The Cinemateca Brasileira (CB, or “Brazilian Cinematheque”), the leading audiovisual heritage institution in Brazil, is going through its worst-ever crisis in 2020. As a result, its extensive collection and elaborate technological machinery are threatened, as well as the knowledge that permeates from both. At the beginning of the year, a flood occurred in the Cinemateca’s warehouse, drastically affecting part of the film and equipment collection stored there. Since August 2020, the collection and facilities are without proper technical support; and at this moment of writing, there is no news of an immediate resolution that meets the urgency. Inaction and neglect with the Cinemateca Brasileira are just two examples of the Brazilian government’s perversities, which additionally include the structural dismantling of the public health, education, and cultural systems,1 and the ecocide and genocide of the country’s native and black populations, the latter of which has been accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic. The Cinemateca crisis took on unprecedented proportions in 2020, but its origin came earlier, going through the administrative and political turmoil of 2013 and a fire in early 2016. This article discusses the work carried out at the institution in mid-2016, the challenge of its continuity after the team’s reduction in 2017, the alleged solution with a new management model in 2018, and the 2020 hecatomb.2 This text also presents a few conjectures about the relationship between Brazil’s audiovisual heritage and its audiovisual production industry. The series of crises over the last 74 years, marked by the four fires and the flood, are the broad consequence of what Brasília-based museologist Fabiana Ferreira highlights in her thesis “A Cinemateca Brasileira e as políticas públicas de preservação do acervo audiovisual no Brasil” (2020).3 She claims, “the only stable aspect in public policies for audiovisual preservation is its inconstancy. A succession of disagreements and disarticulations by the political agents responsible for the creation and implementation of policies without a real national governmental project that crosses mandates” (2020, p.109). According to Hernani Heffner, chief curator of the Cinemateca do MAM in Rio de Janeiro, this is not only the biggest crisis in the history of the Cinemateca Brasileira, but also the biggest crisis of Brazilian audiovisual heritage.4

Overview of the Last Two Decades

Brazil is a federal republic of continental dimensions – the fifth-largest in territorial extension. It has 26 states and a federal district. The country has undergone two re-democratization processes, the most recent in 1984 after the end of the military dictatorship. In the 21st century, Brazil has had economic growth, a reduction of social gaps, and extreme-poverty rates. Universities flourished and the audiovisual industry solidified through new federal policies and programs as a result of the investment policies of the Audiovisual Secretariat (SAv) / Ministry of Culture (MinC),5 and the Audiovisual Sector Fund (FSA).6 These investments allowed new professionals to emerge in the film production sector and the consolidation of new film production companies, which, in turn, supplied an increasing number of new films each year. Eventual municipal and state resources for film production were added to the federal ones. However, Laura Bezerra observes that while the government invested in decentralizing cultural production policies, the same did not happen with film preservation (2015). While there were substantial investments in the Cinemateca Brasileira during this period and after the inclusion of the CB in the SAv’s organizational chart, there were also few political discussions about the implementation of policies and actions for the field in a profound way.7 This is a problem that is fundamental for understanding the development of the current crisis. As Fabiana Ferreira diagnosed, “The Cinemateca does not act in the creation and implementation of preservation policies, either by conducting discussions and holding dialogues with the sector or by actively participating in political spaces at the federal level, such as the National Film Council, for example. There was also no structured dialogue with other memory management entities” (2020, p.108). The State’s insufficiency in their management of Brazilian heritage causes profound reverberations, especially affecting the audiovisual production industry which seems to not recognize preservation as a necessary element for their works. Still, the current Cinemateca Brasileira crisis has become yet another argument for the decentralization (and increase) of investments in audiovisual heritage nationwide.8 Brazil has many federal, state, municipal, and private heritage institutions that are not in the spotlight and that also demand urgent actions and resources.

Over the last few decades, there has been constant maturation in the field of audiovisual preservation. For example, the establishment of specific financing programs; the distribution of new publications; the creation and growth of the festival Mostra de Cinema de Ouro Preto (CineOP), where the National Meeting of Archives and Audiovisual Collections takes place;9 the formation of the Brazilian Association for Audiovisual Preservation (ABPA) and the elaboration of the National Plan for Audiovisual Preservation (PNPA).10 Also, there has been a growing number of Preservation-related events each year.

Cinemateca Brasileira – A Brief History

The Cinemateca Brasileira has had several administrative arrangements. It began as a civil society organization and later moved to the public sphere. Its long history includes many setbacks with some positive developments. The writer, essayist, critic, researcher, professor, and activist Paulo Emílio Sales Gomes (1916-1977) is the protagonist in the creation, defense, and management of the Cinemateca Brasileira. Paulo Emílio’s impact on the field of Brazilian Cinema is broader than his work on the Cinemateca itself. His work was fundamental in the valorization of Brazilian cinema, in its qualification as a historical document, in the defense of its preservation, and in creating university cinema courses. Paulo Emílio was also active in international politics as a regular member of the Executive Committee of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) between 1948 and 1964, eventually becoming the organization’s vice president. He is also a renowned author in historiographic studies of cinema, with publications on the French director Jean Vigo and the Brazilian filmmaker Humberto Mauro, among others. As a teacher, he was vital in the formation of numerous important scholars, film critics, and preservationists, such as Carlos Augusto Calil, Carlos Roberto de Sousa, Ismail Xavier, Jean-Claude Bernardet, Maria Rita Galvão, and Olga Futemma – some of whom continued his work at the Cinemateca Brasileira.

In consideration of the many publications on the Cinemateca Brasileira in Portuguese and the limited English repertoire that exists in comparison, what follows here is a brief overview of the institution’s key historical moments. In 1940, intellectuals from São Paulo created the Clube de Cinema de São Paulo (São Paulo Film Club), which promoted the exhibition of films, conferences, debates, and publications before being closed in 1941 by the country’s then-reigning dictatorship government. In 1946, Paulo Emílio went to France to study at the Institut des Hautes Études Cinematographiques (IDHEC). He grew even closer to the Cinemathèque française, an institution founded in 1936 with which he had contact since living in Paris during the previous decade – the period when his passion for cinema awoke. The second São Paulo Film Club was created in 1946, and in addition to its previous activities, it began to develop the initiative of prospecting and preserving materials from Brazilian films. 1946 is therefore considered to be the milestone year of the Cinemateca’s creation. Paulo Emílio affiliated the Club to FIAF in 1948. In the following year, the Film Library was created, and then connected to the newly created Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo. In 1956, the archive was detached from the museum and became the Cinemateca Brasileira, a non-profit civil society. The Advisory Council was formed the same year.11 As a result of the self-combustion of a cellulose nitrate reel, the Cinemateca’s first fire occurred in the summer of 1957, which “completely destroyed the library, the photo library, the general archives, and the collection of devices for the future cinema museum, as well as one-third of the film collection” (Gomes, 1981, p. 75). The tragedy elicited support and donations from national and foreign entities, and the Cinemateca resultingly gained space in the largest urban park in São Paulo, Ibirapuera Park. In 1961, the Cinemateca became a non-profit foundation, an essential status for its autonomy and ability to raise public resources.

In the following year, a new non-profit civil entity called the Sociedade Amigos da Cinemateca (SAC, Portuguese for “Society of Friends of the Cinematheque”) was created to assist the Cinemateca in its management of financial resources and to develop various activities to support the Institution. Initially, the Cinemateca mainly held film screenings, but from the 1970s onwards preservation became its axis partly due to the declining state of its collection. The late 1960s and mid-1970s formed a critical period for the institution, as it had few employees and much voluntary work. Unfortunately, the Cinemateca was unable to pay its annuity fees, and therefore it was disconnected from FIAF in 1963. The CB became an observer in 1979 and received its full FIAF membership again in 1984. The Cinemateca’s second fire occurred in the summer of 1969 for the same reason the previous fire was triggered, resulting in the significant loss of film-related materials. In 1977, the institution’s Laboratory was created with equipment from commercial film laboratories that had been deactivated. Paulo Emílio passed away from a heart attack that same year.

In 1980, an operations Center was opened in São Paulo’s Conceição Park for documentation and research work. The third fire occurred in the autumn of 1982. As a result, a move was made to incorporate the Cinemateca into the public sphere. In 1984, the CB Foundation was extinguished, and the Cinemateca was attached, as an autonomous organ, to the National Pro-Memory Foundation. In 1989, a cinema12 theater was rented to screen the archive’s collection in the busy neighborhood of Pinheiros, which significantly leveraged São Paulo’s cinema scene. By the end of the decade, the Cinemateca staff consisted of about 40 people (many of them former students of Paulo Emílio), 30 of whom were hired with formal contracts.

In 1990, the government extinguished the National Pro-Memory Foundation and the Cinemateca was incorporated into the Brazilian Cultural Heritage Institute (IBPC). This organization transformed into the (still-active) National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN) four years later. In 1997, the Cinemateca’s current facility was founded, a heritage site converted from a slaughterhouse after nine years of reformations. The definitive headquarters13 aggregates the conservation and screening departments that had previously been scattered throughout the city of São Paulo. This centralizing was a crucial element in the institution’s consolidation process after decades of scarce resources, precarious infrastructure, and oscillations in institutional dynamics.

In 2001, a vault with a proper climatization system was inaugurated with an initial capacity of one hundred thousand reels. In the same year, the Brazilian Cinematographic Census project began14 with funding from BR Distribuidora.15 The Brazilian Cinematographic Census project was an essential step for appraisal and basic conservation procedures in the collection,16 and the training of technicians. The project “was organized around four basic axes: the appraisal and examination of the existing collection, which was previously concentrated and dispersed; the duplication of reels threatened by deterioration; the dissemination of the work and its results; the study of legal measures for the protection of audiovisual heritage” (Souza, 2009, p.258). In 2003, upon resolving that IPHAN was not meeting the scope of its tasks, and after deliberation by the Council, the CB was attached to SAv/MinC. In the following years, the resources transferred by MinC gradually increased. In 2003, the CB implemented a short internship program for technicians from other institutions. From 2004 to 2006, the Prospecção e Memória (Prospecting and Memory) project followed the Census project, especially concerning the cataloguing of Brazilian movies compiled in the Cinemateca’s Filmografia Brasileira (Brazilian Filmography) database.17

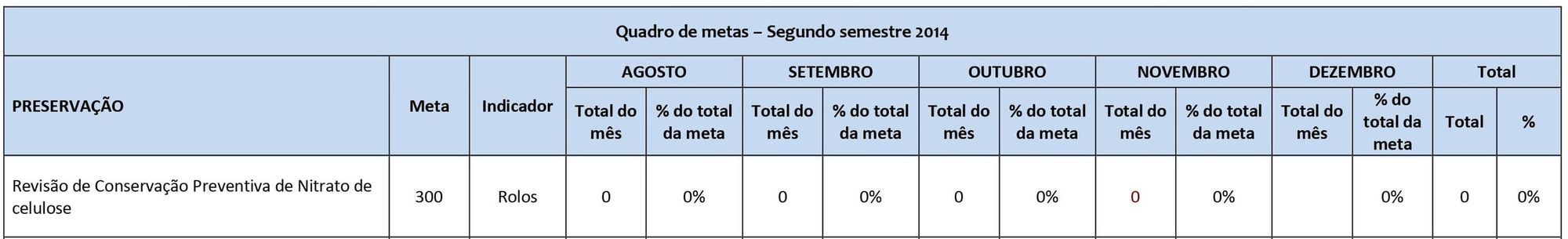

In 2005, SAv created the Brazilian Audiovisual Information System (SiBIA) which was coordinated by the CB. It was “a program that aimed to establish a network that currently counts on more than 30 institutions that dedicate themselves, primarily or in subsidiary fashion, to the preservation of moving image collections throughout Brazil”.18 In 2006, the CB hosted the 62nd FIAF Congress, “The Future of Film Archives in a Digital Cinema World: Film Archives in Transition”. In that same year, on the institution’s 60th anniversary, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva became the first (and only) president of Brazil to personally visit the CB, with representatives’ delegation. In 2006, the CB published the “Manual de Manuseio de Películas Cinematográficas” and the “Manual de Catalogação de Filmes” da instituição (Film Handling Manual and Cataloging Manual), which became a primary reference for other preservation institutions, as scarce technical publications existed in Portuguese at the time. In 2008, SAC became a Public Interest Civil Organization (OSCIP) and, since then, the transferring of resources to projects carried out at the Cinemateca has been massive. Under SAC management, SAv’s projects were carried out in an agile way, unlike the Ministry’s bureaucracy. At that time, many of SAv’s programs were achieved at the Cinemateca, such as “Programadora Brasil”.19 As of 2008, annual reports that described the archive’s operations throughout the year were published online,20 except for the following years: 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2019. As a result of the census, the lab preserved and restored numerous films and created new access materials. In 2009, the CB launched the DVD box set “Resgate do Cinema Silencioso Brasileiro” (Rescuing Silent Brazilian Cinema), with 27 early films accompanied by new soundtracks. In 2011, a secondary site was opened in the neighborhood of Vila Leopoldina21 to store films, documents, and equipment. In 2012, the first edition of the magazine Revista da Cinemateca Brasileira was published and in the following year, its second edition was published.22 In 2013, a political-administrative crisis was initiated, and the Cinemateca’s executive director was dismissed without due dialogue with the Council or appropriate measures taken for finding his replacement or formulating a transition plan. The Comptroller General of Brazil carried out several audits regarding SAv resources executed by SAC and the acquisition of collections by the government.23 At the end of the year, of the 124 employees that had been working before the crisis, just a few remained, including 22 public servants directly linked to the Ministry.24 From the 2014 Report, it is possible to verify that some of the institutional workflow continued. Below, I present data that reflect the interruption of work in 2014 (and 2015). This work stoppage would drastically affect the CB’s collection:25

In the summer of 2016, the Cinemateca’s fourth fire occurred, again due to a nitrate reel’s self-combustion. The loss was estimated at a total of 1003 reels of cellulose nitrate films referent to 731 titles. In addition to the discontinuation of the nitrate collection analysis after the 2013 crisis, technicians realized a few years later that someone had allocated new reels at the Cinemateca’s nitrate vault without the proper removal of the transport packaging. This could have been avoided if the technical team had been tasked with allocating and reallocating works within this film collection. This oversight potentially created conditions for a microclimate prone to self-combustion, and it could have been the second factor responsible for the fire. However, the first and most important factor for the fire will always be the government's neglect, given the lack of resources for the institution’s primary activities.

Cinemateca Brasileira – 2016 and 2017

The 2016 fire coincided with hiring 11 new technicians, an action made possible by a one-year contract signed between SAv/MinC and the Educational Communication of the Roquette Pinto Association (Acerp) at the end of 2015. Altogether, until the middle of the year, 42 technicians were hired, in addition to the 15 public servants directly linked to MinC. Third-party companies were contracted for essential services (maintenance, cleaning, security, and IT). Seven technicians were also hired for the flow of Legal Deposit,26 made possible by the Brazilian Film Agency (Ancine). The tone set by Cinemateca Brasileira director Olga Futemma27 in the 2016 Report is one of optimism and pride in meeting the goals established in the contract’s Work Plan, though there are due signs of the difficulties and challenges created from the discontinuity of work in the previous years in the report as well. A highlight of the work carried out as a result of the fire:

“Appraisal and reporting the losses […]; examination, separation by technical deterioration [...] for lab processing; provisional allocation of the remaining 3,000 nitrate reels; creation of a project, for the burnt vault, for fire prevention devices [...]; basic renovation of the vault, carried out by the Cinemateca’s team, for the return of the collection [...]; technical disposal of fire residues”.

Despite the disaster, MinC did not provide resources for preventing further fires.28 Another challenge explained by Futemma was the situation of the Laboratory, which had undergone a work stoppage. “The scenario was heartbreaking”, she claimed. To stress its importance: The Laboratory at the Cinemateca Brasileira is the most complete (and possibly last) of the photochemical labs in South America. It has the ability to process film-to-film, including 35mm and 16mm, b&w of all materials and color prints. The Lab can process smaller gauge film formats such as 8mm, 9.5mm, and 16mm film as well. In addition to its capacity to specifically work with film, the Lab also contains a wealth of digital equipment. These include the ability to scan 35mm film-to-digital (HD, 2K, 4K, 6K) and the ability to print digital back-to-film, such as printing digital to 35mm film. The Lab can scan several video formats to digital, including U-Matic, Betacam SP, Digital Betacam, DVCam, and others. It also has the capacity to conduct digital image and sound manipulation, including color correction and restoration. The machinery has even been outfitted over the years to process materials with advanced deterioration.29 However, due to the lack of staff over previous years and the resulting lack of maintenance and parts, it became impossible to resume some of these workflows.

The Cinemateca’s current audiovisual collection comprises about 250 thousand nitrate, acetate, and polyester film reels, in addition to a large gathering of magnetic tapes and reels, and approximately 800 terabytes of digital data – mainly comprised of digitized materials from the collection and Legal Deposit materials. The film-related collection comprises about one million documents, such as posters, photographs, drawings, books, scripts, periodicals, censorship certificates, press materials, and documents from personal and institutional archives.30 There is also a non-cataloged equipment collection. In recent times, the institution’s resources and activities were divided among the following departments: Film Preservation, Documentation and Research Center, Access – Programming31 and Events, Administration, Maintenance and IT.

In the Film Preservation sector, several task flows were executed throughout 2016: monitoring of the climate control of the deposits, movement of materials according to their physical state of deterioration, documentation review, applicant services, and emergency duplication of materials (which will be discussed more later on). A significant element of our workflow was to document mandatory preservation actions in a collective fashion, a task for which the Cinemateca lacked sufficient resources. After months of corrective maintenance and evaluation of lab chemicals and raw film stock, the processing of deteriorated film materials began: per the 2016 report, “the selection was made by considering the technical conditions of the materials, [with an investment of] less time and resources in the complementary actions of a single work so that it would be possible to make feasible actions, although incomplete, in a wider number of materials”.32

Due to goals established in the Work Plan and the limited available time and staff in 2016, the selection of films for processing in the Lab was only carried out by one technician. However, the ideal context would be one in which there were institutional debates and discussions about the film selection process. Attention was taken not to select consecrated narrative feature films,33 but instead, to cover “material from fiction films, documentaries, newsreels, domestic films, and scientific films… without subjective evaluation of the content of the works or any curatorship” (2016 Report). The selection prioritized the state of deterioration of the materials and not their content. An aspect of this workflow worth being critical of is that many worthy films were not being selected, which possibly further increased their ostracism. Throughout the analysis process, some materials were evaluated as not processable. Since these films were considered unique, if they were not processed and restored, it would represent the death of the images and sounds they contain. Countless materials so deteriorated that they did not meet the conditions for a complete duplication. Also, newly generated materials often contained photographic marks of deterioration that were existent in the material prior to them. During this workflow, the film stock purchased in previous years was used. However, a few years later, the archive ran out of raw film stock for its workflow.

The eventual losses of films and the specificities of processing them raised awareness around the need to create a standardized methodology for evaluating and documenting films. Because every film is its own unique material, this standardized methodology could help guide preservation and access actions. The “preservation status” was thus created, and this categorization was integrated into the film’s internal documentation and incorporated into communications with the rights holders. This documentation would include the categorization of the preservation status, like “partially preserved” and “partially lost”, with recommendations such as lab processing or research for new materials.34 Since these categories would frequently vary throughout the year as the materials’ physical conditions could change, the original date that a film’s status was proclaimed was as important as the actual status itself.

The database solution used at the Cinemateca Brasileira was WinIsis,35 which is a poor tool for complex data analysis. Several workflows – analysis, outflow of materials, and creation of new materials – required constant updating of the audiovisual database, which was interrupted because of the institution’s broad structural problems. In parallel, the open-source and Web-based project Trac36 was purposed and standardized for internal documentation workflow on the intranet. Trac was basically a Wiki documentation and ticket system. According to the 2017 Report, this intranet “makes it possible to maintain information horizontally among sectors, collaboration in the construction of documentation, the continuity, and organization of information on the same platform, […] used to document different internal procedures; norms and instructions for internal documentation; reports and texts related to the institution; information related to external requests and data of materials analyzed and processed”. The effort to keep internal documentation accessible, horizontal, and transparent, consistent with a memory institution’s role, did not comprise communications with Acerp and the projects sent to the Ministries. An essential element for those years was the investment in technological development, as documented in the 2017 report, which allowed the analysis of information from the database in a dynamic way and the research for solutions to foster the institution’s autonomy.

The ClimaCB project is worth mentioning, as it allowed for the online monitoring of climate control. It is a combination of open-source software and hardware that would list which guidelines and codes would be available in Git for free use. Unfortunately, the project was not published. Considering the potential cardinal role of the CB within the scope of Brazilian audiovisual heritage, it is clear that participation in technical discussions and the publication of proposals and technological solutions are both wanted and needed.

During the two years under the Service Contract, Olga Futemma held meetings with the technical staff to share news, impressions, and strategies. The meetings reinforced the notion of the team’s proportion and strength and served as an injection of spirit. Another positive development that brought the preservation team together was the Cinemateca’s new website, as the previous site had had obsolete navigation and tools. A moment of heightened visibility came when a short video made by the technical team showing the history of the institution’s logo dating back to 1954 became widely shared on the internet.37

The staff in the Film Preservation department was balanced between former technicians who ensured the continuation of workflows and new technicians who provided fresh evaluations for the workflows. The difficulties in creating interpersonal relationships during previous years and feelings of insecurity over the 2013 crisis were negative aspects that we avoided discussing within the workspace.

2016 was marked by the autonomy and intense communication of the technical team, but also by setbacks. In May, MinC published a public tender for electing a Social Organization (SO) to undertake the CB’s management. This was still during the Presidency of Dilma Rousseff. Shortly afterward, a misogynist coup occurred – by dint of the process of impeachment which eventually led to Rousseff’s ousting and the taking of power by her former vice president. Shortly after he took office, he tried to end MinC, but reversed this position in response to intense popular pressure. The new Minister of Culture canceled the public tender for electing a Social Organization for the Cinemateca Brasileira, and it was released months later with changes.

July 2016 brought one more surprise: after a restructuring of MinC, five positions at the Cinemateca were eliminated. At the time, these positions were occupied by the director and experienced technicians. A new director would be indicated by the Ministry, without the necessary expertise and without the Council’s participation, a move considered to be unprecedented at the time. Audiovisual associations issued letters against this announcement and the Council issued a manifesto38 in favor of revoking the layoffs and proposing a partnering with the Brazilian Museum Institute (IBRAM). The stance eventually led to the reversing of the dismissals and a rehiring of the director and technicians.

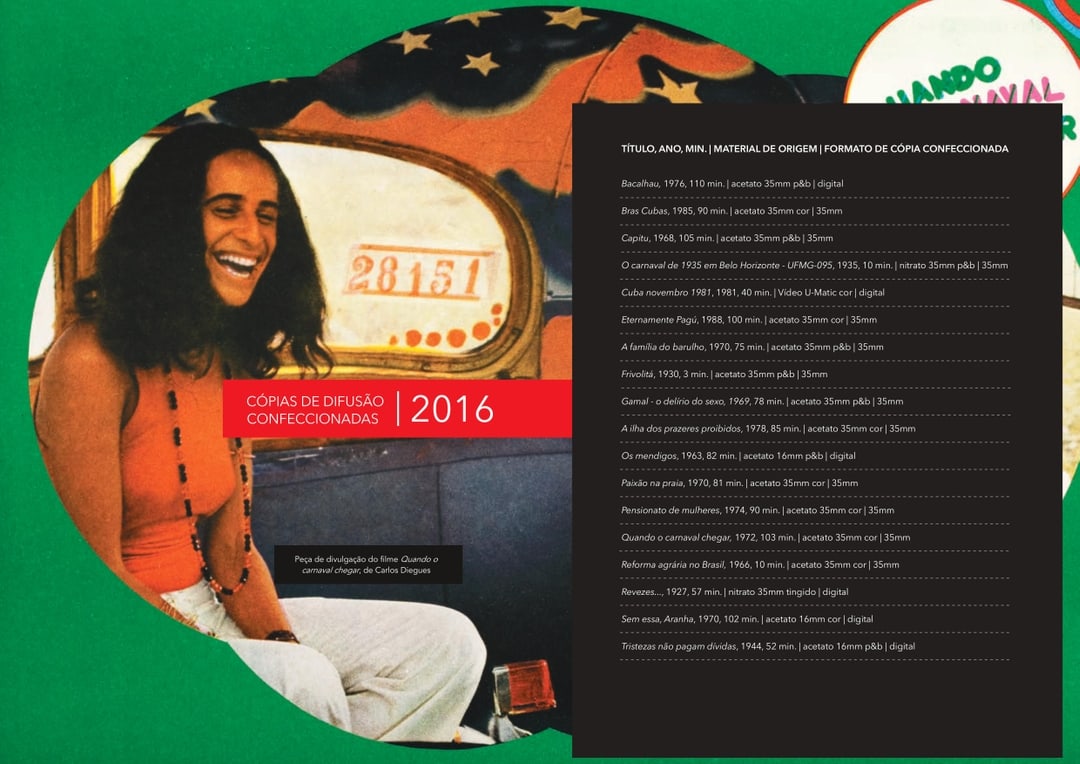

In the following months, the CB and SAv/MinC jointly sought to prevent a gap between the expiration of the Service Contract with Acerp, which would end in December, and the new management determined by the selected SO after the public tender. A solution was finally found a day before the contract’s expiration – an extension until April 2017. But, “as the residual value is not enough to remunerate for four months all technicians previously hired, it was necessary to reduce the staff (by about 75%) and, as a consequence, workflows”, according to that year’s report. The year ended with mixed enthusiasm for the future of the CB. While there was Paulo Emílio’s centenary celebration, which included the launch of a series-specific website,39 courses for the general public and publications devoted to Paulo Emílio’s work, there was also discouragement for the downsizing of the Cinemateca’s team, as the staff would not be the same size again until June 2017. The impact on the CB of the substantial reduction in technicians is evident, as can be observed in this 2016 and 2017 lab processing chart which reflects the amount of processed material:

In May 2018, the contract with the SO for the CB’s management was signed, followed by a ceremony attended by the then-Minister of Culture, who claimed that “the crisis is over” thanks to the new management model. Acerp, which managed the CB via a Service Contract that began in 2016, was the SO selected in the public tender. In the case of the Cinemateca Brasileira, this legal indenture would contribute to the current crisis. It was not legally possible for Acerp to directly sign a contract with the Ministry of Culture (to which the Cinemateca was linked) due to its preexisting contract with the Ministry of Education (MEC). Thus, the management of the Cinemateca was officially fulfilled by an amendment to the main contract.40

After the contract’s signing, Acerp appointed a new director without the deliberation of the Council, which was then ostracized from further organizational discussions. Acerp’s first action that had a substantial impact on the dynamics of the institution’s technical team was creating a new customer service department, installed for meeting the growing number of outside requests, especially requests for access to the Cinemateca’s audiovisual collection. The other sectors’ services and fulfilling access requests never stopped; the main bottleneck was providing access to the audiovisual collection. Every collection request was in theory recorded, answered, and eventually met in the order of their arrival, the possibility of completing the request, and the processing time to complete it. Despite this protocol established by the team, a sign of the CB’s subjugation would be the intensification of projects becoming prioritized over others, as determined by the Minister or the board of Acerp. This non-conformity with the institution’s protocols generated personal discomfort among the preservation team.

For the Film Preservation department workers, the new customer service meant there would be no more contact with researchers and producers, who were used to the greater agility in meeting their requests that the larger staff provided before 2013 and were frustrated by the reduced team’s limited response. Besides, the dialogue with producers and researchers about their practices showed a lack of understanding of preservation’s importance. Furthermore, this dialogue proved to be shortsighted from a market perspective when accessing materials held in the CB for digitization without proper processing.41 Another indication of incomprehension and disrespect for the preservation team was that the agreed upon financial compensation that the institution was expecting never arrived. This matter was elegantly noted by Olga Futemma, who stated in the 2016 Report: “some of the bad situations we faced were due to: tight deadlines; the total disregard of the need for compensation – not in monetary terms, since the Cinemateca cannot charge [for admissions, loans, or services at the time], but in actions that should have been foreseen in its projects and that would allow expanding the collection [...]; the misunderstanding that unique (preservation) materials should not leave the collection without supervision […]”. She added that “it is necessary, therefore, to continue to make efforts to change the conception of the public good as something that can be freely available for the achievement of private projects, and for the understanding of the need, still in the elaboration phase, to consult with the Cinemateca on the feasibility of the project in concerning the intended materials and the deadlines necessary for their availability. These are two necessary conditions for planning whose meeting benefit both the requester and the collection”.

In September 2018, former members of the Board issued an Extrajudicial Notification to MinC, requesting the “revocation of acts […] and rules that violate the technical, administrative and financial autonomy ensured in the deed of incorporation of the Cinemateca Brasileira Foundation […], in addition to: 1) The constitution of a new advisory council in compliance with the necessary autonomy of the body; […] 3) Return of the Cinemateca Brasileira to the structure of IPHAN”. The notification also mentions the “SAv’s omission in the face of the [2016] fire […], and that the Cinemateca Brasileira is no longer part of the structure of the Ministry of Culture and has not earned any public positions”.

Cinemateca Brasileira’s Management by the Social Organization

At the time of the Cinemateca Brasileira’s consolidation in the first decade of this century, maintaining its technical staff was a constant challenge. The technicians were hired for projects with specific durations via different forms of hiring.42 This dynamic created fragility and instability in workflows and compromised strategies and structural solutions, in addition to leaving the technical team in vulnerable positions.43 The SO management model would be the desired solution to enable the stabilizing of the technical team’s employment statuses after years of scarcity. Futemma evidenced this hope in an e-mail sent to the ABPA listserv: “This discussion [of the SO management model] has been taking place for eight years, involving MinC, SAv, the Council and the Cinemateca team. We have great expectations that, by the end of this year, a new management model will allow the Cinemateca Brasileira to exercise its full potential in favor of Brazilian audiovisual heritage”.44

The SO management model was the solution deliberated upon after a period of instability among the Cinemateca’s technical staff. It came with the possible preference of a SO created especially for the management of the CB, Pró-Cinemateca, built in 2014 by members of the Council and SAC with the sole purpose of managing the Cinemateca. It would potentially have the participation of professionals from the field in the construction of a Work Plan – the core document for the management itself and one of the selection criteria in the public tender. Pró-Cinemateca qualified for the first tender call, but it could not advance in the second tender call due to a new requirement for previous experience of the institution in the management of public resources. The Pró-Cinemateca itself had no experience, as it had only been created recently. Still, its representatives had spent many years at the Cinemateca’s Council, which, in practice, could have been argued as a more relevant credential than the company’s management history.

Today, following the emergence of controversies surrounding the management of other public entities, cases of corruption, and a series of publications made in the Academy and on the internet, the SO management model is widely questioned.45 It has been shown to be particularly risky for cultural heritage institutions with insufficient government funds, contexts in which essential conservation workflows (often costly and of low visibility) can be overshadowed for the benefit of actions with greater visibility. The elaboration of a work plan without the technical team’s effective participation can compromise its primary objectives. As diagnosed by Fabiana Ferreira:

“Another problem with this tenure is, claiming people are free to raise funds through means other than the State ignores that they also end up at the mercy of the State. Because, in Brazil, there is no tradition of private institutions supporting culture. The private sector in Brazil does not support cultural initiatives. Traditionally, millionaire families and Brazilian corporations do not make donations or investments in cultural equipment, even less for those who do not give visibility to the brand”. (2020, p.110)

In the CB’s case, the management by the SO enabled the CLT (Consolidation of Labor Laws)46 hiring of a good part of the team, whose choice, fortunately, fell to the institution’s coordinators without the intervention of Acerp. However, the technical staff gradually became conditioned to the Acerp guidelines. This conditioning was evident during internal meetings, where it was no longer possible to play an active role in collection prospection47 or to speak on behalf of the institution without Acerp’s consent. Signs of change were perceived in the team’s modes of social interaction in a dystopian way. For example, a camera network to oversee the collection and equipment was installed by Acerp and covered spaces previously used during work breaks. This modern panoptic lookout generated discomfort among us.

Internal courses on technical subjects or on workflows and activities between sectors, which had been held regularly since 2017, were suspended. Fundraising for the Cinemateca was among the actions sought by Acerp, and the usages of the collection and facilities proved to be a quick means to this end, thus generating long periods with a constant flow of production of major events that held varied themes, sometimes apart from the cultural and audiovisual spheres. Since Acerp did not issue the 2018 and 2019 Reports, access to information about these events is not possible to obtain. The absence of the publication of annual Reports is a dangerous indication of the failure of the SO model for the Cinemateca, as they have been essential documents for accountability and transparency of the institution’s management. During the SO period, Acerp issued reports for the Ministry on the performance of Work Plan goals. However, these documents are quite technical and not very informative, in addition to being inaccessible today to the general public. Acerp proposed a Code of Ethics and Conduct for CB employees, presented at an event on company compliance – the sole enunciation of religious beliefs48 was a significant demonstration of the distance between Acerp and the CB’s institutional mission.49 Plus, Acerp’s inability to clear bureaucracies for equipment acquisition for the Lab was evident, which affected work plans that were reliant upon such equipment’s availability. Requests for access to the audiovisual collection by TV Escola for use in their programming became routine, while Acerp meanwhile ignored some work-related needs pointed out by the technical staff. Film programming proposals were negatively impacted by the presence of Acerp. After all, how does one present the idea of a Fassbinder series to a board that made homophobic jokes during small talk before meetings?

The late self-cancellation of CryptoRave’s50 2019 edition by the Cinemateca team for fear of reprisal was symptomatic. An undeniable symbol of the occupation by Acerp was the creation of a new institutional website without the active participation of the CB’s technical staff in editorial decisions. As an example of this fiasco, Acerp implemented a new website without the previous dynamic calendar tool. Resultingly, the new website has a more updated design but is less functional than the previous site had been. Also, Acerp immediately implemented an intermediate logo (‘cinemateca brasileira’ in white on a red background), replacing the 1954 logo which was created by the celebrated designer Alexandre Wollner. Acerp commissioned a new logo design that was presented to the technical staff, and allowed us no time to deliberate as to whether or not we approved of it. The fresh concept and layout were surprisingly similar to the logo of the Curta Cinema - International Short Film Festival in Rio de Janeiro. Acerp is in fact headquartered in Rio de Janeiro and the Cinemateca Brasileira in São Paulo,51 which produced another convoluted aspect: the expenses of transportation, accommodation, and meal tickets for directors, managers, and legal consultants between the two cities, which altogether sum up to a considerable amount. Rather than spend this money on transportation, it could have been invested in the CB itself.

An unquestionable symbol of the SO management model’s failure for the Cinemateca was the dissolution of the Council, constituted of representatives of the government and civil society. The CB’s 1984 legal document of incorporation to the federal government determined the existence of the Council. Acerp, acting without the Council’s input, appointed several directors who had no experience in heritage or preservation fields. This appointment further alienated the technical team who worked to manage the CB. In addition to all of this, the Cinemateca – a historically non-partisan institution – became, through Acerp, the destination of people linked with the extreme right-wing political party of the acting Brazilian president. These people assumed various administrative and communicative positions at the institution without any proven expertise. The newcomers would frequently present the institution’s vaults to visitors without a technician’s due presence, further undermining conservation efforts. The presence of military personnel at the Cinemateca52 and their failed attempt to organize a military film series gained broad reverberations. During the first two years of Acerp’s management (2016-2018), the technical team was autonomous and in control of projects. However, there was a major loss of autonomy in the SO management model from 2018 onwards.

The administrative limbo of ten public servants who were allocated to the institution found themselves in is another important matter. Since the beginning of the SO management, when the CB ceased to have administrative backing under the former SAv/MinC, these people had remained in their positions. Some of them had served at the institution for more than three decades. Before the SO amendment was signed, they were guaranteed that they would not receive losses in their salaries and benefits. However, after the amendment was signed, the governmental understanding changed, and their assignment to Acerp was never made official. Despite this situation, the Ministry instructed these workers to continue with their activities at the Cinemateca. After a year and a half of neglect and contradictory messages, they had to abruptly abandon their functions at the CB to work at the Southeast Ministry’s Regional Office in São Paulo without any infrastructure to welcome them. In addition to this sudden displacement, they were forced to acquiesce to a legal process based on the necessity of returning a bonus earned during the period that they had worked at the CB under the SO administration – a bonus which represented a significant part of their salaries.

Although Acerp assumed the institutional relations more broadly, the Cinemateca’s relationship with FIAF continued to be maintained by Olga Futemma and fellow coordinators, who issued thorough annual reports to FIAF and the prompt inspection of information requested by affiliates. However, between 2016 and 2019, neither Futemma or the coordinators represented the CB at the FIAF congresses held in Bologna, Los Angeles, Prague, or Lausanne.

2020 Crisis

In February 2020, the CB’s off-site facility in Vila Leopoldina was badly affected by a flood from heavy rains and lack of proper management of the storm sewer, combined with the intense pollution of the Pinheiros River, less than half a mile away. The sewage water reached more than a meter in height and destroyed a part of the film and equipment collection, including the last surviving materials of some narrative short and feature-length films, as well as many unique elements of newsreels, advertising materials, and trailers. The Documentation and Research Center assessed the damage such that it was not considered to be significant, since the majority of what had been destroyed was duplicated material. The flood damaged shed facilities and equipment. After thoroughgoing sanitation of the facility by the cleaning team, a part of the technical staff was deployed to clean, organize, and rescue the affected materials. Acerp or SAv did not carry out an emergency plan for the urgent assessment and processing of the site’s audiovisual and equipment collections (which had been the most affected by the flooding), such as hiring an extra technical team temporarily or even granting permission for the obtaining of volunteer work.53 The catastrophe was not immediately reported due to the lack of coordination between SAv and Acerp, and the technical team was not permitted to make news of the flood available to the public. The small team established different shifts in consideration of the high toxicity of the environment and the exhaustive work involved, with their efforts made all the more difficult by the warehouse’s high temperatures without air conditioning and local ventilation.54 Film materials were selected and transferred to the main headquarters for evaluation and processing in the Lab, but the raw film stock was running low. The damage of the audiovisual and equipment collections in the facility, the inaction of SAv and Acerp, the crisis which would subsequently occur, and the interruption of the rescue and research work ultimately makes this flood equivalent in nature to a catastrophe like the Cinemateca’s fires. Per Fabiana Ferreira, such disasters “are a metaphor for the fragility of the making of an audiovisual preservation policy that goes up in flames with each change of Government, of the creation of entities, of new agents” (2020, p.23).

Since the 2013 crisis, the Ministry’s funds have fallen short, which has resulted in smaller teams than were anticipated for the work plans. At the end of 2019, there was yet another crisis, when the then-Minister of Education (MEC) decided not to continue the TV Escola project – the main object of Acerp’s contract with MEC – and did not renew the SO Contract with Acerp. Once the MEC’s main contract was extinguished, all other agreements were also terminated. This is despite the CB-specific amendment ostensibly being valid until 2021. As a result of this termination, the administration of the CB was left adrift. Acerp spent a few months trying to circumvent the decision and to obtain funds from SAv, the Special Secretariat for Culture, and the Ministry of Tourism, but without success. The year 2020 was filled with absurd news of government decisions involving the CB, causing commotion in the filmmaking community and becoming widely covered on media outlets and social networks.55 In April, Acerp stopped paying outsourced companies and technical staff. Former members of the Council launched a manifesto in May.56

The Federal Prosecution Service initiated civil legal action against the Brazilian federal government in the interest of compelling an emergency renewal of the contract with Acerp. By the end of October 2020, the understanding has been a settled situation involving contracting essential services such as security personnel and firefighters. However, the action is still in progress, and the expectation exists for a new decision that will be favorable to the CB. Resistance and protest networks have been formed and strengthened, diffusely, with multiple participants who have narrowed their communication efforts over time: Cinemateca Viva, Cinemateca Acesa, and representatives of the São Paulo Association of Filmmakers (Apaci) - SOS Cinemateca.57 These groups have been active in performing demonstrations on behalf of the Cinemateca and building connections with municipal and federal government representatives. During this time, the CB’s spokesperson has not been the manager or the coordinators, but rather a diffuse representation of employees.58

The technical team continued to work remotely (when possible) soon after the COVID-19 pandemic began and went on strike in June with the Union’s practical assistance. A campaign was then initiated by CB workers to raise funds for colleagues who were left in the most vulnerable situation due to the lack of payed salaries right during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The campaign received numerous contributions from individuals and institutions around the world.59 Direct donations were made directly to the CB, such as one from a Brazilian director who donated a sum for repairing a generator and wished to keep his contribution anonymous. In July, a debate was held in the Chamber of Deputies60 with the presence of government representatives and different players in the audiovisual industry and a number of other civil society members. The discussion served as a symbol of the unprecedented repercussion and engagement around the Cinemateca. In a way, it also highlighted the need for preservationists to ensure that the language and information spoken about the CB was factually accurate.61

There were few instances of direct communication between Acerp’s board of directors and the CB technical staff, and the coordinators were sharing news related to the institution in a sporadic fashion. In June, Acerp’s directors issued an undated statement (undated!) expressing solidarity on “difficulties that everyone is going through,” claiming, “do know that we are doing ... everything that is within our reach”. The statement included the commitment that “as soon as we receive funds from the Federal Government, the first step will be to pay salaries and termination packages” – even though it had already been made explicit that there would be no funds transferred by the government. Considering the lack of resources in 2020 for the Cinemateca, the flood, the crisis arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, remote work, and the suspension of wages and benefits, this statement symbolizes the neglect and disrespect that Acerp showed the CB staff. After handing over the Cinemateca’s keys to the Ministry on August 7,62 Acerp unsurprisingly and abruptly fired all of its and the Cinemateca’s employees without arrears and severance pay.

As noted in the 2020 Gramado Letter (published just after the annual Gramado Film Festival), “after countless phone calls, messages, consultations between the parties and postponements, basic and emergency water and electricity services were guaranteed […]; cleaning services were contracted, although the company is not specialized; maintenance services for climatization equipment were contracted, although the company does not offer the necessary expertise; a small fire brigade composed of two employees and a property surveillance company were hired. However, specialized employees’ primordial work is lacking among the emergency needs, without which the collection will not be preserved, even with the resumption of the basic services described above”.63 Without technical monitoring, the smallest of incidents in the collection areas can hold drastic and irreversible consequences. This is the first time in the history of the Cinemateca that any of its technical staff members have been restricted from entering the institution.

Together with the news of the handover of the Cinemateca’s keys to the Ministry of Tourism, it was made clear that a new SO public tender announcement would soon be launched. This announcement has not yet occurred. There is a budget forecast of R$ 12.5 million [about USD 2.3 million] for the Cinemateca in 2020. If not used this year, this value cannot be added to the sparse R$4 million [about USD 720 thousand] foreseen for 2021. São Paulo councilors from different political parties organized a parliamentary amendments fund for the Cinemateca, with support from Spcine, the predominant audiovisual agency in the city of São Paulo. The deploying of municipal resources towards a federal institution requires an unprecedented legal articulation, which is being made by SAC for the emergency hiring of a small technical body. Today, civil society groups are still active, with an attempt underway to activate entities and continue the mobilization.

It is imperative to create an immediate solution to make a technical team viable in 2020 so that the Cinemateca’s collection does not remain unaccompanied. Furthermore, mechanisms are needed for the continuance of middle and long-term management, in a resilient and sustainable manner that can prove consistent with the need for constant maintenance of the collection and continuance of the technical team. It is considered fundamental to open and create calls for civil service examinations for job positions that could confer the desired stability. As diagnosed in the 2020 Ouro Preto Letter:

“Preservation of cultural heritage is a constitutional duty of the Brazilian State and, therefore, it is necessary to recover the role of the public power in the management of audiovisual heritage institutions, resuming the processes of opening public tenders for job positions and implementing management plans designed together with civil society, a directive provided for in the 1980 UNESCO Recommendation for the Safeguarding and Preservation of Moving Images”

An idea that has appeared throughout numerous online discussions is the return of CB to a federal government heritage institution such as IBRAM or IPHAN, to which the CB was linked until 2003, when it became the responsibility of SAv. This link to IPHAN provided continuity for the CB in the early 1990s when the federal government promoted the dismantling of cinema and institutional policies. IBRAM is an autonomous organization linked to the Ministry of Tourism, which covers thirty national museums.

Legal Deposit and the Audiovisual Industry

Despite the unquestionable duty of the State (and its evident neglect), I emphasize that interest and concern about an effective preservation policy must be seen as relevant by all sections of the audiovisual industry. We must challenge the generally held assumption that the “symbolic asset of memory is inferior to the symbolic asset of a feature film shown in shopping mall cinema venues” (Ferreira, 2020, p.111). This value was built, for decades, by the industry itself. It is possible that the FSA’s prosperity (and the increase in investments in development, production, distribution, and exhibition), together with the inaction of the audiovisual industry concerning preservation, are directly related to the dimension of the current Brazilian audiovisual heritage crisis. ABPA has repeatedly pleaded for seats on the Superior Council of Cinema and on the FSA Fund Committee, without success. In the 2018 CineOP debate “Frontiers between Industry, Market, and Archives – Content, Promotion and Regulation”, a representative of the FSA Fund Committee suggested for preservationists to search for a different financing source for preservation, distinct from the FSA. When a professional raises such a possibility (and his attitude is common among producers), he does so without understanding the importance of preservation for the entire industry, nor his role in defending the Cinemateca and audiovisual heritage policies. Let this defense be made from the personalized perspective, considering that some of his assets may be held at the Cinemateca: footage for his next film as a producer, the origins of his debut feature, or his family’s home movies. The Cinemateca’s activities in discussions, publications, forums, and technology research could also benefit him in other ways. As Paulo Emílio wrote, “You can’t make good cinema without a cinematographic culture, and a living culture simultaneously requires knowledge of the past, an understanding of the present, and a perspective for the future. Those who confuse the action of cinematheques with nostalgia are mistaken” (1982, p.96). The production industry grumbled64 when debating the need for investments to deal with the giant backlog of audiovisual works which need to be preserved in order to serve the production industry. Such preservation benefits this industry as they are then able to commercially utilize the collections. The business model does not close until we have a massive investment to deal with decades of setbacks and stagnation. I grumble back with this chart:65

In April 2017, the FSA’s 2017 Annual Investment Plan66 comprised R$ 10.5 million [about USD 1.9 million] for the Cinemateca Brasileira. This announced value for the CB was equivalent to 1.4% of the total announced in the document. The amount was never paid, with the justification that the non-refundable funds67 ran out. In May 2018, the FSA 2018 Annual Investment Plan68 appointed R$ 23.375 million [about USD 4.1 million] for investments in Preservation. In December of that year, SAv published a tender for Restoration and Digitization of Audiovisual Content. These were funds that allegedly held a return on investments made by audiovisual companies in restoration or digitization. A preservationist workgroup and CB technicians aided in construction of the document and the digitization and restoration technical guidelines. From the preservationist’s perspective, the tender was intended only for producers with a distribution bias and held the preservation aspect as secondary. The current government suspended the tender about four months after its publication. Therefore, out of a possible sum totaling over R$ 4.5 billion69 [about USD 801 million], no FSA funds whatsoever were actually invested in preservation between 2008 and 2018.

Currently, the Cinemateca Brasileira is the onlyx institution nominated to accept Legal Deposit materials. Since 2016, Ancine has invested no more than R$ 2 million [about USD 356 thousand] in hiring a technical team to analyze materials. New technicians must be hired specially for this, as the Legal Deposit workflow mobilizes several sectors and technicians. Over the years, the CB reported a high failure rate of materials analyzed. According to Gomes (2020), “one of the main causes seems to be the great distance and little information from directors/producers about, in a broad way, the role of an audiovisual archive, and more specifically, the principles of the Legal Deposit”. The expertise in analysis of materials without funds for preserving the Legal Deposit collection can be metaphorically considered through the gesture of slashing one’s own throat. The analyzed materials are left inert on shelves in an air-conditioned vault at the mercy of the famous “silent death”.70 The industry must take part in actions towards the improvement of approval rates and creating conditions for preserving digital-born materials within the scope of the Legal Deposit. Broadly, the narrative and the struggle for policies related to audiovisual heritage must also be formulated and driven from within the industry.

The panorama of the Cinemateca presented in the 2020 Gramado Letter is very significant, with several associations listed as signatories, including other film archives, professional TV networks, and audiovisual companies. A positive sign was a discussion about the crisis during the ABC Week of 2020 (organized by the Brazilian Cinematography Association [ABC]), which is considered to be one of Brazil’s most significant events devoted to audiovisual production. But we still need tremendous action to get closer towards recognizing that this crisis at the Cinemateca Brasileira must remain a concern for the entire industry.

The 2020 Ouro Preto Letter highlights, among many urgent matters, the implementation of a national policy for the area of cultural preservation. The letter outlines some of challenges which will be faced, such as “to claim the creation of mechanisms, to expand the offerings of Brazilian audiovisual works in the catalogs of streaming platforms, with the guarantee of inclusion of works from different periods that can allow access to the vast Brazilian audiovisual heritage”. What would be the suggestion proposed by Netflix (used here as a platform model), for example, regarding the need for investment in Brazilian audiovisual heritage? Such an investment would only provide an opportunity for company-improvement, made viable by Netflix’s presence among the 12 companies that profited most during the current pandemic.The proposal is not so absurd, considering that the company’s Brazilian wing created a R$ 5 million [about USD 891 thousand] emergency fund for the Brazilian audiovisual industry due to the recess in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.71 The availability of older works on streaming platforms is also a point of concern in the United States.72 In general, Brazilian producers do not have resources for digitizing older titles in ways capable of meeting the platform’s technical parameters and, need to potentially spend whatever resources they do have on lawyers who can help them with rights clearances.73 So, how about the platform launches an investment line for non-contemporary works? This idea would be contemplated by the 2018 SAv/MinC/FSA tender for “Restoration and Digitization of Audiovisual Content”, suspended in 2019. The strength of the audiovisual heritage institutions also would benefit the streaming platforms themselves in the middle term, considering the strong contemporary trend of documentaries based in archival images.74 As an illustration, there is a significant number of U.S. documentaries available on Netflix Brasil that use archival images to build their narratives such as Wild Wild Country (2018), Disclosure (2020), the documentary series Remastered (2018), and Explained (2018). However, there are comparatively few Brazilian films and series that feature archival images to this extent, one exception being Thiago Mattar’s Taking Iacanga (2019).

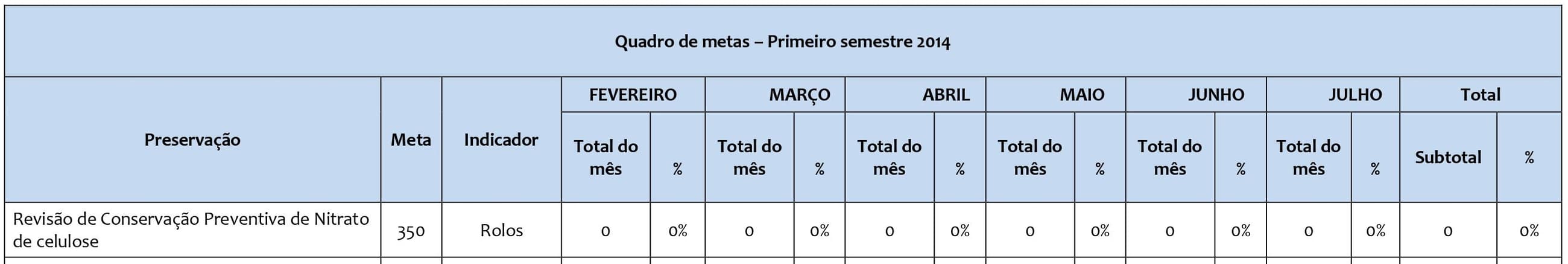

In addition to the CB Lab’s conservation of its collection, I call attention to the confection of new film prints and digital copies, such as those pertaining to the collection Classics and Rarities of Brazilian Cinema, (which was founded in 2007 and underwent its fourth edition in 2016) and those made in celebration of the annual International Day of Audiovisual Heritage. As a means of registration, I highlight the 35mm and digital prints made in 2016, as contained in the Report.75

Creating new 35 mm prints is one of the crucial roles of a film archive with a photochemical lab, as it is vital to provide an experience in line with the original screening format of a film. Considering how digital exists for the sake of broader circulation, digital access files are made in different formats. In the context of the CB, the effort to digitize films made on film would be carried out more fully with some form of pre-established screening event, ideally with formal curatorship and due contextualization for the works. Currently, the clearest path to digital diffusion of CB assets comes via the institution’s own online Cultural Content Bank (BCC).76

Rafael de Luna Freire’s Cinelimite article "Ten Brazilian Films that Remain in the Shadows due to Poor Accessibility" discussed digital inaccessibility for a combination of canonical titles and rarities throughout the history of Brazilian cinema. In addition to creating effective digital access actions, it is crucial to assess whether original film materials exist beyond imminent risk or whether they in fact require urgent preservation or duplication measures. Rafael de Luna’s list evoked the text “Brazilian films considered lost (or about to be lost)”, published in 2001 in the now-extinct Web magazine Contracampo.77

Differently, the 2001 list was about the existence or loss of preservation materials. In addition to some titles that were eventually lost, others had their (known) unique materials deteriorated to the point of making lab processing unfeasible. In light of the Cinemateca Brasileira crises and the paralysis of research work, preservation actions, and laboratory processing, the act of updating the list made by Hernani Heffner and Ruy Gardnier at that time would be of tragic scope. It would be a national institution’s role to make this list public. Besides remaining accountable to Brazilian society about its audiovisual heritage, this work could also prove to be a strategy for locating previously unknown materials held at other institutions and private collectors both in Brazil and worldwide. Yet, what about the many other films and audiovisual records that have escaped such inquiries and remain ostracized? How many films exist today whose only surviving materials are believed to be incomplete and severely deteriorated prints in inferior gauges? How many Brazilian audiovisual records have we lost?

Conclusion

“If we lose the past, we will live in an Orwellian world of the perpetual present. So, where anybody that controls what’s currently being put out there will be able to say what it’s true and what is not. And this is a dreadful world; we don't want to live in that world.”Brewster Kahle (2014, interview for Digital Amnesia, documentary by the Dutch VPRO)

“Knowledge is effective only when it is shared.”Hernani Heffner (2001, in a hallway conversation at the Cinemateca do MAM in Rio de Janeiro)

Digital audiovisual records have served as crucial tools in the fight for human rights in all national corners. They include records of things such as forced evictions, occupations of cultural or educational sites as a form of protest, demonstrations, invasions of communities by police forces (with high homicide rates among local populations, including children and young people), acts of environmental devastation fostered by the current government, struggles for native people rights and the demarcation of native lands, and crimes against native peoples. These audiovisual registers also function as tools for black empowerment and anti-racist movements, for the emancipation and affirmation of women for opportunities, and against structural sexism. With a profusion of creative talents and narratives, social networks gather the most distinguished cultural indexes of this time. In Brazil, in general, these network’s images remain outside the scope of prospection by Brazilian institutions, with the discussion around their archiving and incorporation within the scope of Brazilian audiovisual heritage still proceeding in a merely tentative fashion. From the preservation perspective, aside from all the challenges inherent to digital data preservation,78 ephemerality exists due to the corporate practices of social networks (which wipe content according to their terms of service).

Social media uses persuasive technology mechanisms to drive individual’s behaviors. Algorithms can give credibility to the untrue, boost flat-earth theory, and put #StopFakeNewsAboutAmazon as a trending topic on Twitter. At the same time, ecocide is loose, and the whole world watches as flames engulf the Amazon, the Cerrado, the Pantanal, and other Brazilian national parks.79 The quantum computer Rehoboam80 is an allegory of the now, in a narrative made explicit by Shoshana Zuboff in her book “Surveillance Capitalism”. We observed successive electoral victories by ultra-right political parties and movements with growing levels of terror and violence. The circulation of fake news on social media has increased the destructive power of Covid-19. Counter-information, deep fake, and fake news robots are connected to the world described by Brewster Kahle, founder of Internet Archive, quoted above. We can lose the past and the present due to frailties inherent in today’s sources of information, with their potential for manipulation and misinformation.81 When the current Brazilian president was a deputy, during the congressional voting process held during the impeachment trial of President Dilma Rousseff, he voted for the memory of the military dictatorship’s greatest torturer, who led the former “Presidenta” torture sessions. At the Cinemateca, we failed to frequently screen and watch the anti-dictatorship films Case of the Naves Brothers (1967, Luis Sérgio Person), Iracema: An Amazonian Transaction (1974, Jorge Bodansky/Orlando Senna), Tarumã (1975, Mário Kuperman), They Don’t Wear Black Tie (1981, Leon Hirszman), Go Ahead, Brazil! (1982, Roberto Farias), Twenty Years Later (1984, Eduardo Coutinho), How Nice to See You Alive (1989, Lúcia Murat), Friendly Fire (1998, Beto Brant), and Citizen Boilesen (2009, Chaim Litewski),82 in order to make it impossible to trivialize his actions in the Chamber of Deputies and make it such that no woman would vote for him for president two years afterward. Now we cannot fail to preserve these films and those that have come after, such as Orestes (2015, Rodrigo Siqueira), Pastor Cláudio (2017, Beth Formaggini) and Maiden’s Tower (2019, Susanna Lira).

A significant portion of the Brazilian audiovisual heritage has already been lost over the past century. In addition to recurring fires that destroyed collections of early Brazilian cinema, there have been diverse waves of destruction throughout film history (of short films through the consolidation of the feature as a market format, to silent films after the emergence of talkies, to the replacement of nitrate by acetate), many collections have been dispersed, dismantled, and concealed. Numerous works that came to the film archives arrived in an already feeble state. Still, the delay in recognizing the importance of audiovisual heritage, the absence of public policies for its management, and the oscillation of funding to heritage institutions have led to further losses. With the advent of digital, there is an escalated move towards preserving both what is currently being prospected and what lies outside the current prospection scope. The Cinemateca’s current crisis is severe, and it demands urgent measures from public authorities and the audiovisual industry. Despite the government’s destructive power and the ongoing paralysis of the work, I would like to end with an optimistic tone, one that has been encouraged by many online discussions, articulations, and increasing support about audiovisual preservation in Brazil. Many have advocated for their belief in the Cinemateca’s potential to promote debates and screenings, grant access to the most forgotten collections, provide a space for research, offer a visual reference for the past, and subsidize technological research. People believe in its capacity to captivate children and young audiences with the big screen, present pre-cinema and audiovisual technologies in a museum, and engage the institution’s neighborhood and surrounding community. All of these potentialities of the institution, in addition to numerous other creative uses of its collection and the tools that we might be able to use in the future, have been marred by the successive crises and ever increasing backlog. As a result, we have seen the acceleration of the collection’s deterioration, and limitation of the institution’s reach. It has become even more evident over time that the Cinemateca has been included within a macro-project of the devastation of Brazilian culture and heritage, and its importance as a force for reacting against this project therefore grows larger and larger.

Thanks to Aaron Cutler and William Plotnick for the thorough review.

1. The Ministry of Culture was abolished on the first day of the current government, then initially incorporated into the Ministry of Citizenship and, later, to the Ministry of Tourism. So far, the Special Secretariat for Culture has had five incumbents without proven expertise. Other cultural heritage institutions are experiencing acute crises, such as the Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa and the Centro Técnico Audiovisual (CTAv). The Brazilian Film Agency (Ancine) did not transfer funds already committed to the Cinemateca Brasileira and did not issue new film production tenders. It is noteworthy that the Federal Constitution which governs Brazilian democracy claims the “State will guarantee to everyone the full exercise of cultural rights and access to the sources of national culture and will support and encourage the valorization and diffusion of cultural manifestations” (Art. 215). They add that, “the public power, with the collaboration of the community, will promote and protect Brazilian cultural heritage” (Art. 216).

2. From 2016 to 2020, I worked in the Film Preservation department at the Cinemateca Brasileira. I share personal views based on this experience, with an emphasis on the department’s activities.

3. Eng: “The Cinemateca Brasileira and public policies for the preservation of audiovisual heritage in Brazil”.

4. CineOP 15 years: Live with Hernani Heffner, Cinemateca do MAM manager. September 2020. https://www.instagram.com/tv/CEC_cUVlbK6. Acesso em: 18 set. 2020.

5. Through the Ministry of Culture’s policy of decentralization, development and production programs were created with quotas for states which habitually have been restricted from investing in audiovisual production. Also, a policy has been put in place that covers low-budget projects and quotas for new directors, female filmmakers, and native people.

6. Regulated in 2007, the FSA is fed by the Contribution to the Development of a National Film Industry (Condecine) and a tax collected from all media distributions systems. These funds are then invested in new productions mainly in cinema, television and electronic games. From 2008 to 2018, a total of approximately R$ 4.5 billion was invested [about USD $713 million].

7. An emblematic example of this dynamic occurred in 2008, with the presence of the Executive Director of the Cinemateca Brasileira at the 3rd annual CineOP. The theme of CineOP that year was National Audiovisual Preservation Policy: Needs and challenges. Throughout the event, the Executive Director took a firm stand on opposing the articulation of other audiovisual heritage institutions with the Ministry of Culture’s representatives, and the creation of the Brazilian Association of Audiovisual Preservation (ABPA).

8. Among the proposals of the 1979 Symposium on Cinema and Memory in Brazil was, “The creation and promotion of regional centers of cinematographic culture constituted by production units and by film libraries (archives of copies of films), with the basic function of prospecting, research and dissemination of the Brazilian collection [… and] the establishment of an [national] inventory” (1981, 67). Laura Bezerra stated that the “creation of a program to boost filmographies that, despite not having implemented systematic and comprehensive actions, allocated resources for some sectorial actions” (2014, 120). Decentralization is necessary, considering the country’s continental nature and cultural plurality, besides being technically susceptible to disasters.

9. CineOP was created in 2006 and has become the main forum for discussions and articulations on audiovisual heritage and education in Brazil. Each year the Ouro Preto Letter is issued by the meeting’s participants, with alerts and proposals for the audio-visual heritage field.

10. ABPA is an association of film preservation professionals, regardless of their formal occupation. ABPA has worked in favor of developing new and better film preservation policies, the promotion of audiovisual heritage, and the translation and publication of technical film preservation texts. In 2016, ABPA created the PNPA, a document that contains diagnoses and proposals for actions and policies within the field of audiovisual preservation. https://abpanet.org/

11. The Council’s central role is to work to help develop the Cinemateca. Its members are representatives of the public sphere and individuals from civil society who are linked to the cinema or cultural heritage industries. Dismally, men have been predominant among council members over the years.

12. Currently, this theater is called Cinesala. http://www.cinesala.com.br/cinesala. Acesso em: 4 ago. 2020.

13. The original slaughterhouse had its activities closed in 1927. The space was then used as a deposit for the city hall’s lighting equipment.

14. The Brazilian Cinematographic Census project was based on the idea of Gilberto Gil, musician and then a member of the cultural advisory board of BR Distribuidora. Gil would later become the Minister of Culture from 2003 to 2008.

15. State company Petrobras – linked to providing energy, gas, and oil in Brazil – boosted the production, distribution, exhibition, preservation, and restoration of Brazilian cinema.

16. In collaboration with the CB, the appraisal project was also carried out at the Cinemateca do MAM (Museum of Modern Art) in Rio de Janeiro. The project involved the (unprecedented) inventory of the Cinemateca do MAM collection with deteriorated materials sent to the CB’s lab. The Museum director determined, arbitrarily, that the Cinemateca could not maintain its audiovisual collection (after the inventory was made). As a result, the National Archive (in Rio de Janeiro) and the CB each received parts of the collection. Rather than having them sent to Rio de Janeiro, some film material owners chose to keep their assets with them, often in inappropriate places. That was one of the Cinemateca’s biggest crises, which is historically relevant for Brazilian cinema (especially for the Cinema Novo movement) and the audiovisual preservation area. The Cinemateca do MAM was directed by Cosme Alves Netto, who had a special connection with international institutions. Hernani Heffner joined the institution in 1996. In 2020, the Cinemateca do MAM underwent a consolidation, with a new building for the film collection and some structural changes in the Museum’s direction.

17. According to Souza, the Brazilian Filmography was started by Caio Scheiby on paper cards, and, in the 1980s, four notebooks were published with records of films produced until 1930 (2009, p.259). Currently, according to the CB’s website, “it contains information on approximately 42 thousand titles from all periods of national cinematography and the most recent and widest audiovisual production, whether short, medium or feature films; newsreels; advertising, institutional or domestic films; and serial works (for internet and television), with links to records in the database of posters and references to sources used and consulted”. Filmografia Brasileira. August 2020. Available at: https://bases.cinemateca.org.br/cgi-bin/wxis.exe/iah/?IsisScript=iah/iah.xis&base=FILMOGRAFIA&lang=p.