“Ponta Porã – Mato Grosso – Brasil”.

This opening, after a brief prologue, takes us into a foreign land, far away from the urbanity Roberto Farias had accustomed us to in his most celebrated films, from Cidade Ameaçada (1960) to Assalto ao Trem Pagador (1962). In 1963, he set off with a film crew - and Hernâni Donato's novel in tow - to unveil a hidden country, unknown to the southeastern public at which the film was aimed. Over the course of the feature, we are plunged into a gray and ruined world of yerba mate, the remains of twisted trees and degraded epidermis, of men and women deteriorated by the heat and debt slavery in the Mato Grosso plantations dominated by the Companhia Mate Larangeira. This “cursed world of yerba mate” that "changes our way of life" is a territory cut off from everything, where the survival instinct almost always overrides any principle of morality, while the oppressive and flattened whiteness of the sky floods everything, shortens the horizon, and suffocates the gaze.

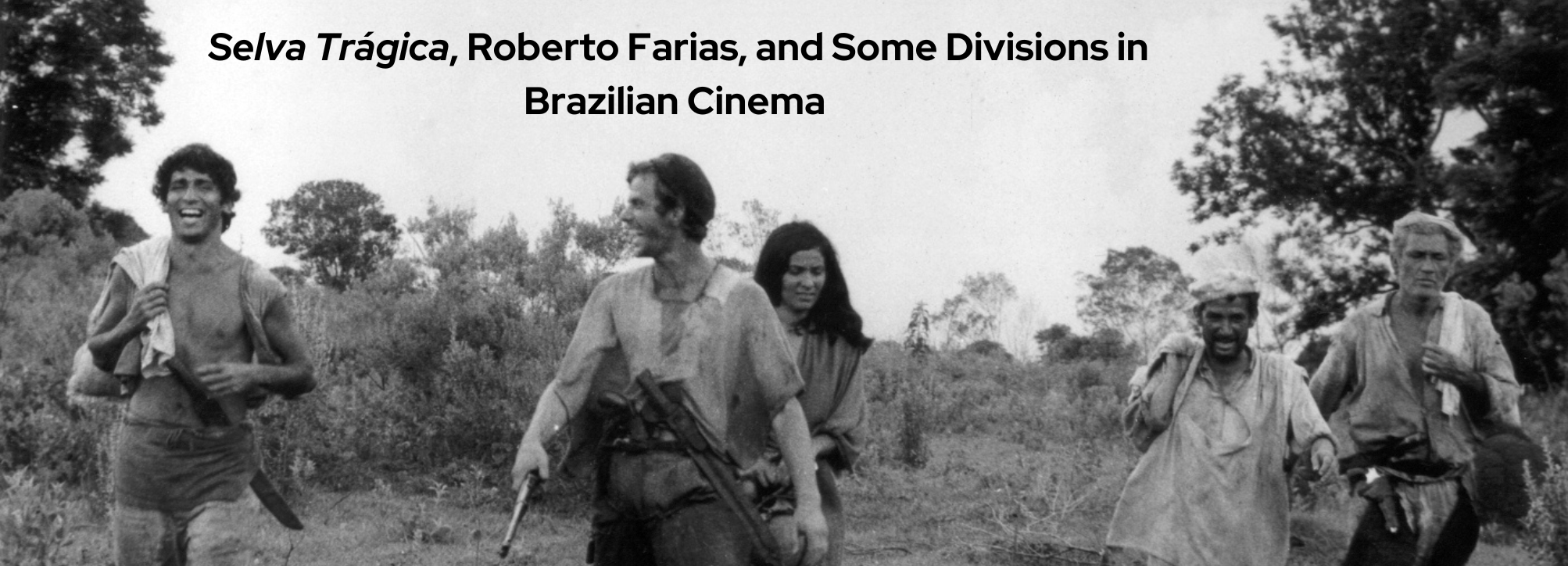

The story of the two changa-y Pablito (Reginado Farias) and Pytã (Jofre Soares), whose impetus is always to flee at any cost from the slaveholding company, in constant clash against the comitiveiros led by Casimiro (Maurício do Valle), and of Flora (Rejane Medeiros), the woman who fights with all her remaining strength to escape the fate of becoming an object in the hands of the men around her, is worked by a staging that combines Farias' dexterity with the industrial codes of genre cinema exercised since his days in Atlântida and a radical verve in line with the most hardened cinemanovistas of that time. If, as Fabián Núñez tells us, "there was never a radical rejection of [Roberto Farias] by the young cinemanovistas, despite, on the other hand, pointing out differences between them and Farias" (NUÑEZ, 2012, p. 78), it is also true that Roberto Farias is, for Cinema Novo, a "problem-figure" (ROCHA MELO, 2005), since it is neither possible to admit him unreservedly into the canon (his ties to commercial cinema are too enduring), nor to reject him entirely, as some of his works share similarities to the Cinema Novo films. One way or another, Selva Trágica (1964) is the apex of this unstable alignment: certainly Farias' most cinematically innovative film, the one in which the repertoire of forms associated with the Cinema Novo movement most clearly shows its face.

In fact, those who see Selva Trágica may be surprised (as I was at first sight) by the intensity of the long takes, by the vigorous handheld camera work, by the brutality of daily life in the grasslands, which are immediately reminiscent of the rediscovery of the interior of Brazil processed by the so-called "sertão trilogy" at exactly the same time. At first glance, it is surprising that this film does not belong to the best-known canon of the first phase of the movement, since there are so many affinities - of attitude and style - between Farias' Mato Grosso adventure and the contemporary ventures of Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, and Ruy Guerra in the Northeast.

There are plenty of reasons to defend the film's inclusion among the most radical films produced in Brazilian cinema at that time. There is no divide between José Rosa's photography in Selva Trágica and his work with Luiz Carlos Barreto in Vidas Secas (1963). In both, the work with natural light - especially with the blinding presence of an overly white sky - incorporates a suffocating illumination to the form. In the long take of a man carrying a huge load of yerba mate on his back, the cruelty of the camera is equivalent to the perversity of slave labor and there are obvious affinities with the moment in which Manoel tries to lift an enormous stone in Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964), with the difference that in Farias' film it is a worker from the region who acts as an actor, making everything even more impressive. Maurício do Valle's complex construction and nuanced interpretation as the ambiguous executioner in Selva Trágica immediately brings to mind Glauber's character Antônio das Mortes. The final chase sequence - in which the handheld camera plunges into the forest in pursuit of the fugitives while the editing operates abrupt, modern cuts - makes one think of the brutal violence of the shootout in Os Fuzis (1964).

There are plenty of reasons to defend the film's inclusion among the most radical films produced in Brazilian cinema at that time. There is no divide between José Rosa's photography in Selva Trágica and his work with Luiz Carlos Barreto in Vidas Secas (1963). In both, the work with natural light - especially with the blinding presence of an overly white sky - incorporates a suffocating illumination to the form. In the long take of a man carrying a huge load of yerba mate on his back, the cruelty of the camera is equivalent to the perversity of slave labor and there are obvious affinities with the moment in which Manoel tries to lift an enormous stone in Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964), with the difference that in Farias' film it is a worker from the region who acts as an actor, making everything even more impressive. Maurício do Valle's complex construction and nuanced interpretation as the ambiguous executioner in Selva Trágica immediately brings to mind Glauber's character Antônio das Mortes. The final chase sequence - in which the handheld camera plunges into the forest in pursuit of the fugitives while the editing operates abrupt, modern cuts - makes one think of the brutal violence of the shootout in Os Fuzis (1964).

The instigating suggestion that there would not be a total rupture, but rather a set of surprising continuities between the cinema of Atlântida and Cinema Novo helps us to think about the place of Roberto Farias - and especially of Selva Trágica - in the history of Brazilian cinema. The vastness and clarity of the classic western are here suffocated by the bursting lights of a virulent sky, by the jagged trees of a sad scrubland, by the traces of the Guarani language on the soundtrack, by the animalistic laughter that erupts without warning, by the dance music that instead of appeasing the violence, intensifies it. The linear narration is constantly interrupted by free drifting, by a dry cut or a sudden slowness, only to resume its rhythmic intensity afterwards. More than an exception in the work of a director torn in half, perhaps it is possible to find in Selva Trágica the best expression of a cinema that sketched an improbable coexistence between communicability and invention, between formal intransigence and elegance, between sympathy for rupture and appreciation for fluidity.

REFERENCES

AMÂNCIO, Tunico & VIEIRA, João Luiz. “Por que Roberto?”. In: CHALUPE DA SILVA, Hadija & NETO, Simplício (org.). Os múltiplos lugares de Roberto Farias. Rio de Janeiro: Jurubeba Produções, 2012, p. 9-19.

NÚÑEZ, Fabián. “Roberto Farias em ritmo de Cinema Novo”. In: CHALUPE DA SILVA, Hadija & NETO, Simplício (org.). Os múltiplos lugares de Roberto Farias. Rio de Janeiro: Jurubeba Produções, 2012, p. 66-79.

ROCHA, Glauber. “O cinema novo e a aventura da criação 68”. In: Revolução do Cinema Novo. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2004, p. 127-150.

ROCHA MELO, Luís Alberto. “A chanchada segundo Glauber”. Revista Contracampo, 74, 2005. Disponível em: http://www.contracampo.com.br/74/glauberchanchada.htm Acesso em 01/08/2022.

).png)