“Isn't yesterday’s god the god of today?”

1. The Catulé Narrative

Before we explore the historical, dramatic, and cinematographic universe surrounding the film Vereda da Salvação (1965), we begin this essay with a narrative account and analysis of the event known in historiography as “A aparição do demônio no Catulé” (“The demon's apparition in Catulé”).1

As such, we hope to lay the groundwork for a more insightful plunge into the 1965 film directed by Anselmo Duarte, based on the play written by the São Paulo-born dramatist and writer Jorge Andrade. The theater play, in turn, took inspiration from oral testimonies organized by Maria Isaura Pereira de Queiroz (among others) in the book Estudos de Sociologia e História (Anhembi, 1957), which contains the essay “The demon's apparition in Catulé”, written by the Italian anthropologist Carlo Castaldi.

We believe this approach will allow us to extract certain elements from this episode that were assimilated by the dramatic arts and cinema, particularly in what it reverberates and, ultimately, contradicts: the underlying debates surrounding the national-popular issue.

In our attempt to both describe and interpret the facts, our references include the narratives by Castaldi as well as by Duarte himself, and the reports and analyses by Lísias Nogueira Negrão (2001), Renato Queiroz (2009), and Fabiano Lucena (2017).

Furthermore, we feel it is necessary to provide some contextual background information for the episode in question.

The historical peculiarities of the period reveal a context traversed by political-rural archaism, militarism, and radical changes in the agricultural framework, marked by the internationalization of the economy and the subsequent traumatic reordering of the geopolitics of the countryside with the forced expropriation of vast territories. As for the specific context, the episode involved small landowners who were expropriated from their lands and forced to become sharecroppers. Lacking the appropriate techniques to deal with their new location, they were forced to confront the challenges of an extremely unfavorable economic geopolitics.

Simultaneously, if we consider the ex-landowner community’s own perspective, their beliefs transitioned during the land expropriation process from a typical rustic-provincial Catholicism to the Adventist Church of the Promise, Brazil’s first Pentecostal and Sabbatarian evangelical church.

Finally, we reflect upon the distinctions and continuities between Millenarianism, Messianism, and more specifically in the episode at stake, how these terms were accommodated in a territory where American Protestantism began to exert an organic and consistent influence.

Let's move on, then, to the narrative.

In a clearing in the Forest, in a locality known as Catulé in the São João do Mata Farm, there was a small settlement of a community of 44 individuals, described at the time as “pessoas de cor” (“people of color”). Most of these individuals were illiterate, linked by ties of kinship, friendship and fellowship. The settlement was in the state of Minas Gerais, in the town of Malacacheta, in the Mucuri Valley, close to the Jequitinhonha River valley, a microregion of Teófilo Otoni.

Defined by scholars as a “political-religious movement (...) characterized by messianic-millenarian traits”, this episode seems to fall within a category of resistance and reaction phenomena, organized by traditional communities against the precarious conditions arising from forced modernization.

All of this in a country that insisted on conserving a patrimonialist and slavocrat mode of production while simultaneously embarking on a limited industrialization process. Against this backdrop emerges the “Demônio no Catulé” (“Demon of Catulé”).

It was April, 1955, when...

Worker-partners (…), overcome by a fierce mystical-religious frenzy, became the main protagonists of a social drama which has since been forgotten in academic circles: ‘The demon's apparition in Catulé’. Newly converted to the Adventist Church of Promise, our characters were involved in a tragic sequence of events: they sacrificed four of their children, killed some of their dogs and cats, and lost two of their adult men, slaughtered by soldiers who rode to the Catulé grotto in a posse to arrest the ‘fanatics’ – all this amid internal accusations of demonic possession and beatings of children and adults to cast out the devil and ‘investigate the Church of God.' (Queiroz, 2008)

It is worth mentioning how these reports described the material situation of these characters.

First, they detail how the settlers were expropriated from their lands, which was to be used for land speculation given the appreciation of the region in the wake of the newly built Rio-Bahia Highway. Furthermore, as stated by Queiroz, when transitioning to these new lands the new settlers increasingly felt the burden of unproductive individuals, mostly children, who did not serve as part of the workforce or were unable to work:

… small landowners or homesteaders, deprived of their land, found themselves forced to accept the condition of worker-tenants, living “as a favor” on the rural property of a major farmer. In this new life condition, their former material and symbolic techniques proved to be progressively inoperative to adjust to the environment. Their livelihoods, already minimal under the traditional rural system, thus became more restrictive under the rustic mode of existence. (Queiroz, 2008)

According to Lucena (2017), the Catulé community lived their lives according to the interconnection between “a logic grounded on the traditional rustic system, sanctioned above all by a rustic patriarchal Catholicism, and their shared identity through land expropriation.”

The inhabitants of Catulé abruptly shifted from being smallholders to sharecroppers, forced to share production with the owner, a fact which likely had a traumatic effect on their lives.

As Lucena explains, there was…

...in addition to a Catholic versus Protestant rivalry among sharecroppers and landowners, as well as conflicts regarding material (re)production, expressed in the hostilities which led to the displacement of the production process, in the transition from small producers to subordination to an owner and their subsequent proletarianization, the group also faced internal dissent over the distribution of labor and land as much as in religious matters.

Lacking the necessary techniques to prepare the soil they managed to occupy – according to Castaldi, “the balance between the nature of the place and the techniques available to overcome the situation gradually disappeared” – these same inhabitants converted themselves to the Adventism of Promise.

Perhaps therein lies the main characteristic through which the political-religious phenomenon of Catulé is a particularly exceptional case among the messianic-millenarian movements in Brazil: the neo-Pentecostal religious worldview served as the engine and foundation for action.

In a context ravaged by material and psychological losses resulting from the land expropriation process, the community received the visit of missionaries from the Adventist Church of Promise, when two pastors stayed in the area in 1954 to conduct liturgical actions and counsel the nascent Adventist groups at that time.

The characteristics below reveal an even more unique episode:

The Adventists of Promise preserved in their doctrines the importance of Christ's second coming as much as the belief in the Millennium, ‘integrating the Seventh-day Adventist eschatology into their teachings'. We thus conclude that Adventism of Promise is an adapted version of Seventh-day Adventism within a Pentecostal framework, a Christian branch that emerged in the United States in the early 20th century. (…): “The ‘brothers’ should treat each other with the utmost respect; any discussion whatsoever was a sin that required mutual forgiveness; likewise, it was a sin to talk about trivialities. Sexual morality was extremely strict (…) from which we conclude that, for the Adventism of Promise, the dead do not go to heaven, there is no hell nor purgatory, and the resurrection of the flesh is the only means of returning to life and only God has the attribute of immortality. The dead await unconscious in their graves until they are resurrected for the Final Judgment. Believers will be saved and shall inhabit the same, albeit renewed, land forever ‘without fatigue or weariness’, while the wicked shall be destroyed for eternity. ‘In the plan of the eternal Father, therefore, there is no middle ground’.

After their expropriation, the community converted to the new faith while simultaneously engaging in a fierce leadership dispute, mirroring the clash between Catholicism – which represented the previous traditional system – and the new difficulties brought about the new order. As Castaldi described: “alliances based on family ties were replaced by communal sect”.

The dispute was triggered by a series of factors, including a feud between Manuel and Joaquim, his son-in-law, which clearly expressed how the transition from Catholicism to Adventism of Promise had decisively changed the relations among the group.

On one side, there was Manuel, responsible for mediating the relations between peasants and landowner. On the other side, Joaquim, a 26-year-old young man, single, literate and recently arrived at the community. Joaquim, an avid and devout reader of the Bible, gradually manifested a euphoria typical of religious leaders, which ultimately destabilized Manuel's authority.

2. Catulé as a Political-Religious Phenomenon

The complexity of the episode fully manifests itself insofar as we identify the presence and subtle differences between Messianism, Millenarianism, and Messianic-Millenarianist movements.

According to Lísias Nogueira Negrão – based on the considerations of Maria Isaura Pereira de Queiroz – Messianism and Messianic movements...

...are inherently ideal-types insofar as they refer to an observable reality, but do not reproduce or restrict themselves to such reality – even if the authors categorize their concepts as empirical types. The former expresses a belief in a Savior – God himself or an emissary – and the expectation of his arrival which would put an end to the present order, seen as wicked or oppressive, and establish a new era of Virtue and Justice; the latter refers to a collective action – whether by the people as a whole or a segment of any given society – which strives to fulfill the new order desired, under the guidance of a leader with charismatic virtues.

The conception above correlates messianic movements with Eschatology, even though we may find millenarian non-messianic movements, propelled by a succession – or plurality – of war leaders, assemblies of elders, virgins, or inspiring children, etc. On the other hand, typical messianic movements may not always have the conception of a final eschaton.

The belief in Chiliasm or Millenarianism – a doctrine according to which predestined individuals would remain 1,000 years on Earth after the final judgment and experience all sorts of delights – went on to include Messianism, mirrored in the distinctive enthusiasm that shone through the figure of Manuel.

The new region imposed internal contradictions and challenges, which provoked strong feelings and increasingly fueled the imagination. Hierophanies, beatings, glossolalia, and murders resulted in a macabre combination of child and animal sacrifices as well as possession sessions, often associated with entranced states.

The logic of myth and action in Catulé suggests that, beyond the pursuit of a mythic outcome (the Chiliasm, the Kingdom of Heaven), and even prior to submitting themselves to a nihilistic self-annulment through the suicidal attitude of eliminating children and animals, the episode reveals a desperate attempt to confront an unjust political order and the impoverished material conditions in which they lived. “Through internalization, in which no longer dischargeable instincts turn inward, comes the invention of what is popularly called the human ‘soul’”, writes Nietzsche in On the Genealogy of Morality.

Entranced Earth: hierophany, glossolalia, sacrifice... everything appears to suggest the hypothesis of a psycho-collective conjuration. The Catulé event seems to transcend, in all its dimensions, the condition of a phenomenon limited to religious fanaticism or ecstasy, encompassing a series of factors through which the event stands as a type of necessary response, underpinned by a plethora of religious orders.

First and foremost a reaction to the need to cope – psychologically and materially – with the inexorable condition of being expropriated, the natural antagonism against the new landowner (whom, like Joaquim, was Catholic), the reduction of the workforce expressed in the contingent of children, the miserable living conditions, a cosmology comprised of strict practical and theoretical prescriptions towards purification, in turn associated with the need for projection and materialization.

The straight line, which would allegedly guide us from myth to irrationality, does not provide the adequate basis from which to grasp the particularity of this event.

In “Lógica do Mito e da Ação: o movimento messiânico canela de 1963” (“The Logic of Myth and Action: The Canela messianic movement of 1963”), an essay about the messianic movement that led to an upheaval among the Ramkokamckra-Canela Indians in the state of Maranhão, in 1963, anthropologist Manuela Carneiro da Cunha explains the reasons behind her thesis:

I propose to discuss that, while this cult is the counterpart to the social structure of Canela, the unfolding of the actions, as understood by the actors themselves, dialectically refer to a myth: the origin of the white man, a myth literally reenacted in reverse to present the indigenous triumph and the ultimate downfall of the white man. To this end, I place myself at the level of representations: as such we may understand the effectiveness of the messianic movement founded on logical categories of Canela thought, which ultimately furnishes cognitive satisfaction.

Amid the outbursts and pantomimes that took over Catulé in that Holy Week, may we identify some underlying thought, a cognitive difficulty? Or nothing more than irrational anger, which would later serve to justify the severe punishment at the hands of the State?

If, from the point of view of the white men who ruled these lands, there was no logic or reason, we may ask how one could expect to find reason in view of such widespread injustice and contradiction? Wouldn't the diagnosis that inferred fanaticism to Catulé provide, through an inverse movement and for the very first time, the absent arms of Law and Justice? By denying them not only a Eurocentric rationality, but any logic through which to justify their actions, they were thrown into further intense distrust and abandonment, without any support from the State or from anyone else.

On the other hand, if we acknowledge that some cognitive attitude in Catulé contradicted the dominant perspective, we may envisage other insights. In this regard, we find an underlying difference between the Ramkokamckra-Canela Indians and the events at Catulé: while the former seemingly resembles a rite or cult that had occasionally occurred in the past, what happens in Catulé seems not to obey a ritual logic, but rather a strategy of dynamic imagination, a strategy of improvisation.

Cunha concludes the essay with the following reflection:

If the undeniable driving force behind these movements is the experience of inequality, they nonetheless meet intellectual demands, as they allow us to understand that they endured a lifestyle that has barely changed over a century.

The political-religious phenomenon of Catulé: through this categorization we align ourselves with Cunha as much as Castaldi, Queiroz, and Lucena, according to which we may adopt a non-ethnocentric stance when perceiving the events, i.e., refraining from assigning fanaticism, irrationality, and illogicality to the participants without first considering the oppressive conditions in which they lived.

3. Transition from an Anthropological Narrative to a Dramatic Narrative

Carlo Castaldi's narrative, published two years after the incident, provides such a realistic portrayal of the dynamics of events that it conveys the dramatic atmosphere of grand anthropological accounts.

In an essay dedicated to the phenomenon, titled “The demon's apparition in Catulé” (1957), Castaldi describes the events to circumscribe a crescendo of seemingly contradictory attitudes, mediated by the cosmological principles of the new religion. Within this context emerged the incipient conditions through which the beating of a woman and a child transpired as natural events for the community:

We were at the end of our religious service” – narrates one of the residents of Catulé “and we were all leading prayer”. Maria dos Anjos was sleeping, kneeling on the doorstep and “did not pray”. Artuliana (Joaquim's sister) said that “it was Satan acting" and, suddenly, Joaquim jumped on Anjos and started beating her “to expel Satan”. No one reprimanded Joaquim’s second act of violence. Onofre and the others endorsed not only his actions, but his justification: “I hit her to banish Satan”. Thus, Satan was a reality so plausible for everyone involved that his existence was beyond doubt. Likewise, they believed in the real possibility of falling victim to his temptations or to be directly possessed by him. When Joaquim released the young woman, she did not run away; instead she returned to B.’s house, where she lived, and went to sleep. They had barely begun to disperse when Geraldo R. dos S. yelled that “Satan had appeared in his yard”. Everyone rushed to see and he pointed to a piece of brown sugar, which he alleged had mysteriously appeared. When we asked what led him to believe that the brown sugar had demonic connotations, he was unable to explain; he admitted the cat could have stolen it and left it on the ground. In any case, that night, after the tempestuous experiences during the earlier meeting, when Maria dos Anjos was accused of harboring the devil in her body, it seemed reasonable for Geraldo to see the brown sugar in an unusual place and blame it on the devil. Likewise, nobody else found Geraldo's account preposterous; nor did they find it absurd that Satan would leave, soon afterwards as Joaquim argued, invisible to all but him, from the brown sugar to enter Eve, Maria’s daughter. Joaquim thus began to beat Eva in an attempt to expel the demon, until Artuliana finally declared that the devil had left Eva’s body; her statement was also accepted without further discussion.

Given the radical nature of the event, plastic in its consequences, it is only natural that interest would emerge among playwrights and filmmakers, especially in light of the effervescent landscape of converging themes: violent expropriation of land, unequal relationships between boss and employees, and religious fanaticism and messianism comprising a batch of social issues that inspired middle-class movements. These movements sought not only to fight against social inequalities, but to devise a doctrine regarding the authenticity of popular culture and the paternalistic notions that orbit the national-popular.

Among these cultural movements, we find initiatives and actions that seem to exist within contradictions; nevertheless, however dissenting they may be, they share very similar material and ideological conditions. Moreover, unlike the people they chronicle, they actively participate in urban cultural circuits.

Founded in 1962, in the state of Guanabara (present-day state of Rio de Janeiro), the Popular Culture Center (CPC in the Portuguese acronym) was created by a group of left-wing intellectuals: playwright Oduvaldo Vianna Filho, AKA Vianinha; filmmaker Leon Hirszman, and sociologist Carlos Estevam Martins – in partnership with the National Student Union (UNE in the Portuguese acronym).

Their goal was to create and disseminate a “arte popular revolucionária” (“revolutionary popular art”), a venture which yielded some important films and musical albums, but ultimately proved to be as authoritarian as the national-popular Vargas project: equally regulatory of popular cultural expressions and equally authoritarian by equating such expressions to a nation-building project which, in a contradictory movement, denied the status of equal citizenship to the so-called “popular”.

The Theater of the Oppressed – founded by Augusto Boal – and the Cinema Novo movement would return to some of these issues through different approaches, while preserving the will to legislate over an extremely fragmentary population, rich in their cosmological and material perspectives, albeit dispersed throughout the miserable and violence-ridden corners of Brazil.

Both – the CPC and Cinema Novo – were concerned with formally assimilating people, individuals, and human groups that they knew only through indirect experience.

The singularity of Catulé, however, lies in how it barely conforms to the line of forces that make up the contradictions and schisms about the national-popular. Badly and poorly, the event aligns with a perspective about the democratic struggle and the public denouncement of oppression, aggravated by the 1964 Military Coup. It does not produce the conscientious harmony with which scholars attribute, even if with the best of intentions, a dimension of irrationality to popular religious expressions. This type of interpretation establishes a direct causality between myth and action – and in Catulé everything transpires not as a ritual, but following, as previously stated, an improvisation strategy.

In 1963, the poet and playwright Jorge Andrade wrote a dramatized version, baptized Vereda da Salvação, narrating these facts, with an emphasis on the Marxist vulgate grounded on negative perceptions of the connections between religion and politics – a theme in vogue at that moment in Cinema Novo as found in films such as Barravento (1962) and Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964).

For his theatrical adaptation of the Catulé episode, Andrade based his work on the studies compiled by Maria Isaura Pereira de Queiroz, published in 1957 in the book Estudos de Sociologia e História, which contains articles by Carlos Castaldi and Eunice Ribeiro. According to Queiroz, “while the playwright altered some details of the event, he remained largely faithful to the context of political and mystical ecstasy, as well as by focusing on the role of the two group leaders, merely altering some kinship relationships and the tragic outcome of the event”.

In summary, the Catulé episode found its way into Theater and Cinema through similar paths, if not in form and approach, and least thematically with the Theater of Jorge Andrade, Dias Gomes, and Gianfrancesco Guarnieri; and with Cinema Novo through the works of Linduarte Noronha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, and Glauber Rocha.

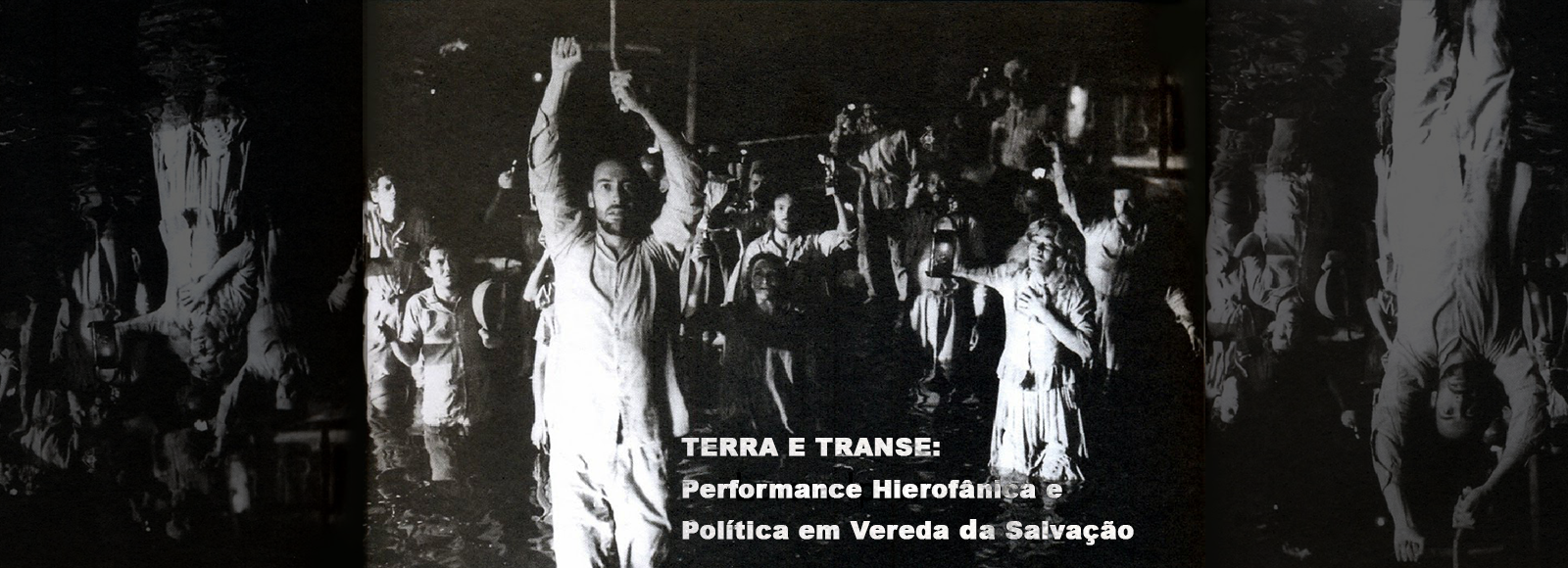

4. Film: Performance and Hierophany

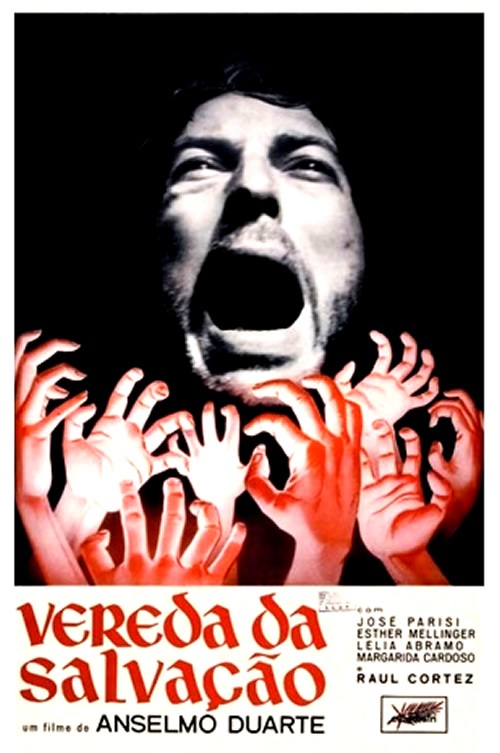

Duarte believed that Vereda da Salvação was his best work, but the film was not well received by audiences and critics alike.

One reason for such aversion is clear: both military and conservatives resented the grim vision of the land conflict. The left, in turn, disliked the oversimplified approach to social issues. Cinema Novo, especially Glauber Rocha, spurned the work for its shallow use of the cinematographic form and for issues that go beyond debates over the form of the film.

In the eyes of the young exponents of the newfangled Movement, Duarte represented São Paulo's industrial cinema. After winning the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1962, with his cinematic vision in O Pagador de Promessas, the skepticism regarding the superficial nature of his films became more prominent through the texts, essays, and declarations of the Cinemanovistas.

Glauber went further and assigned to Jorge Andrade the epithet “Shakespeare do café paulista” (“Coffee Shakespeare from São Paulo”) since, according to him, Andrade “adopts the Shakespearean methodology to theatricalize the mythology of the coffee-based economic history of the state of São Paulo.”

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Anselmo Duarte mirrors the structure of Vereda da Salvação (the theater play) in his film, directed two years later. Hence, the film’s form of expression, extremely accurate from the point of view of cinematographic desire, did not reveal the same consistency with which the visions of Cinema Novo were later opposed.

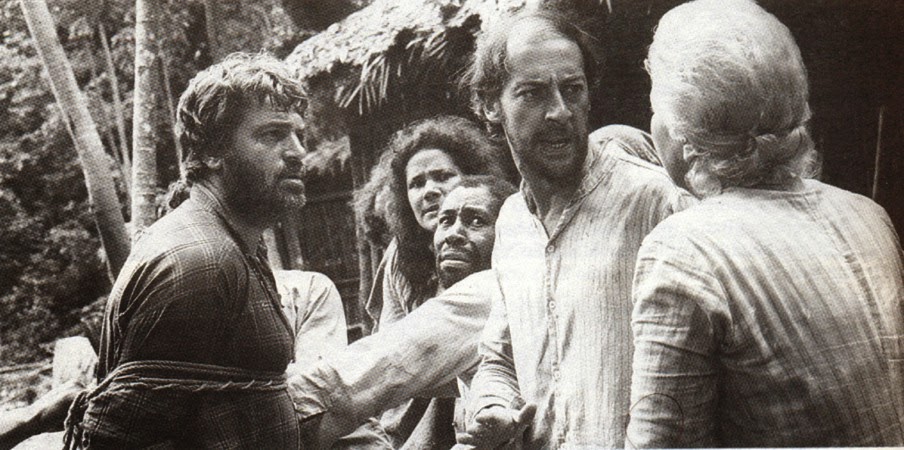

The film begins by introducing an environment: a traveling shot reveals the forest and the clearing. The camera approaches as we see the new overseers blessing the new sharecroppers. We can’t help but notice a certain naturalization of the real drama, embedded within the scenery. The country viola, like a medieval lute, emphasizes a melancholic feeling.

We gradually enter the village and its everyday world. A muller, a shelf, physical labor, scarcity. An offscreen narrative explains the process: “There was no money to fence the land and we ended up fenced in ourselves”.

Cut to a sex scene, the children eavesdrop... The joy of the children allows us a glimpse of bodily freedom, which nonetheless stands in contrast with the dialogue between the couple as they secretly plot their own wedding.

All signs of the conversion of faith are provided in the first few minutes of the film: the new social and religious condition as well as the transition to a stricter code of moral behavior. The film thus introduces an atmosphere of contradiction and imminence.

The depth of field informs a collectivity. Onofre’s speech professes the new religion, which finds a vulnerable population, whose imagination gradually begins to shape a change in behavior.

In the argument between Joaquim and Manuel concerning his wife, Maria, a brief shot shows the woman who, overcome with anger, throws a corn straw into the fire. The narrative seems to follow an escalation of mutual demands and impositions, straining relationships and creating centers of power. The continuous camera movement trails a high-angle shot ascending close to 90 degrees.

The camera returns and reveals the community: Manuel becomes a distinctive figure through Raul Cortez's body performance. The villagers slowly return to their homes as Joaquim remains solitary, in the center of the village, under the watchful eyes of the locals. Tension seizes the environment.

“You’re no longer in charge. God is in charge now”.

Under the pressure of his wife, who refuses the radical behavior professed by the Advent of the Promise, Manuel says: “They're perfecting the Church of God”.

During a harsh period of fasting, known as the Week of Penance, the children feel hungry and want to eat, but are punished and beaten whenever they risk pinching food. The sound of children, mothers cradling their babies, signal the terrifying discrepancy between real hunger and the cognitive demands brought about by the mystical fasting.

The high contingent of unproductive inhabitants is further aggravated by the new parishioners who, in the process of religious transition, must absent themselves from labor.

Disgruntled with Joaquim's frantic behavior, Maria blurts out:

“You have no wife or son, you never work the fields, and yet you want to rule!”

Joaquim’s influence on the population grows as Manuel's reputation deteriorates.

Joaquim hears strange sounds, which trigger hallucinatory outbursts. Raul Cortez’ bodily performance serves as a catalyst for the collective frenzy. He puts his hands on his head, the inhabitants surround him. Joaquim crawls as the camera frames him from above at a 90-degree angle. His body gradually twists and turns and he screams: “I feel light as a feather!”

The camera swiftly pulls away in circular movements, swayed by electronic sounds. Such was the representation found by Duarte to create the vision of a mystical delirium and its forceful projection over the community. The camera, however, seems more determined to pursue a cinematographic documentation of a theatrical performance.

Cortez incites the collective through a hierophantic performance, which possibly reaches its apotheosis with the murder of the first baby. He slams the child against a tree, which is followed by a sudden cut to a group of children crying. Joaquim's breakdown spreads throughout the community. Joaquim's mother, Dolores (Lélia Abramo), collapses on the ground begging for forgiveness.

An underlying tension pervades in Vereda da Salvação between mise-en-scène and performance: Raul Cortez and Lélia Abramo, Cortez and the collective, dance and counter-dance between camera and characters.

It is not, therefore, a specific focus on the form of the film, but a hybridity of form, which underscores traces of theatrical performance vis-à-vis a strange camera choreography: continuous shots, depth of field revealing the village environment, odd framings, precisely in the moments when conscience seems to embrace mystical laceration.

The only available copy of the film hinders our appreciation of the work of Ricardo Aronovich, the renowned Argentine cinematographer who worked with Ruy Guerra and Raoul Ruiz. Nevertheless, we may perceive an exacerbated glow in the Catulé clearing. More than underscoring the plastic dimension of the hierophantic pantomime, the luminosity seems to distort bodies, clothes, and the environment encircling the characters.

The same could be said of the sound treatment, which combines country viola with synthesizers and seems to enhance the feeling of disorientation and fatigue:

The country viola was used for the first time, whose sound resembles the lute, a medieval instrument. And I didn't limit myself to the traditional viola. I made use of electronic discharges to emphasize some of the hallucinatory moments. I anticipated a lot of things that became frequent afterwards.

Duarte seems less interested in debating the national-popular from the perspective of the political implications of messianic-millennialist movements in Brazil – as was the case a year earlier with Deus e o Diabo in Terra do Sol. Quite the contrary, Duarte seems more concerned with the singularity of the event. His most conspicuous tool is to extract the dramatic and cinematographic effects of the hierophantic performance, spearheaded above all by Raul Cortez.

As expressed by Lucena, the film consists of “representative fragments of sequences which I believe are vital for understanding this ritual performance as it incorporates an aesthetic or perception of violence within the sacred”.

This performance urges the camera crane to move up and down, creating shots that were unusual for Brazilian Cinema at the time. The actors act alongside the camera in a strange and unlikely symbiosis between Cinema and Theater.

Conscious that his work was not focused on film form, Duarte remarks on the mobility of the camera:

When I made Vereda, I had a clearer awareness of what I wanted to do. I drew upon not the mistakes of Pagador, but what I could discuss in this other film. In a way, I made Vereda against Pagador. I felt it had to be a more radical, more artistic film, away from the ordinary. If you watch Vereda you’ll see that there is not a single shot/reverse shot. Nowadays, people talk a lot about sequence shots and so on. The shots in Vereda are full sequences and the camera moves around the character just as the character moves around the camera, avoiding shot-reverse shots, which are so common in film language.”

If Duarte truly wanted to be more Cinemanovist than any other Cinema Novo director, if that desire was at the bottom of his personal project, I understand that as a minor, subjective, and anecdotal matter. Although we should recall the somewhat awkward manner through which Duarte describes the casting process:

I gathered authentic caboclos, men and women from the farms, as they were, and placed them in front of the camera, dressing the actors just like them. I had already made use of this identification between people and actors, with outstanding results, in the scenes where the crowd interacts with Zé do Burro in O Pagador de Promessas.

While we may find some of the “ingredients” of the Aesthetics of Hunger, they are not grounded on the manifesto’s underlying vision – i.e., to create a revolutionary cinematographic form, which would impel people towards a mystical-revolutionary delirium, as hallucinatory as hunger itself.

In turn, the film directed by Duarte adopts, as a structural element, a limited perception of the leftist criticism of the national-popular, unconsciously traversed it seems by paternalist and Eurocentric undertones. According to this perspective the community, lacking material conditions for overcoming misery and inequality, and reduced to a representation, allows itself to be seized by religious fanaticism and is ultimately annihilated by the superstructure.

A more consistent characterization of millenarianism and messianism could extract a political element from these phenomena, which in that moment would place Duarte’s film alongside a paternalistic approach to the people and their religion.

The opposition between Anselmo Duarte’s film and Cinema Novo was not exactly an opposition of interpretations regarding issues surrounding the national-popular.

We glimpse some points of dispute in Duarte’s definition of Cinema: “Wholeheartedly focused in my condition of a filmmaker awarded with the Palme d'Or, I believed, as I still believe today, that the recipe for success lies in providing films with a human sense, within national narrative forms”.

5. Earth and Trance

Beyond a debate about film and form, the underlying problem remains the power (or not) of a specific figuration, of a univocal notion of “the people” and “popular”. Faced with the oppression of an oligarchic structure, these populations were, in some way, ultimately forced to create means to resist and express their need to overcome their condition. The intensification of the agrarian production pattern imposed a nomadic life on populations who, for a long time, had struggled to find a place to settle.

One element, however, radically separates Duarte and Cinema Novo.

For Glauber, “the powers of the people are stronger” with their myriad cosmological views; and therefore, for that reason alone, the earth falls into a trance. That is, not solely from hunger and despair, but also due to the very power of imagination. And weapons. The Sebastianism of victory, the staged conflicts, the final triumph.

The people in Duarte, however, spoke another language:

My son may be a demon, but through no sin of our own; rather from the sin of the world. The worst demon is the evil they dealt on our lives. Joaquim believes he is Christ. May he die believing. No one can steal that joy from him.

The dialogue, originally written by Jorge Andrade and reproduced verbatim by actress Lélia Abramo in the film, may be interpreted in the wake of prevailing representations about the people, ingrained within cultural legitimation and depuration. If the national-popular distinguishes itself through authoritarian desires to legislate about the cognitive regime and praxis of the Afro-Indian culture, dispersed and fragmented throughout the territory, the dialogue at stake provides the password to reveal its deepest yearnings, its external standpoint to the object it wishes to represent.

In this regard, from an opposition between Cinema Novo and the CPC, we may appraise an apparent contradiction between Anselmo Duarte’s social films and Cinema Novo.

The role of Durvalina, Manuel’s mother (in an outstanding performance by Lélia Abramo), simultaneously embodies the voice of awareness and self-awareness. This procedure expounds the propensity of the CPC, Duarte, as well as Cinema Novo to project not only words in the mouth of the people, but to incite them with the theoretical dictates of the revolutionary construct, formulating within the film a process that they desire in concrete reality.

Lélia Abramo’s character expresses the awareness that, if sin exists (and she believes it does), it does not emerge from the community, but from the agents who pushed her towards material vulnerability and political submission; finally, the self-awareness from which she states that if religion can save her, it would nonetheless not save her son from a tragic fate, sealed by the hands of the ruling power.

The CPC visions thus embody the desire to transform the condition and conscience of the people – in other words, to make them capable of rationalizing their own condition as people exploited and abandoned by the Great Brazil and, consequently, embark on a revolutionary furor.

Rationality, a sign of authority that restores to the Latin American intellectual the mission of building a nation, is in turn imposed upon the cognitive forms of a national-popular sphere that he knows through idealization, through hearsay. Yet it is in the equivocal nature of the fragment, rather than in the totality of the national myth, that this real and concrete national-popular seems to elude both the representations of the CPC and those of Cinema Novo.

The clear divergences between the dictates that guided the practices at the Centro Popular de Cultura (CPC) and Cinema Novo existed beyond the debates about the libertarian and authoritarian dimensions of the national-popular and its criticism. In this case, we must pay heed to the debate about form in the representations of “popular” expressions within the Atlântida and Vera Cruz productions: “the language that communicates with the people”, as stated in the CPC manifesto – which stands in contrast with the notions of language and form immanent to the Cinema Novo aspirations.

In fact, despite prior experiences, as found in the films of Nelson Pereira dos Santos and Linduarte Noronha, Cinema Novo embarked on a formal research which strived to be both aesthetic and revolutionary, while simultaneously communicating the announcement of a renewal and announcing the expansion of direct communication with what they believed or intuited to be the people. “

The Cinema Novo folks failed to understand that to speak to the people, one must use a language that the people understand” – writes Carlos Estevam Martins in A Questão da Cultura Popular, an argument that would be mirrored by other critics such as Jean-Claude Bernardet.

Both the CPC and Cinema Novo nurtured the belief, each in their own way, that a univocal form of the national-popular is embodied in the concrete experience of the people: the box-office-people of the cities, the folk-people in secluded pockets of poverty, and other reductions of the people to an ideological – or at least idealized – role.

In effect, the authoritarianism of the National-Popular expressed itself in both poles, perhaps as a consequence of the very material condition of those involved. The fact remains that between Anselmo Duarte’s visions of popular cinema – which ranges from the “chanchada” in Absolutamente Certo (1957) to the construction of O Pagador de Promessas (1962) – and the formal-revolutionary exploration introduced by Glauber Rocha in Deus e o Diabo and Terra em Transe (1964), one finds a crucial distinction, if not a formulation, of the constituent element of the leftist Latin American intellectual: the need to situate their performance within the realm of the indispensable, whether to affirm or deny the power, at this point equivocal, of the national-popular. Glauber was elevated to the position of auteur and herald, interpreter of the world, subversive intervener, while Duarte wished to embody the typical hyper-active filmmaker of 1940s industrial Hollywood.

It is precisely the evasive, weakly rational, and entirely non-experimental character of Duarte’s films that leads Glauber to attribute to them a pernicious influence.

O Pagador de Promessas foments the most dangerous trend in Brazilian Cinema: (…) award-winning and profitable films that disseminate nationalist ideas with evasive solutions; they impose a spirit of production, envelop the masses with such themes, dominate irresolute elites, arrest useful innocents, and are effortlessly co-opted by reactionary forces, who find a perfect outlet in this type of pseudo-revolutionary nationalism.

Duarte explains his approach:

“One finds in Vereda a terrifying portrait of Brazil” – declared Anselmo Duarte. If his film was accused of “trying to resemble Cinema Novo”, this so happens because, at some point, Duarte's success as well as the form and approach of his films, was not recognized by Glauber as a filmic expression of Cinema Novo.

Even the middle class, to whom Vereda was addressed, echoed a limited conception of the national-popular; whether the very few, who admitted some qualities in the film, as well most of its critics. Duarte, who considered that “Glauber’s generation practiced the worst Cinema in the History of Brazil”, defended himself:

Another issue, which I will address shortly, is the negative reception, both of the audience and critics at the time for the work Vereda da Salvação, whether in the film screening or the theatrical staging, which in some way reveals its discomforting effect on viewers, built upon the fictionalized ritual dimension. The debut, both of the play and film, occurred shortly after the 1964 Military Coup, and the malaise was felt both by the Right, who felt bothered by the exposé of the peasant situation in the countryside, and the Left, who accused the work of being mystifying and presenting mystical alienation as the only solution for class struggle.

There is, however, a second crucial distinction. Vereda da Salvação is ultimately closer to a pious gaze, the Sebastianism of waiting and hoping. Glauber Rocha had previously written about O Pagador de Promessas in Revisão Crítica do Cinema Brasileiro: “Constantly exciting: it does not provoke the slightest reflection. (…) the elation is purely sensual”. Conversely, Glauber wished to capture the expressive power of the people, combining it with the emergence of a thought, a cognitive organization capable of producing some kind of disruptive action. In Terra em Transe, the mystical-religious power of messianic and millenarian movements creates a philosophical arena that sets the stage for other mythical expressions. Glauber’s vision of Messianism is ultimately guided by the notion of overcoming, whether through the deterioration of relationships, the concrete staging of an overcoming; or the overcoming of not only the oppressive enemy, but the social order itself, which subjects individuals to a life of misery and material inequality. Glauber perceives these movements, usually regarded as pious or critical fanaticism, in their potentially disruptive dimension.

In Vereda da Salvação, both play and film, the community seems as if enthralled by the Eurocentric logic of fanaticism, which only admits reason if grounded on a scientific order. For Glauber, the encounter between Myth and Action breeds a disruptive power. The communities taken over by a political-religious frenzy utilize this transit, between delirium and action, as a tool, in the words of Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, “to outline institutions” – institutions capable of sheltering and enabling their ways of life.

Jean Rouch’s film, Les Maîtres Fous (1955), springs to mind, which documents the Hauka ritual whose participants enact, under the effect of a trance and following a dramatic script, a certain twist of the Social Order. Much like the inhabitants of Catulé, the participants in the Hauka ritual change their names and become agents of oppression: American military personnel, doctors, engineers… As such, under the effect of a trance, mystical-religious performances carry the political power to incite a critical relationship with power.

1. We express our gratitude to Luísa Valentini and Ewerton Belico for their suggestions and careful reading of the text.

Referências

ARAÚJO, Fabiano Lucena de. “O sagrado e o milênio em Catulé: a performance fílmica e a estética da violência em um movimento político-religioso, a partir da obra Vereda da Salvação (1965)”. In: REIA- Revista de Estudos e Investigações Antropológicas, ano 4, volume 4(2):199-217, 2017.

CASTALDI, Carlo. “A aparição do demônio no Catulé”. (1957) São Paulo, Tempo Social, revista de sociologia da USP, v. 20, n. 1, 2008.

CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da. Lógica do Mito e da Ação: o movimento messiânico canela de 1963. In: CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da. Cultura com aspas e outros ensaios. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2009, pp. 15-49.

LINHARES, Maria Yedda; SILVA, e Francisco Carlos Teixeira da. Terra Prometida. Uma história da questão agrária no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Campus, 1998.

NEGRÃO, Lísias Nogueira. Revisitando o messianismo no Brasil e profetizando seu futuro. Rev. bras. Ci. Soc. [online]. 2001, vol.16, n.46, pp.119-129.

QUEIROZ, R.S. 2015. O Demônio e o Messias: notas sobre o surto sociorreligioso de Catulé. in: PEREIRA, J.B.B. & QUEIROZ, R.S. Messianismo e Milenarismo no Brasil. São Paulo: EDUSP.