Introduction

My professional entry into the field of film preservation coincided with the emergence of digital restoration in Brazil. I began working within film archives in the year 2000. Being around archives at that time allowed me to witness the impact that digital technology was having on the still nascent field of digital film restoration. It was my desire to investigate my own early experiences as a film preservationist, systematize them, turn them into an object of study, and to contribute to a wider discussion on film restoration, that prompted me to begin doctoral research at the University of São Paulo in 2016. I finished this research at the end of 2020,1 focusing my dissertation on film restoration in Brazil and the incorporation of digital restoration technology in the 21st century. The research I conducted had two dimensions: on one hand, it included my professional experiences, and on the other, my interest in considering the historical process of film restoration in Brazil from technical, aesthetic and ethical perspectives. A small excerpt from this work will be addressed in this article, where I will present, in general terms, a historical background of film restoration in Brazil, a brief overview on the trajectory of the digital restoration field since the year 2000 and highlight some historical milestones since its early beginnings.

Significance of the Year 2000

Over the last two decades, the field of audiovisual preservation has undergone profound changes. One of the evidences of this transformation can be found in the increasing amount of research being conducted on the topic of film preservation and its various aspects. The incorporation of digital technology within the film restoration process allowed the field to gain more prominence both in terms of practical skills and as an academic discipline. As a result, scholars have attempted to theoretically define it through deeper analysis of its many complex elements. The international bibliography on film preservation has also grown considerably since the 2000s, including welcome contributions from Brazilian researchers and scholars. Although in-depth film restoration research is still not very common in Brazil, the emergence of recent prominent writings on this topic and related issues proves that there is serious interest in the topic and in audiovisual preservation as an academic discipline.

From the late 1990s to the mid 2000s, digital film restoration tools were introduced and disseminated among major film archives, with financial support from big film production companies.2 At first, due to the prohibitive costs for most institutions and archives, these tools were only utilized occasionally. However, technological advancements allowed them to become more affordable for non-commercial projects and more widely adopted into the film restoration process along the first decade of 2000s.

Digital technology was incorporated into the restoration workflow in Brazil in the early 21st century, similar to what was taking place in some European countries and in the United States. Up until that point in time, each stage of the restoration process was photochemical. Film restorers were utilizing analog machines that had been used for years in commercial film laboratories and the technical staff behind most restoration projects were predominantly trained while working for these laboratories. With the arrival of digital tools, interventions into the restoration process began to be carried out by computers and professionals with new skills. These new restorers were well versed in digital restoration software and computer-based technology and had different professional backgrounds than the technicians who had only previously worked in film laboratories. Before providing a further analysis of the digital restoration field in Brazil, it is first necessary to present an overview of the history of Brazilian film laboratories.

Film Laboratories in Brazil

During the first few decades of filmmaking in Brazil, most of the small film production companies had their own laboratories. It is likely that these laboratories used similar tools to still photography laboratories. In the chain of processing photochemical material, the negative is first developed and then copied to a positive print, resulting in projection prints. In the 1910s, Alberto Botelho’s film laboratory took the first steps toward standardizing these procedures with above-average results. Consequently, their lab managed to create better film prints than what had previously been possible in Brazil. There are references to other laboratories of the time. For example, companies such as José and Victor del Picchia’s Independência Film and Paulo Benedetti Filmes had laboratories and processed titles such as Braza Dormida (Mauro, 1928), Barro Humano (Gonzaga, 1929) and Limite (Peixoto, 1931). A landmark moment for the film processing field occurred in the late 1920s, when Hungarian photographers and laboratory professionals Adalberto Kemeny and Rudolf Lustig relocated to Brazil.3 Kemeny and Lustig would go on to buy the Independência Film Laboratory and turn it into Rex Laboratories, which remained active until the 1970s. The technical knowledge that these Hungarian immigrants brought to Brazil allowed greater general control of the necessary parameters for processing film, such as temperature and time control, being responsible for improvements in the technical quality of Brazilian materials.

The transition to sound cinema in the 1930s made laboratory processing even more complex and progressively caused the closure of small laboratories from the silent period. Regardless of these newfound challenges in film processing, the production company Cinédia, founded in 1930 by Adhemar Gonzaga, built its own laboratory in that decade.

The Cinédia laboratory operated with many setbacks until the end of the 1940s, a particularly difficult period for the company. The context of World War II only exacerbated Cinédia's difficulties, even causing them to momentarily shut down their operations at the end of 1941. In March 1942, the Cinédia studios reopened for the filming of Orson Welles’s It's All True, but only fully resumed productions the following year. The disastrous effects caused by the war, such as the lack of film stock and chemicals for processing films, was felt by Cinédia throughout the decade. The toll of the war on Cinédia culminated in their dismantling in 1949, when Adhemar Gonzaga decided to dispose of the laboratory film equipment. In 1951, Gonzaga interrupted Cinédia's activities and sold part of the studio grounds in order to liquidate all the company's financial commitments. The laboratory was subsequently disassembled and its productions halted.

A historical milestone for film restoration in Brazil particularly relevant to this discussion was the creation of the only existing restoration laboratory in a Brazilian film archive. The Cinemateca Brasileira Film Laboratory was created in 1976 from the acquisition of equipment and parts discarded by the formerly-named Líder Cinelaboratórios,4 a company from Rio de Janeiro that had recently acquired Rex Laboratories with the purpose of expanding its business to São Paulo. This acquisition began after Líder Cinelaboratórios was convinced that the Cinemateca Brasileira would not be a market competitor for them given their non-profit cultural mission. From then on, an informal partnership was established, and Líder began to periodically notify the archive whenever old equipment was discarded.

Carlos Augusto Calil, who was leading the Preservation Department of the Cinemateca Brasileira at the time, managed this acquisition process. His sense of opportunity was essential to the success of the undertaking. Calil had the insight to take advantage of a singular moment - the discarding of the old Rex laboratories machinery. Once the new owners of Rex laboratories began to modernize their lab with new technology, they decided to dispose of their older (but still functional) machinery. Calil was then able to purchase this machinery at discounted prices as a means of bolstering the infrastructure of the Cinemateca's laboratory.

While the old laboratory machinery was being implemented at the Cinemateca Brasileira, Calil had the opportunity to attend the second Summer course organized by FIAF (International Federation of Film Archives) at the Staatlichesfilmarchiv (Film Archive of the German Democratic Republic). This course mainly addressed issues related to the conservation and restoration of films and it was very important for Brazilian professionals. During this course, Calil had access to publications on film documentation and cataloguing which had not yet been published in Brazil, materials that he would go on to share with his colleagues at the Cinemateca Brasileira. This ensured that the knowledge of the film preservation methods being used in foreign institutions would be shared and applied by Brazilian film preservationists in their own work. However, one of the major lessons that Calil learned was that the solution to Brazil’s film preservation problems would have to be invented and developed by Brazilians. This newfound understanding came to Calil from what is now a well-known story in the Brazilian audiovisual preservation community. Calil recounts that Hans Karnstädt, the person in charge of the conservation and restoration laboratory of Staatlichesfilmarchiv, was asked about proper treatment for nitrate films that have become sticky. Karnstädt was surprised with the question and answered that he had never seen any material in such condition. There are reasons for this can be pointed out: as Germany has a cold climate, and because their cultural institutions are financially stable (allowing the maintenance of adequate levels of temperature and humidity in the vaults), they never had to worry about scenarios where a large portion of their collections had undergone severe stages of degradation. But in Brazil, due to the hot climate and the chronic financial instability, sticky nitrate and acetate films were (and still are) a far more common occurrence. Although this situation happened four decades ago, the problems faced by Brazilian film archives and film preservationists have not changed substantially. The conservation conditions of most of the country's audiovisual heritage pose specific problems that only preservationists who have experience working in Brazil can solve.

Digital Film Restoration in Brazil: The Birth and the Rapid Decay of a Field

It was effectively at the end of May 1977 that the Cinemateca Brasileira Restoration Laboratory began duplication and restoration activities. One of the central figures for this was João Sócrates de Oliveira,5 a trained architect who entered the institution without previous experience in cinema, who went on to become an internationally renowned film restorer.

Between the 1970s and 2000s, film restoration projects in Brazil were mainly headed by film archives and carried out in partnership with commercial laboratories or by the Cinemateca Brasileira laboratory. The 2000s represented the growth of public investments in film preservation and the realization of a significant number of Brazilian film restoration projects. During this period, specific emphasis was given to the restoration of the titles of Cinema Novo filmmakers through projects led by their heirs. A few years later, in 2007 and 2009, Petrobras invested in two public calls for restoration coordinated by the Cinemateca Brasileira, attesting, albeit fleetingly, a more active role of the State in promoting and sponsoring film preservation.

At the turn of the millennium, in 1996, digital technology was used for the first time in Brazil during the restoration process of O ébrio (Gilda de Abreu, 1946), a Cinédia production. Despite the fact that O ébrio had its image photochemically restored, the restoration process included a hybrid procedure for sound, mixing photochemical and digital elements. The re-release of O ébrio had been considered since the mid-1990s, as 1996 marked the fifty-year anniversary of its first screening. In March of that year, Cinédia proposed the restoration project of what would have been the original version of the film to Riofilme,6 including its commercial re-release at the end of the process. One of the priorities of this project was ensuring that the film would return to the cinemas, which may be why this restoration project was presented to a distributor. By establishing a process where a newly restored film would be attached to a distributor, the restoration and exhibition of O Ébrio would impact other restoration projects that followed a similar path. In 2002, Riofilme also carried out the digital reformatting and the re-release of another classic Brazilian title, Black God, White Devil (Rocha, 1964).

It was in 2003 that a project which can effectively be considered a milestone for digital film restoration in Brazil began: the restoration of the complete works of Joaquim Pedro de Andrade. This restoration project was realized by his daughters Alice and Maria, and his son Antonio de Andrade. The restoration of Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s complete filmography was a pioneering initiative in the use of 2K digital resolution technology in Brazil. At that time, this kind of technology was mainly being used for the digital intermediation stages performed during post-production for contemporary films. Therefore, this was the first time that a Brazilian restoration project employed this tool. The restoration of Andrade’s filmography represents a definitive milestone for the preservation field in Brazil, as it led to a major technological update for the Restoration Laboratory of the Cinemateca Brasileira. In addition to this update of the Cinemateca lab, the Joaquim Pedro project led to the creation of the Restoration Center at Teleimage, an audiovisual post-production company in São Paulo.

The pioneering initiative of using 2K resolution, and the scope of the project (to digitally restore the complete works of a filmmaker), made it possible for film restoration methodology to be practiced and improved by the archivists and technicians who were working on the project. As it was still an emerging field, the need for preservationists to gain experience with digital restoration tools was essential. After all, making a 2K digital restoration in Brazil was new for everyone involved, so this project represented a great challenge. It was around this time, precisely because of projects like Joaquim Pedro's, that many departments inside commercial post-production and finishing companies were created to exclusively focus on digitally restoring films. Mega Studios and Teleimage, both in São Paulo, and Labocine in Rio de Janeiro were the major companies that were concentrating on digital restoration during that time.

Since 2000, Mega Studios7 has been investing in technological machinery, focusing on the acquisition of digital intermediation equipment. In 2001, they acquired a workstation called Restore, which consisted of a film restoration software built into an exclusive computer for the restoration process. This equipment, manufactured by the North-American company Da Vinci Systems (a pioneer in digital post-production equipment), cost $ 380,000 (about R$ 760,000 at the time). The station did not have the capacity to digitize. Instead, the materials had to be previously digitized by another machine (such as a telecine) in order to be used at the station. Because of this need for previous digitization, the cost of the entire restoration process was very high for Brazilian film archives at that time, leading to a situation where the post-production companies with larger budgets became primarily responsible for introducing restoration technology in Brazil.

Teleimage debuted its Restoration Department with the film Pelé Eterno (Aníbal Massaini Neto, 2004), digitally correcting part of the archival footage in the documentary. This project took about five years to be completed and demanded a lot of work from the restorers. It was only after completing their first restoration that Teleimage decided to expand their restoration division with the digital restoration of Joaquim Pedro de Andrade's films.

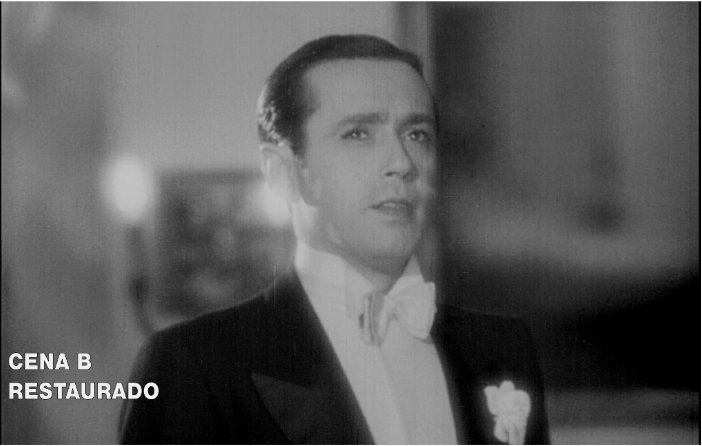

Overall, Labocine’s experience with digital preservation was different to that of Teleimage and Mega Studios. However, it was similar in the sense that its restoration sector began by offering digital intermediation services. Labocine, Teleimage and Mega Studios used their existing structure as a basis for the inclusion of technology destined for the digital restoration of films. That is, they bought specific restoration software, computers with greater processing capacity, and servers with adequate storage capacity. However, instead of investing its time in restoring the works of renowned Cinema Novo filmmakers, Labocine decided to digitally restore Bonequinha de seda, a film made in 1936 by Oduvaldo Viana. Bonequinha de seda was produced by Cinédia, a long-time partner of Labocine, which may have been the main reason why Labocine was interested in restoring the film. Restoring Bonequinha de seda presented the opportunity for Labocine to join an expanding national film restoration market. Also, restoring Bonequinha de seda as their first project, a work made almost 80 years ago, would allow them to stand out from other companies. However, the Bonequinha de seda restoration took much more time than what was initially expected. The restoration of the film, which included photochemical and digital tools, began in 2006 and took about seven years to be completed. The protracted length of the process was due to work interruptions which were caused by technical difficulties and the limited amount of funds available for the project.8 Unlike Mega Studios and Teleimage, Labocine did not have the volume of financial resources that a restoration project composed of several titles would have.9 While the restorations of the Glauber Rocha Collection and Joaquim Pedro’s filmography were well funded, the restoration of a single title made Labocine count on smaller investments. This meant that there were fewer professionals who were exclusively dedicated to the project, less equipment, and slower speed in the execution of the work. Despite the many challenges that this project faced, the effort to restore Bonequinha de seda was worthwhile due to the invaluable digital restoration experience that the technicians accumulated throughout the process.

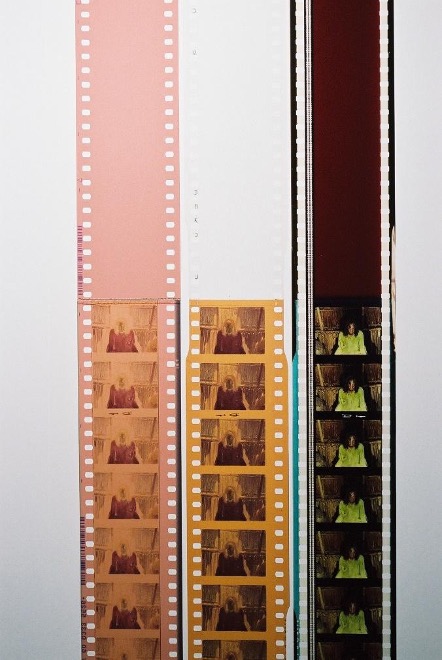

The restoration of Bonequinha de seda ended up revealing the intrinsic limitations of new digital tools when dealing with scratches and abrasions that were incorporated photographically into the image (as shown below). The effectiveness of the Diamant restoration software (used in this process) during the first stages of digital treatment was minimal. This was because the tool could not locate the photographically incorporated scratches and abrasions that had become part of the image. Therefore, the first stages of digitally treating Bonequinha de seda revealed the inherent limitations of digital tools in fixing this type of damage. Also, after an attempt to use these digital tools to partially stabilize frames, the end product was even worse. The resulting creation presented numerous artifacts and the worsening of some of the photographically incorporated deformations.

Exhibiting samples of the work and consulting with specialists at international events revealed that the initially adopted procedures by the technicians in digitally restoring Bonequinha de seda were correct. However, the ability of the restoration software to deal with the damage presented on the film was not satisfactory. As a result, permanent communication was established between Labocine and the Diamant software developer company, HS-Art. Communicating the problems experienced in the Bonequinha de seda restoration made it possible for HS-Art to develop specific improvements to the software that would allow it to clean up the scratches and abrasions on the digital images.10

This story11 demonstrates that foreign digital restoration tools such as Diamant cannot completely respond to the specificity of the deterioration problems presented within Brazilian films.12 Because of this, establishing partnerships with restoration laboratories and software manufacturers is especially important for small projects that deal with materials in advanced stages of deterioration. In this sense, the idea of having a restoration laboratory in a film archive (such as at the Cinemateca Brasileira) is a strategic option, since a commercial laboratory will always aim at projects that are financially profitable.

The global incorporation of digital intermediation as part of the audiovisual post-production process in the mid-2000s seemed to bring enormous benefits for the field of film restoration. As digital intermediation became less expensive, it was widely adopted in the restoration procedures and subsequently lead to the development of new digital restoration tools and the area itself. Given the restoration projects that were being carried out since the turn of the millennium, Brazil appeared to be following a similar path of development in the restoration field to the rest of the world. However, unfortunately, the field of digital film restoration started to regress in 2010. In that year, due to a lack of funding to restoration projects, restoration departments such as the one at Mega Studios began to close. What was once considered a widening market soon became a niche service.

From mid-2010, the widespread adoption of digital technology in film production, distribution, and exhibition has led to a decrease of financial resources being invested into Brazilian film laboratories. Prior to that point, the major sources of income for these film laboratories had been making prints of foreign films to be distributed throughout Brazil. This is because it was mandatory that foreign films being released in Brazilian movie theaters produced their 35mm projection prints in Brazil. There is no denying that companies such as Labocine, Teleimage and Mega Studios have shown to be important partners of the previously mentioned restoration projects. But they were also commercial companies, primarily interested in maintaining a profit. The companies which had film laboratories, such as Labocine, severely diminished its profit margins with the decrease and later interruption in the production of 35mm film prints throughout the 2010s.

The volume of public investments in film restoration (and in audiovisual preservation in general) drastically reduced from 2011 onwards, and this has generated harmful consequences for the field. The first notable consequence occurred in 2015 after the Teleimage Restoration Center closed and the company dismissed its staff. Further, the consolidation of digital projection in the commercial exhibition circuit and the substantial reduction in the processing of 35mm prints (Labocine’s largest source of income) made it impossible for the company to continue in the long term. Since the closure of the Teleimage Restoration Center and Labocine in 2015, the film restoration field in Brazil has shrunk vertiginously, revealing that despite the initial contributions made by private companies, the sector was dependent on State resources and measures of market protection. With the exception of the Cinemateca Brasileira Restoration Laboratory, which has mainly focused on its own internal needs since 2016,13 the only option to digitally restore a film in Brazil today is the company Afinal Filmes, which started offering digital restoration services in 2017. There are projects and films to be restored, but there are no resources or public funding policies for this type of work. In fact, today, there are almost no public policies for film preservation (or for the audiovisual sector at large) in Brazil: the cultural field, in general, has been greatly affected by the government. However, in an area such as the audiovisual heritage field in Brazil, which has been historically ignored in terms of investments and marked by instability, the repercussions have been even worse. From a promising market to a struggling one in just over a decade, such is the current state of film restoration in Brazil.

There are projects and films that need to be restored, but there are no resources or public funding policies for this type of activity. In fact, at the moment there are almost no public policies for audiovisual preservation, or for the audiovisual sector as a whole, in Brazil. The cultural field in general has been severely affected by the current government. In an area that has historically been neglected in terms of investment and marked by instability, such as audiovisual heritage in Brazil, the situation is even more serious. From a promising market to decline in little more than a decade, this is the current state of film restoration in Brazil.

1. Butruce, Débora Lúcia Vieira. A restauração de filmes no Brasil e a incorporação da tecnologia digital no século XXI. Tese (Doutorado). Escola de Comunicação e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, 2020.

2. The first experience with the use of digital technology in the restoration of a film took place in 1993 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Hand & others, 1937). This project was carried out by the Walt Disney company.

3. EN: Kemeny and Lustig are perhaps best known for directing the city symphony film São Paulo, sinfonia da metrópole (1929).

4. In 1998, Líder Cinelaboratórios was purchased by investor and businessman Wilson Borges. Borges then renamed it as Labocine.

5. João Sócrates de Oliveira has worked with film restoration since the late 1970s. His career began at the Cinemateca Brasileira Restoration Laboratory. In the mid-1990s, he started to work as Technical Director at the Restoration Center of the British Film Institute in London. In 2002, he opened his own laboratory, the now defunct Prestech Laboratories. Oliveira has restored films such as Cabiria (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914), and O dragão da maldade contra o santo guerreiro (Glauber Rocha, 1969).

6. Riofilme is a Brazilian film distribution company created in November 1992 and managed by the Rio de Janeiro City Hall. Since 2009, the company has been investing in film production, exhibition, infrastructure and training in joint initiatives with the private sector.

7. Mega Studios was an important partner for the Glauber Rocha Collection project, which aimed to restore and re-release in cinemas the filmmaker's work.

8. I worked as the technical coordinator for the restoration of Bonequinha de seda with film preservationist Hernani Heffner. Therefore, the experiences recounted here are those I experienced firsthand.

9. The cost of the project was US$ 100,000 (an amount considered small for a job of this magnitude).

10. A representative of the company's development and maintenance sector even came to Brazil and witnessed the problems taking place firsthand. This dialogue contributed to the significant improvement in the Diamant software’s ability to remove the photographically incorporated scratches in Bonequinha de seda. These developments were incorporated into later versions of the software.

11. For more information on the restoration of Bonequinha de seda, see my article “Restauração audiovisual: apontamentos conceituais, históricos e sua apropriação no Brasil” (2019). Museologia & Interdisciplinaridade, 8 (15), 169-181.

12. This is true, although scratches and other damages are not exclusive to Brazilian materials.

13. Desde o início de 2020, a Cinemateca Brasileira vive uma das maiores crise de sua história. A crise vem causando muita mobilização, incluindo entrevistas e artigos sobre o assunto já publicados no Cinelimite. Vivomatografias, uma revista acadêmica argentina, também publicou recentemente um dossiê de entrevistas em espanhol sobre a crise: http://www.vivomatografias.com/index.php/vmfs/article/view/338.