Cinelimite: What can you tell us about the film O Roteiro do Gravador (1967)? What kind of film was it? Who was involved?

Sylvio Lanna: To answer the first question, O Roteiro do Gravador is filled with gems: it was the first film, a medium-length film, made by a restless youth who, as a 23-year-old Philosophy major, chose instead Cinema = Freedom. Meanwhile, Brazil had been under a military dictatorship since 1964, and a few months later the May 68 protests would erupt in France, where the Nouvelle Vague projected a revolutionary cinema. O Roteiro do Gravador is an existential film. It takes place from the perspective of an individual in the apocalyptic world of the Cold War (which was the situation we were living in then), and his process of knowing love and the collective. In Memoriam is in search (“...of Lost Time”) of O Roteiro do Gravador. It opens with a ?, hence why you’re very precise when you say “still searching for it within the Cinemateca do MAM archive”, after all it is two copies of the image and sound negatives of a 16mm, 30-minute film that are around somewhere… In that deposit receipt shown in the film, other works of mine are listed, they are also stored there and have temporarily disappeared. I chose to focus on Roteiro because it is the seed of my cinema - poetic, inquisitive and adventurous. Calligraphic. The main idea, an individual charging against a megalopolis with nothing but an audio recorder in which he registers his memories of an apocalyptic world, is something that I go back to, in a different way, in the fascinating sound experience that became the feature film Sagrada Família. Such is the cinema I make: one film generates the other. I belong to the generation of cinephiles that saw the birth of the concept of auteur cinema. Now, the evolution of technology has reached Dziga Vertov’s insight, and the camera is like a pen.

As for the second question, “what kind of film is it?”, I keep a website called Cinema Caligráfico de Sylvio Lanna.1 O Roteiro, first and foremost, can be classified as the first of my calligraphic films (a few of my films don’t fit into that category). Because the film was a document of a period when the dictatorship had institutionalized torture, art had to be metaphorical. The film therefore shows the slaughtering of a pig in an annoyingly violent way, bled with a peixeira2 at the Aterro do Flamengo (which was under construction then), with the city in the background. This scene accounted for radically mixed reactions from the audience of the famous Cine Paissandú 16mm Film Festival of 1967; in 74, in Copenhagen, that same scene made me lose a Danish friend. O Roteiro has the main influences of my whole life, Luís Buñuel, and the one big influence from that period, Glauber Rocha.

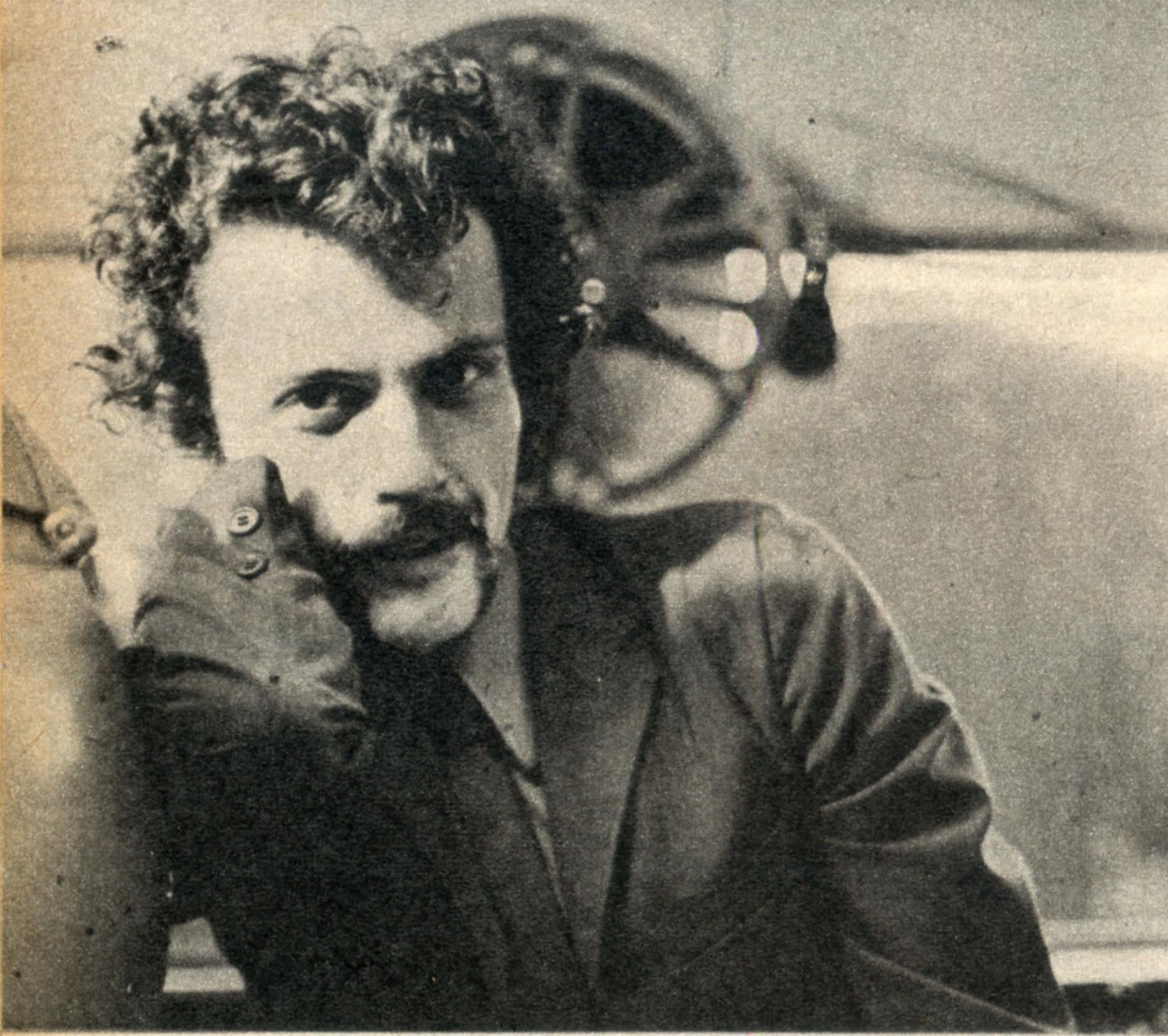

Who worked on it? Good question… In that film, Andrea Tonacci (as cinematographer and cameraman) and I sealed our immense friendship and partnership, which soon after made it possible for us to direct our first feature films, respectively Bang Bang and Sagrada Família. The main actors were the poet Pedro Garcia, who was my classmate at the National Faculty of Philosophy (Faculdade Nacional de Filosofia) and Lucia Milanez. It is imperative that, once a copy of O Roteiro is recovered, the music is preserved, with the sax solos of none other than the brilliant Victor Assis Brasil, improvised in the studio while watching the film without sound, accompanied by Flávia Calabi on the transverse flute.

CL: Did public exhibitions of O Roteiro do Gravador take place?

SL: Stories from the Cinema of Life. Today, you can store your film on things smaller than a pen drive. One generation ago, you would have to carry copies of your films in your backpack. I literally lived on the road for a good portion of my life. This was the first time I truly identified with the ideas of my generation. On planet Earth, life happens in generations. In 68, with the cash I got from German TV to produce, write, and direct “The History of Superstition Around Brazilian Football” (... and since cinema is editing, one year later I would put together, alongside Tonacci, the short film Superstição e Futebol which was awarded the main prize at the 1st Oberhausen Sports Film Festival in 1970), I hitchhiked through South America. Still in Brazil, in Rio Grande do Sul, I was arrested by the military, a suspect of being an informer of the União Nacional dos Estudantes (National Student Union), which had been designated an illegal organization. I spent fifteen days in solitary confinement, and when I was freed, I had a long talk with the colonel who commanded the Porto Alegre DOPS3 about O Roteiro do Gravador. I resumed my trip and in Rosário, Argentina, held a screening of my film at the Faculty of Medicine followed by a night-long debate. In 1979, in New York, at a party for filmmakers, we discussed the possibility of adapting O Roteiro to a New York setting.

CL: How long did it take between the discovery that O Roteiro do Gravador could not be tracked down and the decision to make In Memoriam? And what made you decide to actually begin making this film?

SL: Cinema is editing, and so is life. At least mine is. Since making films in Brazil was explicitly impossible for me, because my 1987 film Malandro, termo civilizado ou MALANDRANDO had been boycotted, my life took a turn and led me back to my hometown, and to the beginning of a long story: the project “A Bucha Vegetal Brasileira”.4 It was a practical proposition for an environmental and social educational project and these ideas were universal. If only politicians had enough will to solve the problems that afflict us…

During this project, we worked with farmers and audiovisual artists to propose changed habits of consumption and to replace synthetic sponges with biodegradable Luffas. And so, I had been far from cinema when, about 10 years ago, I got a request to sign an authorization to move the negatives of Sagrada Família, which I had stored at the Cinemateca do MAM in Rio, to the Cinemateca Brasileira in São Paulo. Together with the Cinemateca de Lisboa, they were going to finance the restoration, and make a new copy to be screened in Lisbon. I authorized it. But at first, the archivists weren’t able to find the negatives, so I had to go to Rio, where the negatives were stored after the new copy was finally made, and I witnessed the chaos the Cinemateca do MAM was then embroiled in. Now, the same situation is happening again with the Cinemateca Brasileira in São Paulo, as criminal and systematic destruction goes on throughout the country.

As to why I decided to make In Memoriam, it’s things of life (that would be a great title for a film, huh?). Life moved on, I abandoned the Luffa project, and decided to go back to making films. I met the great Cavi [Borges]. He proposed a re-release of my old films. And I told him of the importance of O Roteiro, in the same talk where I had the insight of the concept of Calligraphic Cinema. He urged me to make a 6 to 8-minute clip about the the film in the Cinemateca. That’s where the idea of In Memoriam - O Roteiro do Gravador came from.

Still about that subject... I certainly didn’t make the film for this, but the fact is, Art anticipates History. Now my film is necessary to show the world the tragedy of this new attempt at the genocide of the Brazilian soul.

CL: Who was Adriano Fonseca Filho? Why is the film dedicated to him? Do you consider your film to be politically disappeared too?

SL: That’s exactly right. O Roteiro do Gravador is young (youth is promise), politically disappeared, unarmed, assassinated, and buried without a grave in Araguaian territory.5 Adriano Fonseca Filho, like other romantics of his generation, died at age 27, after going through life like a comet. He went to college with me at the Faculdade Nacional de Filosofia, and he was my cousin. He was the first beatnik of Rio de Janeiro. Then, he became one of the first hippies. Later, he abandoned everything to join the armed resistance against the dictatorship.

CL: The film is titled "In Memoriam", as if a eulogy is being made to O Roteiro do Gravador while it is still being searched for. How does one memorialize a movie that cannot be seen? And if the film cannot be seen, what then is being memorialized?

SL: As I said before, the title In Memoriam is preceded by a ?. I still hope to find it. Just like Brazil needs to find itself again… Precisely in the archives of its past.

Anyway, I would call it an elegy to my first film (an eulogy shouldn’t be confused with an elegy, which is a poem in honor of someone’s death). The synopsis of In Memoriam reads, “A film about the death and rebirth of Cinema”. I think Cavi, in his role as the producer, passed me the ball just in time for me to score a great goal. A film about a film that doesn’t exist is, to an audience, exactly what cinema is. The eternal search for the lost treasure.

CL: The film focuses a lot on the spaces of the MAM Cinematheque and the history of the institution. Why was it important to tell the story of the Cinematheque along with the story of your film?

SL: It was important because the Cinemateque of the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Modern Art represented, to my generation of the Brazilian Cinema de Invenção, a shelter in the figure of its director, Cosme Alves Netto. It was there that, long into the night, I edited most of my films.

But also, and mainly, as seen in the opening shot of In Memoriam, due to the strong and powerful architecture of a pulsating Brazil, which began to be castrated in 1964. The MAM building, made by the architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy, is a living symbol of a time/soul in Brazil that needs to be recovered.And that may be more viable than it seems.

CL: Are you working on any new projects?

SL: Of course! Without projects, what is life? Cinema is the Art form that can’t be done alone (but hand in hand). My films almost always begin by the title; Forofina To Africa L’Afrique Na África is the name of my current project. The film stems from a Brazil/Africa/? co-production to which I am gathering new collaborators in the goal to create a non-profit organization, the Africa/Brazil/Africa Cultural Center, whose main objective is to stimulate the co-production of films in all formats between Brazil and Africa.

We begin this work with the short film Forofina Um Filme A Ser Feito. This short film intended to promote the crowdfunding campaign to gather money in. As for the plot, Forofina is a love story like millions that happen every day, each one with their peculiarities, and the peculiarity of this one is the passion between two continents, two peoples, two bloods which begets Life and more Love.

1. Sylvio Lanna’s Calligraphic Cinema

2. A large, thin knife that can go straight through an animal’s heart.

3. Departamento de Ordem Política e Social (Department of Political and Social Order), was the official repression agency of the military dictatorship, where political prisoners were taken to be tortured and interrogated. There was a DOPS building at every state capital.

4. Sponge gourd, or Luffa cylindrica.

5. The Araguaia Guerilla was an armed political movement which opposed the military dictatorship in the Araguaia river basin. During the 1970s, the military executed most of its members and concealed their remains.