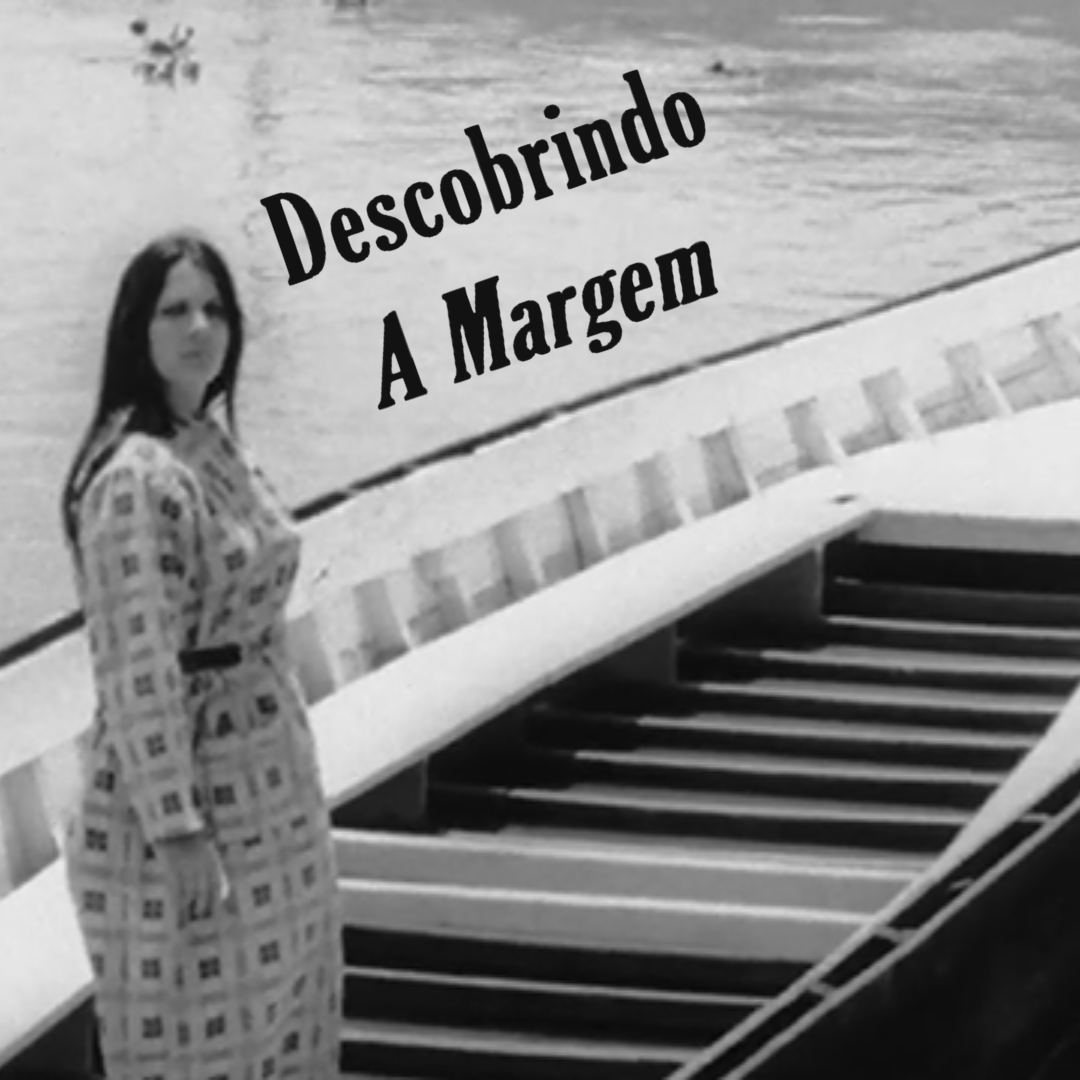

Let's not start by talking about A Margem (1967), it's better to start by just listening. Luiz Chaves' notes, played by his Zimbo Trio, introduce our journey in all its morbid wit (like funeral music playing at a wedding). A boat, sailed by Death herself, crosses the screen after the opening credits, and our heroes face the lens for the first time.

These heroes are crooked figures, deprived in every sense. They’re in a vivid state of trance, like figures on the edge of their own existences who cannot help contemplating their own destiny. They say nothing. They couldn't. After all, they only have to stare at the camera for a few seconds for it to become them, for the camera to be stared at by a different person. Floating between subjective framings, it assaults the eyes of all present, appropriates visions, cages any gaze in order to surround itself by the margins. It is already obvious that no one there can be saved.

Our heroes’ silence is heard from afar. It is there all the time, preventing words from interfering with its empire, imposing in its presence, clear in its voice. That is why we should never confuse silence with contemplation, much less with conformity. On the contrary: it is confrontation. The subjective camera, which transits through other people's eyes, is a collector of opposing perspectives, desperate for some communication that can be conferred within a space established by impossible dialogues. It is ready to possess every body and venture into every angle, until there is no space left unexplored by its kidnapping roots. Consequently, that increases the tensions that already exist in those circles, as it provokes each of the crippled heroes to be willing to expropriate the only possession they have left: their visions. And in that, facing each other is conflict enough for what we have just discovered. If the eye that looks at me soon becomes my own eye, the least I can do is face the one that faces me with some violence.

It is no wonder that Valéria Vidal is the first to open her mouth. Being such a magnetizing onscreen presence, she soon loses patience with the cinematographer who pursues her. The first sentence in the film could not come from the lips of any other character, and it couldn't be any other: "What's up, man? Am I not pleasing you? ”. Unlike the prostitute in Fuller's The Naked Kiss (1964), Valéria doesn't even use high heels to push the lens away from her: she uses her own bare foot.

And we are barely five minutes into the film.

Ozualdo Candeias, a craftsman of the senses, is always working to bring dissonances into conformity. His scenic composition vibrates on the basis of disjunction, of these dissonant elements between the stream, the city, and the country, which end up meeting and missing each other in a continuous flow of clashes. He nails one frame to the other, pushes the boundaries of all the spaces and all the people he has at his disposal, because he is interested in everything besides reality.

Candeias is not content until he operates by confrontation, until our existentially crippled heroes are being appropriated in their entirety to serve a universe of unrealities, of sober intoxication, full of errors, contradictions, paradoxes, inexplicable images, non-existent places, crude poetics... In short, one can say that his cinema moves as a thrust from hell to paradise, proudly balanced in purgatory. The image of the abandoned church returns more than once so we know where we stand.

Being his first feature-length film (which, in itself, is already a tremendous rupture with our world), one might be eager to say that A Margem is a declaration of principles. But perhaps that’s not the right approach. We can't expect such a man to explain himself, to introduce himself. This is not something you do when there is so much to expropriate, to steal for yourself. Candeias doesn't declare anything, he simply steals what he can for his filmic becoming. Therein lies a truth that we can unhesitatingly state: Candeias grows in our eyes in the very first minutes of his first film, for he already demonstrates to be unconcerned with any factor other than appropriation. During this time when Brazilian cinema seeks to debate, without much success, the limits between social fiction and sociological documentary portrayals, it is necessary to remember that Candeias was not only years ahead of this conversation, but has already put an end to it: the camera is a thief of souls, no doubt, and as such it is the most powerful tool for creating universes. Instead of seeking to use it to understand the world, we should see it as an inventor of worlds. It never reproduces, it acts on itself, it steals lines and people, and this imposing, immoral and irresponsible movement is its gesture of invention.

Therefore, let's treat A Margem and Ozualdo Candeias as synonyms. Both stand for immorality, perversion, disrespect for norms and forms (both social and cinematic), and above all, both are agents of investigation of unreality. Candeias and A Margem infiltrate everything they are not supposed to in order to hijack everything that does not belong to them to build their own cosmos of incomprehensible rules and ambiguous limits. We can only discover it once it is projected. Words are lacking, but memories remain of what I saw and heard of this marked clash between figures who already wake up with one foot in the grave. Let's not trouble them with more intrusions, for now.