Mazzaropi is a well known traditional figure of Brazilian cinema: he is synonymous with Jeca, the country bumpkin with a shabby checkered shirt, a clumsy walk, and a strong accent from the Brazilian countryside. He is a simple and innocent guy, without malice, but sometimes lazy and hot-headed. Another side of Mazzaropi are his urban characters; those who make a living going around the city, such as a sausage seller or a driver. Mazzaropi plays characters composed in the realm of comedy who resort to stereotypes or exaggerations, seeking to communicate with all kinds of audiences in films that drew crowds to the movie theaters and broke box-office records.

However, there is a darker side to Mazzaropi's "caipira" and urban characters beyond this prism of innocence and naivety. As protagonists, characters like Jeca Tatu are well defined: they push the story forward, they pursue their goals, face challenges, and protect themselves using intelligence and street-smartness. The same cannot be said of the female characters who follow them throughout the plot, especially in the case of their love partners, often played by actress Geny Prado.

Prado's characters, both the country and urban dwellers, are treated by male protagonists in ways that are unacceptable by today's standards. The female co-stars are systematically seen from above by the male gaze, in a world where patriarchal power and the consequent trivialization of violence against women prevail. Name-calling, aggression, manipulation and threats are constant and surprisingly portrayed as comical: they are the jokes themselves. That same innocence of Jeca, when it comes to his relationship with a woman, is pervaded by violence.

Even if we consider the different times these films were made in and the prevailing worldviews of that moment, the frequency, levity and questionable humor associated with situations of humiliation towards female characters remain indigestible. How then is it possible to interpret this facet of comedy that stems from the naturalization of violence against women in Mazzaropi's cinema, consumed for decades by thousands of Brazilians?

Without ignoring the contribution of Mazzaropi's films to Brazilian cinema and its history, I propose a feminist revision of some of the storytelling and filmmaking strategies in Mazzaropi's cinema. My focus is the representation of female characters, especially those played by Geny Prado in the films Jeca Tatu (1959) and O Vendedor de Linguiça (1962).

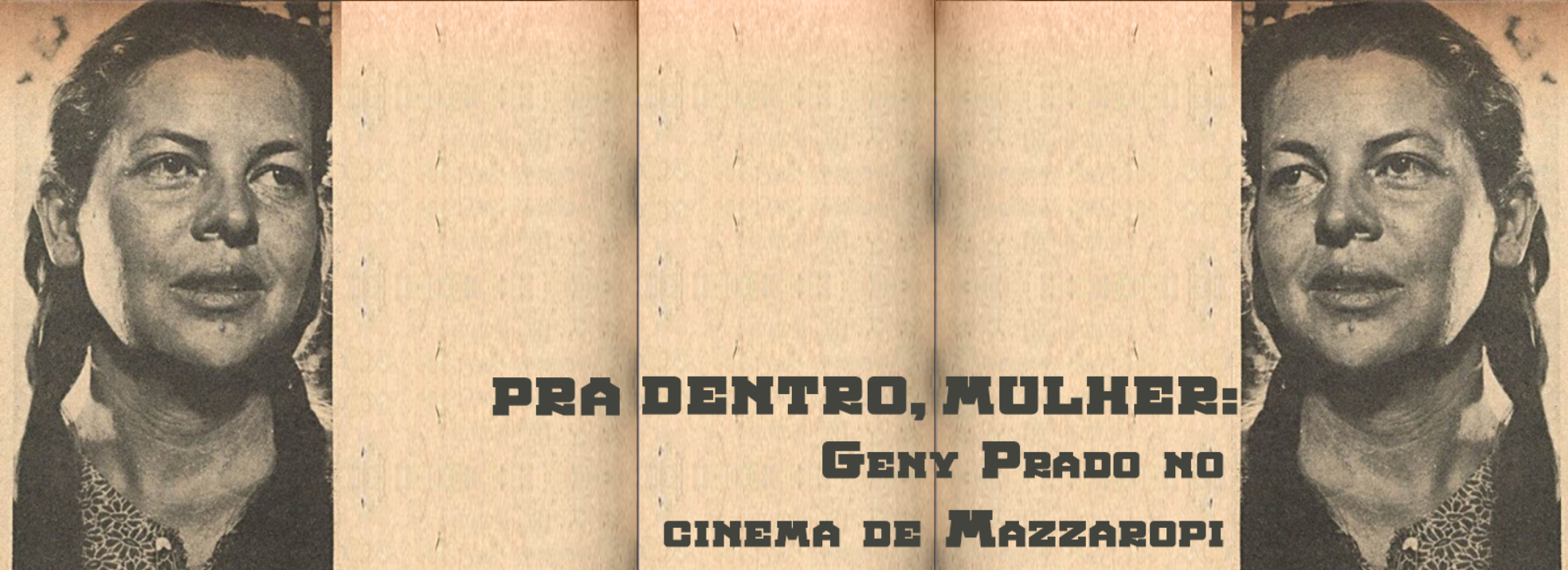

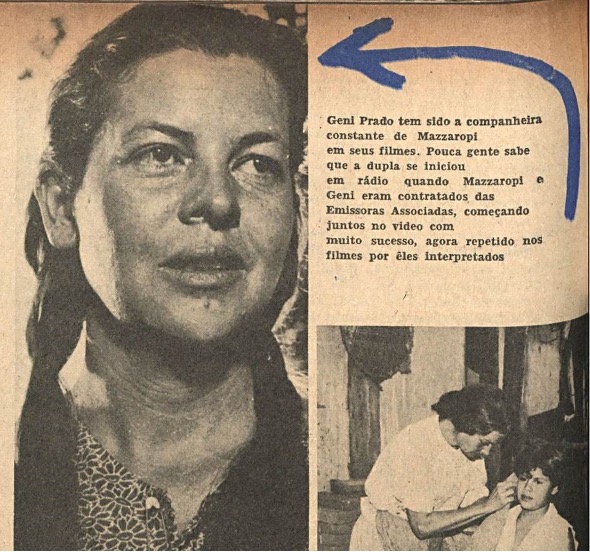

Source: Diário de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, 1962.

1

On the premiere day of a new Mazzaropi film, the lines to buy tickets outside cinemas in downtown São Paulo would go around the blocks, as shown in the famous photograph in front of the now defunct Cine Art Palácio on São João Avenue. With lights and big letters, the theater promoted the arrival of O Noivo da Girafa in 1957.

O cinema de Amácio Mazzaropi é consagrado pela sua realização independente, e pela abordagem de questões próprias da realidade social brasilThe cinema of Amácio Mazzaropi is renowned for its independence and for its approach to issues inherent to Brazilian society - such as caipira culture, the remnants of coronelismo1 in rural areas, and social inequality in urban areas. Throughout his film career, Mazzaropi acted in more than 30 films and directed 13 feature films, even founding his own production company, PAM Filmes (Produções Amácio Mazzaropi).

Mazzaropi is also remembered for being the creator of remarkable characters, such as Jeca, whose name is in the title of eight of his films. Mazzaropi revisited popular cultural figures, such as Monteiro Lobato's Jeca Tatu.2 He interpreted these characters with his own particular style of comedy, even if reinforcing certain stereotypes. He built characters who connected with and became beloved by a general public that eagerly awaited to see him on the big screen.

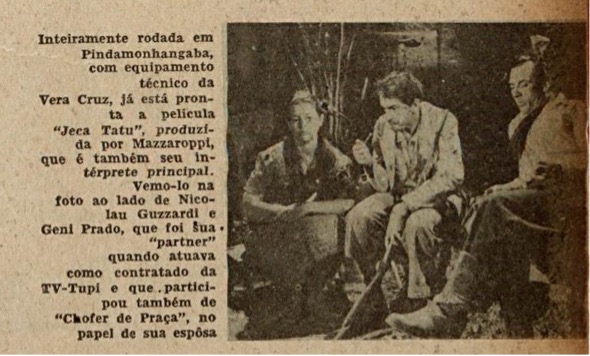

Alongside Jeca and the Mazzaropi urban types, however, we find another figure - the woman, the companion, the wife, the partner of many decades who lives with the protagonist, often played by Brazilian actress Geny Prado.3 Prado was constantly remembered by the media for her role as "Jeca's wife", or even referred to as the "partner", "companion", and "sidekick" of Amácio Mazzaropi.

Source: Revista Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro, 1960.

Born in the countryside of São Paulo state in 1919, in the city of São Manuel, Geny Prado was a Brazilian actress renowned for her characters in Mazzaropi's films. They shared the screen in eighteen films over three decades: Chofer de Praça (1959), Jeca Tatu (1959), As Aventuras de Pedro Malazartes (1960), Zé do Periquito (1960), Tristeza do Jéca (1960), O Vendedor de Linguiça (1962), Casinha Pequenina (1963), O Lamparina (1964), Meu Japão Brasileiro (1965), O Jeca e a Freira (1968), No Paraíso das Solteironas (1969), Betão Ronca Ferro (1970), Um Caipira em Bariloche (1973), O Jeca Contra o Capeta (1976), Jecão... Um Fofoqueiro no Céu (1977), Jeca e Seu Filho Preto (1978), A Banda das Velhas Virgens (1979) and, finally, O Jeca e a Égua Milagrosa (1980). In addition to her film career, Prado acted in more than twenty works for television.

Prado's last film role came five years later in André Klotzel’s A Marvada Carne (1985). In this film, she plays Nhá Policena, the mother of Sá Carula (played by Fernanda Torres). In this final performance, she takes on the role of a country woman; this was Klotzel's tribute to her film career. Prado passed away in 1998.

When looking at Prado's filmography today, a number of problems are evident, as exemplified by the films Jeca Tatu (1959) and O Vendedor de Linguiça (1962). Firstly, her characters are always under the shadow of the protagonist played by Mazzaropi, serving as "bridges" for his jokes - which, as we will see, are often humiliating and derogatory. Second, the characters written for Geny Prado are repetitive: mother, wife, washing, cooking, tidying up, doing the chores that her husband wont do and being mistreated by him. Over the course of decades, her characters, though occasionally fundamental to the plot, were given but a few lines and almost no power of action in the narrative; this being the privilege of the male characters who pushed the story forward.

2

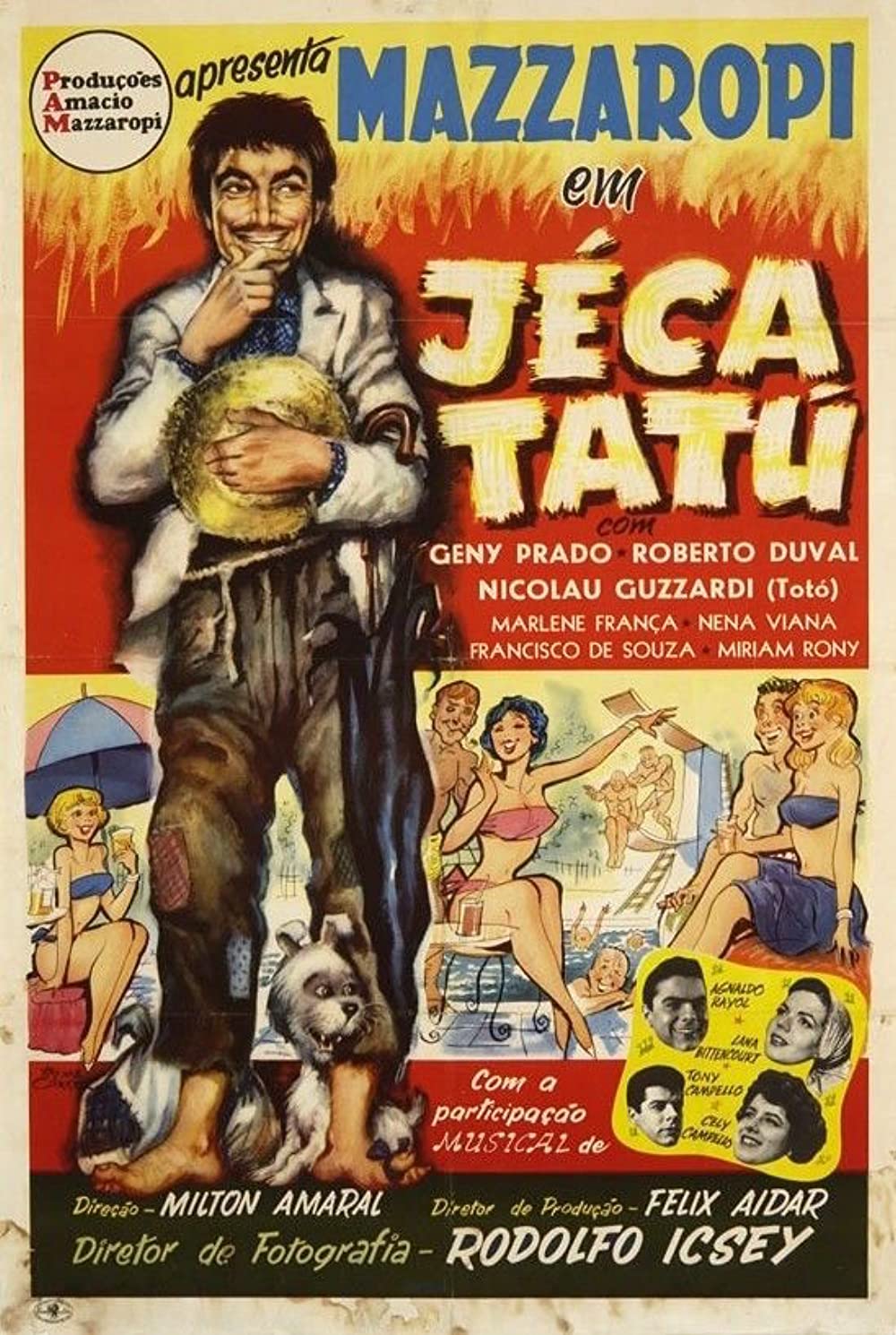

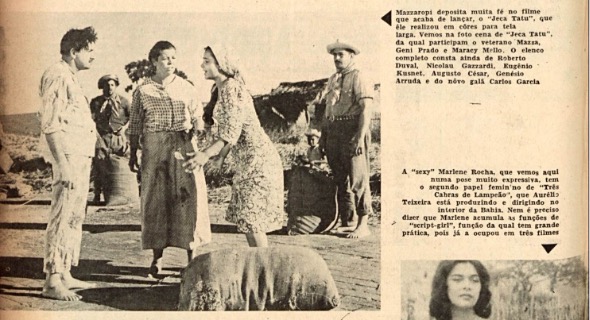

In the classic Jeca Tatu (1959), Geny Prado plays Jerônima, and the issues are there right from the opening sequence. The film, based on a novel by Monteiro Lobato, is directed by Milton Amaral (who had also directed Mazzaropi in his directorial debut, Chofer de Praça), with a script written by Mazzaropi. The film tells the story of Jeca, who, in the midst of disputes over his land and the hand of his daughter, sees his house burned down and leaves for the city to recover his property with the help of a politician.

Source: Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural

The film opens with a sequence that reveals the daily work being done on the farm. Jerônima, an older woman in a worn dress, is already outside, cutting wood to light the stove inside the house. Meanwhile, Jeca is asleep. With the heavy accent commonly attributed to the caipira culture of the Paraíba Valley region, she complains to her husband: "I got up two hours ago and you are still sleeping", a line which emphasizes her double workload.

Then, Jerônima goes out to milk the cow. Jeca takes over, but only to show his wife how to do it properly, underestimating her. After threatening to assault her, he splashes milk at her, making her fall backwards. Not only does Jerônima need to take over Jeca's post, but she is also humiliated when she tries to do so.

The examples add up. When the family house is burned down, Jerônima and her daughter desperately run to try to save a few belongings from the fire. Jeca, on the other hand, remains seated inside the house, watching the flame grow taller, in a state of lethargy. Jerônima asks for his help, but Jeca only tells her to take a pair of his pants off the stove so that it doesn’t catch fire. We can conclude that there is nothing more natural then for Jeca to sit and wait while the women do everything around him.

However, it is worth noting that Jeca's lethargy and laziness originates from the notion that the caipira, afflicted by the insalubrity of rural life before basic sanitation, was a victim of diseases such as yellow fever, which made the body anemic and weak, as was the case with Monteiro Lobato's Jeca Tatu. The same anemic body, however, is the one that deauthorizes and ridicules the wife, dumping the family responsibilities on her, as we see in the scene of the fire.

Source: Cinelândia magazine, Rio de Janeiro, 1961

As Tolentino (2001) argues in his fundamental work on the representation of rural life in Brazilian cinema:

Just as romance plays a marginal role in the central plot, so do the women occupy the same status in relation to the axis of the film (...) It is striking that all the women are invariably mistreated by Jeca Tatu, as an embarrassingly sexist way to get a laugh. (TOLENTINO, 2001, p. 119)

At the very beginning of the film, Jerônima is humiliated by Jeca Tatu, who calls her a "dumb illiterate" and threatens to beat her up. The tone, however, is one of comedy. The gestures, the heavy accent, and the musical accompaniment try to suggest how funny the situation is: even in the countryside, among simple and poor people, the husband shows "who's boss" to his wife, who deserves to be "put in her place".

Source: Revista Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro, 1960.

In O Vendedor de Linguiça, this issue is even more relevant. Released in 1962, O Vendedor de Linguiça is directed by Glauco Mirko Laurelli (who also directed other films starring Mazzaropi and Geny Prado, such as Casinha Pequenina and Meu Japão Brasileiro). The film was written by Milton Amaral and Mazzaropi, and produced by PAM Filmes.

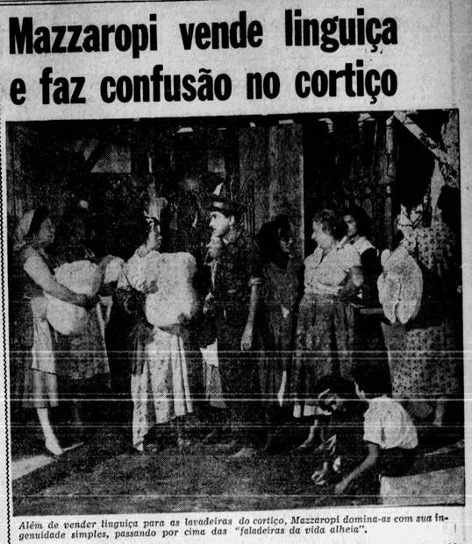

O Vendedor de Linguiça has no caipira traces, instead portraying descendants of Italian immigrants living in urban centers. Interspersed with some romantic musical numbers, the film centers on Gustavo, a sausage seller who drives around in his truck selling meat by the meter, singing to advertise his product. Gustavo is married to Carmela and has two adult children with whom he lives in a house in a small village. There, the older village women form long lines to wash their clothes in a public laundry sink while others go out to work in the city. The plot, in general, centers around small “causalities" and eventualities that end up with all the characters at the police station, such as when a dog steals sausages from Gustavo's truck and Gustavo's daughter gets married.

Source: Diário da Noite, 19/04/1962

Here, the problem lies in how systematic Gustavo's behavior is in humiliating the women around him. The frequency with which he acts to threaten, assault, and belittle women is such that, as the film progresses, it becomes impossible to predict how his character will behave. He might tell some woman to shut up or threaten to hit her with some object, such as a sausage or a ball.

Gustavo's misogyny also manifests itself in relation to the wealthy family of his daughter's husband. He loudly calls the rich woman "a nuisance", forcing her to ride in his truck to travel with strangers and to undress in the middle of the beach against her will. Even if the ridicule of elitism is one of the film's high points, the spontaneous and nonchalant way in which Gustavo curses the rich woman - and not her husband or son - is symptomatic.

It is worth noting that Gustavo is quick to become aggressive and offensive especially with mature or elderly women, such as his wife Carmela, the Italian neighbors, and the wealthy woman. Women who have already lost that which, from a more conventional male perspective, is their greatest value: physical beauty and sexual appeal. They are the most subject to violence disguised as comedy, camouflaged by comic sound effects. Geny Prado's characters, consequently, face such a "curse". Playing alongside Mazzaropi, the wives, already mature and seen as "old", are the greatest victims of his cowardice and hostility, as can be seen when the rich woman wants to throw Gustavo and Carmela out of her house, at which moment the tongue-tied man threatens to hit her with a ball on the head.

In fact, in most cases Mazzaropi's characters only threaten violence. It is rare that his words turn into actions. Furthermore, the threat of aggression with silly objects like a sausage suggests that all this is banal, as if this aggression is not capable of causing fear or pain. Today we publicly discuss the seriousness of psychological violence, but such debate was still embryonic at that time, and inaccessible to most Brazilian women. Hence, the excessive repetition of this type of scene and the comic treatment given to aggressive behavior against women, making it a laughingstock - but only for men.

3

The naturalness with which Mazzaropi's characters address women in a pejorative way is what allows us to ask: what does it mean to despise women with such ease, in that historical and social context, at that moment in Brazilian film history and in those audiovisual works capable of reaching large audiences and filling movie theaters?

In these cases, it is possible to question whether there is violence, misogyny, or any contempt addressed specifically to women. One might say that it was a different time, with a different worldview, and there were different ways of coexistence between women and men that did not boil down to the contemporary view that, fortunately, has gained from the countless conquests of feminism and the struggles of various social movements for equality.

On one hand, it is possible to point out the open misogyny that manifests itself in several Mazzaropi films as a result of a naturalization of violence against women in Brazilian society. This misogyny is not born in the cinema, but is reflected in the audiovisual production of the country. On the other hand, we do not seek to reduce such cinema to this issue, all the more so because of its reach and repercussions throughout decades in Brazil.

The films of Jeca and Mazzaropi's urban films do, in fact, touch on aspects of social reality and serious issues, bringing moments of social criticism in the midst of comedy. This kind of social criticism can be found, for instance, in the scenes that expose the inequality between classes and the abyss between the poorest and richest in Brazil. In O Vendedor de Linguiça, when Gustavo and Carmela go live in the family home of their daughter's husband, a gesture of generosity by the sausage seller causes a malaise that is typical of the naturalization of misery. The sequence begins with a dubious joke: during a walk through the rich neighborhood, the couple sees a homeless woman who says she doesn't want a job because her job is "begging" - an opinion that is repeated in Brazilian common sense, that poverty is an "excuse" for not working for those who are vulnerable. Gustavo is moved to learn that the woman has no home, so he invites her to spend the night in his guest room, stating that her whole family is welcome to do the same.

Through the open gate, however, arrive several other men, women, and children, who occupy the empty spaces of the mansion. One of them says he is ashamed to be in such a beautiful house, as he is so dirty. However, generosity has its limits. Their arrival is accompanied by a suspenseful soundtrack, as if the entrance of the poor into the house was a reason to be frightened. Or, in a scene that is embarrassing because of the frivolity with which the Holocaust is mentioned, a rich neighbor is impressed to see the poor, saying that the mansion would become a "concentration camp". Under pressure from the owners of the mansion and their neighbors, who are already calling the police, an embarrassed Gustavo is forced to expel all the homeless people from the house.

The sequence is striking for its portrayal of the proximity between extreme poverty and extreme wealth, a pressing issue in the history of Brazil which has become emphasized under the current administration. The film approaches the issue with a certain seriousness, at first with sparse humor, but later with a sentimental and melancholic potency not seen until that point. To add to Gustavo's rebellion, the soundtrack is kept in a tone of suspense and conflict. Hence, the seriousness of the problem is evident, and the seriousness with which the film represents it - which doesn't occur, not even remotely, in relation to the treatment of the female characters.

Mazzaropi's films are remembered through a bias of beautiful nostalgia, as the fruit of a long-lost innocence, of a sweetness and ease of everyday life and of life in the countryside that is no longer seen in the many large Brazilian cities and in changing social customs and practices. However, these films, watched by thousands of Brazilians since their release until today, end up reinforcing stereotypes and a misogynistic mentality that, even now, are still repeated: "women can't drive", "women only cry", "women talk too much", "women like to be beaten", "a woman's place is in the house", or even "a woman's place is doing the laundry", as seen in the first scene of O Vendedor de Linguiça.

On the other hand, it is worth thinking: by threatening the women in his films, wouldn't Mazzaropi be "denouncing" the naturalness of such behavior in Brazilian society, and opposing it? The films say otherwise, as one can see that the scenes of aggression towards women are not based on a critical tone, but are the very source of comicality, reinforced by pathetic sound effects, physical comedy and the exaggerated tone that marks Mazzaropi's style of comedy. Thus, this kind of scene serves to demonstrate how acceptable it was to ridicule a woman and to find it funny, as a form of humor authorized by the sexist mentality established in Brazilian society in the decades when Mazzaropi's films thrived, instead of criticizing the sexism of those times.

If we emphasize from the beginning that, despite what has been pointed out, Mazzaropi's filmography is a milestone in the history of Brazilian cinema and contributes to discuss social problems such as inequality and the legacy of coronelismo, for example, what is the point of a feminist and contemporary reading of films produced more than sixty years ago?

The critique of anachronism claims that we should not look with contemporary eyes at what was made in the past. If this is so, then it would be ineffective to review the cinematographic techniques for the representation of country women in Mazzaropi’s cinema. It would also be unproductive to question openly racist postures and words in Mazzaropi's comedies - and in many other works of Brazilian cinema, since in late works, such as Jeca e Seu Filho Preto, the film portrays racial prejudice and stands against discrimination.

But the representation itself needs to be analysed. The way art creates images about reality, based on interpretations of such reality, culminates in the repetition of stereotypes. For decades, film has contributed to create the idea that caipira women are crude, and therefore naturally subject to the violence that was camouflaged in Jeca’s innocence. For decades, film showcased and reinforced images which implied that it was natural to threaten a woman like Carmela in a marital relationship and that the male power in a marriage was unquestionable. To critique such standards, dismantling stereotypes and, finally, "deconstructing" the foundation that suggests comical and banal scenes of oppression to women, are resources that allow us to change the focus and find new ways to see what is being portrayed.

Authors such as Tolentino (2001) and Fressato (2008) state that, by assuming the role of a “coronel”, Jeca goes from oppressed to oppressor, and ceases to be a mere "jeca”.4 Much earlier in the film, however, we see Jeca as an oppressor - not in the key of class difference or political power, but in the dimension of sexual difference; who benefits from violence to subjugate women, given the levity with which he threatens, ridicules, and humiliates Jerônima, in acts that at first sight are harmless, like mere threats, but are well rooted in the male mentality and daily life.

In the end, the women played by Geny Prado showcase symptoms of a time that we sometimes remember with nostalgia and associate with a certain lost innocence. Both films begin with sequences that show, as if it were normal, the excessive workload of the wives and the carelessness of their husbands. Both films let us glimpse at disrespected, destitute women, who get used to that kind of life due to the violence of repetition and their lack of education.

It is not by chance, after all, that it was only in 2021 that psychological abuse within marital relationships was criminalized in Brazil. It is an instilled practice that reveals the seriousness of the situations to which women are subjected in Brazilian society, as seen in Mazzaropi's films. So, we perceive Mazzaropi's cinema and Geny Prado's presence as a historical register of male perspectives and attitudes over the female figure, internalized via comedy by audiences and Brazilian society, in many cases up until the present day, which it is up to us to overcome.5

1. A system of power control led by "colonels" mainly in rural regions of Brazil that marked the country's first republican period beginning in 1889.

2. Monteiro Lobato (1882-1948) is considered one of the greatest Brazilian writers despite his racist and eugenicist stance and writings (see Habib,2003). Jeca Tatu is one of his literary creations, which initially represented peasant populations in a pejorative way, as a lazy figure unfaithful to progress. Later, Jeca is transformed into the "poster boy" of the campaign for the medicalization of rural areas and for basic sanitation in rural Brazil.

3. Or Geni Prado, as found in period records such as film magazines and newspapers from the 1950s and 1960s.

4. In Brazilian Portuguese, "jeca" became an adjective, being used to mean a person of bad taste, without refinement, a "caipira" in the pejorative sense of the word.

5. This research is further developed in the dissertation Representações da mulher caipira no cinema brasileiro: Amélia (2000), de Ana Carolina, e Uma vida em segredo (2001), de Suzana Amaral, and in articles and more publications from this author.

REFERENCES

Fressato, Soleni. O caipira Jeca Tatu: uma negação da sociedade capitalista? Representações no cinema de Mazzaropi. IV ENECULT - Encontro de Estudos Multidisciplinares em Cultura 28 a 30 de maio de 2008.

Habib, Paula Arantes Botelho Briglia. "Eis o mundo encantado que Monteiro Lobato criou": raça, eugenia e nação. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Campinas, 2003.

Tolentino, Célia Aparecida Ferreira. O rural no cinema brasileiro. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2001.