Sadness lives in the favela

Sometimes it wanders around

Then, happiness

Who was longing, smiles

And plays a little

While the sadness does not come(verses from the song "Enquanto a tristeza não vem", by Sérgio Ricardo)

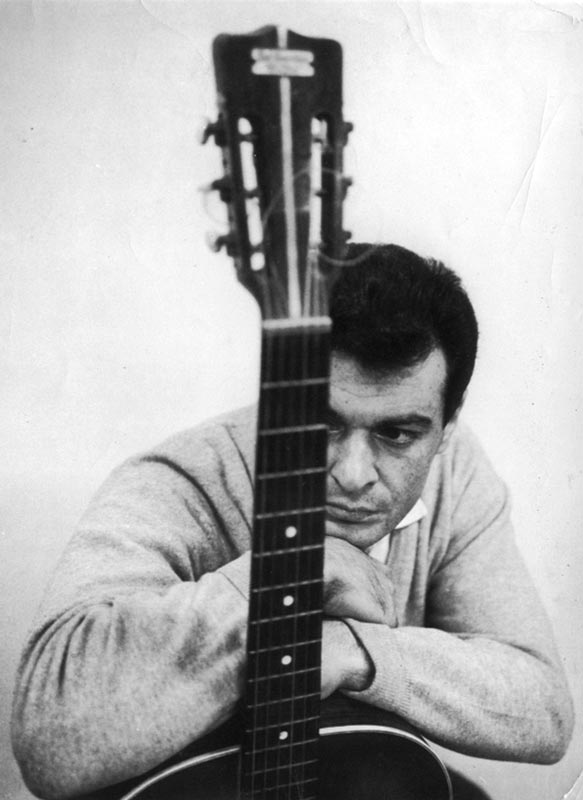

"Esse mundo é meu" is one of the most famous songs in Sérgio Ricardo's repertoire. Composed during the first half of the 1960s in partnership with filmmaker Ruy Guerra, its lyrics are a fighting call for human dignity. The historical context of the song is crossed with the utopian enthusiasm of the time, when the political revolution pervaded the Brazilian cultural field. "Esse mundo é meu" emerged as music that translated the growing spirit of rebellion against dominative social structures. Through the intensity of samba, and with a rhythm contagious to bodies and minds, Sérgio Ricardo's song sought to enunciate the epic dimension of a people who above all wished to achieve their liberation. The first few verses of the song denounce the violence of a society marked by authoritarian deformation. A nameless lyricist, who was a reflection of the historically massacred popular voice, reveals the tragic situation of their existence: " I was a slave in the kingdom and I am / a slave in the world where I am / but in chains no one can love". As a prisoner, submissive to hierarchical structures of power, the human being hasn’t got a chance of being happy. The appeals made by the lyrical self to magical entities, with their "mandingas" and their requests for help to Ogum, the orixá of war, do not result in the desired emancipation. Although it is an essential part of the country's identity, especially popular culture, Afro-Brazilian religiosity fails as an instrument to transform the world's disorders.

Faced with spiritual beliefs which do not solve dilemmas, faced with the "holy warrior of the forest / (...) [who] does not come," there is only one possible way for the lyricist to fight oppression: men and women must take history into their own hands, take the reins of the future, and become active subjects of their own liberation. As the lyrics of the song announce, it is necessary to "fight". If the statement that the world belongs to human beings is true, as stated countless times in the chorus, then it is solely up to them to transform it. In the strength of his sonorous gesture, of his call to rebellion, Sérgio Ricardo's song is structured as revolutionary pedagogy. By exposing the violence of society, from a dialogue with the musical heritage of popular origin, the lyrics of "Esse mundo é meu" (“This world is mine”) show that political resistance lies mainly in the hands and actions of the oppressed classes themselves. In the few verses of the song, hope lies in human beings, and not the supernatural, as the driving force for the transformation of existence.

A committed artist and intellectual, of a generation that took on the creative craft as an unavoidable commitment to struggle, Sérgio Ricardo provides a humanist philosophy in "Esse mundo é meu” that would set the tone of his creative path through life. Becoming a kind of manifesto, the song was covered by artists such as Nara Leão and Elis Regina. "Esse mundo é meu” contains the essence of an artistic project that Sérgio Ricardo would continue until 2020, when he died at the age of 88. In "Esse mundo é meu" we find the synthesis of a political posture, of a Marxist affiliation, that would structurally influence the works he would make over the course of decades. In his multifaceted artistic output - music, films and paintings - his critical analyses of the country, as well as his aesthetic practices, were almost always formulated with the creative and poetic considerations of the popular class as a starting point. Positioning the cultural wealth, lyricism and dilemmas of the people at the center of his creations, in what he believed to be a commitment of the militant intellectual to the oppressed, Ricardo constantly returned to his revolutionary foundational pedagogy, newly elaborating the bet on human action as a possible path to happiness. In Sérgio Ricardo's works, the people resurface continuously in the form of tragedy and liberation. If on one hand their existence is precarious, marked by misery and violence, on the other hand they possess the energy capable of operating real transformations in the world. The creative essence of Ricardo is in the oscillation between death and life, between limiting social domination and the desire to break free from these chains. His work critically exposes (and explains) oppression, but also longs for (and manifests) its overcoming.

Although Sérgio Ricardo's revolutionary pedagogy is recurrent in his songs, such as "Enquanto a tristeza não vem" and "A fábrica," it seems to me it was in filmmaking, especially that of the fictional genre, that he was able to more fully exercise the didactics behind his commitment to the popular class. In making films in which he used his own songs as lyrical and political commentaries, Ricardo found a place of creation that allowed him to broaden his readings around the dramas faced by the oppressed. The dilemmas and desires of the people, present in the verses of his songs, deepened as critical dramaturgy through his cinematographic creations. This bold narrative, built on the encounter between engaged sound work and imagery of social tragedy, are present as early as the first film he directed. Under the direct influence of Nelson Pereira dos Santos's realistic cinema, especially from Rio, 40 Graus (1954) and Rio, Zona Norte (1957), the short film Menino da Calça Branca (1962) revolves around a favela child who lives under extreme conditions of hardship. In a marginalized geographic space in Rio de Janeiro, a hill which lacks even basic sanitation, a nameless boy who lives with his mother in a small wooden shack dreams of owning a pair of beautiful white pants. In a country of authoritarian heritage like Brazil, where the value of the citizen is measured by his material possessions, such desire is not insignificant. The eager prospect of getting a new outfit, the same one used by a gallant man who strolls through beautiful areas of Rio de Janeiro, goes beyond simple vanity. In the boy's mind, this object of desire may allow him to achieve respect and a place in the world that is not available to him due to his miserable condition.

In Menino da calça branca, signature aspects of Sérgio Ricardo's cinema manifest themselves. From a mise en scène tributary of neorealism, in which the narrative develops in real locations of social exclusion, the film presents not only the perverse effects of oppression on the popular class, but also a lyrical dimension in which glimpses of happiness can be found in the child's dream for a new outfit. Present in the short film as a reflection of the people, as a means of learning about segregationist Brazil, the drama of misery and the desire for happiness would reappear sometime later in Sérgio Ricardo's filmography, more precisely between 1963 and 1964, when he began to direct a new film. In what would be his first feature film where a clear creative convergence with the Cinema Novo movement can be perceived, Sérgio Ricardo would return to the central components of his revolutionary pedagogy, this time giving it greater tragic force. With a narrative that serves as a call to struggle, of summoning the human being to break with the shackles of history, it seems no coincidence that Sérgio Ricardo's new film was titled Esse mundo é meu (This World is Mine), the same name as the song in which he had expressed the general principles of his political philosophy. In this work, made under the effect of utopian euphoria, still at a historical moment in which it seemed possible to emancipate Brazil, music and cinema come together as an act of rebellion against the deleterious state of things.

In the film Esse mundo é meu, Sérgio Ricardo's camera once again enters the geographic space of a Rio favela, this time to tell two stories revolving around the dramas of the popular class. Through parallel plots that never cross but complement each other as a diagnosis of social misery, the feature film critically reveals the daily tragedy experienced by the Brazilian people. In one of the plots, the protagonist is Toninho. A black boy who lives in a depleted shack, the main breadwinner of his mother and sick stepfather, Toninho works as a shoeshine in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Despite the hard limitations that his difficult life impose on him, Toninho is a dreamer. Similar to the child of Menino da Calça Branca, who also lives in a situation of material poverty, Toninho projects that if he could obtain a common consumer good, he would have the possibility of being happy. Gathering money day by day, little by little, he wants to buy a bicycle to win over Zuleica, a young woman who doesn't date boys who can only walk as their means of transportation. Guaranteeing social status for those who have nothing, a simple bicycle becomes the epicenter of Toninho’s desire to break free from his dire situation. While kneeling on the ground shining shoes in a subordinate position to his clients, the character gets lost in daydreams in which he imagines being on two wheels next to his beloved Zuleica. In Toninho's narrative, the desire of the people emerges as a promise, a glimpse of happiness reserved for the future. Although Esse mundo é meu can be criticized for portraying Zuleica as a stereotype of the futile woman, the film never stumbles into a political moralism that considers the particular desires of the people less important. In Sérgio Ricardo's feature film, the popular class dreams of revolution, but also of conquering the challenge to own a bicycle.

It is particularly in the second plot, with tragic dimensions, where revolutionary desire lies most. Unlike Toninho's narrative, where the happiness of being in a relationship emerges as projection, Pedro's story begins with joy. Pedro is a white man working in a small steel plant, and his narrative begins with the happy celebrations of his conjugal life next to Luzia. During a walk through Rio de Janeiro, where they go to the theater, the amusement park and the beach, the two celebrate the fact that they will live together in a shack located in the favela. The atmosphere of contentment, however, lasts for a short duration. Despite their passion, the couple faces severe financial difficulties that culminate in terrible consequences. With no expectations for the future, and faced with Pedro's failure to achieve a salary increase with his boss, Luzia decides to abort a newly-discovered pregnancy. For Luzia, there is no sense in bringing a child into the world who will go hungry. In the midst of a mise en scène that borrows stylistic elements of horror, Luzia undergoes an illegal abortion, a high-risk operation carried out inside a dirty and unhealthy shack. Pierced by twisted sewing needles during a violent storm that suddenly hits the area, the character meets an agonizing death. In Esse mundo é meu, Luzia's tragedy synthesizes the social misery faced by the Brazilian popular class. Were it not for the situation of misery, were it not for the poverty imposed by the powerful, she would probably be alive next to her son. Slaves in the world they are living in, and chained by oppression, these people have no chance of being happy. This political pedagogy, the essence of Sérgio Ricardo's art, is found in several passages of the feature film. It is present in a melancholic speech by Pedro, in which the people's joy is compared to the ephemeral taste of cotton candy, and it reappears in the sequence in which the couple rides a Ferris wheel, a moment in which the fun is ruined by the sadness chanted in the song "A fábrica". In the second plot of Esse mundo é meu, the message is evident: in an unjust society that is socially divided, the people are closer to tragedy than to happiness.

Because of this, the dual narratives are necessary. In Esse Mundo é Meu, the death of Luzia not only provokes critical reflection about the terrible effects of oppression, but it is also the last straw that impels Pedro to revolt against the patronal class. Although the call to struggle was already being hinted at throughout the course of the film, especially when the narrative is invaded by fragments of the 1963 play As aventuras de Ripió Lacraia (The Adventures of Ripió Lacraia), the effective act of insurrection only materializes after Luzia's disappearance. In Sérgio Ricardo's revolutionary pedagogy, popular tragedy and political resistance coexist, the former becoming the cause for the emergence of the latter. The sequence that closes Esse mundo é meu, a virtuous swirl of the camera capturing Toninho's joy in Zuleica's arms, seems to indicate a possible restitution of happiness, an allegory of a utopian future. But this future will only come if the workers, summoned by Pedro, really take possession of their future by coming together against the patronal class. Between 1963 and 1964, when Sérgio Ricardo placed this revolutionary gesture in his feature film, conducted by the character he plays himself, Ricardo was not alone in the Brazilian cinematographic panorama. This revolt that emerges from tragedy, an ideological consciousness acquired as a result of the pain of the world, is a recurring theme in films like Barravento (1962), by Glauber Rocha, Pedreira de São Diogo (1962), by Leon Hirszman, Ganga Zumba (1963-64), by Carlos Diegues, or Os Fuzis (1963), by Ruy Guerra. Although Sérgio Ricardo is not considered by popular historiographers to be a member of Cinema Novo, perhaps because his central trajectory is located in the musical field, Esse mundo é meu has an intense dialogue with the political and stylistic universe of this cinematographic movement. It is worth remembering that in 1964 Ricardo would compose the theme song for the film Deus e o diabo na terra do sol with Glauber Rocha, a song where we can find another return to his foundational pedagogy, to the idea that critical learning can lead to changing of social reality. As the lyrics of the song state: if the lesson that the world is wrong, that history belongs to man, is well understood, the next step will be the revolt that will make the "sertão become the sea," that will make the aridity of existence finally become a utopia.

In spite of all the desires formulated in the first films of Cinema Novo, including those made by Sérgio Ricardo, the political transformation would not materialize in Brazil. In the complete opposite of the desired utopia, on the reverse side of the dream, the country would see the implantation of a military dictatorship starting in April 1964, an occupation of power by the far right that would last at least until 1985. Represented on the screens as a revolutionary agent, through a romantic artistic imagery, the popular class would not offer resistance to the coup that imploded the fragile foundations of Brazilian democracy. In a historical context of suppressing freedom, of pulverizing the ideological projects of the left, the directors of Cinema Novo would discover the enormous distance between social reality and the utopian images that had populated their films. In part, what had served as the essence of their creative processes was now an illusion. Through self-criticism, with a certain amount of bitterness, the filmmakers would realize that their portrayal of the people, even constituting denunciations of misery, did little to match the real political condition of the oppressed class. Without escaping populism and revolutionary euphoria, they had projected images on the screens which were more attuned to their desires for engagement than to the complexities and contradictions of the world. Faced with such a fracture, Cinema Novo, in the second half of the 1960s, would change its thematic axis. In the first years of the dictatorship, taking the representations of the people from the center of the works, the directors would turn mainly to narratives about the failure of their political project, about the melancholy of militants and intellectuals of the left in authoritarian times, as is noticeable in the films O desafio (1965), by Paulo César Saraceni, Terra em transe (1967), by Glauber Rocha, and O bravo guerreiro (1968), by Gustavo Dahl. Curiously, even though directly influenced by Cinema Novo, Sérgio Ricardo would not accompany such thematic displacement, remaining firm in his artistic commitment to the popular class. Even if his cinema never returned to the previous revolutionary triumphalism, now abandoned in the face of the perversities of history, he would remain faithful to the political pedagogy in which the people, in their tragic condition, emerge on the screen as a force of rupture against oppression. Although there is a change of tone in Sérgio Ricardo's following films, a move away from the utopian romanticism that has collapsed, at the same time Ricardo's commitment to the oppressed class is kept alive, with the bet that in it lies the possible power of transformation.

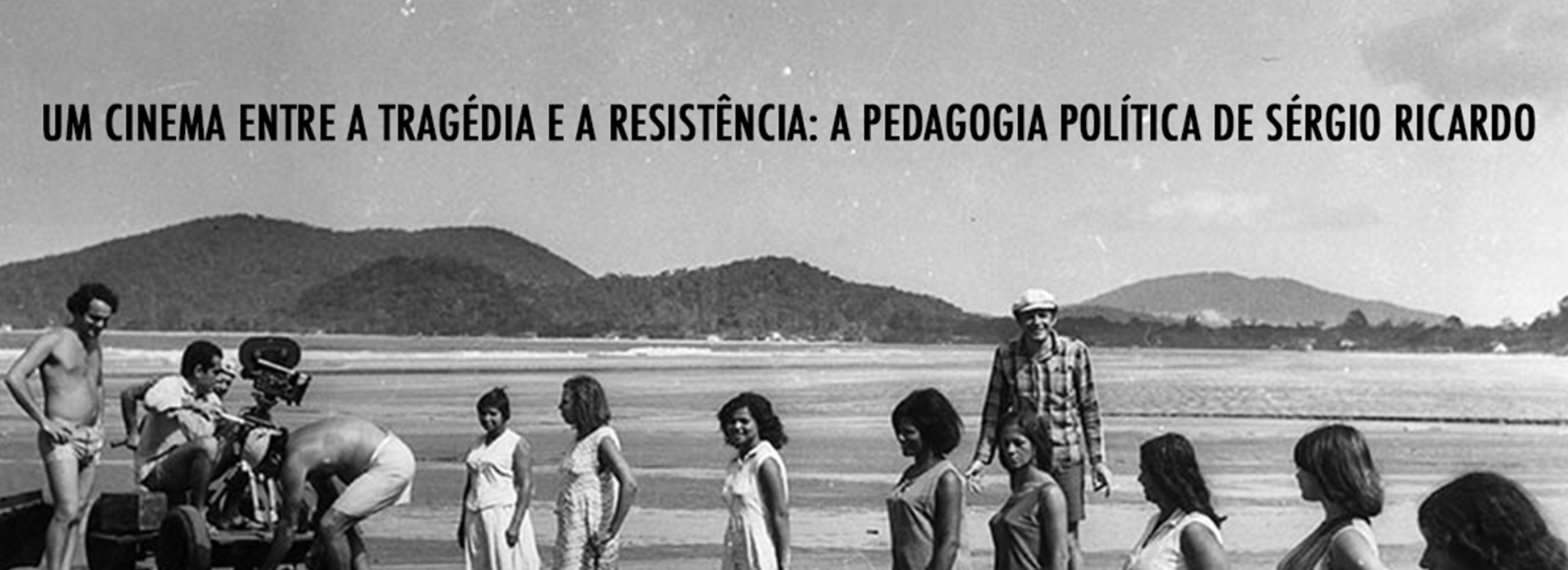

Such permanence is present in Juliana do amor perdido, a film Sérgio Ricardo made in 1970. In his second feature film, Ricardo leaves behind the geographical space of the favela, moving his camera towards the sea. In the interior of an island cut off from the world, where fishing is a means of subsistence for a beach community, the popular class emerges in the beginning of the narrative wrapped by the plastic beauty of a religious ritual. From a mystical ceremony in praise of the deities, composed of songs, drumming and gestures of worship, the local people gather to remove the fish that will serve them as food and merchandise. The ritual, with a sublime tone, derives from the aesthetic magnificence of the mise en scène, and gives prominence to the character who will become the protagonist of the film. A young woman endowed with great beauty, an element of mediation with the mystical plane, Juliana is considered by the town as the ultimate incarnation of holiness. The initial atmosphere of wonder, however, will be short-lived in Sérgio Ricardo's second feature film. Behind the beauty of the ceremony and the beauty of popular worship, there is a terrible violence that contaminates the lives of the islanders. As in Glauber Rocha's 1962 film Barravento, the religious dimension in Juliana do amor perdido serves as a power mechanism for alienating the people and maintaining social hierarchies of oppression.

What in principle should be synonymous with protection and giving, the supposed divinity existing in Juliana's body is presented in the plot as a political instrument for the containment of popular dissatisfactions. Nourishing faith and devotion around the girl, whose sanctity turns out to be false, her father exercises control over the fishing community, guaranteeing benefits through spurious agreements with an American who owns the island. Unlike Esse mundo é meu, the popular class emerges in Juliana do amor perdido not only as a victim of an unjust society, but also as an agent of domination that turns against their own peers. In a historical context marked by failing utopias, just as Ruy Guerra had done in A queda (1976), the representations of the people, now fractured between suffering and serving the powerful, become more complex. In the world of Juliana do amor perdido, in which the island's village inhabitants are left to alienation, the one who suffers most is Juliana. For being aware of her religious falsehood, for being the object of cult and male erotic voracity, and for not accepting to continue as a plaything in the hands of her own father, the character desires to break with the imprisonment imposed by existence. In Juliana's longing lies the founding political pedagogy of Sérgio Ricardo. Chained by the authoritarian structure of the world, slave to the kingdom of magic and men, the character will not be able to find happiness.

For Juliana, the chance to overcome this imprisonment will be born from an encounter with a train conductor, a man who controls the means of locomotion necessary for her to leave a universe taken by violence and oppression. The passion she begins to feel for Faísca (Spark), whose surname holds in itself the power of rupture, originates not only as sexual desire, but above all as expectation of a future in which she can shake off the enormous weight of being a false saint. In the course of her escape from her new partner's side, Juliana will finally find the chance to experience a life free from the social ties that exist in the fishing community. Like the protagonists of Esse mundo é meu, Toninho who dances next to Zuleica or Pedro who has fun with Luzia in an amusement park, Juliana sees the possible materialization of joy far from the authoritarian machinery of society. If structures of power were not causing the removal of compassion in the world, the popular class could be happy. In a moment of great lyrical intensity, when Faísca and Juliana find themselves alone on a deserted beach, the sea that used to burst as a space of domination, the sea in which the character needed to dress up as a cheating saint, now resurfaces as a metaphorical place of pleasure and rupture. Although the waters no longer contain the revolutionary allegory present in Deus e o diabo na terra do sol (1964), where they emerged as an epic symbol of an entire people in emancipation, they are re-energized in Sérgio Ricardo's film narrative, appearing as a welcoming space for a female in search of liberation. If historical time was still that of pre-1964 utopian romanticism, if the country were not hostage to a military dictatorship in 1970, perhaps Juliana do amor perdido would conclude here. Perhaps, as in the final image of Esse mundo é meu, the narrative would conclude with Juliana and Faísca in the fullness of their happiness, with a mise en scène lyrically evoking the expectation of a libertarian future.

Such an outlook, however, is not held for the couple. After a series of narrative twists and turns, Juliana will again be imprisoned by the fishing community, whose alienation turns into unmeasured violence against this "saint" who should guarantee the protection of the village and not abandon it. Treated as a traitor, imprisoned by fascist religious beliefs, Juliana will face harsh aggressions imposed on her body. During a new attempt to escape, because the burning desire for rupture remains, Juliana will meet her final destiny. In despair, pursued by the men and women of the community, she is run over by the train guided by Faísca, killed precisely by the means of transportation that should offer her the paths to possible redemption. Under the effect of the historical context of the military dictatorship, when Brazilian social contradictions were intensified, Sérgio Ricardo's cinema no longer finds the previous disposition to idealize utopian futures. In authoritarian and militarized times, the artist updates the political pedagogy present in the essence of his creative work. As a result, Juliana do Amor Perdido is a film that teaches us about the mechanisms of oppression that influence the popular class. Another example of the ideological commitment to the oppressed, the feature highlights the revolutionary energy that emanates from the people, the vitality that leads them to persistent attempts to break with the system of domination. However, even if happiness materializes, an overwhelming tragic dimension emerges in the film, a destruction reinforced by prejudices, economic interests and hierarchies of power. The life and death of the popular class, their suffering and the strength of their resistance, founding creative elements of Sergio Ricardo's art, resurface in Juliana's narrative of lost love. Updated, political pedagogy teaches that times are tragic, but that the people, as a social class, continues to contain the desiring power of rupture.

And it is precisely the life and death of the people that re-emerge, with great poetic intensity, in the third feature film directed by Sérgio Ricardo. Based on a script originally written in 1968, but taken to the screen only in 1974, A noite do espantalho (The Night of the Scarecrow) moves the filmmaker's creative process towards another geographic space of exclusion, towards the northeastern sertão. It is there that the popular class faces a life crossed by hunger and submission to the authoritarian forces of colonialism. If until then Sérgio Ricardo's filmography had been dedicated to representations around the sea and the urban favela, localizing in these territories the oscillation between tragedy and the resistance of the oppressed, now his cameras turn to one of the most impoverished regions of the country, a scenario of great material precariousness also present in the central films of Cinema Novo such as Vidas Secas (1963) and Os Fuzis (1963). Continuing the filmmaker's artistic project, expanding it towards the dilemmas found in the interior of the Northeast, A noite do espantalho brings back to the scene, as a new act of engagement, a political pedagogy mediated by the miserable existential condition of the Brazilian people.

Moving to the sertão (hinterland), a choice that is not fortuitous for a militant artist, Sérgio Ricardo would elect the city of Nova Jerusalém (New Jerusalem), located in the northeastern state of Pernambuco, as the setting for his third feature-length film. Nova Jerusalém is a city that was artificially built in 1968 with buildings that attempt to imitate the architecture of ancient Jerusalem described in biblical texts. This location is where the narrative of A noite do espantalho has become known in Brazil, it is a space of Catholic celebration in which recurring staging of The Passion of Christ takes place. Considered the largest open-air theater in the world, an icon of Christian power in Latin America, Nova Jerusalém has become a territory of religious pilgrimage where hundreds of actors and faithful gather annually to stage the suffering faced by Jesus Christ in his final moments of life. However, by placing his film in this symbolic location, of intimate coexistence between kitsch and the sacred, Sergio Ricardo was in no way mobilized by any form of respect for Catholic devotion. Keeping firm in his critical disposition against religious alienation, a position already present in Juliana do Amor Perdido, the artist borrows a locality impregnated by faith without the intention of promoting celebrations, but with the perspective of operating political ruptures in a space that is socially considered as symbolic for the devoted. By filming in Nova Jerusalem, in the same territory where emotional commotion comes from the via crucis and spiritual resurrection, the filmmaker refutes a reenactment of the last days of Christ, replacing it with another tragedy that has nothing to do with the ascetic dimensions of Catholicism. By appropriating the sanctified city, its streets and buildings, the artist removes the original Christian component, putting in its place an anguish directly related to the social reality of the country. In A noite do espantalho, in a movement of materialistic subversion, Jesus is removed from the scene. Contrary to religious expectations, Nova Jerusalém becomes the stage for another passion, that which involves the anguish and suffering of the Brazilian popular class. In Sérgio Ricardo's political theatricality, in his film of engagement, what is on display is The Passion of the Sertanejo People.

In the film A noite do espantalho, the most daring work in Sérgio Ricardo's filmography, the story about the passion that surrounds the oppressed is built through an aesthetic experience endowed with great inventiveness. Taking up what is in the essence of his creative work, a stylistic project composed from convergences with the universe of popular art, in his third feature film Ricardo seeks to establish a poetic encounter with the musicality that comes from the northeastern songbook. If before, in the film Esse mundo é meu, the samba emerged as a cultural expression related to Rio de Janeiro's dilemmas, in dialogue with the music existing in the hills and slums, now, in his new film, Sérgio Ricardo seeks creative approaches with sound roots linked to the sertaneja identity. The battle song, the cordel poetry, the wheel dance and the work songs, among other rhythmic matrices of northeastern origin, cross the narrative totality of A noite do espantalho as an operatic rhapsody that reveals the lyrical dimensions, the tragedy and the acts of survival belonging to the popular class. In the form of a passion of the people, Sérgio Ricardo's political pedagogy, the foundation of his filmmaking, is now invested in a songbook that becomes a thread of critical learning about the structures of oppression that exist in the Brazilian sertão.

From beginning to end, through sung dialogues, the film borrows traditions of popular musicality, modernizing them in order to narrate the misadventures that involve the oppressed in the interior of the Northeastern region. Like an opera of the people, a cinematographic musical about the adversities of the world, this feature film by Sérgio Ricardo puts on the screen the figure of a singer, an enigmatic scarecrow who is there to tell an episode of suffering and resistance that took place inside a small village in the backlands. Performed by Alceu Valença, who would become a nationally renowned composer and singer, the scarecrow crosses the film as a figure that holds the memory of popular misfortunes, as someone who wishes to share with the viewers his knowledge about the condition lived by the miserable class. Just as in Deus e o diabo na terra do sol, fulfilling a poetic-pedagogical function, the singer finds himself here to teach about the precariousness of existence. In announcing that his story is the fruit of truth and lies, of a fictional vein that comes directly from reality, the scarecrow invites us to become aware of the world, hoping that perhaps some form of "use and good profit" will result from it. It is from the voice of this storyteller, owner of great wisdom, that the narrative linked to the passion of the people of the sertanejo (countryside) sprouts.

In A noite do espantalho, the story presented by the singer reveals the authoritarian power relations existing in the Brazilian Northeast. In the interior of a sertanejo village, in a region severely affected by the dry climate, the popular class lives its days under the aggressive domination of the colonialist elite. A rich landowner who is the ultimate symbol of despotism, the Fragoso Colonel exercises unbridled control over the local population, forcing them to live in an oppressive state of near slavery. Subjected to the demands of power, imprisoned by the servitude imposed on them, the oppressed find themselves enveloped in suffering marked by hunger and material misery. In this universe fractured by social division, where the violence of the Jagunços imposes colonialist authority, the people seek refuge for their daily hardships in religious mysticism. However, as in Juliana do amor perdido, salvation through faith presents itself as something illusory. Despite the promises made by a messianic leader, by this figure so recurrent in the imaginary sertanejo, the miracle of redemption fails. With great frustration, the people watch the wreck of their expectations when the transforming rain does not arrive, anguishing themselves in face of the religious failure that foresaw the end of misery through the waters coming from the sky.

Faced with spiritual beliefs that do not solve the world's contradictions, acquiring political consciousness about its miserable condition, the town will seek to build an act of resistance against Colonel Fragoso. As is typical in Sérgio Ricardo's cinema, in the essence of his critical pedagogy, the tragic dimension of daily life impels the oppressed to try to break the system of domination. Once again, the foundational ideas behind the song "Esse mundo é meu" (“This world is mine”) manifests itself. To be happy, to achieve their emancipation, the popular class needs to take history into their hands, overcoming forms of alienation that impede transformative political actions. The power coming from the oppressed, however, will also fail as a mechanism of confrontation against the abuses of colonialist power. Even if a political force resides in the people that never extinguishes itself, a desire for freedom that mobilizes its existence, their attempt at resistance will be massacred in the narrative of A noite do espantalho. In the face of insurgencies coming from the miserable, who refuse to leave their lands, Colonel Fragoso orders the annihilation of the rebels. Under the watchful eye of a dragon, symbol of capitalist colonialism in Brazilian lands, a group of jagunços exterminate the sertanejos, putting an end to the rebellion that had been rising.

As in Sérgio Ricardo's other films, in A noite do espantalho, popular happiness materializes in moments when authoritarian forces are distant. Again, when the expectation of a break with the domination of oppression is drawn, a lyricism crosses the dramatic fabric as a manifestation of the joy coming from the oppressed. Especially in the sequences in which the sertanejos oppose local power, proposing the construction of an autonomous community to the colonialist system, contentment emerges in the form of a liberative power that emanates directly from the people. In A noite do espantalho, Sérgio Ricardo puts the most beautiful utopian images of his filmography on the screen. This materialization of happiness is especially evident in the moments in which the community is transformed into a collectivity, building a new village in resistance to the colonel. With a documentary-esque mise en scène, accompanied by a music of exaltation for the popular communion, the sertanejos come together and collectivize their work instruments with the intention of building the houses where they intend to live. The project of creating new homes is fulfilled from materials such as stirred clay, cut wood and tree leaves. While the mutirão (community) is being developed, something unique happens. For the only time in Sérgio Ricardo's fictional cinema, the film crew manifests itself on screen, capturing with their microphones and cameras the people's libertarian action. In a great communal act, the hands that built the houses and those that register the world share the joy of living without boundaries. The utopian power emerges in the fictional scene, but also behind the scenes, bringing together the act of artistic creation with the communal creation from the popular class. The message, put between the lines of the film, seems clear: were it not for existing power structures, this would be a possible life. In these images of plenitude, the existential bet of Ricardo resides. Unfortunately, as before in Juliana do amor perdido, the authoritarian reaction buries the glimpse of a possible future. In the form of a musical passion, Sérgio Ricardo's political pedagogy manifests itself once again, bringing forth a critical teaching about the world's suffering.

In A noite do espantalho, however, Ricardo’s political pedagogy becomes more somber due to the real life authoritarian condition found in Brazilian society. In Sérgio Ricardo's third feature film, the mechanisms of oppression do not materialize on the scene solely from the violent actions of villainous characters like Colonel Fragoso or the capitalist colonizing dragon. In the film, through a more complex approach to the authoritarian (de)formations of the country, the Northeastern colonialism emerges as a structural dimension capable of corrupting, even, the spirit of the popular class itself. Distant from the revolutionary purity that resided in Esse mundo é meu, in which the people were represented exclusively as victims of society, in the film A noite do espantalho Sérgio Ricardo makes an effort to show that the sertanejos, in the midst of miserliness, are hostages to a system of domination that recurrently turns them into instruments of violence at the service of the economic elite. As a result of the world's structural breakdowns, a shattering of the popular class emerges in the dramatic fabric.

In A noite do espantalho, the protagonist of the passion sung by the scarecrow is a man of popular origin who finds himself fractured between two distinct personalities. On the one hand, amidst the disorientation that runs through him, he appears on stage as the cowboy Zé Tulão. Performed by actor Gilson Moura, Tulão becomes the main political leader who stimulates the town to resistance. Owner of great wisdom, holder of conscience about the world, he shares his critical knowledge with the other sertanejos, impelling them to take possession of the colonel's lands as an act of rebellion against the mechanisms of oppression. On the other hand, becoming the dark face of the same man, the protagonist of A noite do espantalho also materializes as the jagunço Zé do Cão. Now played by José Pimentel, Zé do Cão carries the fate of death, representing the colonialist corruption that leads the popular class to become a murder weapon in the hands of the powerful. In his jagunça incarnation, he leads the genocide that exterminates the rebellious village. Fractured in two, crossed by existential instability, the protagonist of the film exists as both the personality of light and darkness. A metaphor of a people imprisoned by colonialist rule, oscillating between libertarian desire and servitude to power, he translates the complex effects of a society perverted by authoritarianism. Although he seeks a rupture like the cowboy Zé Tulão, protecting the transforming power of the popular class, the character cannot escape the authoritarian contamination, becoming also the jagunço Zé do Cão, assassin of his own brothers. The storm experienced by the protagonist will only end with his death, when, to the delight of Colonel Fragoso, one personality ends up annulling the existence of the other. For Maria do Grotão, a woman in love with the two identities of a single man, she finally only mourns for the one who carried the cross of shattering in life. In A noite do espantalho, the sertanejo passion endows the most complex political pedagogy of Sergio Ricardo. The imprisonment of the popular, which prevents him from happiness, is more perverse than appearances dictate. This is the teaching transmitted by the film. Suffering does not come only from hunger, material precariousness, or the tragedy associated with death. It also resides in the oppressive system that contaminates the popular class, making it exist as victim and tormentor at the same time. Even if the joy materializes temporarily in A noite do espantalho, as a lyrical glimpse of a utopian desire, the structural corruption that affects the people annihilates any possibilities of redemption.

In A noite do espantalho, Sérgio Ricardo’s updated political pedagogy also lies in the singular treatment given by him to the universe of the northeastern sertão. Without a shadow of a doubt, the feature film presents an intense dialogue with the cultural imaginary that is present in films of the first phase of Cinema Novo or in literary works written by authors such as Jorge Amado, José Lins do Rêgo and Graciliano Ramos. The passion sung by the scarecrow directly refers to the narrative heritages, especially of realistic bias, which represented the sertanejo condition through typical elements such as religious mysticism, colonialist authoritarianism, the geography of the drought or the miserable situation of the popular class. Becoming heir to committed artistic traditions, focused on denouncing the power hierarchies in the Northeast, A noite do espantalho continues a fictional imaginary that has positioned at the center of its creative processes the class conflict existing in one of the most impoverished regions of Brazil. To this tradition, however, Sérgio Ricardo adds other formal components that turn to the contemporaneity of the 1970s, endowing the sertanejo tragedy with a political and historical actuality. Enjoying great poetic freedom, the filmmaker adds aesthetic elements to the northeastern passion that freely refer to the counter-cultural experiences that were developing in the country in the wake of the persecutions and censorship of the military dictatorship.

Although Sérgio Ricardo has never been an artist of counterculture, and to defend such a bond would be a mistake, in A noite do espantalho he sought to establish points of contact with the experimentalism coming from the aesthetic vanguards existing during his time. In this sense, the mise en scène of the feature film enhances the filmmaker's political pedagogy by incorporating, into the traditional sertanejo imaginary, film forms beyond the realism that usually represented the suffering of the northeastern popular class. In the film, there are countless moments when this happens. There is the renewal of the popular songbook, the transformation of the jagunços into a gang of stylized bikers, the setting of a Tropicalist colonizing dragon, the representation of the colonist space as a modern bureaucratic apparatus or the materialization of an arena stage as a theatrical locus where Zé Tulão faces his double Zé do Cão. Updated in its aesthetic potency, the mise en scène of A noite do espantalho shows that the sertanejo passion is not something belonging to the past, but an anguish that continues to exist in the historical time of the 1970s. It is, in my opinion, a recurring effort of Sérgio Ricardo's cinematographic creation: to show, from his political pedagogy, that the oscillation between life and death, between tragedy and resistance, remains the existential condition of the oppressed until the authoritarianism of Brazilian society is overcome. Although the years pass, and countless acts of rebellion break out, suffering returns as cyclic violence that affects the life of the people.

In this sense, considering the permanence of popular movements throughout time (creating problems that are still insoluble in the year 2020), it is not surprising that Sérgio Ricardo has returned to the political pedagogy that is at the essence of his artistic creation in his final films. Despite the long hiatus that Ricardo underwent in making fictional cinema, not directing a new film until the decade of 2010, his eventual reencounter with filmmaking marked a resumption of engaged narratives where the representation of the people emerges as a transit between tragedy and resistance. In the short film Pé no chão (2014), but especially in the feature Bandeira de Retalhos (2018), works in which Sérgio Ricardo returns to film in the hills of Rio de Janeiro, pedagogy resurfaces as critical teaching about the disconcerts of contemporary Brazil. Once again, as can be seen in Bandeira de Retalhos's narrative, the lyrical and political power of the people, which materializes as an act of resistance against the expropriation of a favela, culminates in a terrible tragedy that reminds us of the imprisonment of the oppressed to the power structures existing in the country. In spite of the victory against the patrimonialist sanctity, which expels the slum dwellers from their homes in the name of real estate interests, happiness is fractured by the authoritarian violence that contaminates the existence of the popular class.

Transiting between the hills of Rio de Janeiro, the sea and the hinterland, primordial geographic spaces of the works made by Cinema Novo, Sérgio Ricardo's films manifest the coherence of an engaged artist who maintained, until the end of his life, an ideological position against the mechanisms of oppression present in Brazilian society. Keeping firmly within the ideology forged between the 1950s and 1960s, from which comes the idea that the revolutionary artist is the one who indulges in an organic pact with the popular class, Sérgio Ricardo launched himself into an aesthetic and philosophical commitment marked by readings about the dilemmas faced by the oppressed. In his cinema, which can be seen as representative of cultural Marxism, the people have always emerged as a struggling and suffering collective, as the materialization of a militant gaze that has spread specific representations of national fractures to the world. In accordance with his political thinking, in intimate contact with critical materialism, the artist imbued his work with an cinematic engagement where the popular, manifesting itself on screen, emerged above all as a social class. This is where Sérgio Ricardo's creative essence resided, it was his way of acting and being in the world. Always returning to the primordial questions which informed his thought process, to the lesson that "no one can love in chains", the artist forged a pedagogy that he believed capable of raising political awareness among audience spectators. Seeing Sérgio Ricardo's films allows us to get in touch with a cinema that never gave up its utopian desire, even though it inscribed (and evidenced) the tragedy present in daily life in Brazil. His work was constituted from the encounter between an artist of Marxist heritage and the popular class, his militancy was consolidated alongside the oppressed, and he bet on a pact that attempted to bring about real transformations in the world. For Sérgio Ricardo, from the beginning to the end of his trajectory, the belief that such transformations were possible became the foundation of his process of artistic creation. In this process, he found not only the paths of his cinema, but a humanist philosophy that mobilized his entire existence. There is no possibility for life, the artist would say, without a tireless desire for resistance.