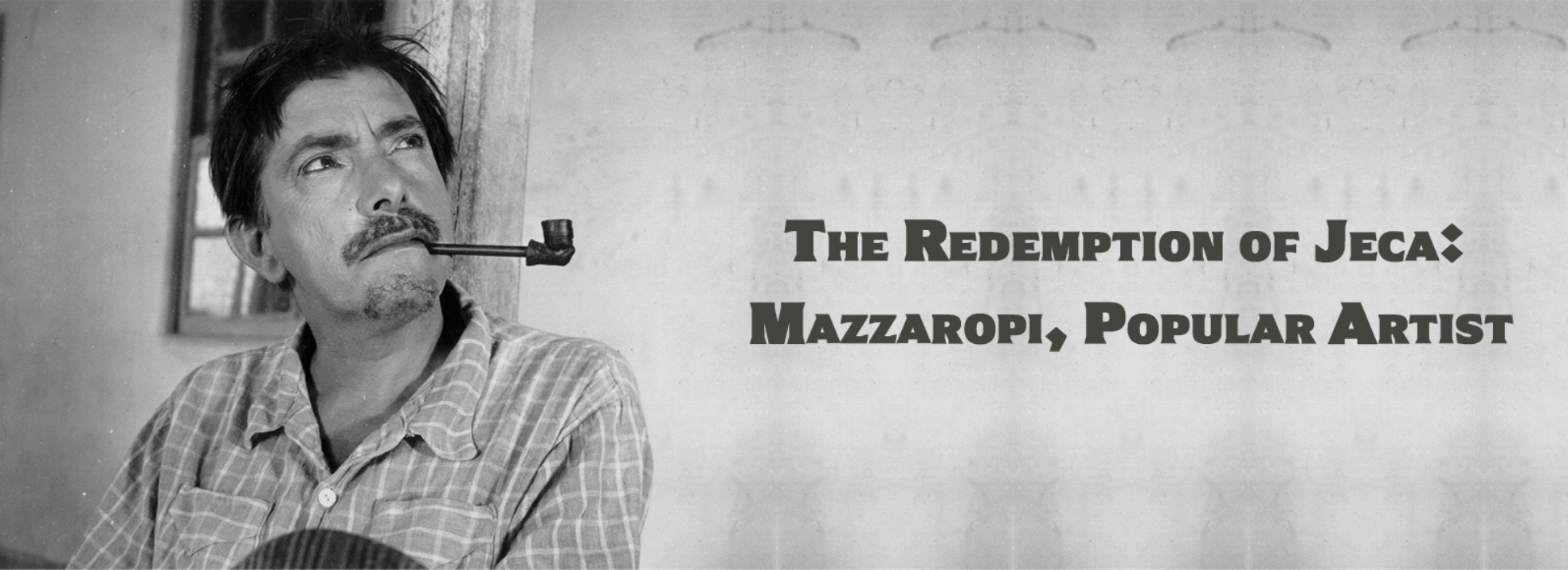

In June 1960, Cinelândia magazine published news about the storming of a movie theater in Taubaté, São Paulo. The reason: without tickets, a crowd of people ran to watch a movie that would be shown in only two sessions. Everyone, between their shoving and elbowing, wanted to see Amácio Mazzaropi's Jeca Tatu.1

The character Jeca Tatu, which originated from the pen of writer Monteiro Lobato (first appearing in Urupês, his debut book, in 1914), soon became the archetypal figure of the caipira in Brazil, a social figure described by literary critic Antonio Candido, in a seminal sociological study, dwelling in the rural landscapes that harbored a way of life and society in the São Paulo countryside.2

A hard drinker and a sickly man, lacking formal education or work, Jeca was an easy prey for powerful landowners, a tool in the system of coronelismo and clientelismo that marked the years of the First Republic in Brazil (1889-1930). Lobato portrayed him as a scourge of the Brazilian social landscape, a specimen who attested to the backwardness and abandonment of the countryside.

The patched clothes and the bare feet, the clumsy walk, followed by a mutt, were also part of the caipira figure that Amácio Mazzaropi had germinated since the 1920s, in the ring of the Circo La Paz, in that same city of Taubaté. This disheveled and burlesque type, which had already been portrayed by the comical figure of radio and film, Genésio Arruda (1898-1967), would have in Mazzaropi a very popular interpreter.

According to Cinelândia Magazine, the film that provoked the storming of Taubaté's theater made 6 million cruzeiros in its opening week in São Paulo alone.3 According to Maria do Rosário Caetano's estimate, Mazzaropi's Jeca Tatu is among the biggest box office records in the history of Brazilian cinema, with approximately 8 million tickets sold.4

At that time, Amácio Mazzaropi already had other films contracted by the newly created TV Excelsior. He was a recurring figure in Brazilian TV, alongside Geny Prado, his longest lasting comical partner. Since his appearance as the driver Isidoro in Sai da Frente (Abílio Pereira de Almeida, 1952), produced by Companhia Vera Cruz, he appeared in almost one film a year. In 1958, he created PAM Filmes and started to take responsibility for the production of his movies. Jeca Tatu would be directed by Milton Amaral, who had already directed Chofer de Praça (1958), the first production of PAM Filmes.

But what place did Mazzaropi occupy in a country such as 1960s Brazil, which dreamed of being modern and thriving? Under the presidency of Juscelino Kubitschek (1955-1960), Brazil was looking at so-called First World countries and discussing its way out of underdevelopment. The agrarian and pre-industrial country would soon be overcome by unstoppable progress, materialized in the development of technology and science.

In government offices and universities, it was believed that two Brazils would coexist: The urban one, powerful and vigorous, owing little to the industrialized countries of the Northern Hemisphere; the other, a rural, archaic Brazil, stuck to semifeudal practices, and to labor exploitation. The "Brazilian Revolution", on the left and right of the ideological spectrum, was debated as a way to break this duality, which relegated the country to being under the shadow of the developed nations.

The arts would soon address the notion of the two irreconcilable Brazils. For Cinema Novo, which was linked to the engaged art of the late 1950s, the man of the sertão - this rural and archaic Brazil - was a raw and massacred person, sometimes tormented by hunger and oppression, sometimes stimulated by a redemptive revolt. In avant-garde production, the first movements of Cinema Novo sought the Marxist new man, whose alienated consciousness had to be overcome to give way to the imagined revolution. The aesthetics of hunger, the refusal of industrial cinema and of everything deemed a deceptive machination of reality - in the anti-colonial spirit that animates the new Latin American cinema at the end of the 1950s - drive a cinema that preferred beaten-down people and rough landscapes.

Dissidence will be another key aspect of Mazzaropi's cinema. His Jeca's manners are also dislocated from the lofty future that the end of the 1950s announced. The lazy indolence of his personality, being disinterested and averse to work, all went against the image of a modern and urban Brazil. The 1950s announced themselves in the optimistic propaganda of Jean Manzon, whose short films were continuously shown before the main sessions in the movie theaters throughout the country. The Brazil of the cities, sustained by conquering the backlands, of which Brasília - the new capital built in the conquered backland - was a symbol, and seemed to aim at a future that did not include the indolent figure of a Jeca Tatu.

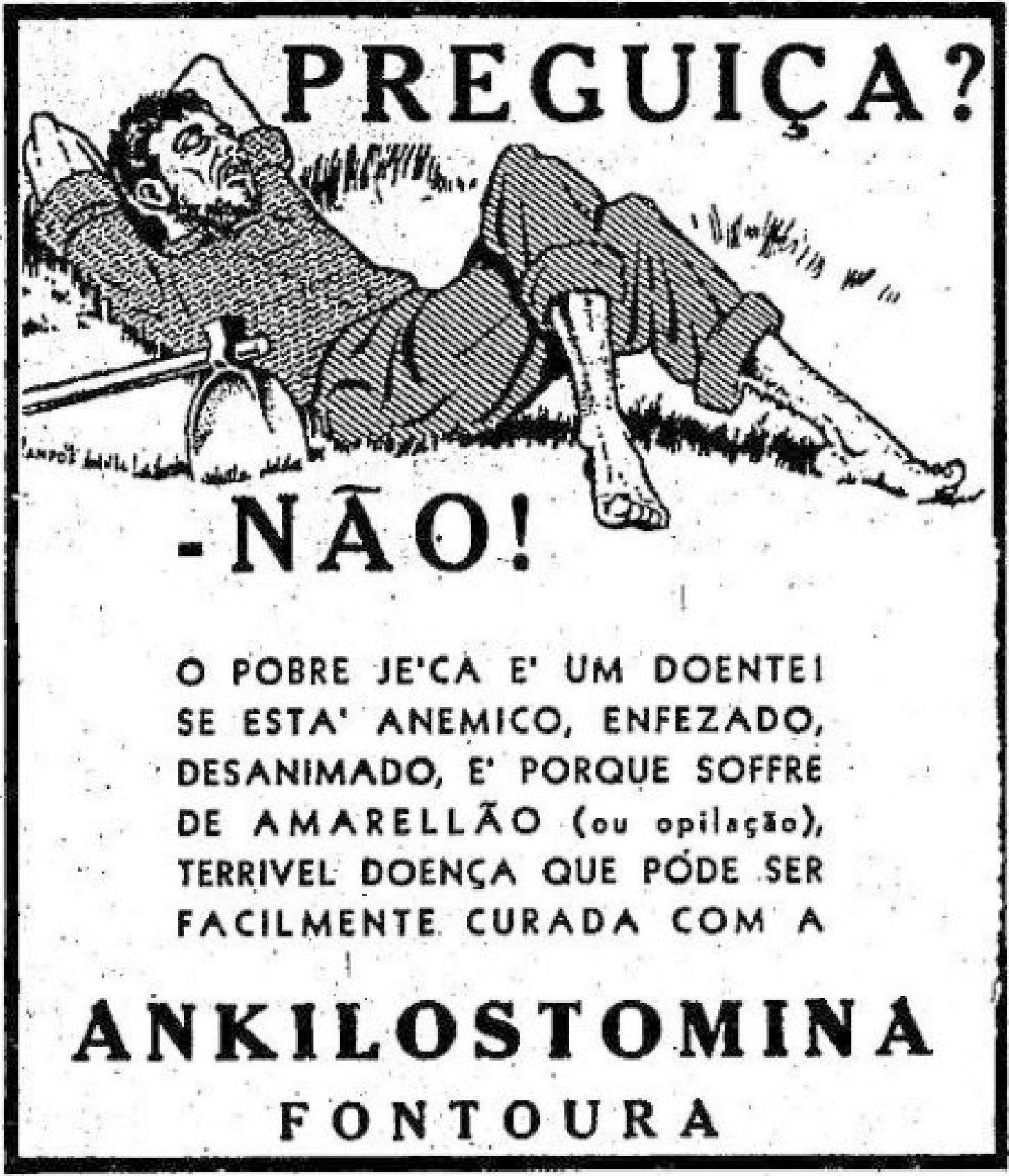

Mazzaropi, however, remade the character that Lobato had invented at the beginning of the century that had then become a sort of symbol of the country man, albeit under a different guise. By then, Lobato’s character, which was a commercial success, was the poster boy for Fontoura Medicamentos, advertising famous vitamin compounds which promised to fight diseases attributed to poor hygiene and poor nutrition.

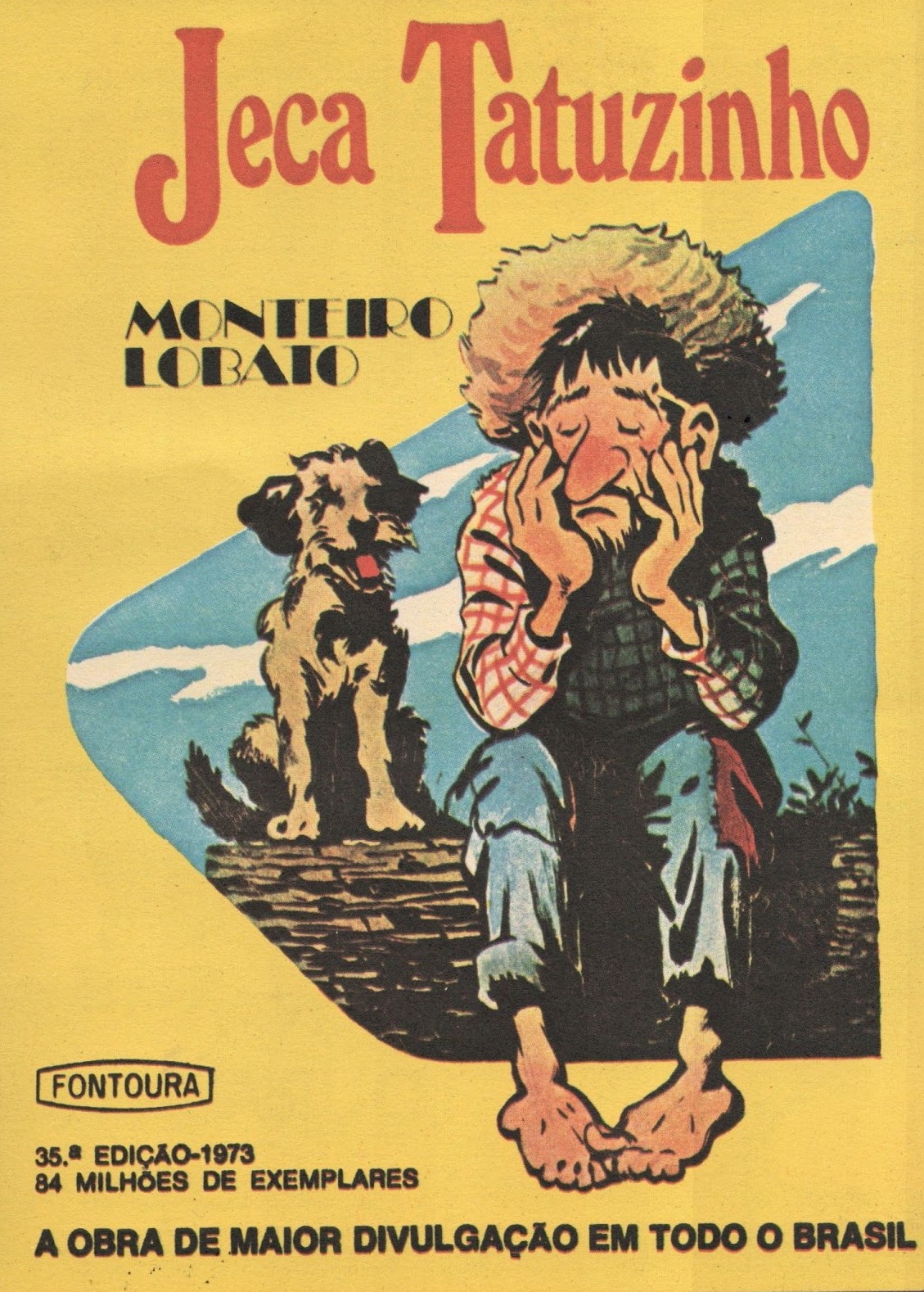

"Jeca Tatu would spend his days squatting, smoking huge straw cigarettes, lacking the willpower to do anything", according to Jeca Tatuzinho magazine, which in 1966 was published with a circulation of 35 million copies for free distribution. But Jeca’s condition was nothing that the compound couldn't cure. "The Biotonic made him handsome, ruddy, and strong as a bull".5

From being a symbol of backwardness and abandonment of the countryside, Jeca - by learning notions of hygiene and taking vitamins from the Fontoura farm - found his redemption, not through revolutionary consciousness, but other more prosaic ones: he himself became a "colonel", rich, successful and loved by his people. The Jeca Tatu of the pharmacy almanac is the antithesis of the rural man dreamed of by the revolutionaries of the 1960s. From this reformulation, Mazzaropi draws his Jeca Tatu, as his film informs us right from the opening text.

Mazzaropi's caipira ways came from observing the customs of the men and women of São Paulo's countryside. His laziness contrasted with a certain romantic naivety. His pranks were only a way to resist the adversities of a hard life. Despite his poverty, he preserved his moral rectitude at any cost. His Jeca Tatu is not the one conceived by Lobato, a sad and decadent symbol of a desolate countryside. Translated by popular comedy and rewritten with commercial overtones, he is a character that Mazzaropi managed to transform into a successful comic model.

Concurrently with the Cinema Novo wave, Mazzaropi's cinema resurrects the formula of the chanchadas, which modern critics wanted to be left behind: slapstick and circus humor, easy jokes, and musical numbers sung by famous radio and theater stars. Mazzaropi mastered all that, as he himself had worked in the circus and radio, where comical characters based on common people were successful before transitioning to the big screen in the 1940s.

Often despised by critics ("an actor applauded by audiences that are not very demanding", Pedro Lima wrote in the newspaper Diário da Noite, in a review of Jeca Tatu),6 Mazzaropi filled the movie theaters of Brazil with a character in double disagreement with the ideas of modernity in vogue in the 1960s - the modernity of machines and cities, on one hand; the modernity of a cinema that vigorously rejected the resources of the chanchada, on the other.

The turmoil of that movie session in Taubaté, and the immense popularity that Mazzaropi would sustain until his death, in 1981, reveal a cinema that is, perhaps, rebellious: when the country imagined the future, Mazzaropi turned to the geography and the people of the countryside; when the critics rejected the easy and cheap humor of the chanchada, Mazzaropi preserved circus-like characters. Against the vogue, Mazzaropi always knew how to be popular.

1. Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro, June 1960, p. 71.

2. Candido, Antonio. Os parceiros do Rio Bonito: estudo sobre o caipira paulista e a transformação dos seus modos de vida. São Paulo: Ouro Sobre Azul, 2017.

3. Aproximately US$ 3 million in actualized values. Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro, Março de 1960, p. 71.

4. Films before the creation of Embrafilme (Empresa Brasileira de Filmes), in 1969, have no official box office data. Caetano, Maria do Rosário. as maiores bilheterias do cinema nacional. Revista de Cinema. Editora Abril, 2002.

5. Jeca Tatuzinho, Instituto Medicamenta Fontoura, 1966.

6. Diário da Noite, Rio de Janeiro, 2 de maio de 1960, p. 29.