The amateur cinema movement in Vitória, Espírito Santo, during the second half of the 1960s emerged like an explosion. Sudden and surprising, the creation of short films transformed the cultural scene and the imaginary of a timid city that, until then, had not received national attention for its cinematographic production.1

The amateur cinema movement began in January 1965 with the creation2 of the Alvorada Film Society. It gained momentum a few months later with the emergence of another film society at the Modern Art Museum of Espírito Santo (MAM-ES). This was a private museum that had a short existence. We can point to the end of the movement in 1969, when its last short film was produced. This end, which came after such a short period, demonstrates the brevity of the movement. Also, as a cultural explosion, besides being unexpected and fleeting, it left major impressions on the cinema industry: its impact and legacy are reported in the pages of newspapers and magazines of the time, in the works of that revolutionary generation, and later, in the films that solidified, with effort and creativity, a cinema from Espírito Santo.

Influenced by Cinema Novo and by the creation, in Rio de Janeiro, of the JB-Mesbla Brazilian Amateur Film Festival, announced in December 1964 to have its inaugural edition in the middle of the following year,3 The Amateur Film Cycle (called by a local magazine Cinema Novo Capixaba)4 resulted in 11 films shot in 16mm. Three of these works were successful and received national prominence in the JB-Mesbla Festival. More important than the numbers, the cinema movement, simultaneous with other initiatives in the field of arts such as the Vitória Fine Arts Salon (held by the MAM-ES between 1966 and 1968), the creation of the arena theater in 1966 by the group Geração (which shared actors and director with the cinema movement), and music festivals, was able to introduce the idea of modernity and of a politically engaged art in the cultural scene of Espírito Santo.

An overview of the local press coverage at that time reveals both widely favorable and enthusiastic writings by cultural journalists and film critics towards the making of authorial films in Vitória ("Young directors create Capixaba5 cinema")6 and the role of the directors themselves as columnists. Paulo Eduardo Torre wrote for O Diário and for the magazine Capixaba and clearly contributed to the attention given by that magazine to the new generation of amateur cinema. Antonio Carlos Neves and Ramon Alvarado were frequent collaborators of the newspapers A Tribuna and A Gazeta, writing articles with titles such as: “Técnica cinematográfica - A planificação” ["Cinematographic Technique - The Planning"] and “O filme, o autor e o público” ["The Film, the Author and the Public"], both written by Alvarado, and “Da importância do Cine Clube” ["The Importance of the Cine Club"] and “O caminho do cinema novo”7 ["The path of Cinema Novo"], written by Neves, among others.

It was in the Alvorada Film Club that Ramon Alvarado (b: 1946), "a white boy, thin, nervous, and wearing glasses with big lenses",8 the central figure of the amateur cinema movement, and Rubens Freitas Rocha, lawyer, film buff, and owner of a 16mm camera, met in early 1965. From this meeting came the project Indecisão (1965), a film written by Ramon Alvarado and Severino Bezerra with production and photography from Freitas Rocha. The drama has been described by Alvarado as "the social conflict of class struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie through the eyes of a middle-class university student". In the plot, the student is courted and torn between the love of two friends, an auto mechanic and a bourgeois.

Filmed on reversible 16mm film that was bought from a photographic supplies store (the store was also in charge of sending the filmed rolls to be developed in Rio de Janeiro), the production lasted all of 1965, with filming on Sundays, and was concluded only a year and three months later. The locations of the film include a bookstore and a fashionable nightclub. Indecisão was shot on almost all black and white film, with only a single color sequence, the dream of the protagonist. The film was edited by Alvarado with a splicer and a manual moviola. The title cards were created by Roberto Newman, a Spanish artist living in Vitória and creator of the already mentioned MAM-ES, with titles superimposed on the images he painted. Alvarado frequented both Newman's house and the film club created by MAM downtown.

Indecisão became the inaugural film of the amateur cinema movement and was considered to be "the first film made in Espírito Santo” at that time.9 This claim of pioneerism would be reevaluated years later with the rediscovery of Ludovico Persici's cinema (1899-1949). Indecisão subsequently adapted the title of "the first fictional film shot in Vitória". The film premiered in August 1966 at the University Student's Club, before the copy was taken by the director himself to Rio de Janeiro to enter the 2nd JB-Mesbla Brazilian Amateur Film Festival.

Ramon Alvarado would remain the main name in the cinema of Espírito Santo until 1968, when he moved to Rio de Janeiro and entered the professional market as a film technician. He participated directly in nine of the 11 films of the amateur cinema movement and directed four of them: the short fiction films Indecisão (1966) and O Pêndulo (1967), the short documentary O Cristo e o Cristo (1966), and the scientific documentary Cirurgia do Coração no Espírito Santo (1967).

Cirurgia do Coração no Espírito Santo is the only of his films from this period that the research team of the Acervo Capixaba project of Pique-Bandeira Filmes has tracked down, so far. Invited by his brother, physician Luis Alvarado, Ramon recorded two unprecedented surgeries carried out at the Hospital das Clínicas,10 in Vitória. With a running time of five minutes, shot in color on reversible film, and edited by the filmmaker himself, this production shows the eye of a cinematographer in training, as well as Alvarado's interest in technological advances and the progress of science, topics that have always fascinated him.

1. All Those Years

Although Indecisão was rejected by the JB-Mesbla Festival, sitting in the audience at the Clube do Estudante during its first showing was Paulo Eduardo Torre (1947-1995). A native of Rio de Janeiro but living in Vitória to study history, Torre staged two plays by Jean-Paul Sartre with the theater group Equipe, founded in 1966. Influenced by Alvarado’s Indecisão, Paulo Torre would make two short films photographed by Ramon Alvarado: A Queda and Kaput, made between 1966 and 1967, and both of which were submitted to the 3rd JB-Mesbla Brazilian Amateur Film Festival.

A Queda is another lost film. According to Fernando Tatagiba, author of História do Cinema Capixaba,11 A Queda is a 10-minute long silent black and white film that "intends to be an apology for the freedom to be, feel, and think, while at the same time refusing the bourgeois-capitalist society and the commodification of people". Shortly after making the film, the director himself defined it as "my poorly realized cinematographic experience".12 The film's script, a recently found document,13 contains 49 shots and recurring themes in the amateur cinema movement's productions: the dilemma between bourgeois love, represented by an engagement party in a luxurious house, and freedom, staged as the bride's escape to the beach with the one who seems to be her true love, a young bookseller.

In Kaput, the protagonist's dilemma would be different: alienation or engagement? Reflecting on the film in an article published at the time it was made, Paulo Torre said of the main character that "with the discovery of love, he also discovers that the solution is not escape. The solution is struggle, participation" and that the film is stripped down, "without influences from anyone, be it Godard, Bellochio or Penn." The final sequence is powerful: police agents of the political repression assassinate the young militant.

These would be Paulo Torre's only two films, and there is no information about other cinematographic projects that the director wrote or tried to make. He would go on to have a long career as a journalist and would publish two books: Depois do Golpe (1993), a novel set in Rio de Janeiro, where a theater actor who leaves Vitória goes to look for work in television, and Todos estes anos (1994), a book of short stories. In his literary work, drugs and music, especially rock and jazz, are recurrent elements, and the characters move between Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo, between the Military Dictatorship and the period of redemocratization, hippie communities, fashionable bars and artistic environments.

In Depois do Golpe (After the Coup), the narrator reflects: "During his college days, he had been a voracious reader of film reviews in Rio newspapers, which praised Cinema Novo. From a distance, in Vitória, he had been convinced that these were really wonderful films. Years later, however, when he attended some Cinema Novo retrospectives, he came to the conclusion that the reviews (and interviews of the directors) were much better than the films.”

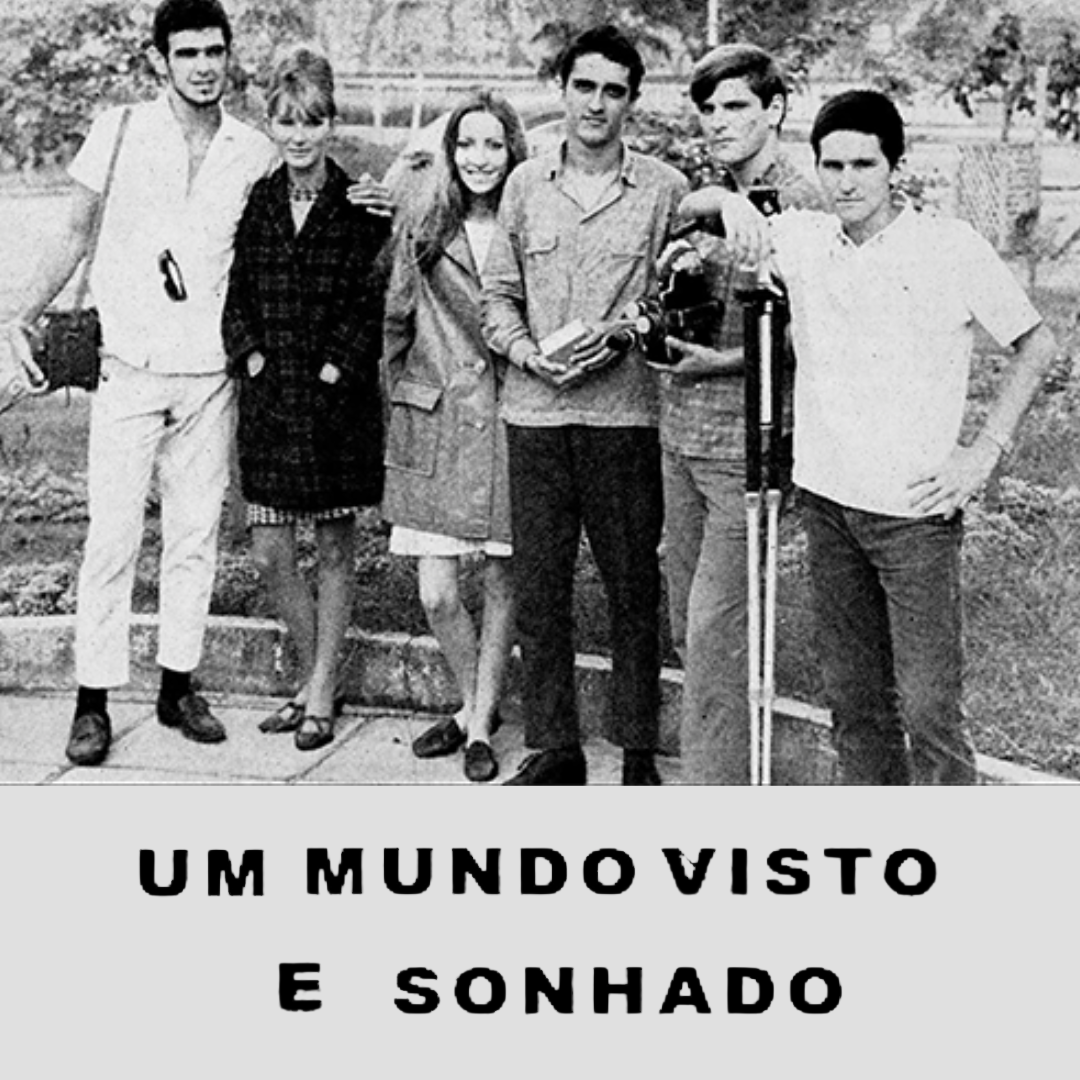

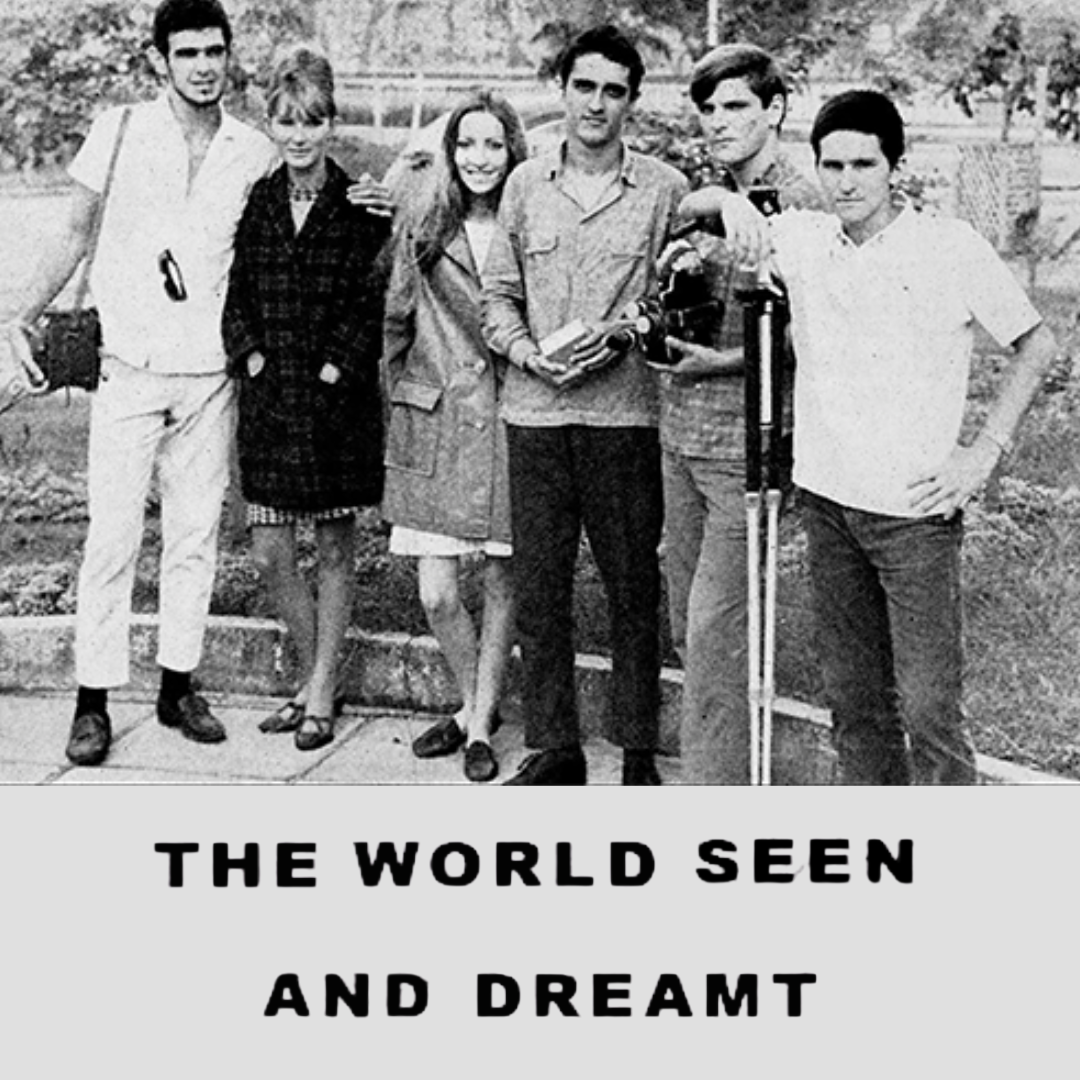

Kaput was restored in 1991 through the initiative of Nenna, a visual artist who was part of the generation of the late 1960s, and Marcos Valério Guimarães, a film club member and film director. Thanks to them, the film survived in magnetic format and I was able to watch it in 2005, projected at the Carlos Gomes Theater, in Vitória, on the tenth anniversary of Paulo Torre's death. Now the film, which was previously restricted to researchers of the cinema produced in Espírito Santo, is finally programmed internationally in the Cinelimite program “The World Seen and Dreamt: A Collection of Films from Espírito Santo”.

2. First Revolt

Like Ramon Alvarado, Antonio Carlos Neves (1944-2007) was a high school student who was linked to the youth wing of the Brazilian Communist Party in the period leading up to the military coup. The most detailed biographical information about him can be found in reports produced by the repressive surveillance sectors of the dictatorial government throughout the 1970s and 1980s.14 Also of value is a talk given by Neves at Rádio Espírito Santo, possibly in 1976, which is preserved in the station's archives.15

Neves left Vitória in 1964 to take the entrance exam for Economics at the University of Brasília. He attended several seminars at the UnB Film School between 1964 and 1965, studying under Jean-Claude Bernardet, Lucilla Bernardet and Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes, among others, until the Dictatorship interrupted the university's original program in October 1965. In 1966, he was working as a cameraman for TV Record in São Paulo.

Upon his return to Vitória that same year, he decided to create with Cláudio Lachini, Zélia Stein, and others, the Grupo Geração (Generation Group) which would go down in history with the staging of Augusto Boal and Gianfrancesco Guarnieri's theatre play Arena Conta Zumbi. Geração’s Arena Theater was a phenomenon and created an unprecedented cultural excitement in the city, leading many people to have to explain their actions to the military.

It was with Geração that Neves met the actor, journalist and cartoonist Milson Henriques (1938-2016). Henriques was the protagonist of Alto a la Agresión, Antonio Carlos Neves' debut short film, shot by Ramon Alvarado, and the first film from Espírito Santo selected for the JB-Mesbla Festival (in the 1967 edition). Before that, Neves would see his filming attempts frustrated: Primeira Revolta, No meio do caminho and Boa sorte, palhaço are scripts that were never made, or material that remained unfinished after some shooting.16

With a running time of 8 minutes, Alto a la Agresión was shot on film negative and had an accompanying soundtrack. The film was assembled on a tabletop moviola in Rio. The director described the film as follows: "…It doesn't tell the life of the boy or of the girl. It captures an instant, like a still frame. We chose the one that fixed some characteristic points of the two characters: she worries about what might happen to her companion - she is just a woman in love who is afraid; he is a militant, his awareness of the problems of his time orient him in another direction. He thinks about Vietnam, Venezuela, the student movements, his country". Unfortunately, this is another film that is considered missing. A frame attributed to the film shows the protagonist in what looks like a torture scene, and from the plot description, we could add it to the list, next to Kaput, of explicitly militant films from the amateur cinema movement.

foi exibido Alto a la Agresión was shown in Vitória on December 3, 1967 at the 1st Capixaba Amateur Film Festival, sponsored by Milson Henriques at the Cine Jandaia. The event, which paid tribute to Alvarado, screened nine productions, among them Automobilismo, a color documentary by Rubens Freitas Rocha and Paladium, a fiction film by Luiz Eduardo Lages. Vitória - Um Belo Dia 1938, a group of vistas of the city Vitória filmed by Luiz Gonzales Batán, Alvarado's father, in the 1930s, completed the session. The festival did not include A Queda, since, according to Fernando Tatagiba, the copy of the film had returned from Rio de Janeiro "with several pieces missing." Information about the 1st Capixaba Amateur Film Festival, the films, the Grupo Geração and the music festivals can be found in old newspaper clippings in Henriques' collection and in texts published by him in the following decades.17

3. An Unimportant Place17

Working towards professional careers was a goal of the amateur cinema generation and moving to Rio or São Paulo was the way to achieve it. In early 1968, Neves would follow the trail of Ramon Alvarado, who was already in Rio. While Ramon sought to integrate himself into the cinematographic environment, Neves joined the Teatro Universitário Carioca (TUCA Rio).

Together, the two capixabas made the film Veia Partida in Rio de Janeiro, an adaptation of a story by writer and film critic Amylton de Almeida, screened as the representative of Guanabara at the 4th JB-Mesbla Brazilian Film Festival (1968). In Jornal do Brasil, José Carlos Avellar evaluated the film as "half lost between an excessive handheld camera movement and close-ups, it has in its favor good photography".19

When Veia Partida was screened and awarded Best Cinematography at the JB-Mesbla festival, Neves was in Europe, where he went on a scholarship to study film, theater and television directing at the Moscow School of Cinematic Arts (VGIK). At VGIK, Neves directed four films: Paula e Tonio, Nós viveremos como vivem os pássaros, A visita do médico (all shorts), and A palavra final de Quincas Berro D´água, a 35mm medium-length film based on Jorge Amado. Ramon Alvarado, invited by Neves to attend a closed screening of these films at the Cinemateca of the MAM-RJ as soon as his friend returned from Moscow, possibly in 1974, still remembers today the great impression made by working with the actors in these Russian-language works. In Moscow, Neves also worked as assistant director on the feature film O mês mais quente (1974) by Yuli Karasik.

When Neves returned to Brazil, he tried to settle in Rio de Janeiro, and write, with William Cobbett, the script for the film O Monstro de Santa Teresa (1975). The filmmaker had a feature film project, Um mundo visto e sonhado (The World Seen and Dreamt), for which he applied for funding through Embrafilme in 1974. At that time, Alvarado introduced Neves to several producers in Rio de Janeiro. Two years later, Neves still hoped to make his first feature film and was waiting for the funds requested from the state company to be released. Although in his statement to Rádio Espírito Santo he referred to the project as an original script, we also found press notes reporting that the filmmaker would shoot a feature film based on the book Vento do Amanhecer em Macambira, by José Condé.20 Perhaps this was the same movie?

What is certain is that Antonio Carlos Neves would never shoot a feature film and would spend the rest of the 1970s dedicated to journalism and especially theater, directing plays (O Inspetor Geral, O Beijo no Asfalto, O Capeta de Caruaru, Alinhavo, and Revolução de Caranguejos) and promoting courses at the Teatro Estúdio in Vitória. In the following decade, he would be hired as director of the Educative TV of Espírito Santo (TVE-ES) where he would produce a children's show (Periquito Maracanã) and multiple innovative series for local television (such as Telecontos Capixabas). Neves would also make several video films: Esta ilha é uma… (1990), Delírios da Mídia, Índios em Questão, Não sou o fogo sou a vida - As esculturas de Neusso Farias (1990) and the project Memória Anos 60 [Memory of the 60s] (1998). Memória Anos 60 has at least two hours of interviews with personalities who were active in the culture and politics of Espírito Santo during the 60s, a historical period in which he himself was a central figure.21

Some of these works are only now being added to the complete filmography of the filmmaker, whose production in film has been inaccessible and his video work poorly known. In the last years of his life, Antonio Carlos Neves dedicated himself primarily to literature. He published the novels Outra vez a esperança (1982), set in Brasilia at the time of the military coup, and Um lugar sem importância (1993), as well as several novels for children and teenagers.

Back to the amateur cinema cycle, still in December 1968, Paulo Torre had written the epitaph of the movement. "Breve história do cinema amador no Espírito Santo" summarized thus the trajectory of that generation of filmmakers: "a brief period of glory, maintained the flame by the enthusiasm of its components, and soon after the best elements go to larger centers". But the "last rebel" came out firing: "For an average person, it is really crazy to give three or four hundred thousand bucks (enough for a few minutes of film) to 'some guys with strange ideas to make strange films, where the country, God and the family are not treated with the usual respect'".22 He closed the article with poetry: "There are no cameras, no film stock. No stages, no nothing. No more rifles or bullets for the last rebels."

But it fell to a young film critic, actor and theater director to direct the last film of the amateur cinema generation. Ponto e Vírgula, by Luiz Tadeu Teixeira (1951), with photography direction by Paulo Torre, was shown at the V Brazilian Amateur Film Festival in 1969, in the edition of the festival that had a theme ("Life") and a length limit for the films entered (90 seconds). Shot on black and white 16mm film, the silent film was added to, years later, with scenes from another project of the director: Variações sobre um tema de Maiakóvski, shot in 1971 and never finished. Years later, an instrumental soundtrack would be added to the film.

Alongside Kaput, restored in the early 1990s, the extended version of Ponto e Vírgula, experimentally telecined in the 2000s, is another film from the Capixaba amateur cinema movement presented in “The World Seen and Dreamt: A Collection of Films from Espírito Santo”.

4. Pendulum

“E sempre serei marginal,

serei nas esquinas o protesto esmagado

sempre a mim será creditada a Vitória."23

Nada/Nada, poem by Carlos Chenier

I met Ramon Alvarado in 2015. He had moved back to Vitória with the desire to shoot a film there again, and we got together for a conversation at Cine Metrópolis, the cinema room I programmed at the Federal University of Espírito Santo. We became good friends, with frequent meetings and conversations at the university and at local film events. I invited him to be an actor in a short film I shot in 2016. In the same year we held a special session at Metrópolis with a DVD screening of his filmography, as Indecisão and his filmmaking career were turning 50 years old. Unfortunately, we did not screen Indecisão, which is considered lost.

It was the numerous conversations and the permanent contact with Ramon Alvarado over the last years that reinforced for me the importance of rediscovering the films of the period and the legacy of the amateur cinema generation. This would be a way to overcome the gap left by the disappearance of most of this filmography and emphasize the importance of the amateur generation for the creation and continuity of the cinematographic practice in Espírito Santo. Alvarado is the precursor and, among all the filmmakers of the period, the one who always worked with cinema and only cinema. He has lasted more than five decades in the industry, even through unstable periods of Brazilian cinema production.

Carlos Chenier's verses, quoted above, convey to me resistance to obliteration. The words close, from a voice off-screen of the poet and actor in the film, the screening of O Pêndulo (1967). Currently, with the same resilience of the poet and the invaluable collaboration of Alvarado, the Acervo Capixaba project is dedicated to researching the filmographies of these pioneers, of which we hope to soon present complete retrospectives to the public.

1. The information contained in this essay is largely based on research done in partnership with researcher Luana Mendonça Cabral for the Acervo Capixaba project, still under development.

2. Ramon Alvarado claims that the Cineclube Alvorada existed sometime in the 1950s and reemerged in 1965. An article in A Gazeta, January 20, 1965, is entitled “Marcelo Osório reabre Cineclube Alvorada” ["Marcelo Osório reopens Cineclube Alvorada"].

3. Foster, Lila. Matizes da cultura jovem: imagens e imaginários em torno do Festival de Cinema Amador JB/Mesbla. In: Revista Estudos Históricos. Rio de Janeiro, vol 34, nº 72, p.30-53, Janeiro-Abril 2021. Disponível em: <http://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/reh/article/view/82090/78953>.Acesso em 13 de Abril de 2021.

4. Revista Capixaba, p.14-17, Agosto de 1967.

5. A Gazeta, Vitória, 2 de julho de 1966.

6. A Gazeta, Vitória, respectivamente 26 de janeiro de 1966, 11 de março de 1967, 1 de janeiro de 1966 e novamente 26 de janeiro de 1966.

7. O Debate, Vitória, 16 a 23 de dezembro de 1968. Texto assinado por Paulo Torre.

8. O Jornal, Rio de Janeiro, 27 de setembro de 1966

9. The newspaper A Gazeta published an article entitled "Cirurgia do coração no Getúlio Vargas" ["Heart surgery at Getúlio Vargas"] on October 3, 1967. The Sanatorium was renamed Hospital das Clínicas (HC) on December 20, 1967, to serve as a training ground when the Medicine course at the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) was created.

10. História do Cinema Capixaba. Fernando Tatagiba. Vitória: Prefeitura Municipal de Vitória, 1988.

11. O Debate, Vitória, 16 a 23 de dezembro de 1968.

12. I thank Yamara Guimarães Torre for her kindness in providing access to Paulo Eduardo Torre's collection.

13. The documents were accessed through Centro de Referência das Lutas Políticas no Brasil [the Reference Center on Political Struggles in Brazil ] (1964-1985): Memórias Reveladas.

14. The Gente Nossa programa Rádio Espírito Santo AM was idealized by Afonso Abreu in 1973. The program with Antonio Carlos Neves' interview is presented by Ester Mazzi.

15. No Meio do Caminho and Boa sorte, palhaço are mentioned by Fernando Tatagiba in História do Cinema Capixaba (1988), while Primeira Revolta is not quoted by the author.

16. The Milson Henriques Fund in the Public Archive of the State of Espírito Santo comprises 27 boxes with different documents referring to the period from 1943 to 2015 and was an important source of research.

17. The title of Antonio Carlos Neves' second novel. An unimportant place. Vitória: Editora Fundação Ceciliano Abel de Almeida, 1993.

18. Jornal do Brasil, p. 10, November 5, 1968.

19. Jornal do Brasil. April 6, 1974

20. The videos were made during the period when Antonio Carlos Neves was at LAUFES - Laboratório de Aprendizagem da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo [the Learning Laboratory of the Federal University of Espírito Santo], which maintains an important collection of productions from the 1980s and 1990s. The year, format, and duration information of each of the cited films is still being collected by the research currently in progress.

21. O Debate, Vitória, 16 a 23 de dezembro de 1968.