When dealing with matters of film history, specifically its archiving and curation, one quickly learns that the establishment of “firsts” is a fool’s errand. To begin with, it is not our collective ignorance about this or that film that necessarily determines its extant status. But the agreed-upon legend states that Um Clássico, Dois em Casa, Nenhum Jogo Fora (1968) is the first film released in Brazil with characters explicitly displaying same-sex desire.

But claiming to be the first is not what makes Djalma Limongi Batista’s debut a special object. Its bold and experimental manner is what stands out most and continues to resonate well with contemporary audiences. Its revolutionary style, contributing to one of the most creative eras in Brazilian film history, has been left aside for too long, but its status is slowly but surely witnessing restoration.

Fifty-odd years after its initial production, Um Classico is perhaps not the type of work that the average budding cinephile would associate with the established canon of queer cinema landmarks. It is not romantic, it is not sweet, it is not hopeful or particularly uplifting. It does not deal directly with the representation of an externally homophobic society — in fact, the only moment of homophobia is acted out by one of the film’s protagonists.

Batista has claimed decades later that the film owes too much to existentialism, in particular the works of Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Franz Kafka and Virginia Woolf. It is a very 1960s film indeed, with its mélange of references and anxieties, coupled with a certain feeling that although the world is in turmoil (and the soundtrack certainly helps in that regard), there is nothing we can do to change it.

It is a film from a time in which there was no need or desire to include a moral statement at the end. The characters were not supposed to be mirrors for the spectators, and such is how they operate in Um Classico. They behave strangely, they do things that one would not expect them to do. How would one go about explaining the end of the film today, in which the characters don't fulfill any teleology?

Our protagonist and his desire for hookups is something that is not (yet) socially permissible and the urban world seems like a completely alien concept to him.

To understand the impact of the film, we must therefore explore what is now - retroactively - considered to be the early stages of Brazilian queer cinema, with its elusive representations of LGBT identities, desires, acts, and characterizations. We will also do a brief overview of Limongi Batista’s life and work leading up to the production of the film.

Queer cinema in Brazil beforeUm Clássico, Dois em Casa, Nenhum Jogo Fora

The first compendium on LGBT representation in Brazilian cinema was produced by Antonio Moreno, in his master’s thesis, completed in 1995 at the State University of Campinas. Titled “A personagem homossexual no cinema brasileiro” (“The homosexual character in Brazilian cinema”),1 the thesis was very much indebted to the line of identity theory established by Vito Russo for American cinema and disseminated throughout the world in many LGBT film histories that were being studied during the 1980s and 1990s.

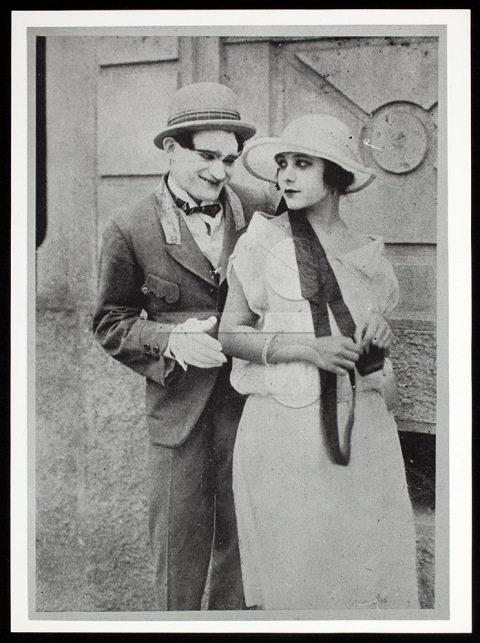

Transformed into a book published in 2001 and finding a later iteration as a film festival in 2014, the filmography of Brazilian queer cinema begins with Augusto Anibal Quer Casar (Barros, 1923), a lost silent short in which friends play a trick on the protagonist, who discovers at the altar that his bride is actually a man, played by Darwin, a famous theater “Transformist”, as it was billed at the time.2

To Moreno, after a handful of films that either showed queer characters as a laughingstock or only as subtext in films, it was only in 1960 that a film clearly addressed same-sex desire, with the release of Bahia de Todos os Santos (Neto, 1961). Luiz Francisco Buarque Lacerda Júnior, also known as director Chico Lacerda, agrees with this assessment in his study on the vast history of male homoeroticism in Brazilian Cinema, “Cinema gay brasileiro: políticas de representação e além”,3 but brings attention to the fact that while homosexuality is never expressed, it is clearly understood by connotation.

It is the same connotation that I present in my analysis of Poeira de Estrelas, a 1948 lesbian film, in my MSc thesis “Em Busca de um cinema queer no Brasil”, presented at Universidade Federal de São Carlos.4 The trouble with connotation is that even if it is more obvious than subtext, it still may pass unnoticed either by absent-minded spectators or by (rare) foreign viewers, relying on poor subtitles that do not fully capture the nuances presented by the script. A handful of other films released before 1960 prove this point: although they are analyzed on those two landmark studies and my following contribution, there is no evidence that they were understood at the time as representations of same-sex desire or acts.

Lacerda goes on to point out two mid-1960s films that display homosexuality more explicitly than ever before, but never focusing on the desire felt by the characters, and instead on the fear and persecution suffered by the main character, judged and persecuted due to a homophobic society. While a British film like Victim (Dearden, 1961) showed the ordeals suffered by a number of closeted people in a successful attempt to politically impact and overturn anti-LGBT laws in the UK, the Brazilian films O Beijo (Tambellini, 1964) and O Menino e o Vento (Christensen, 1967) never acknowledge the desires of their characters in a country that has never officially forbidden same-sex relationships, but always found ways to control it.

In both of the aforementioned films, our protagonists are exposed as deviant, gay, and referred to by several Brazilian terms equivalent to “fag”. Not only this but they also become suspected of crimes related to their supposed queerness. While the Brazilian law never forbade same-sex acts, it had several measures that could be used to jail people who looked or acted gay.5

We can therefore safely assume that Um Clássico, Dois em Casa, Nenhum Jogo Fora was truly the first film to openly show LGBT characters that desire each other and for that, it was a groundbreaking work. These men never kiss or promise their love to each other, but their desire is pledged. They still feel persecuted, like the other films, but for the first time we are somehow on their side and no longer pretending that they are “innocents”.

In O Beijo, based on a Nelson Rodrigues play, our protagonist is subject to an ordeal after a dying man asks for a kiss on the lips as his last wish and becomes an innocent victim of homophobia, only to find out at the end that his father-in-law, the instigator of many of his problems, secretly desires him, while portrayed as an old and disgusting queer.6 In O Menino e o Vento, an old queer colleague comes to shed light on some of the shadier aspects of our protagonist’s life, who is on trial for the disappearance of a local boy, with whom he shared a very affectionate and loving relationship.

In both films, innocent straight characters in need of help and full of love are put through tribulations because a sickened society sees wrongdoing in their pure acts. If in the end of O Menino e o Vento, a gust of wind operates as deus ex machina and seems to show that the love shared between the protagonist and their lover is stronger than anything, it could also be read as a sign of “innocence” of the man guilty in the eyes of a scared society.

These were the ways in which homosexuality was depicted until the mid-1960s, as a frightful mark that any innocent man could be tagged with, wrongly accused of such an act.7 But we must assume the existence of a queer audience in Brazil for whom these works would provide some sort of recognition. That perspective obviously suited theorists and researchers focused on the aspect of identity, but if they were to follow a strict chronological path, they would be left puzzled by Um Clássico, which as we shall discuss, still uses some aspects of this game as its protagonist somehow falls into a trap by another queer man, but turns its head around as he voluntarily follows his desire and eagerly accepts his fate.

Djalma Limongi Batista managed to be an outcast both in the bigger scheme of Brazilian film history, but also during the first wave of LGBT revisionism, that could not properly identify if the characters in Um Clássico were good or bad, unable to trace how they connected to a broader gay community, or answer if they showed a positive or negative aspect of homosexuality. This assumes, obviously, that they could watch the film in the first place. Highly celebrated in the (small) festival circuit at the time, it was soon to be censored and shelved, but not forgotten and luckily not lost. Now, restored and again making the festival rounds, it resumes once again its place at the forefront of queer film history. But before we delve into the film, it is important to turn back to understand Djalma Limongi Batista, the man behind this film, and the time/circumstance of its release.

The Formative Years of Djalma Limongi Batista

Brazil’s film history, like many other national cinemas, is known to be full of “cycles”, or waves, usually very short-lived and with different degrees of success in the continued hope that one day the industry would surge. One-time wonder Mario Peixoto, creator of the landmark masterpiece Limite (1931), could be described as the patron saint of Brazilian artists caught in the rolling tides of lack of funding and industry, who were not able to forge a large and multifaceted body of work. It would be possible to create long lists of amazing films that were made by directors who never went back to the set after having impressive debuts.

Djalma Limongi Batista is one of the main figures of Brazilian cinema who, despite not being able to create a long and stable body of work, managed to produce a lasting impact on film history with his handful of films.

Batista only directed three feature films, released between 1981 and 1997. Together with his first three short films, shot in 1968 and 1969, Batista created a unique visual and thematic style. Rarely seen until today, Um Clássico is still a hugely unique experience, but still connected somehow with other films made during the period. It is such a shame that he was not able to continue his career, partly due to funding issues and controversy over his projects, but also the lack of a more robust film system in Brazil, which leaves some out-of-place auteurs without resources to film their worlds.

Born on October 9th, 1947, Djalma Limongi Batista lived in a large house with his parents and seven siblings. His hometown of Manaus, at the heart of Amazon forest and the most important city on northern Brazil, used to be a very rich city at the boom of rubber exploration in the early 20th century, but by the 50s it had regressed to the status of a fairly sleepy and rainy town surrounded by huge buildings that reminded its inhabitants of an opulent past.

It was in this atmosphere that Djalma and his brother Gualter used to go to the movies at every opportunity, forging a shared passion. When it was time to go to college, Batista’s father, an important doctor and scientist, was able to take him during work trips to get to know the main cities and universities of Brazil. He had chosen to enroll in the new University of Brasilia, one of the leading projects from the recently built capital of the country.

There, he met Paulo Emilio Salles Gomes and Jean-Claude Bernardet, perhaps the two most influential Brazilian film scholars of the era, responsible for a revolution in Brazilian cinema studies: their ideas of values would discreetly but surely shape Batista’s films, and their connections to Brazilian culture, society, and history.

Batista moved to Brasilia in 1964, the same year a military junta deposed João Goulart, the sitting left-wing elected President, and started its process of clawing to power. At the end of 1965, during a political clash between the federal government and the country’s professors, the UnB was shut down. Suddenly feeling lost, Limongi Batista told a biographer that he had been given an opportunity by a colleague of his father to go to the University of California, Berkeley (where he could have conceivably been a classmate of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg). Instead, he decided to follow the path of his mentors in Brasilia and go to São Paulo, where Salles Gomes, Jean-Claude and Lucila Bernardet created a film course at Universidade de São Paulo (USP).8

With USP’s location in a metropolis full of social inequality, it was natural that the professors at the Film department would prefer to produce documentaries, especially at a time in which the camera and sound equipment had become flexible enough to go on the streets and film ‘reality’, resulting in a production boom in the documentary mode in Brazil. So, it was quite a shock when Djalma jumped the gun and created Um Clássico on his own and with a little help from his friends. Its 28 minutes of personal conflicts amidst a crazy and angst society somehow had the “documentary style” that his professors hoped for, but no sociological thesis behind it.

The film opens up with close shots of Antonio, played by the handsome and fresh Eduardo Nogueira, waking up on a bed to the sounds of a football match on the radio. As the camera shows the rest of the room, we see another man grumpily adjusting his tie as Eduardo slowly awakes to the day. One could assume that this is a sexual partner and the film certainly invites this idea for the confused viewer, but we find out that it is his brother.

Next, we see the family kitchen, where the father, mother, and brother discuss various problems of the middle class while being served by an older maid, a constant presence in Brazilian families. The father complains about not getting a promotion at his job, and all find a common interest in belittling the lazy brother. Scenes like this set around a kitchen table over breakfast could be seen all over the Brazilian cinema in late 1960s, most notably Copacabana Me Engana (Fontoura, 1968). Just as in the British kitchen sink realism films, these scenes oppose the running wheels of the Brazilian middle-class and outsider characters who are desperate about their socio-economic situation and not sure how to get away from it.

Unlike Fontoura’s feature which created a world where the rebellious younger and older brothers could find in sex some common ground, Limongi Batista promotes a total rupture. After the “men of the family” leave for work, Antônio finally gets out of bed to find the women of the house doing their daily chores, and goes outside, perhaps to never return.

Probably the most interesting scenes from a contemporary perspective would be those where the protagonist walks around São Paulo’s downtown, crossing with many people in their day-to-day lives. In the age of portable phones and images everywhere, it is curious to see how those kinds of shots were common in Brazilian cinema from the 1960s and 1970s and slowly disappeared as people grew more self-aware of their image and media impact. To a current spectator, it offers an amazing glimpse of urban São Paulo in the 1960s and its citizens.

Those shots establish the world of Antonio, lost in the crowd and eager to find someplace to fit in. He goes to a shop, where a friend works, and they have an argument in the middle of the street, where they appear to break up. We can assume that probably is an ex-boyfriend, but at the time we are left to wonder what has happened. We enter into Antonio’s world step by step, where there is too much confusion, noise, and obstacles around him. He walks around, watches a colorful wrestling fight - extremely popular at the time - browses magazines, until in a POV, the camera focuses and flirts with another boy. We may risk labeling this as the first moment that homosexual desire was put at the forefront of Brazilian cinema. No connotation, no hidden text: Antonio looks at Isaias (played by Carlos Alberto) and wants him.

The final act takes place in Isaias's apartment. As he declares that “I’m not from here, I’m from the north, very far from here”, on some level he may be seen as a representation of the director himself, a country boy lost in the big city, not sure how to find his way. Antonio also reassures him that “I'm from the Northeast, I came when I was 11 years old”. São Paulo, a no-man’s land that is also a place in which queer people can seek out those like themselves. A place for strangers to call home.

The two boys never kiss, have sex or completely undress on-screen, so perhaps a modern queer audience would leave the theater a bit disappointed. But they caress each other, show desire for one another. Isaias asks to be killed because he knows things are never going to be the same after this encounter and as they can not be together, he might as well die. Antonio seems to be taken aback but eventually agrees. The problem is that now he has also entered a world from which there is no return.

According to the director in his biography, "at the time, I started to have some of my first concerns with my sexual orientation, and as I was always too impetuous, I decided to write it down” (39). He also said that:

"The funny thing is that it never crossed my mind that to make "Um Clássico..." was a courageous act. Today I see it like that, but at the time it was just fun and games. Or, perhaps, a revolutionary need. The 20th century's sexual revolution was happening!” (41).

It strikes one that such a profound work, overtly influenced by existentialism, was the first film at all from someone with no experience on film sets whatsoever. Perhaps, it had to be the first film in order to show such raw emotions, the equivalent of a 1960s version of the equally anguished and full-of-melancholic-queerness Limite.

A very important dialogue happens when the two are in Isaias’s apartment. He tells Antonio that sometimes “some fags play ‘Free Again’, a very faggoty music and ….”, adding that “they are so fag”, and that seems to be the key to understanding the fate of our players. The song by Barbara Streisand goes on to blare “Free again, independent me, free again”…“back to being on my own”. Antonio and Isaias are both free, they can cruise and express their desire on the streets of São Paulo, but society and family still control them, and they can never truly choose their own destiny. They act free for now but know their freedom will not last.

As the boys look out the window, they only see people whom they can not possibly relate to, either the average and straight man, a product of the system, or the “fags” that proudly display their queer bodies and voices. They don’t identify with anything, caught between pride and shame of what is already perceived as an identity, something you can not deny. Early on in the film, Antonio apparently breaks up with his first boyfriend because he saw him with a woman. It is a sign that the former option of being in the closet and living a “straight” family life is not on the table anymore, but we are still in the middle ground, queer public life is not yet acceptable if it does not break away completely with tradition in society.

Antonio and Isiais are lost on their own, and there is no way out. That description unfortunately would not be inapt when applied to Limongi Batista’s life/career after this film. The film premiered at the Short Film Festival promoted by Jornal do Brasil, one of the leading newspapers at the time. It was a sensation at the mythical Cine Paissandu, and the film won best film, director, editing, screenplay and actor for Nogueira. The film caught the attention not only of the main Brazilian filmmakers who were at the festival, but also from the press, with a more negative note coming from the professors at the University who had no idea Batista was already making films. Batista’s father even flew to São Paulo with concerns about the themes presented by the film. If nowadays some people do their coming out in Youtube or Tiktok videos, Djalma Limongi Batista was a pioneer in staging his coming out with an awarded short film.

Um Clássico, Dois em Casa, Nenhum Jogo Fora was the first film produced by the Film Department at the University of São Paulo (USP). Limongi Batista followed that with two other experimental short films made in 1969, O Mito da Competição do Sul and Hang-five, always with Eduardo Nogueira, a “handsome swimmer and surfer, dazzling, that instantly became my fetish-actor”.9 Following this, he helmed three short films Puxando Massa (1972), Porta do Céu (1973) and Rasga Coração - O Teatro Brasileiro de Anchieta ao Oficina (1973). All of these films are documentaries, more aligned to the intellectual interests of university policies, but still with an eye to the human behind the mass, the individual inside the collective, and nods to the baroque style of Um Clássico.

In the 1980s, Batista finally directed two feature films, amid working in advertising and photographic laboratories: Asa Branca, Um Sonho Brasileiro, in 1981, and Brasa Adormecida, five years later. Both of them can be seen as part of the 1980s Brazilian cinema towards a more visual and spectacular cinema, something particularly true to São Paulo’s filmmakers. They are, perhaps, the perfect definition of queer: while there is no overt homosexual plotline, they are always present on the subtext and the male body is treated as an object of desire and affection.

In Asa Branca, Batista commits the sacrilege of (homo)sexualizing a football player, the most important macho figure in Brazil. A teen from the countryside dreams of becoming a member of the national team and with the big help of an older businessman, he manages to make the right connections and achieve his dream.

One of the prizes for this feature film was a grant to produce a second one. For Brasa Adormecida, Batista was offered the screenplay of a pornochanchada, a genre that brought a lot of eroticism to the comedy of manners, usually objectifying women. He rewrote it almost entirely, but kept the main idea of a love triangle between three cousins, two males and one female. Once again, the male body is shot with a kind of awe. At the very end, the groom reveals to the male cousin that he was really in love with him and then they proceed to kiss, witnessed by guests on binoculars. We only see the reaction. In his biography, Limongi Batista says he regrets not having shot the kiss and that all the crew and cast (including Edson Celulari and Paulo César Grande, two well-known hunk actors at the time) asked him to shoot, but he was afraid to be stigmatized, especially during the HIV outbreak, and because unconsciously he tried to take away every sexual representation found in the original screenplay.

This anecdote is a perfect metaphor for Limongi Batista’s career. Such an act of self-censorship is to be found unconsciously for decades in many of his projects. Today, during a boom in Brazilian queer cinema, he remains a very reclusive figure, refusing many spotlights. But he is not without his reasons: throughout his career, he was the target of censorship several times. First of all, a shot in Asa Branca of Edson Celulari naked walking around the moonlight on Estádio Maracaná, the biggest soccer temple in the world, never left the editing table. As he was battling for funds for a new project in the early 80s on Pan, Amor e Fantasia (never made) and old university colleague now in charge of Embrafilme not only refused the film, but asked him if he “wanted to become the gay Brazilian filmmaker”. This story is told on page 144 of his biography compiled by Marcel Nadale, where he bitterly adds: “After Asa Branca, I was ready to fight tooth and nail for this title. But HIV made me retreat completely backwards. I took a very Brazilian attitude: I shut down the floodgate. The opposite of, say, Pedro Almodóvar in Spain, who faced the bull and ran towards it”.

It took him years to reconcile himself and his cinema not only with his sexuality but with the bureaucracy of film production in Brazil. In 1997 he released his third and to-date last feature film, Bocage, an over-the-top homage not only to the Portuguese poet, but to an entire kitsch and baroque cinema. Unfortunately what seemed to be a resurgence after 10 years without a film, turned out to start a longer period of reclusion, which we hope ends soon. Djalma Limgoni Batista’s special and unique voice on Brazilian queer cinema needs to be heard once more.

1. Available in Portuguese at http://repositorio.unicamp.br/handle/REPOSIP/285133?mode=full. Last access on June 30th, 2021.

2. Luciana Correa de Araújo, a leading scholar on Brazilian silent cinema, wrote an article on the film, “Augusto Annibal quer casar!: teatro popular e Hollywood no cinema silencioso brasileiro” for Alceu n.31 (jul/dec 2015). Available on [http://revistaalceu-acervo.com.puc-rio.br/media/alceu%2031%20pp%2062-73.pdf]. Sancler Ebert, a PhD student at Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF), currently undergoes an extensive research on Darwin. Among his writings: EBERT, Sancler. Darwin, o imitador do belo sexo: dos palcos às telas. In: XXI Encontro da Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos de Cinema e Audiovisual, 2018, João Pessoa. Anais do XXI Encontro da Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos de Cinema e Audiovisual, 2018.

3. PhD Thesis, available on [https://repositorio.ufpe.br/handle/123456789/15772]. Last access on June 30th, 2021.

4. Available in Portuguese on [https://repositorio.ufscar.br/handle/ufscar/9909].

5. On that regard, James Green’s book on the history of male homosexuality in 20th century Brazil and João Silvério Trevisan’s large study on same-sex desire and representation in Brazil are still important landmark studies. See: GREEN, James. Além do Carnaval. A homossexualidade masculina no Brasil doséculo XX. São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 2000 [1999]. Translated by Cristina Fino and Cássio Arantes Leite from the original in English; TREVISAN, João Silvério. Devassos no Paraíso (4ª edição, revista e ampliada) - A homossexualidade no Brasil, da colônia à atualidade. São Paulo: Editora Objetiva, 2018

6. Curiously the opening credits of this film references the 12 “Stations of Cross”. But it’s never the homossexual that is compared with the pain experienced by Jesus, but the heterossexual that has his sexuality mistaken.

7. Lacerda has a perfect analysis of the inner homophobia in films that supposedly goes against it in his fourth chapter of his thesis, already mentioned (72-88).

8. NADALE, Marcel. Djalma Limongi Batista: livre pensador. São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo, 2005. This book is basically a first-person account by Limongi Batista organized and introduced by Nadale. All the following quotes from Limongi Batista on this article are taken from this book, unless mentioned it.

9. NADALE, Marcel (pp 39-40).“Ator-fetiche”, literally “fetish-actor”, usually translated as “favorite actor” is a portuguese and french expression designed to term an actor that constantly appears at the director’s films. We have chosen to use the literal translation, as it carries a sexual appeal not translated to the english but is fundamental to Limongi Batista’s filming of Nogueira.