle founded Atlântida Empresa Cinematográfica do Brasil S.A in Rio de Janeiro with the support of Count Pereira Carneiro, owner of Jornal do Brasil. Although their main product was carnival comedies, the founders of Atlântida saw cinema as a tool for artistic education and often produced films with a critical-social approach. Such is the case of Moleque Tião (Burle, 1943), which, by telling the story of Grande Otelo's life, openly discussed racism in a drama with a neorealistic tone.

Although, in practice, his influence was not strong enough to oppose the influence of Hollywood on the film industry in Brazil, Burle was openly opposed to its hegemony. Carnaval Atlântida (1952) was one of such occasions when parody stood out to ridicule the extravagance of the historical epics, so symbolic of the North-American studio system.

In 1947, Luiz Severiano Ribeiro Júnior took over as director of Atlântida and became the majority shareholder of the company. Defending his interests as an exhibitor, he invested heavily in comedies and provided the public with hits such as Carnaval no Fogo (1949) and Aviso aos Navegantes (1950), both directed by Watson Macedo. With a decree established in 1946 requiring cinemas to show three Brazilian films a year, and the creation of Laboratório Cinegráfica São Luiz, Severiano Ribeiro fully dominated the film industry, making maximum profitability from small investments, small crews, and the use of recycled equipment.

Although these productions were aligned to a popular market, their critical reception was mixed. The exploration of formulas, as well as the links with other areas of the cultural industry, such as radio, theater, circus and the press, helped consolidate the chanchada as a successful genre.

Despite their apparent innocence, these productions did not shy away from criticizing and denouncing class structures, misfortunes, conservatism, and social neglect. As is the case with anything that is exploited to exhaustion, chanchada productions became increasingly rare from the end of the 1950s onwards, with less and less interest from the public. Their burial would come with the death of Atlântida, in 1962.

Born into a large, working-class family, Anselmo Duarte Bento was born in Salto, in the interior of the state of São Paulo. As a child, he sought work as a screen washer³ at the town’s only movie theater in order to watch films for free. When he reached an age at which he began to think about his future, he headed to the capital, a common destination for young people seeking better living conditions for themselves and their families. In São Paulo, he took a few dance classes, which later proved useful when he moved to Rio de Janeiro, where he performed in revue theater.

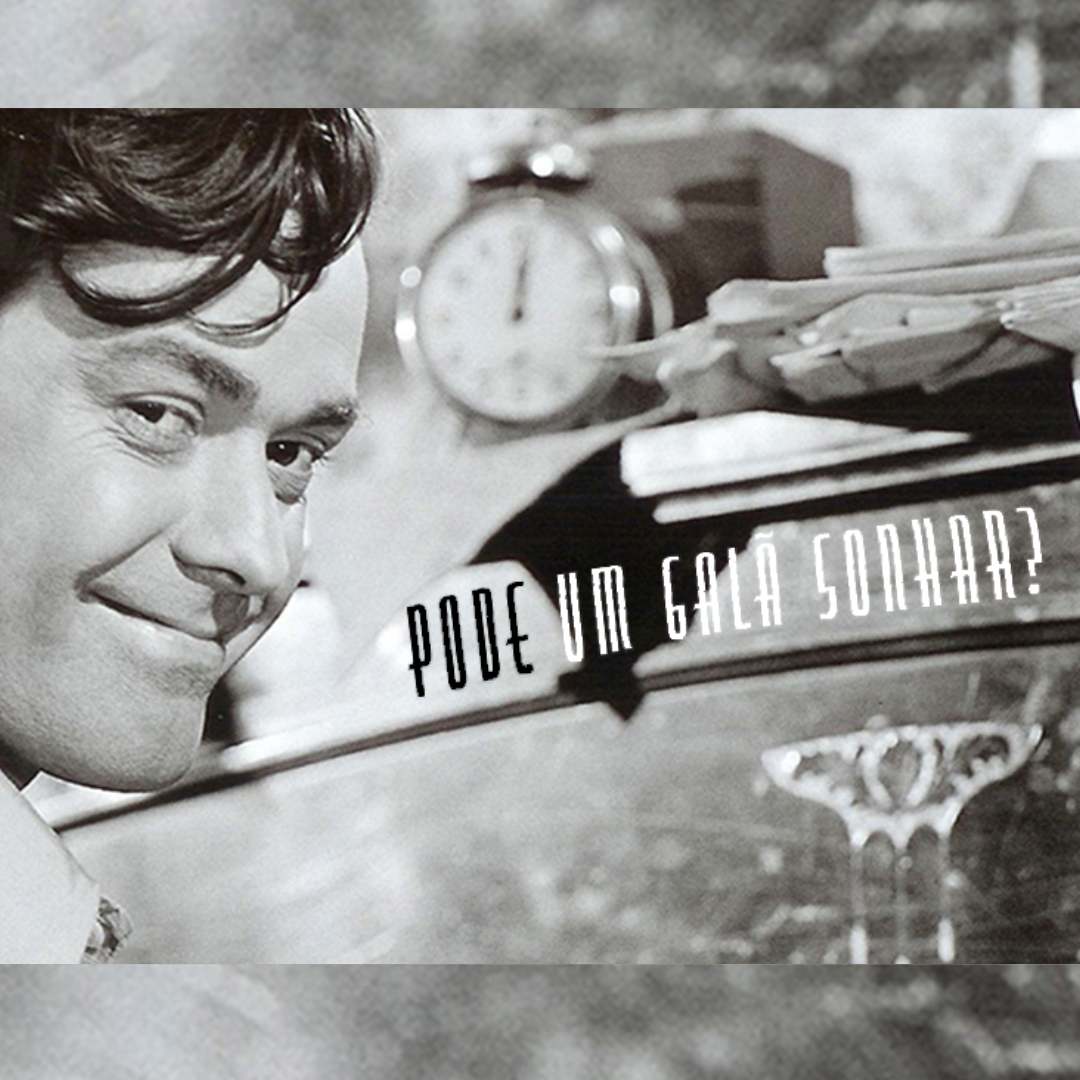

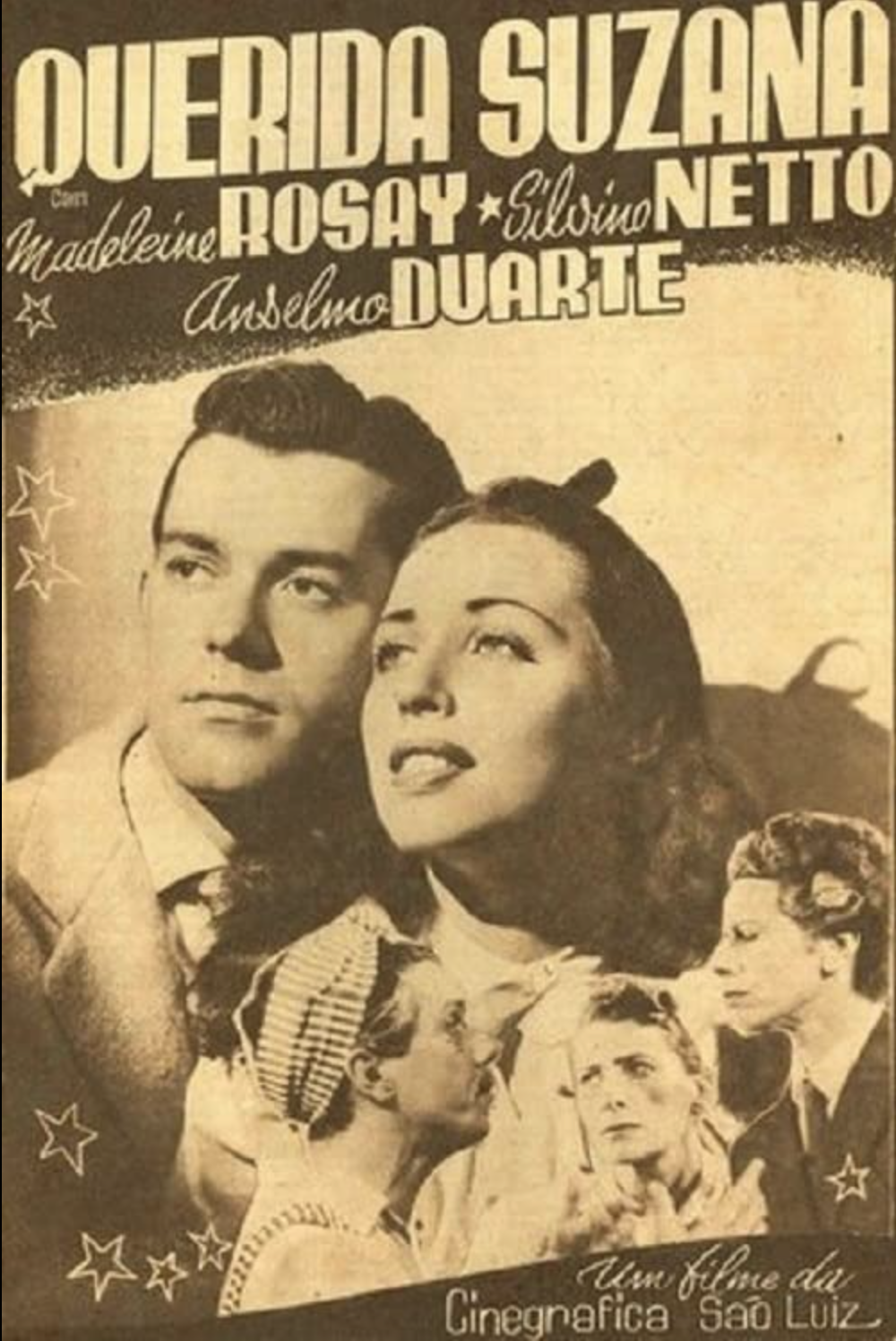

His film debut came alongside Tônia Carrero and Nicette Bruno in Querida Suzana (Pieralisi, 1947), directed by Alberto Pieralisi. Following its success, he began appearing on magazine covers and was courted by emerging studios. Duarte was resistant to the idea of working in carnival comedies, which he regarded as “second-rate,” produced with little technical or aesthetic refinement.

However, in Caçula do Barulho (1949), Italian filmmaker Riccardo Freda went a step further with the dynamics of the genre by adding a surprise element to the already familiar archetypes of the chanchadas: fight scenes. After this experience, Anselmo, who in the film plays a stereotypical good guy, agreed to participate in more chanchada productions. Duarte followed Caçula do Barulho by writing the script for Carnaval no Fogo (1949), a film that marked the studio's new formula for success. The mixture of show business, romance, police intrigue, and comedy of errors, added to the work of legendary photographer Edgar Brasil, and an effective interplay between hero, lady and villain caused the public to easily recognize the cast and their archetypes. Carnaval no Fogo established the iconic romantic couple of Atlântida, Anselmo Duarte and Eliana Macedo, the villain José Lewgoy, and consecrated the comedy duo Oscarito and Grande Otelo. Later, Anselmo would consolidate his image as a national idol in Aviso aos Navegantes (1950).

After a generous offer from Companhia Cinematográfica Vera Cruz, and a series of creative liberties granted, Anselmo Duarte returned to São Paulo to play the role of composer Zequinha de Abreu in the biopic Tico Tico no Fubá (Celi, 1952). Founded by Franco Zampari in 1949, with the support of entrepreneurs such as Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho and the approval of São Paulo's intellectuals, Vera Cruz undertook the construction of huge studios, investing in technical development and in the diversification of genres.

The new company was born, therefore, envisioning a "true cinema", in a São Paulo thirsty for cultural projects compatible with the taste and habits of the wealthier classes who did not go see chanchadas. Vera Cruz set itself against the popularism and vulgarity of the comedies from Rio de Janeiro, and it didn’t take long for critics to look at Brazilian cinema more positively. In light of the emergence of this new powerful studio, the manifesto - film Carnaval Atlântida (1952) is seen as Atlântida's response to the emergence of Vera Cruz. The film reflects the impossibility of making Brazilian films that mirror the ideals practiced by the great North American studios.

With the bankruptcy of Vera Cruz, in 1954, due to factors such as poor financial management, expensive exclusivity contracts, obstacles in the exhibition of films, high production costs, and a closed foreign market, movements arose to solidify the Brazilian film industry. This culminated in the creation of the INC (National Film Institute) and, later, Embrafilme.

Invited by Watson Macedo, Duarte returned to Rio de Janeiro and created a popular film production company at Carmen Santos studios. Carnaval em Marte (Macedo, 1955) and Sinfonia Carioca (Macedo, 1955) were his first films with that studio, both recording satisfactory box-office numbers.

In 1957, invited by Argentinian director Tom Payne, Duarte returned to São Paulo to star in and co-produce Arara Vermelha (1957), shot in the Serra do Mar. Making use of leftover negatives from the breaks in the filming process, and with an Arriflex in hand, Anselmo shot the documentary Fazendo Cinema (1957) about the difficulties faced by the technical crew of a production company with no resources to make a feature film possible. This first solitary exploration into directing was shown as a complement to a program in movie theaters in São Paulo, and won the "State Governor's Award" in the Best Documentary of the year category. For Anselmo, "Awards are worth nothing to those who don't win them. For me it was a great incentive. After the award-winning documentary, I couldn't think of anything else but directing a feature film" (Singh, 1993).

The Last Innocent Man in a São Paulo at the Gates of Modernity

Inspired by a true story of an old man who answered questions about geography on the TV show O Céu é o Limite, Duarte created the character of a young linotype operator, played by himself, who knew the telephone directory of the city of São Paulo by heart. Absolutamente Certo! (1957) was produced with few resources and relied on a cast of first-timers. Famous artists such as Dercy Gonçalves and Odete Lara were in the cast only because they accepted a symbolic payment.

Under pressure to succeed in his debut as a fiction director, Duarte found himself at a crossroads between making an artistic film and a box office hit. Afraid of becoming the director of a single work and fearing commercial failure, he decided to minimize risks and recurred to the experienced technicians remaining from Vera Cruz, such as photographer Chick Fowle. He also included a mix of elements in the film such as musical numbers, rock and roll (which had been forbidden at the balls by the then governor of São Paulo, Jânio Quadros), boxing fights, and judo.

Although industry professionals distrusted Duarte and despite the stereotype of being a simple leading man from Atlântida and Vera Cruz, the critics, who according to Anselmo were "harsh” and "criticized every filmmaker", received the work positively (Singh, 1993). With sold-out sessions in forty movie theaters - twenty in São Paulo and the other half in Rio de Janeiro - Absolutamente Certo! broke audience records.

Absolutamente Certo! retains a rare naivete, just like its character, Zé do Lino. Targeting a wide audience, the film offers comical moments, doses of thrills, music, romance, action, and a range of character-types from the classic villain to the femme fatale.

Absolutamente Certo! is structured in three parts. The main one takes place backstage at a TV station, where we follow the quiz show in which the protagonist participates. In the second, we’re introduced to the world of crime through a boxing academy, which serves as a front for businesses such as corruption of athletes in order to fraud millionaire bets. In the third, we follow the daily lives of ordinary people, the linotype operator Zé, his sick father, and his girlfriend Gina.

As Zé do Lino has the phone book memorized, Raul, the owner of the boxing academy and the brain behind the operations, sees in the young man's talent the possibility of high earnings with the quiz-show. His low salary, the lack of financial resources to marry his girlfriend Gina, and the need to purchase a wheelchair for his father drive Zé do Lino to accept Raul's proposal and apply to participate in the program.

Getting closer and closer to the final game show episode, Raul begins to seduce Zé do Lino with money loans that provide comfort. Raul buys Zé do Lino an automobile and his father's wheelchair, distancing the modest young man from his old working class values. Zé also begins to waver in his commitment to Gina, instead becoming interested in the seductive and experienced Odete (Odete Lara), Raul's lover and TV commercial girl.

Zé do Lino learns of the plan devised by Raul: since everyone expects him to succeed in the last round of the program, Raul would bet a large sum of money on the linotypist's mistake and thus win the whole amount for himself. In order for Raul to get away with this, Zé do Lino would have to make a deliberate mistake. Once aware of the plot in which he was involved, Zé do Lino reconnects with his values and refuses to betray the trust of his father, neighbors, girlfriend and, of course, the viewers who transformed him into an instant celebrity.

Absolutamente Certo! has been described as a kind of "improvement" of the chanchada, "a musical comedy with touches of sentimental drama and satire of manners" (Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras). The natural flow of the dialogues and the rhythm established in the transitions between scenes, with the television set serving as a connector, are also noteworthy. Film critic and theorist Jean-Claude Bernardet writes that in the film, television is not seen as a threat or in a negative way, thus distancing itself from the critical stance that Brazilian cinema would take against the medium in the following decades (Bernadet, 1995).

Bernadet speculates that Anselmo Duarte may not be nostalgic about the loss of tradition, nor does he view the behavioral changes in Brazilian society at the time with euphoria. Rather, he sees TV as "the symbol of the intersection of two confronting worlds" (Ibid.). The imminent progress of society, especially in São Paulo, operates in between the values of the past, such as the unending honesty of Zé do Lino, and the longing of modernity.

Absolutamente Certo! works on the possibility of fusing the most mature Brazilian chanchada with Italian neorealism of a less complex and more sentimental nature, which is evident in the tender representation of the characters of humble origin or the emphasis on union and collective action. There is also the concern to avoid an excessive Manichaeism that puts good before evil.

With the profits made from the film, Anselmo Duarte "takes his face off the screen" and goes to Europe in search of new challenges and knowledge. "[...] I went to the Old World, I went to meet the Nouvelle Vague up close. I went world-wandering" (Singh, 1993, p.68).

What happens after that is the subject for the next conversation in this timely discussion about Anselmo Duarte.

1. Founder of Sonofilmes in 1937.

2. Films characterized by predominantly naive, burlesque, popular humor

3. Editor’s note: Duarte explains what the job was in the book O Homem da Palma de Ouro: "I was a screen wetter. Do you know what that is? Movie theaters in the backlands were so precarious that the films were projected onto a transparent cloth, in front of the spectators. There was only one projector and, while the reels were being changed, in order to prevent the cloth from getting hot and even catching fire, we had to wet the screen with a giant syringe called 'estoloque'."

REFERENCES

ABSOLUTAMENTE Certo!. In: ENCICLOPÉDIA Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural, 2021. Disponível em: <http://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org.br/obra67247/absolutamente-certo>. Acesso em: 21 de Abr. 2021. Verbete da Enciclopédia.

BERNARDET, Jean-Claude. Historiografia clássica do cinema brasileiro: metodologia e pedagogia. São Paulo: Annablume, 1995. CORREIA, Donny. Deus e o Diabo no filme de Anselmo. In: Elipse, n.2. Belo Horizonte, 2020, pp. 50-57. Disponível em https://issuu.com/ongcontato\/docs/elipse2

______. Anselmo Duarte: Centenário. In: O Estado de S. Paulo, ed. de 1/3/2020. Dispiponível em https://alias.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,

brasileiro-ganhador-da-palma-de-ouro-anselmo-duarte-tem-obra-ofuscada-em-seu-centenario,70003211082

FERNÃO RAMOS E SHEILA SCHVARZMAN (Org.). Edições Sesc São Paulo. 2018, 600 p. 19 x 24,5 x 3,5 cm. 1,167 kg. ISBN 978-85-9493-084-2.SINGH Jr. Oséas. Adeus Cinema: vida e obra de Anselmo Duarte. São Paulo: Massao Ono Editor, 1993.

BERNARDET, Jean-Claude. Historiografia clássica do cinema brasileiro: metodologia e pedagogia. São Paulo: Annablume, 1995.

CORREIA, Donny. Deus e o Diabo no filme de Anselmo. In: Elipse, n.2. Belo Horizonte, 2020, pp. 50-57.

SINGH Jr. Oséas. Adeus Cinema: vida e obra de Anselmo Duarte. São Paulo: Massao Ono Editor, 1993.